The Birth of the Chinese Communist Party and Other Mysteries

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Communist Party of China will observe its 100th anniversary in July 2021. The government plans to celebrate the occasion with a series of programs and events, including symposiums, performances, and awards ceremonies—with considerable emphasis, one supposes, on the nation’s recent triumph over the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis. The climax, no doubt, will take place on July 1, traditionally observed as the anniversary of the party’s founding. I say “traditionally,” because nothing of particular significance actually happened on July 1, 1921. In fact, my research strongly supports the notion that the party’s founding occurred the previous year.

Nonsignificance of July 1

In 1938, the CPC’s leadership decided to hold an event commemorating the party’s founding, and they elected to equate the birth of the party with the convening of the First National Congress in 1921. Most of the participants were fairly certain that the meeting had taken place in the month of July, but no one in the party had preserved a written record of it, and neither Mao Zedong nor anyone else could remember with certainty the date on which it had been held. For convenience, they decided to designate July 1 the opening date of the First National Congress and hence of the party’s founding.

It was not until the late 1950s, about a decade after the Communists took control of China, that a Russian-language report on the event surfaced. That report indicated that the conference had opened on July 23, 1921, in the home of a party member living in the Shanghai French Concession. By then, the CPC had been celebrating July 1 for two decades, and it was thought best not to alter the party’s official anniversary at that point. In the official accounts, therefore, July 23 is now identified as the day on which the First National Congress was held, though its foundation day is still observed on July 1.

There is one other record connected with the First National Congress that bears mentioning. The Japanese novelist Akutagawa Ryūnosuke (1892–1927), who spent about four months in China as a reporter during 1921, visited the home of a young Shanghai intellectual by the name of Li Hanjun (1890–1927) about three months before the First National Congress. Li was a core figure in the nascent Communist Party, and it was at his house in the French Concession that the First National Congress was held. In his travel journal (Shanghai yūki), the novelist describes the visit and the home’s interior. The historic building has been restored and turned into a museum, including a meticulous recreation of the room where the meeting was held. It is very much as Akutagawa described it.

A recreation of the room in Shanghai where the First CPC National Congress was held on July 23, 1921.

We have a clear picture, therefore, of when and where the First National Congress was held. But while the CPC has traditionally equated that event with the party’s founding, logic suggests that the organization must already have existed before it could hold a national convention attended by delegates from various regions. So, when and where did the Communist Party of China come into existence as an organization?

The Comintern Connection

The founding of the CPC can be attributed to the educator and reformer Chen Duxiu (1879–1942). Chen was the publisher of a journal called Xin Qingnian (La Jeunesse, or New Youth), which championed progressive Western-influenced thought while criticizing traditional Chinese society and culture. In 1919, when he was serving as dean of Peking University, Chen began using the pages of his journal to introduce readers to socialist thought and the labor movement. Later in the same year, he resigned from the university, and in February 1920, he moved to Shanghai, taking his magazine with him.

About two months later, a Russian Communist Party official by the name of Grigori Voitinsky arrived in Beijing from Vladivostok to explore the possibility of propagating communism in the Far East. After making contact with Li Dazhao (1889–1927)—Chen’s former associate at Peking University and another seminal figure in the founding of the CPC—Voitinsky proceeded to Shanghai, where he met with Chen. That was when Chen set about organizing a group of young Shanghai intellectuals sympathetic to socialism and, with guidance from the Comintern (Communist International), taking steps to establish a communist party in China. At Chen’s urging, fellow activists in other key cities began organizing as well. In the north, Li Dazhao introduced Beijing’s reformist intelligentsia to socialist theory, while in the south, Tan Pingshan and his entourage performed the same role in Guangzhou.

In this way, Chen’s efforts to establish a Chinese communist party quickly gained traction, and by the fall of 1920, an organization had more or less taken shape. The campaign appears to have climaxed in November, with the publication of the first issue of Gongchandang, or The Communist (literally, The Communist Party) and the drafting of the first Manifesto of the Chinese Communist Party (Zhongguo Gongchandang xuanyan).

