China’s Global Infrastructure: Laying the Foundations for a New World Order

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The foundations of globalization and global governance were laid by the modern Western powers through their provision of international public goods. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Britain took the lead in the development of global infrastructure. Later, the United States (with competition from the Soviet Union) took over as the top provider. In the twenty-first century, China has emerged as a rising player in this arena. From a global and historical perspective, this challenge can be viewed as the root of the growing animosity between the United States and China.

International Public Goods and Global Hegemony

In the process of building its vast empire, Britain provided the world with such global public goods as undersea communications cables, the customs and quarantine systems, a financial settlement network centered on the City of London, and the pound sterling as a global currency. Later, the United States assumed the leading role in the provision of infrastructure, including the modern communications cables that provide global Internet connectivity and the satellites that support the Global Positioning System. The West also provided a framework for global governance with the creation of the League of Nations, the United Nations, and other institutions. The provision of such international public goods was a costly investment for the Western powers, but it laid the foundations for their empires (in various senses of the word).

In short, the global infrastructure developed by leading Western powers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries created the basis for today’s international order. And because the West embraced the principles of liberal democracy and the rule of law, such global governance frameworks as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Group of Seven upheld those principles as well. This is why, under the present international system, the world’s public goods are managed in accordance with rules that reflect those same principles.

Today China is challenging the liberal international order on two different fronts, from within and without. On the one hand, it is challenging American leadership of existing international systems, which grew from the public goods provided and maintained by the West. On the other hand, I would argue, it is attempting to build a separate global infrastructure of its own as the basis for a new world order.

China as Free Rider

For many years, China reaped the benefits of membership in the international order without paying its dues. From the 1980s on, it took full advantage of the world trade system to power its own economic growth and development while evading many of the rules and obligations imposed by that system. It did so, for the most part, not by openly opposing the established international order but by refusing to enter into frameworks that it considered disadvantageous or by seeking special dispensations in consideration of the nation’s unique history and circumstances. In this sense, China was more or less a free rider in the international order. However, blame for such behavior lies in large part with the Western industrial nations that tolerated it. At the heart of this tolerance was Washington’s strategy of “positive engagement”: essentially, a policy of smoothing the way for China’s painless entry into global society in the expectation that it would eventually be fully integrated into the Western political and economic order.

China betrayed those expectations, however, even as it developed into the world’s second largest economic power and third largest military power. By 2016, under President Xi Jinping, Beijing was openly rejecting Western values, denouncing US-centered security arrangements, and offering to spearhead the creation of a new world order. At the nineteenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China in the autumn of 2017, Xi Jinping expounded on his vision of a new Chinese-style world order based not on Western liberal democratic values but on “win-win” economic relationships. The Belt and Road Initiative was seen as a testing ground for that new order.

China’s Emerging Global Infrastructure

As stated earlier, China is challenging the US-dominated international order on two fronts. One is through its increasingly vocal and influential role as a member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, and other established frameworks for global governance. But a more serious challenge is that posed by China as an alternative provider of international public goods. By building its own global networks, China hopes to gradually wean the world from dependence on the international public goods provided by the United States and its allies in the advanced industrial world.

Much has been written about China’s overseas infrastructure investment under the Belt and Road Initiative and its involvement in 5G wireless networks. Here I would like to examine two other key infrastructure development initiatives.

