Can China Avoid a Bad-Loan Financial Crisis?

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Echoes of Japan’s Asset Bubble

China’s exports to the United States have slowed due to mounting trade fiction, and growing uncertainties have caused private fixed-asset investments to falter. China’s economy, however, appears to be bottoming out, thanks to stimulus measures by the Chinese government. Such measures as the lowering of the policy interest rate, the reduction of corporate taxes by 2 trillion yuan (about ¥31 trillion), the easing of the social security burden, the promotion of infrastructure investments through the increase of local government bond issuance, subsidies for high-tech manufacturing industries, and the early commercialization of 5G, the next-generation communication standard, appear to have been successful.

Moreover, there are glimmers of a global recovery of IT demand, and a number of national governments have announced stimulus measures. As a result of these developments, China’s economy is showing signs of bottoming out, as seen in the rebound of new orders for the manufacturing industry.

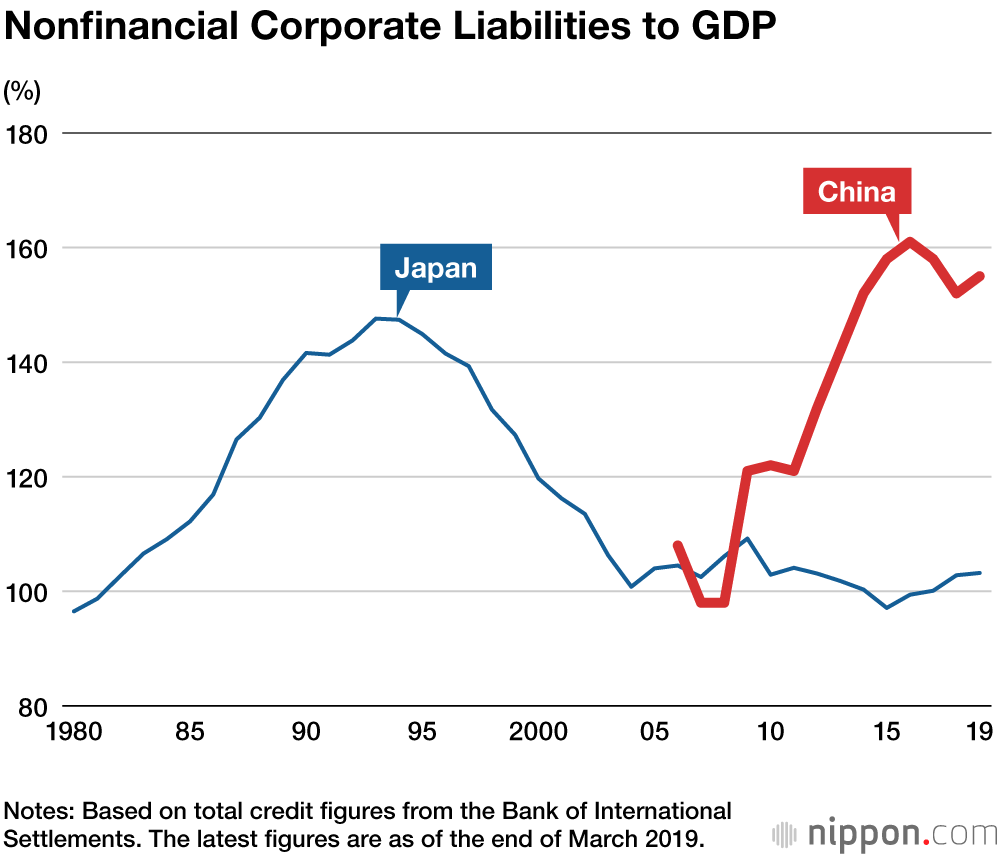

But we must not overlook the structural problems that continue to bedevil China’s economy. While income disparities and environmental pollution are serious issues, I pay the most attention to the problem of excess liabilities and bad loans. In the last decade, liabilities have surged in China, primarily in the corporate sector. According to the Bank for International Settlements, corporate liabilities in China grew fourfold from 31 trillion yuan at 2008 year-end (about ¥480 trillion) to 136 trillion yuan (about ¥2.1 quadrillion) at 2018 year-end. The ratio of corporate liabilities to GDP has surged from 98% to 152% during the same period. As the figure shows, this rapid growth of liabilities is reminiscent of Japan’s asset bubble years.

One third of this 136 trillion yuan consists of loans to special-purpose companies, called local government finance vehicles, that local authorities use to finance infrastructure investments and real estate development. Since the average bank lending rate is currently an annualized 5.7% in China, the annual interest burden of companies is estimated to be 7,752 billion yuan (¥121 trillion), or 8.6% of GDP. Zombie companies with excess production capacity are growing in number, continuing to survive without being forced out of the market. It is worrisome to contemplate how long they can keep borrowing to meet debt payments.

Vastly Understated Official Figures

Given such circumstances, the risk of a financial crisis in China cannot be ruled out. The flip side to the rapid growth of corporate liabilities is the rapid expansion of credit. The ratio of bank lending to GDP has jumped 30% in five years. A report of the International Monetary Fund indicates that the ratio of total credit to GDP has climbed 30% or more in 42 countries over a five-year period. Of those countries, 18 experienced a hard landing and a financial crisis within five years’ time. In other words, more than 40% of countries seeing a credit expansion like China suffered a financial crisis.