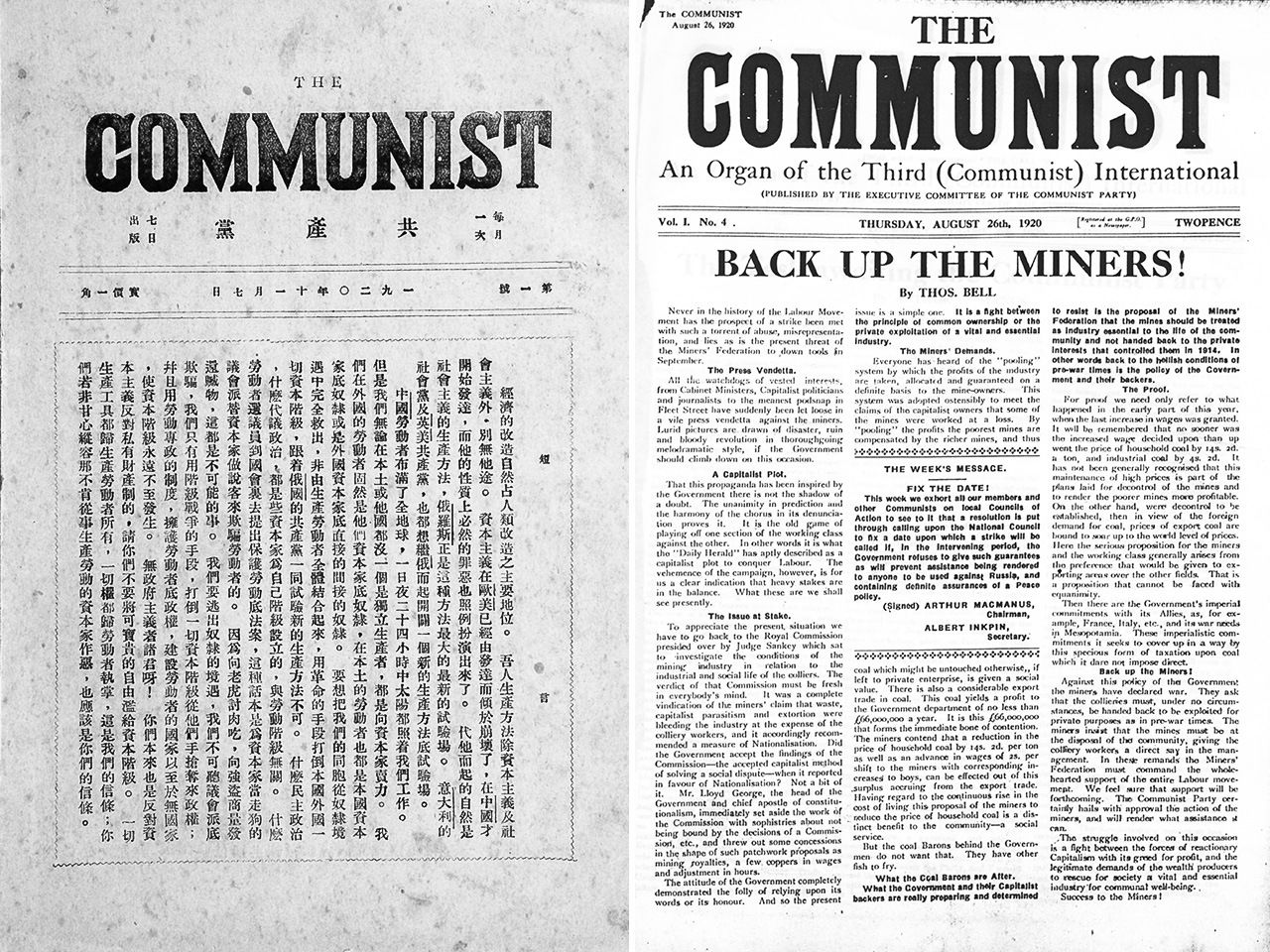

Gongchandang was an internal monthly bulletin published by Chen Duxiu’s Shanghai group. In its inaugural issue, an item titled “Shijie xiaoxi” (World News) features the phrase “our Chinese Communist Party,” marking the first time the group referred to itself in those terms in a printed publication. It can hardly be accidental that the inaugural issue of Gongchandang is dated November 7, the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Moreover, the magazine’s distinctly un-Chinese cover design—with its English title The Communist emblazoned in large letters over the first page of text—owes an obvious debt to the official organ of the newly established British Communist Party (British Section of the Third International), published earlier the same year.

The bulletin Gongchandang (left), published in November 1920 by Chen Duxiu’s Shanghai group, and its British counterpart, The Communist, dated August the same year. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Further proof of the Shanghai group’s intent to launch a communist party in November 1920, to coincide with the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, is the group’s completion that month of a Manifesto of the Chinese Communist Party, setting forth the aims of the communist movement in China. It is worth noting that this declaration, just 2,000 characters in length, closely matches the editorial mission statement printed in the first issue of Gongchandang.

It seems clear from the available evidence, in short, that an organization calling itself the Communist Party of China—complete with an official bulletin and a manifesto—was born at the home of Chen Duxiu in Shanghai in November 1920, a full eight months before the First National Congress. My own conclusion, accordingly, is that the real centennial of the CPC’s founding has already passed. Of course, the party is free to date its own establishment using whatever criterion it chooses (including the opening of the First National Congress), and it is also free to commemorate the event on a different day entirely. This is simply one of several murky areas on which I have sought to shed light through scholarly research.

Unsolved Riddles

A number of riddles also surround the First National Congress. For example, without naming names, the aforementioned Russian report states that there were 12 Chinese party members in attendance, in addition to two representatives of the Comintern. However, based on subsequent recollections of Chinese participants, the party histories all list 13 CPC delegates. The official explanation for the discrepancy is that the Russian report omitted Bao Huiseng, who was not a full-fledged delegate but merely attending in place of Chen Duxiu. However, there is no evidence to support this theory, nor does it seem likely that such a fine distinction would be made at this early stage in the party’s history. It is a point on which scholars disagree.

This brings us to the question of why neither the party’s de facto founder, Chen Duxiu, nor his close associates Li Dazhao and Tan Pingshan made it to this presumably historic meeting. There is no indication of a falling out that would account for their absence. