Bringing the Second COVID-19 Wave Under Control

Health Society Lifestyle Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Where Japan Stands

INTERVIEWER Tokyo and Osaka are seeing record numbers of coronavirus cases. What is your take on the current situation?

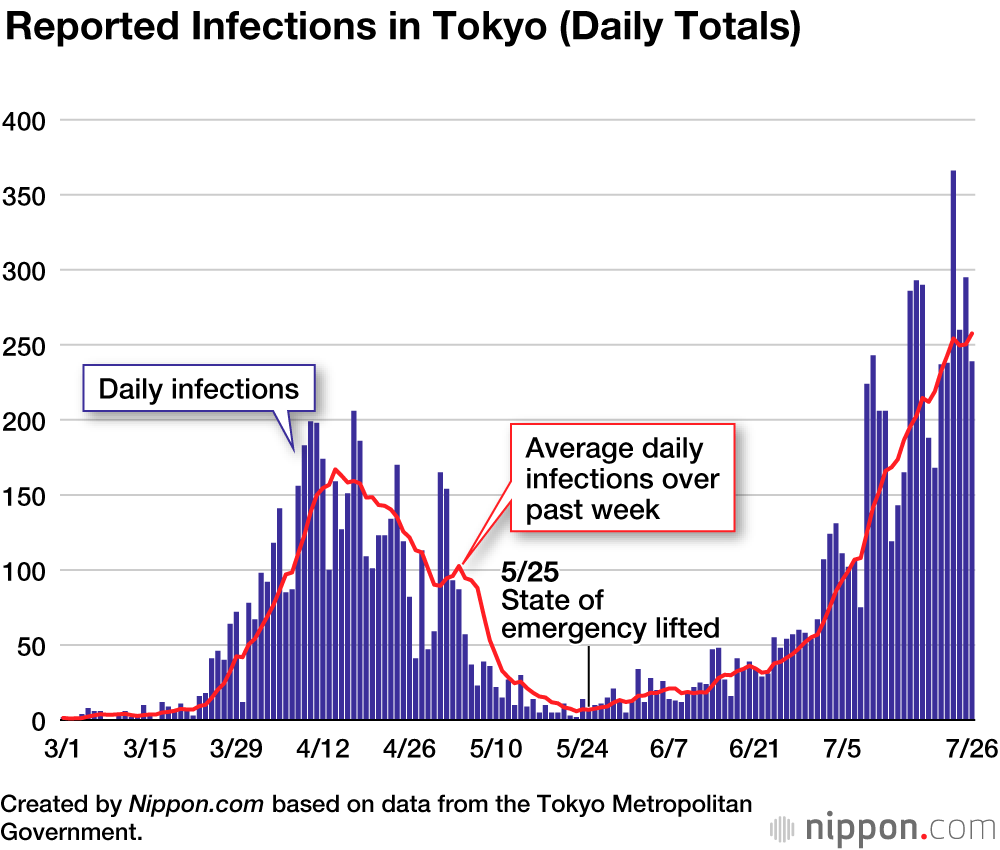

MIYASAKA MASAYUKI There’s no question that we are seeing an uptick in cases. Without knowing the type of virus involved, we can refer to the current outbreak as either a continuation of the first wave, or the beginning of the second wave. The increase in infections has been concentrated in specific entertainment districts, including Tokyo’s Shinjuku and Ikebukuro and Osaka’s Minami, along with their surroundings. These areas harbored a very high number of COVID-19 carriers, and people who frequented these areas have unwittingly taken the virus back to their homes and workplaces, causing it to spread steadily through their communities.

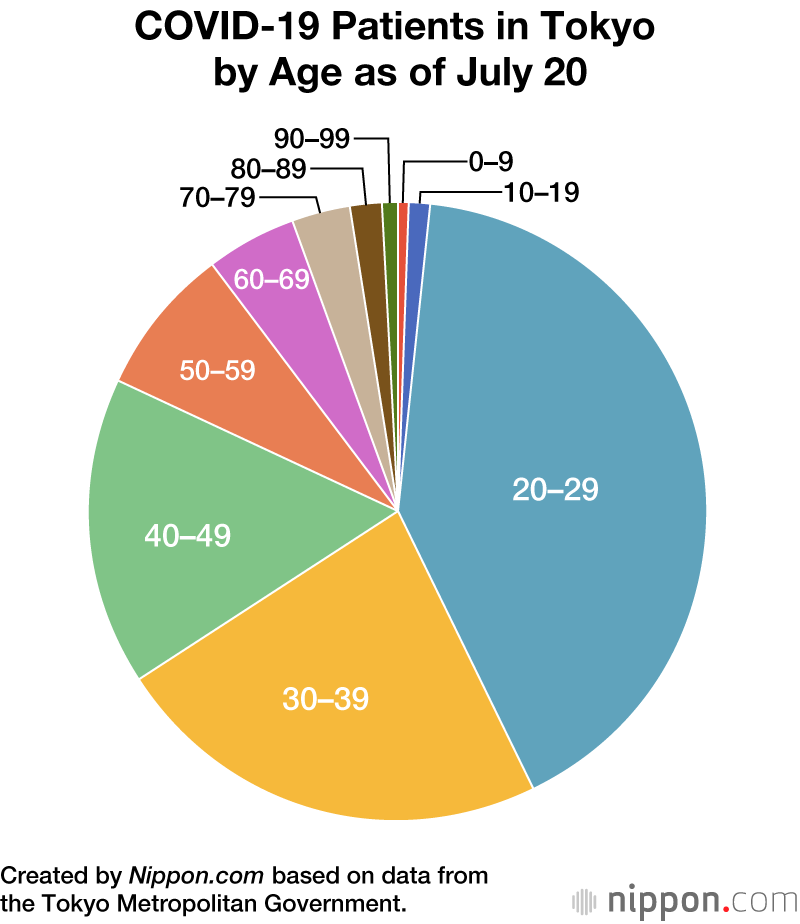

The current spike in infections is by no means restricted to a small geographical area, either—we’re beginning to see outbreaks in surrounding areas as well. And it’s only a matter of time before this outbreak will no longer restricted to young people. While I thought people had learned the lessons of the first wave of infection, some have not, and continue to frequent entertainment districts. That is the problem.

INTERVIEWER We were told the second wave would not arrive until autumn or winter. It appears to have hit much earlier than expected.

MIYASAKA Those estimates were merely individual opinions. A lot of people thought the virus’s vulnerability to heat and UV light would keep it at bay in summer, so the second wave would not hit until autumn. While many believed this theory, in the United States we have seen significant outbreaks in summer, in places like Florida.

INTERVIEWER How is the current outbreak different from the first wave?

MIYASAKA The circumstances are different this time. The received wisdom, which invoked the concept of herd immunity, held that when a virus-naïve population is exposed to a novel virus, a given percentage of individuals will contract it. Nishiura Hiroshi from Hokkaidō University said that as none of us has immunity to COVID-19, up to 60 percent of the population in Japan could contract the virus. I disagree with his assessment, however.

Immunity levels vary significantly amongst the population, meaning that those with compromised immune systems will contract COVID-19 before their healthier counterparts. The chances of becoming infected after exposure to a given amount of virus are not the same for everyone—those with a high resistance to infection will remain uninfected, eventually halting the spread of infection. Another factor is the public’s knowledge about the virus. During an outbreak, people will maintain social distancing. The theoretical statement that every individual infected goes onto infect 2.5 others assumes no preventative measures are taken—if the population observes social distancing, infections will stop. R0—the basic reproduction number, pronounced “R-nought” or “R-zero”—is actually around 1.25 in Osaka, meaning that if just 20 percent of the population develops immunity, the spread of the virus will be stopped. R0 is approaching 1.25 in Tokyo as well. In other words, we are approaching a state in which the virus is no longer spreading.

Antibodies Are Not Everything

INTERVIEWER Can you briefly explain how immunity works?

MIYASAKA People talk as if immunity is all about antibodies. There is a theory that the spread of COVID-19 will be stopped when 60% of the population develops immunity. However, this assumes that antibodies are the only things capable of conferring immunity. In fact, exposure to a given amount of COVID-19 will never result in 60 percent of a population becoming infected. Even in Wuhan, the percentage of the population that contracted the virus was no more than 20 percent.

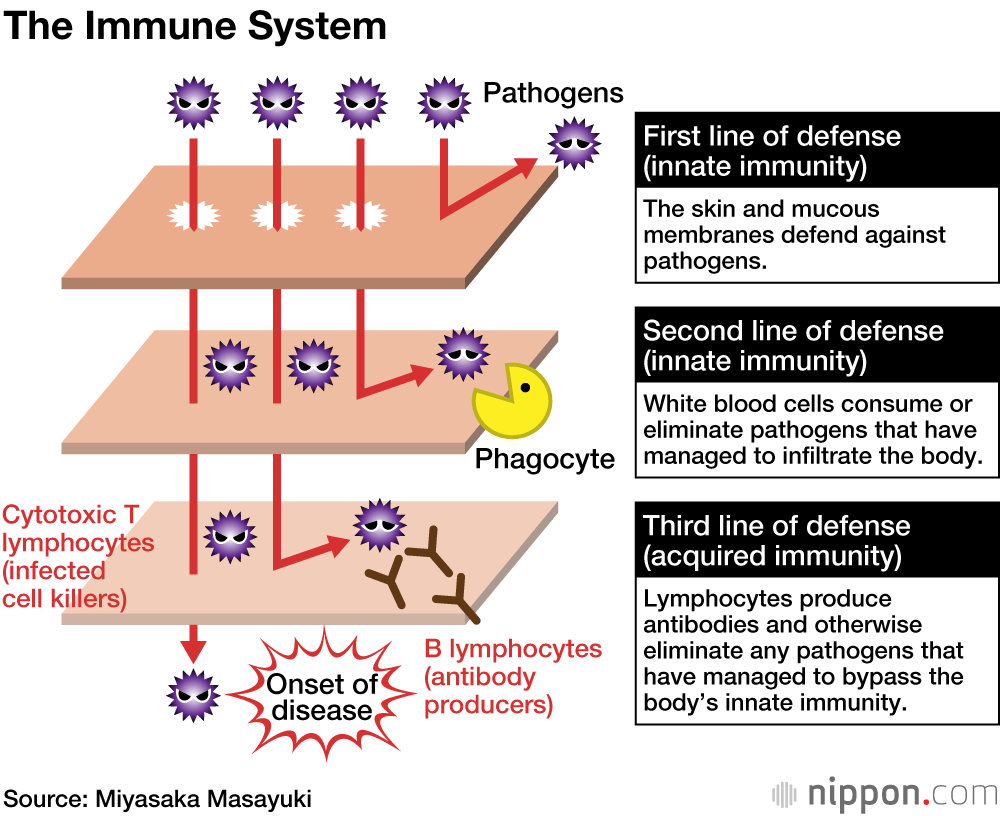

The human immune system is comprised of two layers. The first line of defense is our innate immunity—think of soldiers guarding a gate—which attempts to repel all invaders. If our innate immunity is compromised, our acquired immunity kicks in in the form of lymphocytes. T helper cells, which perform the role of controllers, respond to the infection by instructing B lymphocytes to produce antibodies, which in turn attack the virus. The other avenue of defense involves helper cells creating cytotoxic T lymphocytes, or “killers,” that completely destroy infected cells. While antibodies are only able to kill viruses outside cells, these killer lymphocytes are able to kill viruses inside cells. You need both antibodies and killer lymphocytes to reliably defeat a virus.

INTERVIEWER So it isn’t just the antibodies—the “soldiers at the gate” are also important.

MIYASAKA People ignore the fact that some people are able to shake a virus they don’t have antibodies for with their natural immunity alone. Antibody seroprevalence is not the same as the infection rate. In other words, if your innate immunity is robust, you don’t have much to worry about.

It’s likely that the antibodies our bodies make in response to COVID-19 infection will only last for around six months. If this is indeed the case, it will be impossible to attain herd immunity. However, immunity is a two-pronged defense: Some individuals are able to defeat the virus using their innate immunity alone. People shouldn’t get too hung up on antibody seroprevalence rates.

The Risk of an Exponential Spike

INTERVIEWER Cases are currently on the rise. Do you think the increase can be halted, or could we see a runaway number of cases?

MIYASAKA While the true number of infections is definitely higher than the number of positive PCR results, I believe the rate of infection will eventually dwindle. That is, we will not see an exponential increase in cases. During the initial wave of infection, we were able to stop the virus from spreading further by restricting our movements by 65 percent. As long as people maintain social distancing, avoid the three Cs, namely closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings, and impose reasonable restrictions on their behavior, we will definitely be able to slow down the spread of the virus. However, if there is not enough testing, we get undetected clusters of infection, and the virus spreads rapidly through the community, as has been the case in Western nations, the epidemic will know no end. Fortunately, the prevalence of the virus in Japan is far lower than in the West.

INTERVIEWER And yet levels of infection are now higher than the initial peak.

MIYASAKA The statistics seem worrying if you only focus on the number of infections, but Japan’s prevalence of infection and morbidity rates are far lower than in Western nations. It should be noted, however, that the prediction that the second wave of infection would be only minor has proved to be untrue. While it initially looked like we had defeated the epidemic, this was only the picture on the surface. In reality, there were clusters of infection in Shinjuku, Ikebukuro, and Minami that we didn’t know about. These combined with community contact to create the second wave. By testing exhaustively and reducing cases in these areas, potential causes of infection can be reduced.

What We Should Do

INTERVIEWER Budget restrictions mean that that it’s more or less impossible to demand that businesses close down. Is enough being done?

MIYASAKA If each and every one of us can be alert, rather than waiting for local bodies to issue alerts, there is no need to panic. The problem is that people forget to be alert and go out carousing in bars. People will not catch the virus if they follow the rules.

INTERVIEWER Does a state of emergency need to be declared?

MIYASAKA No. Declaring a state of emergency does have some value because it forces people to moderate their behavior. However, issuing another state of emergency now would have grave consequences for the economy. Now is not the time to declare an emergency. As long as individuals remain alert, the virus will not spread that easily.

INTERVIEWER The government has chosen the present time to launch its “Go To” travel campaign, although it has excluded Tokyo and its residents from participation. Should we be worried?

MIYASAKA We have known all along that increased movement by the population would result in the virus being passed on again. Increased movement due to the campaign might or might not increase infections, although as long as travelers modify their behavior as required, the virus will not be passed on so easily. There is no need to order businesses or schools to close, with the exception of a few special industries, as long as individuals remain alert.

INTERVIEWER Many more people are working from home now. Is remote working an effective strategy for fighting COVID-19?

MIYASAKA Working from home obviously helps prevent the spread of infection, although just because you take the train to work does not automatically mean you will catch coronavirus. When we speak, a mist of droplets is propagated 2 meters from our mouths, but this volume can be cut by 90 percent by wearing a mask. While the micro droplets that waft out from the sides of our nose and mouth linger in the air for 10 to 15 minutes, they can be dispersed with fans and removed with ventilation. Packed trains are obviously not good, but people don’t need to be overly worried just because their train is a little full. Avoiding rush hour is also an effective strategy. The worst thing is to become so risk-averse that you can’t do anything.

Why Random Testing Won’t Work

INTERVIEWER So a primary cause of the continuation of this epidemic is entertainment districts, and that if countermeasures are taken people can carry on as normal?

