Forging a New Anglo-Japanese Partnership

Japan and “Global Britain”: Toward a New Anglo-Japanese Alliance?

Politics World- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The British Carrier Strike Group 21 is en route to Japan and surrounding waters, where it will conduct joint drills with Japanese and American naval forces. This historic deployment heralds the return of British naval power to the region “east of Suez” after a half-century hiatus. It also speaks to the rise of a new bilateral security relationship that has been compared to the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of the early twentieth century. It is not an entirely fanciful comparison.

Recalling Tōgō and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance

On December 14, 2017, Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs Kōno Tarō and Minister of Defense Onodera Itsunori gathered with their British counterparts, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson and Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson, for the third Japan-UK “two plus two” ministerial meeting in Greenwich—home of the Royal Naval Observatory, the Prime Meridian, and Greenwich Mean Time. In a December 15 piece in the Daily Telegraph, John Hemmings, then director of the Asia Studies Centre at the London-based Henry Jackson Society, wrote that the setting, rich in symbolism, “pointed not only to the two countries’ shared naval history, but to a common naval future.”

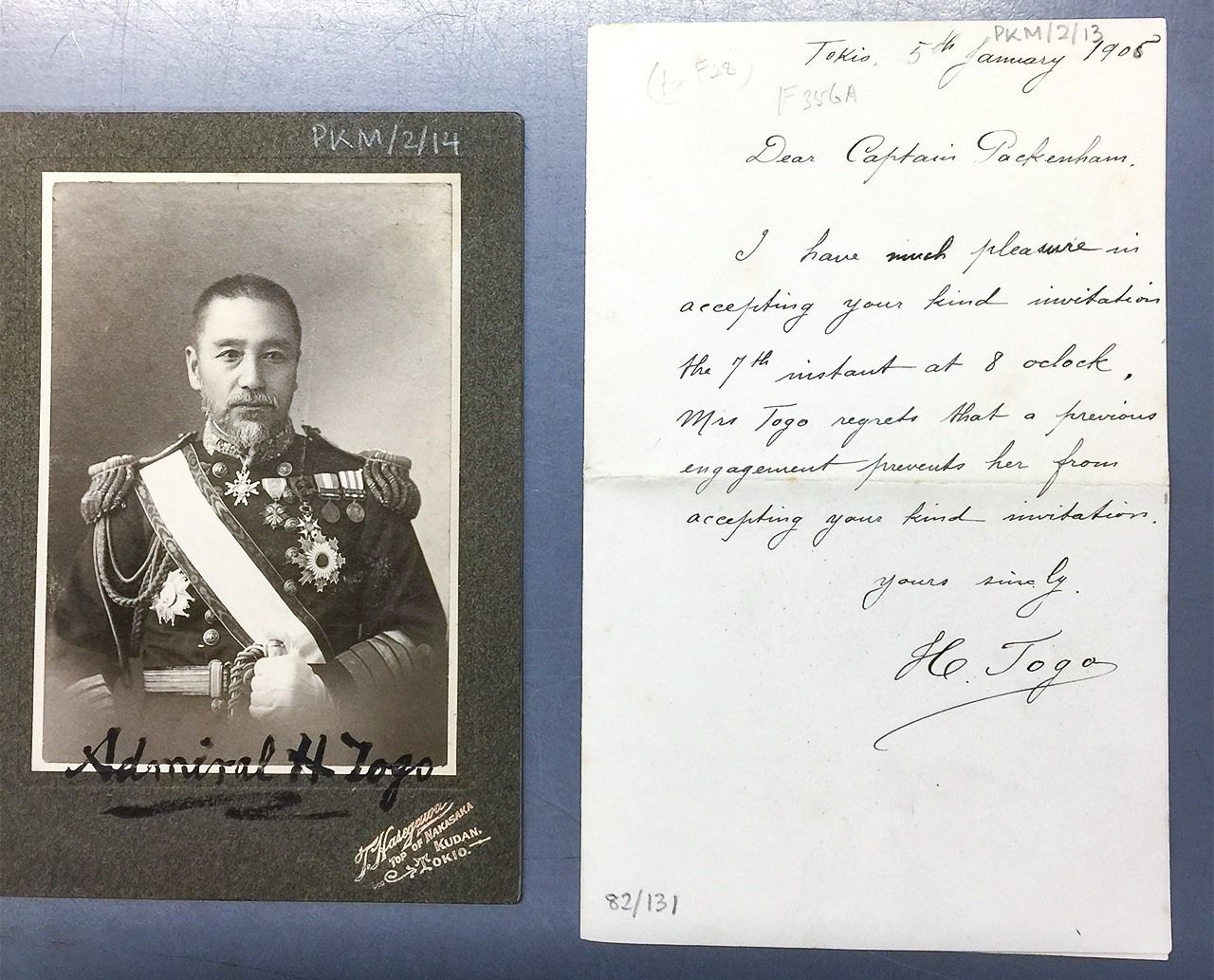

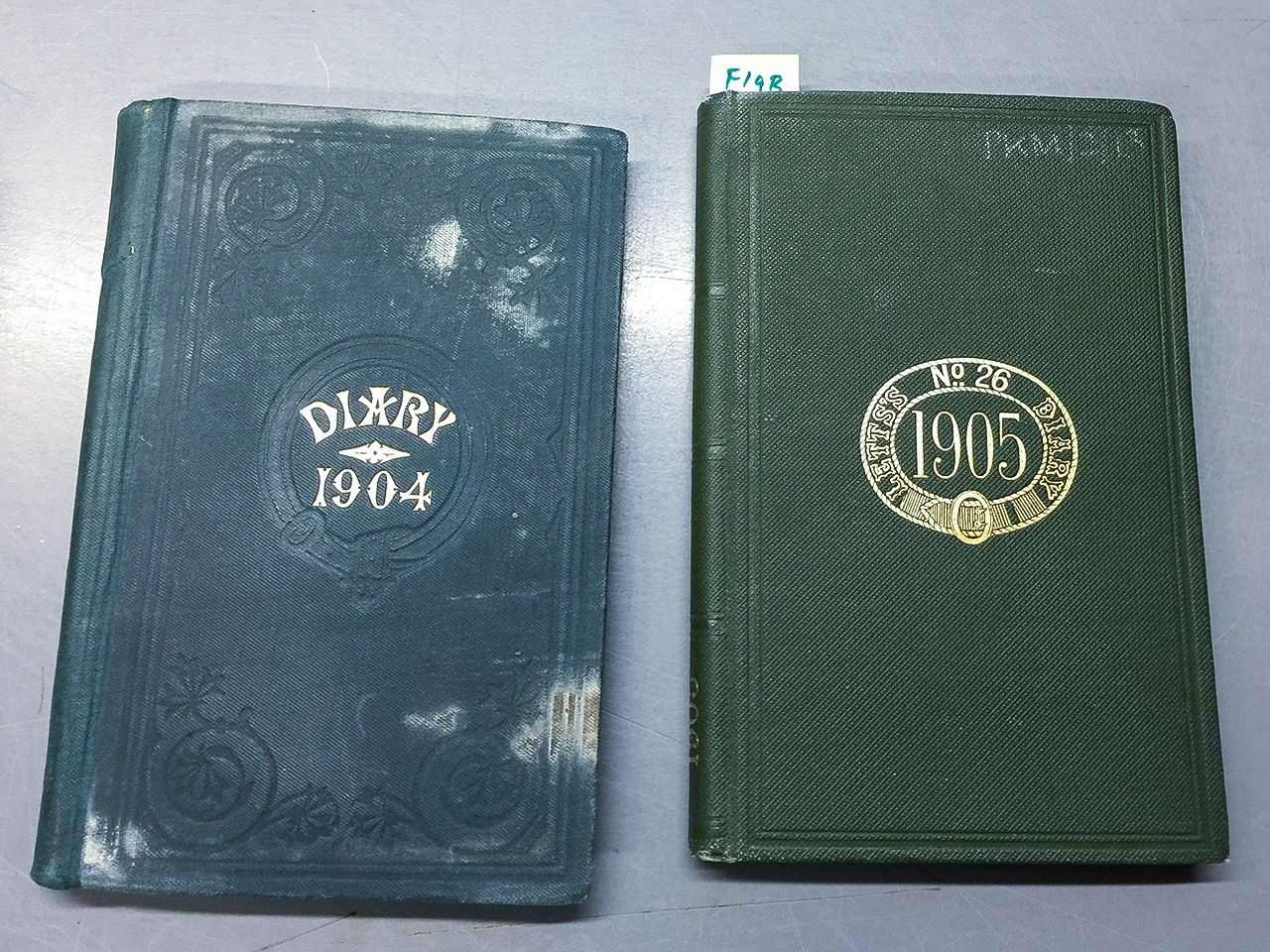

As if to drive the point home, the British side arranged for a special airing of naval artifacts testifying to that shared history. The items were originally in the possession of Admiral William Pakenham (1861–1933), a British naval officer who served as an attaché in Tokyo and a military observer during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5). They consisted of Pakenham’s diaries for 1904 and 1905 and two tokens of his friendship with the Japanese naval hero Marshal-Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō (1848–1934): a hand-written note by Tōgō and a photographic portrait.

Photo portrait of Tōgō Heihachirō and Tōgō's handwritten note to William Pakenham. (Courtesy National Maritime Museum, Greenwich)

Diaries of William Pakenham. (Courtesy National Maritime Museum, Greenwich)

