Beyond Abe Diplomacy: Charting a China Policy for a New Era

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

When Prime Minister Abe Shinzō took office in December 2012, relations between Japan and China were icy. Thanks to a combination of factors, including patience and persistence on Japan’s part, they eventually thawed to the point where President Xi Jinping was willing to undertake a state visit to Japan. This is not to say that the bilateral relationship is particularly warm—just that it is no longer cold.

As Abe’s record-breaking tenure draws to a close, let us review and assess his China policy, focusing on critical diplomatic junctures, and consider the challenges facing his successor.

Bottoming Out

As noted above, Japan-China relations were in an abysmal state when Abe took office at the end of 2012, and for the first year, the prime minister seemed content to leave things as they were. Indeed, the relationship plunged to a new low in December 2013, when Abe infuriated the Chinese by visiting Yasukuni Shrine to pay his formal respects to Japan’s war dead.

Shortly thereafter, however, Abe took the first step toward reconciliation. In his January 2014 policy speech to the Diet, he expressed his determination to work for better Japan-China relations, arguing for the resumption of top-level dialogue despite the standoff over territorial issues and calling for a “return to the starting point of a ‘mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests.'”

That year, several Japanese VIPs, including Liberal Democratic Party Vice-President Takamura Masahiko and former Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo, visited China to break the ice. In November 2014, following a series of working-level discussions regarding the Senkaku Islands and other key issues, the two countries announced a four-point agreement to resume dialogue in an effort to build a relationship of mutual trust. Later that month, Abe was able to sit down with Xi Jinping on the sidelines of APEC China 2014. Thus, the patient addresses of the Abe government bore fruit in the first top-level bilateral talks in three years.

The following year saw a flare-up of tensions over China’s historical grievances, but a serious rupture was averted. In September 2016, Abe met with Xi while in China for the Group of 20 summit in Hangzhou. In this way, the two countries were edging toward standard bilateral relations.

On the Road to Normal Relations

During the spring of 2017, the Abe government’s China policy underwent a major course change. Previously, Japan had hesitated to support Xi’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, complaining of a lack of openness and transparency and calling it economically and fiscally unsound. However, in May 2017, LDP Secretary-General Nikai Toshihiro visited Beijing to attend the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, and he took with him a personal letter from Abe to Xi Jinping. Although the content was not made public, it is widely thought to have played up the possibility of Japanese participation in the initiative. In June, at the Nikkei international forum on the Future of Asia, Abe turned the government’s earlier refusal into a conditional yes, saying that Japan could participate providing the conditions of openness, transparency, and economic and fiscal soundness were met. This concession regarding the BRI was another step toward the resumption of reciprocal state visits by the two countries’ top leaders.

In the spring of 2018, China began to take its own steps toward conciliation. On May 4, just before Premier Li Keqiang was scheduled to arrive in Japan for a trilateral summit with the leaders of Japan and South Korea, Xi Jinping conversed with Abe in the first-ever telephone conference between top Chinese and Japanese leaders. This was a clear signal of Xi’s intent to cultivate closer bilateral relations.

Abe’s first state visit to China took place in late October 2018, not long after Vice-President Mike Pence leveled a barrage of criticism against China in his speech at the Hudson Institute. The summit yielded preliminary agreements for cooperation on more than 50 infrastructure projects in third countries—projects that could well be viewed as part of the BRI, even if not explicitly labeled as such. At the time, the agreements seemed to promise a new era in Japan-China economic relations. Thus far, however, practically all the projects have foundered, and the promise remains largely unfulfilled.

When Xi Jinping visited Japan in June 2019 for the G20 Osaka Summit, he agreed to return for a state visit in the spring of 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic has forced an indefinite postponement. Although US-China relations have deteriorated further in the intervening months, Japan and China have managed to maintain the status quo. In anticipation of Xi’s postponed visit, Beijing has managed to quell anti-Japanese vitriol on the historical issue and other hot-button topics. But this cannot last forever.

Japan’s Tightrope Act

Abe’s China policy over the past eight years closely reflects prevailing Japanese attitudes toward China. Although well over 80% of those surveyed in an annual public opinion poll regard China unfavorably, about 70% affirm the importance of Japan-China relations, and the reason most of them give is that China is an important trading partner. Abe’s decision to proceed slowly and cautiously and focus on building economic ties was consistent with public opinion.

What has been missing during the past eight years is a serious and honest discussion of the fundamental changes in the two countries’ relative status and the best way to build a new relationship predicated on those changes. China’s gross domestic product is now three times that of Japan, and the disparity is sure to grow. The regional balance of power is shifting as well. What kind of course should we plot for Japan-China relations given these vastly altered circumstances? Abe has left this fundamental question unanswered.

The Abe government also avoided taking a stand on escalating disagreements between Washington and Beijing. From a security standpoint, Tokyo values its alliance with the United States and is deeply wary of China’s territorial maneuvering. Yet it has indicated a willingness to cooperate with China on the BRI, and it has waffled on the growing calls for decoupling from Chinese industry in the high-tech sector, especially in the area of 5G mobile communications. Tokyo has hesitated to join with the West in condemning China’s human-rights abuses, including the anti-democracy crackdown in Hong Kong, and its position on Taiwan is unclear as well.

Since May 2018, China’s Japan diplomacy has been shaped by Xi Jinping’s goal of improving relations between the two countries. Even so, China has a serious image problem among the Japanese people, and the COVID-19 pandemic has not helped. While Beijing has kept a lid on anti-Japanese discourse in recent months, ongoing incursions around the Senkaku Islands continue to inflame anti-Chinese feeling in Japan.

The truth is that China’s behavior of late—including its aggressive “wolf warrior diplomacy”— has alienated many countries, in the developing world as well as in the West. China’s international prestige has suffered, and this could make it harder for Beijing to strengthen ties with Japan. That said, China has earned some admiration as well, with its “mask diplomacy” and its contributions to global governance. In the years ahead, the United States and China will doubtless continue to jockey for influence.

Toward a Coherent Policy

The basic challenges facing the next administration vis-à-vis Japan-China relations are the very issues left unresolved by the Abe government. In my view, resolving them will require a new assessment of the big picture, with a focus on two fundamental questions.

The first is how we define the Japan-China relationship now and in the years ahead.

Over the past eight years, Japan and China have been engaged in a kind of diplomatic tug of war over the basic structure of their relationship. Between 2008 and 2012, friction over the Senkaku Islands dispute caused bilateral ties to fray. When it came time to repair the damage, Japan sought to turn the clock back to 2008, when the two countries were on friendlier terms. China, however, was determined to redefine the relationship in the light of new realities, including the shifting balance of military power in the East China Sea and China’s vastly superior economic clout. This perception gap made it difficult for Abe and Xi to sit down and engage in a productive discussion about the future of the bilateral relationship.

Given how much the two countries’ relative position has changed, a return to 2008 is clearly impossible. The first task facing the next administration is to develop a coherent and realistic blueprint for a new era in Japan-China relations, with a focus on common interests. This could include drafting the long-delayed “fifth document” setting forth mutually agreed principles on the conduct of Japan-China relations.(*1)

The second question is how to reconcile Japan’s interests with those of the United States and the international community as a whole.

The Abe administration has managed to keep Japan-China relations on a fairly even keel despite the escalation of tensions between Washington and Beijing. But the United States and China are in increasingly sharp conflict on matters ranging from trade and technology to democracy and human rights, and Tokyo is caught right in the middle. Ultimately, Japan will be forced to make a decision on issues like decoupling and the adoption of Chinese 5G technology. It will also come under growing pressure to take a stand on such politically fraught issues as Hong Kong and Taiwan. The Abe policy of strategic ambiguity will gradually become untenable.

At some point, Washington may insist on a coordinated response to the Chinese “threat,” not merely from the other Five Eyes (Australia, Britain, Canada, and New Zealand) but from Japan as well. In the face of hardline American policies, China will doubtless strive to preserve its partnership with Japan. Tokyo will need to enlist the cooperation of other US allies in tempering Washington’s demands if it wants to maintain friendly ties with both countries. But it must also stand firm on the territorial dispute with China. It will be a difficult balancing act.

Of course, many other concrete issues will arise in the coming years. But to grapple with them in an effective and coherent manner, we must first draw up a forward-looking policy framework, building on the “normal” relations restored by the Abe administration. Taking advantage of Xi Jinping’s current Japan-friendly policy, let us initiate a conversation on the shape of the bilateral relationship with Japan’s national interests uppermost in mind.

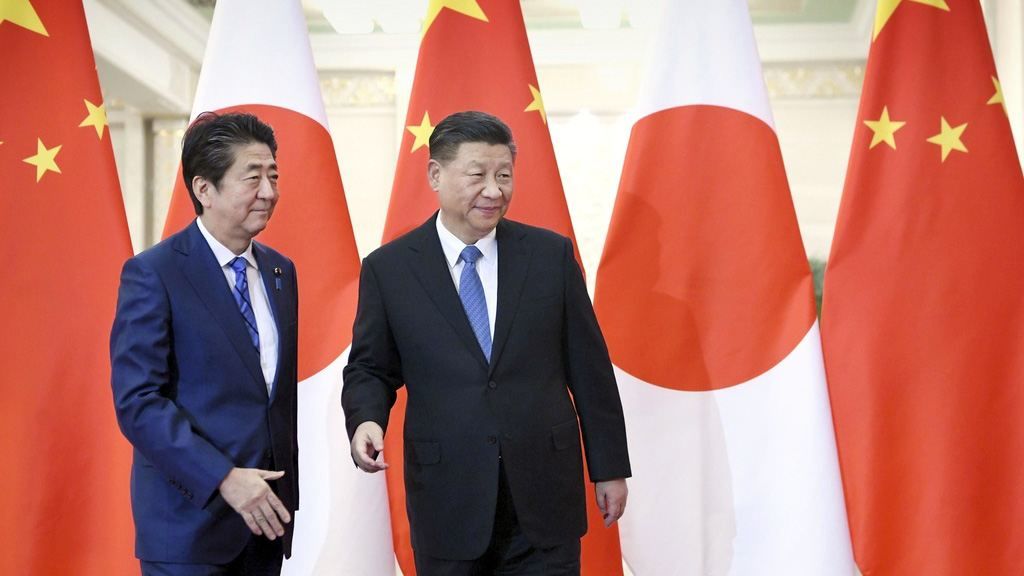

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, left, and Chinese President Xi Jinping meet in Beijing on December 23, 2019, ahead of a Japan-China-ROK conference in Chengdu. © Kyōdō News Images.)

(*1) ^ The first four were the joint communiqué of 1972, the 1978 Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Japan and the People’s Republic of China, the joint declaration of 1998, and the joint statement of 2008.