Rough Sailing Ahead for China in the Post-COVID-19 World?

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Economic Downturn Undermines Xi’s Legitimacy

Since China’s political leaders are not chosen in elections, there is no way to prove an administration’s legitimacy. The only thing that underpins it is continued economic growth and satisfaction for the people. This is why, 40 years ago, Deng Xiaoping repeatedly stated that there was “no argument greater than growth.” This suggests that if the economy stalls, the Chinese Communist Party might not be able to remain in power.

The Xi administration officially came to power in March 2013. Economic growth that year was at 7.76% year on year; in 2014 it was 7.31%, in 2015 6.92%, in 2016 6.70%, in 2017 6.80%, in 2018 6.60%, and in 2019 6.10%, indicating a gradual decline. In particular, the COVID-19 crisis led to an unprecedented slump in the first quarter of 2020, with economic figures down 6.8% from the year before. In the face of this unexpected crisis, there is now a possibility that the Xi administration may not be able to secure a third five-year term from 2023.

In addition to the internal structural causes for the slowdown in China’s economic growth, exports have been adversely affected by the trade friction between the United States and China. In addition, supply chains have been fragmented due to COVID-19, and with the bankruptcies among smaller Chinese companies, employment figures have worsened and the domestic market has weakened.

This article will take into consideration these major problems as it looks ahead to China’s politics, diplomatic relations, and economic potential after COVID-19.

An Uncertain Political Situation

Whatever the age, autocratic governments are cloaked in secrecy, and it is difficult to tell what is going on inside. In 1991, the Soviet government that had seemed so unshakable collapsed as though suddenly hit by an avalanche, without external pressure like an invasion by another country. No international political analyst had been able to foresee this. There is nowhere near enough material to use the analogy of the collapse of the Soviet Union to say that modern-day China will collapse. However, there is no denying the accumulation of problems in Chinese society.

Over the past seven years, the Xi administration has purged 2.5 million corrupt officials. The purging has garnered wide support from the people, but if the current corruption among Communist officials cannot be eradicated, the party will lose the support of the people. The Xi administration is strengthening the system of surveillance which encompasses everyone, from high-level CCP officials to people at grassroots levels. It is gradually building in China a strict surveillance system reminiscent of what was depicted in George Orwell’s novel, 1984.

However, it will not be easy to implement the Xi administration’s political ideal, which deprives the people of their freedom. The reason for this lies in the fact that, for the past 40 years, the people of China have gotten a taste of the delights of freedom. It is highly likely that there will be immeasurably fierce opposition to having that freedom taken away, and it is possible that its magnitude will topple the Xi administration. There is no way that a society that is not free can be a happy society.

In the Chinese classic by Xunzi, there is a teaching that “A ruler is like a boat and common people are like water.” This means that water can make a boat float, but a boat can also be capsized by that same water. The nobleman who cannot ensure the happiness of his people will eventually be overthrown by them. This teaching indicates that the Xi administration is facing a threat to its survival.

The Whole World as an Enemy

In advocating to the people the restoration of the nation as a great power, the Xi administration has been executing its “Belt and Road Initiative” as a major project that would make China into a world leader. On its face, the international strategy of the Xi administration is to move away from the existing system that solely benefits developed countries, reshaping it into something new that would be more equitable towards newly developing countries.

This awareness of the problem is not in itself wrong, but one must remain conscious that, until a new set of rules has been put in place, it is necessary to obey existing rules. With the advent of the Xi administration, there has been a constant challenging of existing international rules without waiting for changes in them. Among these is the issue of sovereignty over territorial waters. The original historical background to these issues can be complicated and, in many cases, it is impossible to decide easily on white or black. That is why it is customary to request the arbitration of an international court.

A large country, China has borders with 12 other countries. Quite a few of these, like Japan and South Korea, are maritime states. In the past, during the time of Mao Zedong, China engaged in severe border disputes with the Soviet Union. More recently, as Beijing has consolidated its economic power, it has moved from land to sea expansion. Furthermore, rather than negotiating, it seems to be giving precedence to creating “facts on the ground.” The instability in the East Asia region that this approach engenders, though, is increasingly an inconvenience for China itself.

The Chinese government has long positioned the Taiwan issue as a core interest for the nation, and has consistently refused to take the option of using military force to secure unification off the table. In Hong Kong, meanwhile, Beijing has been making concrete moves toward what is effectively “one country, one system,” backtracking from promises made when the territory reverted to China from British rule, through actions such as enacting the new national security law. The problem is that once the popular mindset in places like Hong Kong and Taiwan has moved away from China, even if Beijing does achieve unification with Taiwan and strengthen its control over Hong Kong, the distance that separates their people from the central Chinese government means there will be little benefit for the latter.

As a result of the COVID-19 threat, the relationship with the United States, which had already been shaky, has deteriorated further. China has implemented economic sanctions against Australia for stating that there should be an investigation into the source of the virus outbreak. Such behavior will eventually lead to a backlash from international society. Some political analysts are predicting the advent of a new cold war between the United States and China. Whether such predictions come to pass or not, the decoupling of the United States from China seems likely.