To ascertain the risk to China’s financial system, it will be useful to understand the bad-loan situation. In the official statistics of the Chinese government, the bad-loan ratio of all commercial banks rose from 1.0% at 2011 year-end to 1.9% at the end of September 2019. The Chinese government explains that while there is a certain amount of risk, banks have the capacity to absorb losses.

Banks, however, do not always disclose their management situation precisely, and the actual bad loan ratio is thought to be far higher. Using 2015 financial data for some 2,300 listed companies, I have estimated that the potential bad loan ratio is five times the official figure. This would mean that the potential ratio is currently close to 10%. While statistical differences preclude a straightforward comparison, China’s potential bad loan ratio exceeds the peak ratio of 8.4% recorded by Japan’s major banks during the fiscal year ending March 2002. For this reason, we should consider the possibility that over the next few years the failure of small and medium-sized banks will generate mistrust among banking institutions, triggering a China crisis.

One of the reasons for the accumulation of corporate liabilities and bad loans is thought to be the 4 trillion yuan stimulus package and aggressive monetary easing that China instituted in response to the global financial crisis of 2008. Another significant reason is the number of companies and banks making risky business decisions premised by tacit government guarantees or explicit loan guarantees. Since the government protects state-owned companies and banks from bankruptcy, such companies came to assume liabilities exceeding their capacity to repay. State-owned banks also became lax in monitoring their own management and the management of companies receiving their loans.

Much of the funds raised by state-owned companies has been invested in inefficient or marginally profitable infrastructure projects and real estate development. Such manufacturing industries as steel, cement, and solar panels have become burdened with overcapacities. Companies resorting to financial engineering have left them with distorted balance sheets. Investing in risky financial assets over tangible investments is known as abandoning reality for the virtual (脱実向虚, tuo shi xiang xu) in China. While speculative investments do occur in the real estate and stock markets, what has become most popular are bank wealth management products and other shadow banking products that are unregulated by the government and that offer high yields.

Can a Financial Crisis Be Avoided?

Should the problem of excess liabilities and bad loans trigger a financial crisis in China, its effects will propagate instantly like a powerful tremor through the world economy. In 1997 and 1998, a bad loan problem led to a financial crisis in Japan. Financial difficulties spread in a chain reaction between financial institutions, and it became impossible for the government to protect financial institutions through a convoy system where good banks look after those in trouble. It also became unrealistic for financial institutions to continue to protect closely affiliated companies through a main bank system. As a result, an economic growth rate that had rebounded to 5.1% in 1996 slumped to 1.6% in 1997 and became a negative 2.5% in 1998.

Should China repeat Japan’s mistake, the first to react will be the stock and foreign exchange markets. Japanese stocks will plunge, and the yen will appreciate. Japan’s real economy will also be significantly affected. Japanese automobiles, household electronics, and industrial machinery will be priced out of the Chinese market, and Chinese visitors to Japan will decline sharply. From large to small enterprises and from manufacturing to service industries, Japanese companies will be adversely impacted.

The Chinese government has been dealing proactively with precursors to a financial crisis. In May 2019, the People’s Bank of China took over Baoshang Bank, the first failure of a commercial bank in 21 years. This act prevented mistrust from worsening between banks. However, as indicated in the IMF’s Article IV Staff Country Report published in November 2019, there are many other banks similar to Baoshang Bank that risk going under. Recently, the banker’s acceptances of many smaller institutions are being refused, and a few runs on banks have been seen.

Will China be able to continue its economic growth without encountering a financial crisis? Given the small size of its per capita GDP compared to advanced economies, China has plenty of room to grow. Should such growth expand the size of its economy, this will ease sentiment that bad loans and corporate liabilities are excessive. Also, China’s divergent political system may enable it to rapidly deploy public funds to prevent a worsening of the situation. The fact that financial intermediation mainly takes place through state-owned banks is an advantage China has over other countries.

Disposal of Bad Loans Under the Xi Administration

The research of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff of Howard University, however, casts doubt on such optimism. In This Time Is Different, Reinhart and Rogoff note that 268 crises occurred in 66 countries between 1800 and 2000 and that financial crises affected countries at all stages of development. China has many forms of financial institutions, such as commercial banks, the Postal Savings Bank of China, rural cooperative banks, and rural credit cooperatives, that number about 4,000 in total. There are questions about how well the Chinese government understands the bad loan situation at these banks and whether it will be able to allocate sufficient public funds in a crunch.

There is no effective and easy prescription for reducing excess liabilities and bad loans. While the Chinese government is seeking to strengthen the risk management of companies, local governments, and financial institutions, such efforts merely treat the symptoms. They will not solve the problem in any fundamental way. What is required is to gradually eliminate tacit government guarantees and explicit loan guarantees toward banks and companies. Little progress has been made, however, since any misstep in doing so will risk the successive failure of state-owned companies, local governments, and financial institutions.

Since Xi Jinping became president of the People’s Republic of China in 2013, government administration has become more controlling. President Xi intends to maintain an economic structure of codependence through the strengthening and expansion of the state-owned sector. The problem of excess liabilities and bad loans is likely to persist over the long term as a downside risk for the Chinese economy.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Street view of Shanghai. © Pixta.)