Growing Global Pressure to Phase Out Coal, but Green Alternatives are Uncertain

Environment Politics Science Technology- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Eye on a Global Shift

The Japanese government has announced its intention to decrease the use of aging coal-fired thermal power plants, which emit large amounts of carbon dioxide, through fiscal 2030. It intends to suspend or discontinue use of around 100 inefficient coal-fired power plants in a policy shift aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The background to this was international diplomacy surrounding decarbonization, with an eye on the US presidential election this November. The European Union and others are beginning to build a new order under the banner of “green energy.” Meanwhile, Japan is coming under increased pressure, and was even accused of being “addicted to coal” by António Guterres, the UN secretary-general. With the possibility that the United States might shift to greener policies, depending upon the result of the November presidential election, a Japanese government official stated that it was important to promote a positive attitude toward decarbonization.

But even the elimination of some coal-fired thermal power plants will not significantly reduce emissions. Also, it is still unclear how Japan will find alternative sources for electric power. With no prospect of restarting nuclear power plants, all eyes will be on Japan’s new administration as it takes the reins, to see if it can advance the use of renewable energy, including off-shore wind and solar power.

Working Group to Address “Fade Out”

On July 3, Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Kajiyama Hiroshi stated that as 2030 approached, the government would ensure the “fade out” of coal-fired thermal power and lead an early exit from the dirty power source. In preparation for this phasing out, the Agency of Natural Resources and Energy established a new working group within the Advisory Committee for Natural Resources and Energy to consider coal-fired thermal power, consisting of a panel of experts under professor Ōyama Tsutomu, Yokohama National University.

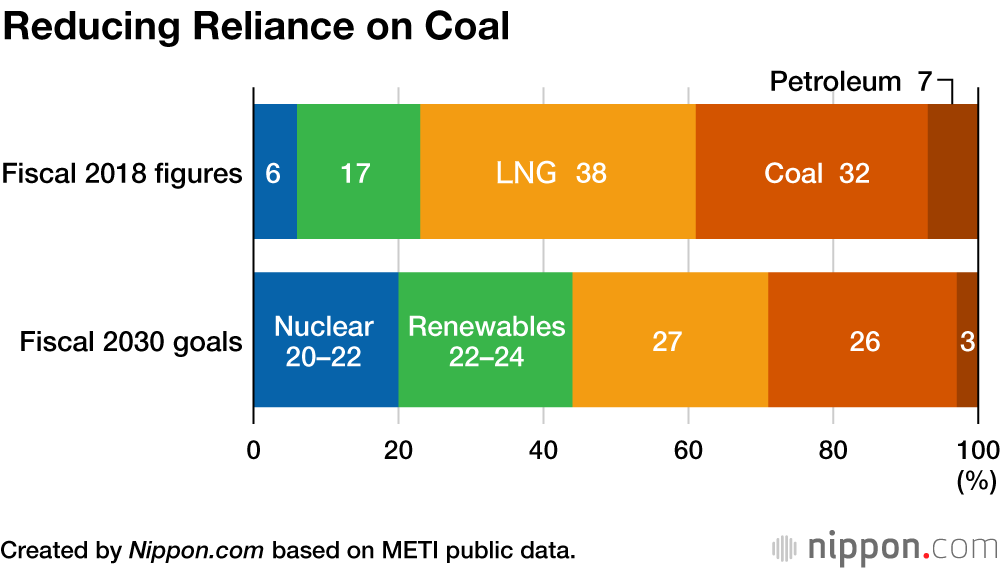

Based on the 2015 Paris Agreement, an international framework to address global warming, Japan has made a public commitment to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 26% from 2013 levels by 2030. To achieve this, the Japanese cabinet approved the nation’s fifth Strategic Energy Plan in July 2018, under which it proposed that coal-fired thermal power would account for just 26% of the total power generated (power supply composition).

But there have been delays in restarting nuclear power plants, which the government positions as an important mainstay power source. Consequently, reliance on coal remains high. The ratio of coal-fired thermal power was 32% of the total in fiscal 2018. Furthermore, Japan has plans to build or replace 17 coal plants nationwide, and the Agency of Natural Resources and Energy concludes that this will raise the country’s reliance on coal to almost 40%.

In order to reduce Japan’s dependence on coal, the working group is deliberating new measures to reduce inefficient coal use. The Agency of Natural Resources and Energy defines this as the older subcritical (Sub-C) pressure and supercritical (SC) pressure technologies. The power generation efficiency of Sub-C is 38% or less, while for SC it is 38%–40%, which is far lower than the latest technologies, which achieve 55%. Sub-C and SC plants account for 114 of the total 150 coal-fired thermal power plants currently operating in Japan, providing 16% of the power supply composition.

In August, the working group began discussions on how their use could be suspended or discontinued.

Concerns of International Isolation

The fade-out policy was also outlined in the fifth Strategic Energy Plan adopted in 2018. But this year, METI and others appear to be approaching it as a matter of greater urgency. Those close to the government note that dramatic changes in international relations concerning green energy have had an impact.

At the end of 2019, the European Commission, which drives EU green policy, announced a radical new plan that adjusted greenhouse gas emission reduction targets from 40% of 2019 levels by 2030 to 50%–55%. In March 2020, the EC unveiled a climate law for reducing net greenhouse gas emissions within the EU to zero by 2050. To help achieve the new target, the panel of experts deliberating the EC’s sustainability financing made a proposal to remove coal-fired thermal power from its investment portfolio in the green sector.

On financial markets, moves spread to restrict investment and lending to carbon-reliant businesses, such as those related to fossil-fuel power generation. Even in Japan, since 2019, three mega financial groups—MUFG, Mizuho, and Sumitomo Mitsui—among others announced that, in principle, they would not finance new coal-fired thermal power projects. But if the EU tightens its rules, investment in coal may be curtailed even further.

As Europe pushes for decarbonization, it is also leading investment in renewable energy, and has expressed its intention to promote technological innovation. The International Monetary Fund leadership, which is well-versed in economic and environmental policies, suggested that taking the initiative in establishing standards and other international guidelines for decarbonization would enable countries to gain an advantage in industrial and economic activities for decades to come. In what might be seen as an attempt to secure a hegemony, even China, one of the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitters, has increased its proportion of electric vehicles and other new-energy cars, and has announced plans to promote technological innovation aimed at cutting emissions. Experts in economic security suggest that China aims to take charge of the global car market through EVs and to create an image of itself as an environmentally considerate country.

Officials from METI and the Ministry of the Environment have expressed concern not only at the EU and China ramping up efforts at forming a new world energy order, but also at the potential for a change in US policy. Since 2017, the United States has given preferential support for the fossil fuel industry, under the leadership of President Donald Trump, who is conspicuously skeptical of climate change. But if former Vice President Joe Biden wins the presidential election this November, there is a high likelihood he will steer the country toward greener policies. Biden has already stated that environmental infrastructure is crucial for the well-being and vitality of the American people and economy, and announced policies for investing $2 trillion in clean energy over four years.

As with the 2016 election, it is too early to predict the election outcome, but those involved in environmental diplomacy are growing increasingly concerned that, should Biden win the election, Japan may find itself isolated as the United States and Europe push policies aimed at decarbonization. In this light, Japan’s “fade out” policy can be seen as preparation for possible radical changes, as international pressure grows, and the US presidential contest looms.

Difficult to End the Coal Addiction

Even with the establishment of a working group to consider phasing out coal, the path for Japan is far from straightforward.

The greatest resistance towards this policy has been expressed by Japan’s iron and steel industry. Of the 114 ineffective coal-fired thermal power plants identified for elimination by the Agency of Natural Resources and Energy, 80 are not operated by power companies, but are run by other companies to provide power to their own facilities. The materials industry is likely to suffer the greatest blow from the changes.

The Japan Iron and Steel Federation told the working group that the industry was taking the initiative in reducing its emissions and promoting energy conservation. Kanda Takaharu, head of the JISF electric power committee, warned that the elimination of in-house power plants would impact the sustainability and global competitiveness of the industry. Makino Hideaki, executive director of the Japan Chemical Industry Association, also expressed concern over the elimination of coal power, stating that it would be necessary to provide additional infrastructure for alternative energy and to guarantee an affordable energy supply.

It is not clear how Japan will secure a stable power supply after the fade out of coal-fired thermal power. For over seven years, the Abe administration continued to focus on nuclear energy and investigated possibilities for restarting nuclear power plants to shore up concerns of an electric power supply shortage from the elimination of coal-fired thermal power. But the cost of the safe restarting of nuclear plants, including terrorism countermeasures, has only expanded. It is also hard to obtain consent from local authorities.

In fiscal 2018, nuclear energy accounted for just 6% of Japan’s power supply composition. It is increasingly evident that it will be extremely hard to achieve the 2030 goal of 20%–22% set in the current Strategic Energy Plan, thereby compensating for the fade out of coal.

In addition, some believe a fade out that only focuses on inefficient coal power will not be enough to erase Japan’s reputation of being addicted to coal. Government officials involved in the formulation of US-related strategy warn that, in the event of a Biden presidency and a shift towards green energy policies, the United States could demand that Japan undertake financial transactions and investment in renewable energy aimed at cutting emissions. In this case, the currently planned elimination of inefficient plants will be insufficient.

Depending upon the international situation following the US presidential election, investment and policy to support expansion of renewable energy may become increasingly important as a bargaining tool in international relations. METI has started to consider more measures supporting renewable energy, with off-shore wind power as a mainstay, in parallel to the fade out of inefficient coal.

All eyes are on the new administration of Suga Yoshihide to see if it can demonstrate concrete plans for making renewable energy the principal power source in its review of the Strategic Energy Plan. It requires acceptance of the reality that Japan has been unable to restart its nuclear reactors. One top manager at a major manufacturer who is also involved in finance believes that it will take political decisions to achieve.

There is no doubt that the current working group deliberations on coal-fired thermal power in Japan, along with the 2020 US presidential election, will have a significant impact on Japan’s future energy policy.

(Originally published in Japanese on September 9, 2020. Banner photo: Jōban Joint Power’s Nakoso Thermal Power Station in Iwaki, Fukushima, partly financed by TEPCO. It employs cutting-edge integrated coal gasification combined cycle technology. © Jiji)