MIYASAKA Effectively, yes. By no means do I believe entertainment districts are the only places people are becoming infected, though, as we know the virus has spread to surrounding areas as well. However, as long as we all observe social distancing, wear masks, and take precautions, the virus will not spread any further. Then it just becomes a matter of testing exhaustively in places with a high concentration of cases.

INTERVIEWER I guess we need to increase PCR testing so that we can identify places with high concentrations of the virus.

MIYASAKA Far too few PCR tests are being performed. Capacity needs to be boosted by a factor of ten or twenty. That said, sentinel, or random, testing will not achieve anything. In Tokyo, for instance, Shinjuku, Ikebukuro, and the surrounding areas need to be tested extensively. We need to make much more use of PCR testing to determine routes of transmission. I’m not saying we need to test everyone—rather, that we have to make a concerted effort in areas where it’s warranted. PCR testing is the most important part of that approach.

A PCR test is like a snapshot. You might be negative today, but that’s not to say you won’t be positive tomorrow. Because COVID-19 has a five-day incubation period, a negative PCR test result does not guarantee you are not infected. We need to perform frequent, exhaustive testing of those populations that need to be tested. Many people in Shinjuku started interacting with others again after a negative test result, only to later find that they were positive. It is therefore important to perform testing frequently. It is impossible to test everyone in the population.

As I have been saying all along, rather than relying on PCR testing, we need to make more use of faster, cheaper methods of detecting viral antigens. Tests can be performed on saliva samples, removing the risk of catching the virus at the test facility. While the saliva antigen test is slightly less sensitive than the PCR method, it does have the advantage of being more sensitive to individuals who shed larger amounts of virus. Frequent, repeated viral antigen screening is a much more useful way to prevent the spread of the virus than one-off PCR testing.

The Benefits of Vaccination

INTERVIEWER There is still no vaccine or drug that can fight SARS-CoV-2. Is there a way of boosting our immunity to defend against COVID-19?

MIYASAKA It may be possible for people to eliminate the virus by leveraging their innate immunity. Recent studies show that innate immunity can be trained. We often hear about BCG, a bovine pathogen that also protects humans from tuberculosis. BCG boosts your innate immunity by training it, thereby making your acquired immunity more easily triggered. A look at data from several dozen countries shows a clear trend to lower tuberculosis mortality and morbidity in countries that have embarked on widespread administration of BCG. There are, of course, exceptions. However, the amount of BCG that can be produced for pediatric vaccines is limited, and the vaccine is not produced for adult use.

In Japan, those in their fifties and sixties have gone over 30 years without a vaccination. Conversely, young children are immunized with nearly ten different vaccines, resulting in very low morbidity rates. Children are vaccinated annually, each time stimulating their innate and acquired immunity. This may explain the low incidence of COVID-19 in children and young people. Senior citizens, on the other hand, have not received an immunological challenge since they were last vaccinated decades earlier, and therefore their trained immunity is no longer effective. If senior citizens are happy to endure the inconvenience of being revaccinated against streptococcus pneumonia and influenza, they may receive unexpected benefits.

Differences Between Asia and the West

INTERVIEWER Why are there far fewer infections and deaths in Japan and other parts of Asia than there are in the West?

MIYASAKA There are many factors involved. Genes are part of it, as is the lack of kissing, hugging, and shaking hands in our culture, and the practice of removing one’s shoes indoors. But there’s something else that makes Asians less likely to be infected. BCG is part of the story, but it’s not everything.

One factor is region-specific infections. There are four varieties of nasal cold virus in the common human coronavirus family, which appear in frequent outbreaks in Japanese schools. Around 15 percent of common colds are caused by a common human coronavirus. It is possible that exposure to these viruses for some reason makes you less susceptible to COVID-19. Exposure to region-specific infections boosts your innate immunity, and to an extent stimulates acquired immunity as well. A strain specific to Asia would explain the disparity, although at the moment we don’t know if such a strain exists.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Shinjuku Mayor Yoshizumi Ken’ichi, second from left, patrols host clubs in the city’s Kabukichō entertainment district. © Jiji.)