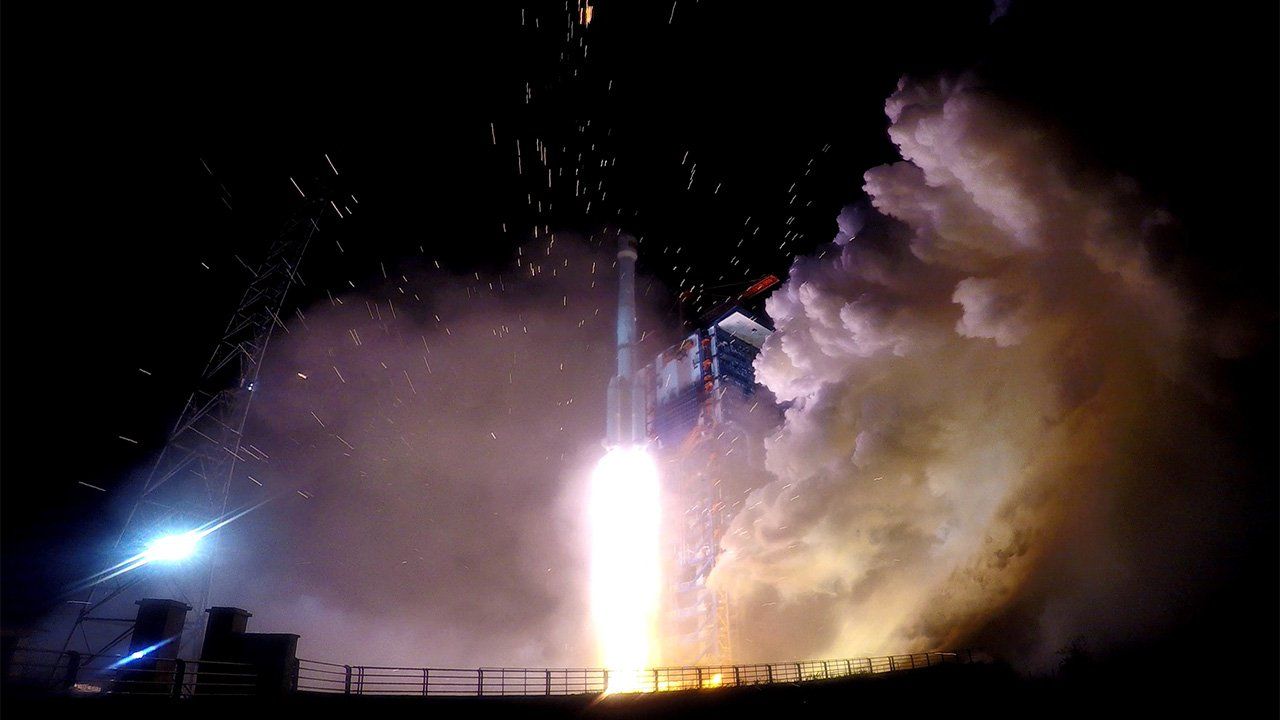

One is the BeiDou Navigation Satellite system, or BDS. Begun under the regime of Jiang Zemin, this satellite navigation system—China’s own GPS—commenced commercial operations in 2012. Since December 2018 it has been offering services to customers worldwide. Work on the program has continued apace, even amid the coronavirus outbreak; on March 9, 2020, China launched its fifty-fourth BeiDou satellite from Xichang Satellite Launch Center. This gives China a satellite network rivalling that of all the Western nations combined and the largest number of satellites in the skies over East Asia, including Japan. According to the proceedings of the China Satellite Navigation Conference of June 2019, some 70% of all mobile phones in China are already using BeiDou. At the same time, Chinese-made BDS-compatible mobile devices are spreading around the world.

Undersea communications cables are another key focus of Chinese investment in global infrastructure. Today’s global communications network began to take shape in the nineteenth century, when Britain took the lead in connecting countries and continents via submarine telegraph cables. Today’s modern transoceanic fiber-optic network, which transfers a mind-boggling volume of data around the world, is the fruit of decades of innovation and investment by the United States and other Western nations.

In recent years, China has dramatically stepped up its investment in the construction of submarine cables. A prime example is AAE-1, a vast cable network linking Asia, Africa, and Europe, spearheaded by China Unicom. In 2017, Huawei Marine, a subsidiary of Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei, began work on an undersea cable linking Africa and South America. Chinese firms have also partnered with Japanese international carrier KDDI and Google, among others, to build the transpacific FASTER cable system linking Japan and the United States.

Dovetailing with this infrastructure-building program is the growing success of Chinese mobile devices in the global marketplace. Huawei now ranks third in world market share— after Samsung and Apple—followed by Chinese vendors Xiaomi and Oppo. The Chinese devices come equipped with links to China’s information infrastructure, including BeiDou, and they offer the advantage of compatibility with the 5G networks that will support the next generation in mobile computing and communications.

Confronting the Threat

Washington and other Western governments have begun to view China’s network-building activities as a threat. Washington has repeatedly sounded the alarm over Chinese involvement in other countries’ 5G networks, and the US Department of Justice has set up a panel to assess national security issues relating to foreign ownership in the telecommunications sector. After scrutinizing an application by Facebook and Google to use the transpacific Pacific Light Cable Network, a high-speed undersea cable network built in partnership with a leading Chinese telecom firm, the Justice Department finally granted conditional approval for Google’s use of a portion of the network, excluding Hong Kong. In 2018, the Australian government took charge of a project to build a submarine communications cable network linking Sidney, the Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea after persuading the Solomon Islands to drop a contract with Huawei over security concerns.

From a national security standpoint, Washington, Canberra, and other governments worry that Beijing could use infrastructure built or operated by Chinese entities for the purpose of cyber-espionage or cyberwarfare, or that it could block monitoring by other governments. More fundamentally, China’s role in global connectivity is seen as problematical because of the way the Chinese operate their own networks, subordinating individual rights to “national safety,” broadly defined. There are also concerns about the linkage of mobile devices with the Alipay network and the use of China’s digital currency, which could undermine the bank-based system of overseas remittances and the role of the dollar as the key currency in international transactions.

China has invested disproportionately in state-supported projects to boost its status as a provider of international public goods. Moreover, it seems clear that the government intends to continue channeling vast resources into these projects even as it grapples with the economic impact of COVID-19. Far from being chastened by the coronavirus pandemic, Beijing is boldly leveraging its experience with the virus to boost its standing as a provider of public goods, touting the efficacy of its countermeasures and proffering various forms of assistance to other countries. How far such efforts go in furthering Beijing’s ambitions of exporting the “Chinese model” and laying the foundation for a new world order remains to be seen.

(Originally Published in Japanese. Banner photo: A rocket carrying two satellites for the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, China’s answer to the Global Positioning System, lifts off from Xichang Satellite Launch Center on November 19, 2018. © Xinhua/Aflo.)