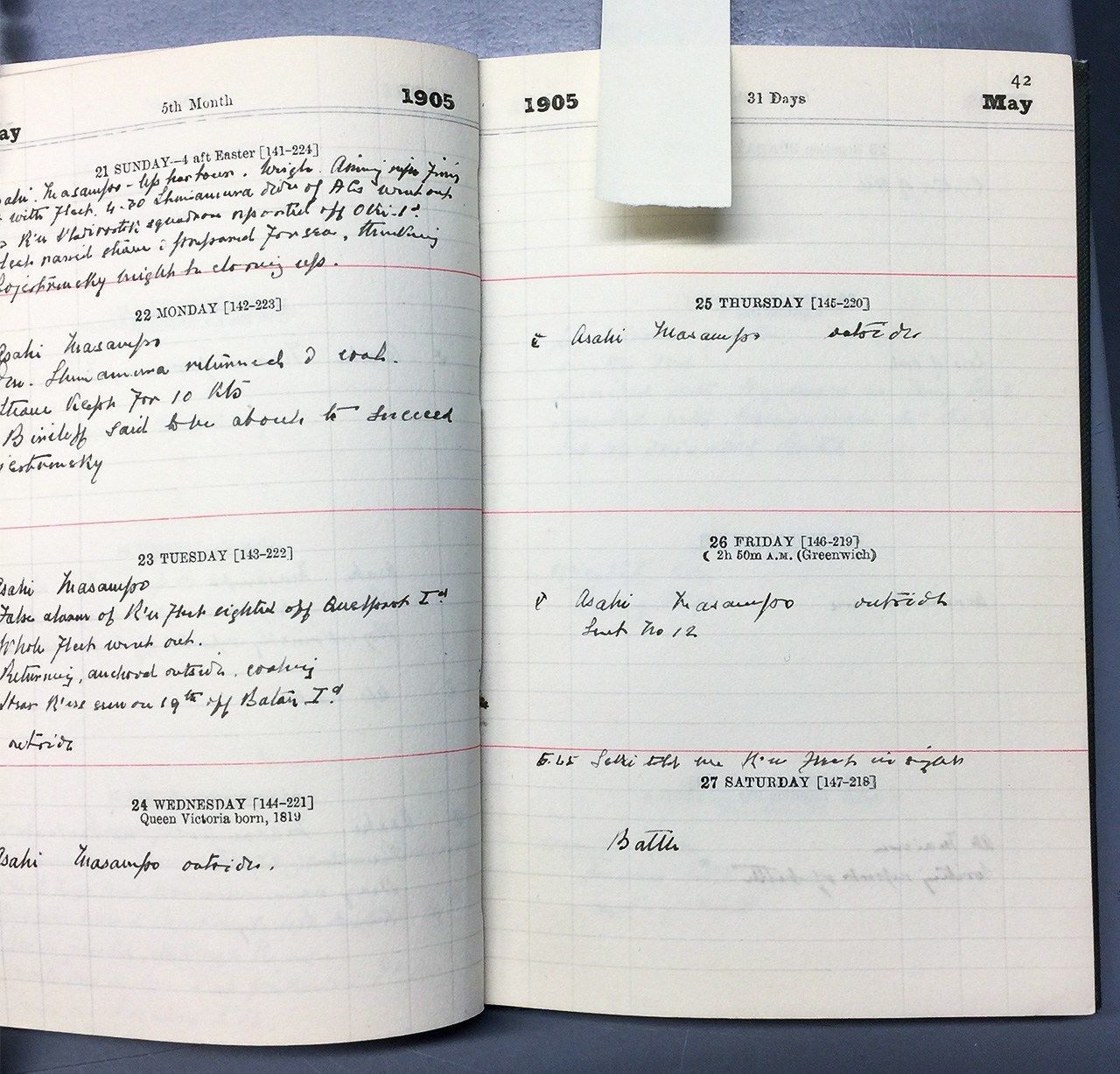

Page from William Pakenham’s diary, including the entry for the Battle of Tsushima, May 27, 1905. (Courtesy National Maritime Museum, Greenwich)

In early January 1905, Captain Pakenham had invited Admiral Tōgō, commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, to a reception and banquet at Pakenham’s home in Tokyo to celebrate the Russians’ surrender of Port Arthur on January 2 that year, after a 150-day siege. In a note dated January 5, 1905, Tōgō cordially accepts Pakenham’s invitation and conveys Mrs. Tōgō's regrets, signing the note “H. Tōgō.” He is thought to have enclosed the photo (later inscribed by Pakenham “Admiral H. Tōgō”) along with his RSVP. Pakenham inserted both documents in his diary, and the group is now housed in the National Maritime Museum.

As museum curator Andrew Choong Han Lin explained to the four ministers gathered at Queen’s House in December 2017, the destruction of Russia’s Far East Fleet and the fall of Port Arthur marked a turning point in the Russo-Japanese War. Still ahead, however, was the decisive battle with Russia’s Baltic Fleet, which had set sail for the Far East two months earlier. Choong believes that Tōgō sent Pakenham the photo of himself in full naval uniform as an expression of his determination to meet the coming challenge and put an end to Russia’s expansionist ambitions in the Far East.

On May 27 that year, Tōgō led the Combined Fleet to a crushing victory over the Baltic Fleet in the Battle of Tsushima, effectively ending the war and earning himself the sobriquet Nelson of the East. Pakenham witnessed this naval “battle of the century” at close range, risking life and limb aboard the Japanese battleship Asahi.

Quite a few military attachés and observers took part in the Russo-Japanese War, but the largest number—33—came from Britain, which had concluded a historic alliance with Japan in 1902. Pakenham, attached to Japan’s First Fleet, spent much of the war aboard the battleship Asahi, which had been built in a British shipyard in Scotland. In the Battle of Tsushima, the Asahi, with Pakenham on board, was in the thick of the action as one of four battleships in the First Division. Pakenham made note of the event in his diary with a single word: “Battle.”

At the Greenwich two-plus-two meeting 112 years later, British officials made a point of sharing these rare documents as a reminder of this special historical relationship. The meeting yielded a three-year defense cooperation plan and a joint statement in which the two governments “expressed their commitment to elevating their global security partnership to the next level” and agreed to cooperate closely to maintain a “free and open Indo-Pacific” (a Japanese initiative). Foreign Minister Kōno welcomed Britain back to “east of Suez” after a half-century absence, and Defense Secretary Williamson called Japan “one of our closest partners in the Asia Pacific region.” Following the meeting, Onodera visited Portsmouth Naval Base, where he became the first foreign minister of state to board the world-class aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, which had been formally just commissioned the previous week. The idea of a joint drill with the aircraft carrier JS Izumo was floated at that time.

As Professor Ian Neary of the University of Oxford commented in an interview with Xinhua, “Britain and Japan are seeing themselves as allies, or semi-allies.”

Military cooperation progressed rapidly in the wake of the 2017 agreement. During 2018 and 2019, the Royal Navy frigates HMS Sutherland, HMS Argyll, and HMS Montrose—deployed to the region to monitor for illegal trading activity with North Korean vessels—conducted exercises with Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force in the waters off southern Honshū. They were the first joint naval maneuvers between Japan and Britain since the termination of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance following World War I. In October 2018, British Army troops were deployed to Japan, where they engaged in training with Japanese Ground Self-Defense Forces. It was the first time any British troops (or any foreign troops other than Americans) had conducted military exercises on Japanese soil. Trilateral naval exercises involving US Navy P-8A maritime patrol aircraft have also been held.