The Economic Outlook

The Chinese economy is facing the kind of downturn it has never experienced before. At the National People’s Congress held on May 22, Premier Li Keqiang delivered the government work report but, in an unprecedented move, did not give an economic growth target for this year. Rather, to state the facts correctly, he was unable to give a target. On the other hand, he placed great emphasis on employment, referring 39 times to maintaining stability in the job market.

Much of the sharp downturn in China’s economy is due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but exports have at the same time been hampered by trade friction with the United States, another factor weakening demand from overseas. Looking at domestic demand in the short term, the ratio of household savings to disposable income stands at 30%, making it a major element underpinning an economic recovery. However, with the deterioration in the employment situation, one cannot expect a V-shaped rebound. A key reason for this is that, unlike Japan, China does not have a credit guarantee system for small and medium enterprises, and so private companies cannot borrow money from state-owned banks. This, too, is underpinning the sharp rise in the unemployment rate.

At present, the Chinese government is making efforts to encourage direct investment by foreign corporations in China. However, many multinationals and other corporate actors appear to be shifting export-oriented manufacturing facilities from China to countries such as Vietnam. They probably will not move manufacturing facilities for products meant for sale in China out of the market, but with the restructuring of global supply chains, China’s position as “manufacturer to the world” may be seriously compromised.

Lastly, I would like to touch on Sino-Japanese relations. In order to overcome the deterioration of its relationship with the United States, China is working to improve its relationship with Japan. President Xi was supposed to make his first ever state visit to Japan in early April 2020, but this was postponed due to COVID-19. In principle, a visit by year end is still a possibility should the rate of infection abate, but with the situation in Hong Kong and the further deterioration of US-China relations, a visit this year is looking increasingly difficult.

At this stage, a rapid deterioration in Sino-Japanese relations seems unlikely, but it is conceivable that the global environment surrounding China will grow increasingly unstable and the geopolitical risk in East Asia will increase further. For the international community, and for East Asian countries in particular, it will become increasingly important to properly manage the China risk element.

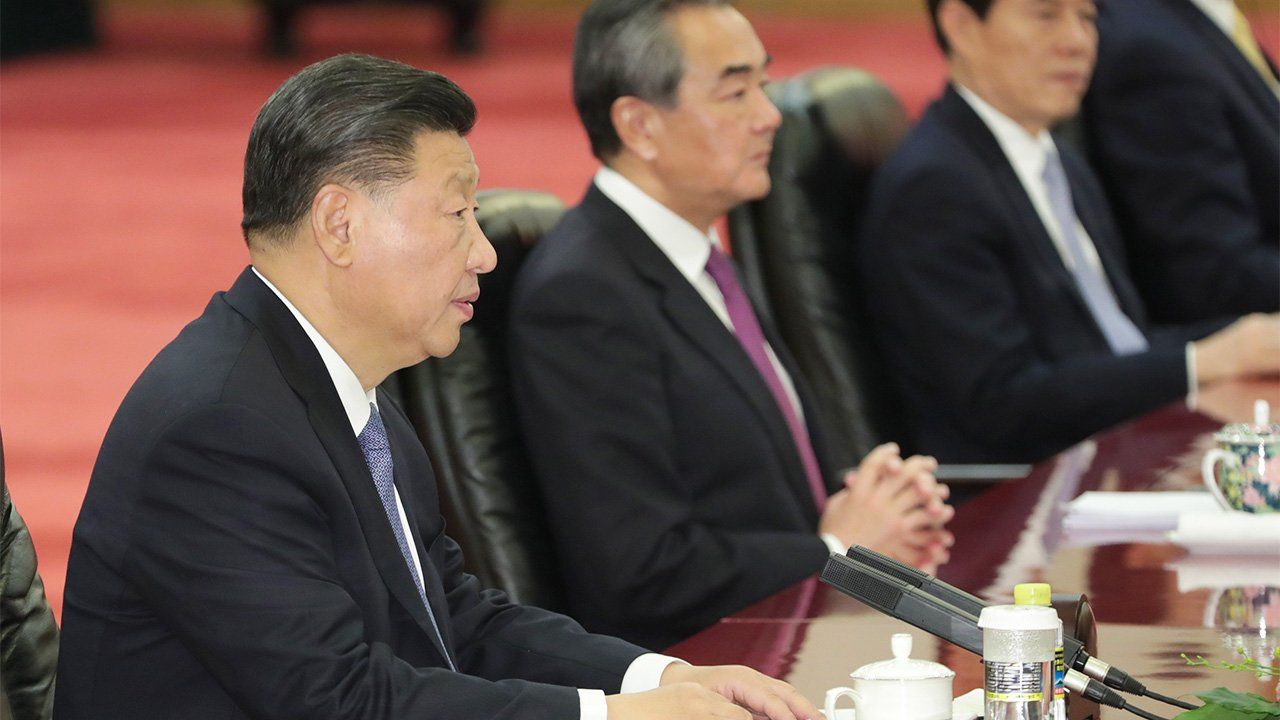

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: People’s Republic of China President Xi Jinping, at left, attending a Japan-China summit meeting. © Jiji.)