Japan and Britain are stepping up collaboration on military technology as well. They have teamed up for the development of an air-to-air missile that will incorporate a radar system developed by Mitsubishi Electric in a British-made Meteor missile, with a prototype to be completed sometime in 2022. The missile, which would be mounted on Japan’s F-35 stealth fighters, would be the most advanced weapon of its type.

A Natural Partnership

A number of factors have converged to fuel the recent upsurge in Japan-UK security cooperation. Foremost among these are the growing regional security threats from North Korea and from China, which now surpasses the United States in the size of its navy (according to a September 2020 report from the US Department of Defense). From Tokyo’s standpoint, security cooperation with Britain is a way to bolster deterrence while reducing Japan’s heavy dependence on the United States, its only formal ally.

Prior to the 2017 agreement, then Prime Minister Abe Shinzō had succeeded in loosening constitutional constraints on Japanese military cooperation, including arms exports and imports and participation in collective self-defense. “In the context of collective defense,” noted Neary, “Japan may now come to the assistance of its ally, which is something that previously would not have been permitted.”

For Britain, which has worked hard to strengthen economic ties with the Indo-Pacific since voting to leave the European Union in 2016, defense of the region’s sea lanes has become an urgent priority. Of course, the EU also has an economic interest in keeping those lanes open, and Hemmings suggests that a sound post-Brexit strategy might be for Britain to concentrate its naval power on the defense of European trade routes from Suez to Singapore, while Germany accepts a greater share of the responsibility for Eastern Europe.

More generally, Hemmings quotes Simon Chelton, a former British defense attaché in Tokyo, as observing that “Britain and Japan have similar core defense needs, as island nations with close defense ties with the United States, with broadly equal defense budgets and very similar requirements for maritime and air equipment in particular.”

Historic Deployment of Britain’s Carrier Strike Group

This brings us up to May 22, 2021, when the HMS Queen Elizabeth (the same carrier that Defence Minister Onodera toured in December 2017) set out from Portsmouth on its maiden voyage as flagship of Britain’s Carrier Strike Group. During its 28-week deployment, the group will sail through the Suez Canal and visit some 40 countries on its way to the South China Sea and the waters around Japan, including the Senkaku Islands. Boris Johnson termed it “the UK’s most ambitious deployment in two decades.”

On January 19, 2021, the US Defense Department announced that the Navy and Marine Corps would participate in the task force anchored by the HMS Queen Elizabeth. Marine Corps F-35B stealth fighters have joined the Queen Elizabeth for the group’s Western Pacific deployment. USS The Sullivans, a Navy Aegis guided missile destroyer, will be taking part as well. The aim is to showcase close regional cooperation between the United States and Britain in the face of China’s rapid military expansion.

The long-term deployment of Britain’s Carrier Strike Group to the Western Pacific will kill several birds with one stone. While strengthening defense cooperation between Britain and its partners in Asia, particularly Japan, it will also lighten the burden on the United States, with which Britain enjoys a “special relationship”—a favor that Washington is likely to remember. More than anything, however, joint drills and maneuvers including Japanese, American, and British forces will substantially boost deterrence and enhance Japan’s national security.

In 1971, a half century ago, Britain withdrew from its military bases in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. Two years later, in 1973, it joined the European Community, the predecessor to the EU, and began building a foreign policy predicated on membership in the EU and strong relations with the United States. When the British people voted to throw off the European yoke in the 2016 Brexit referendum, Britain began pivoting back to Asia as a matter of urgency. As Britain stages its return to “east of Suez,” Japan has welcomed it enthusiastically and emerged as a key partner in the region. If Britain succeeds in redefining itself as a major naval power in the Indo-Pacific and a de facto ally of Japan, the spirit of Tōgō Heihachirō will surely rejoice.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: (From left) British Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson, Japanese Defense Minister Onodera Itsunori, Japanese Foreign Minister Kōno Tarō. and British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson examine historical materials pertaining to the Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Russo-Japanese War during the third Japan-UK Foreign and Defense Ministers’ Meeting in Greenwich, London, on December 14, 2017. © AFP/Jiji. Photos within the article taken by Okabe Noboru; courtesy National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.)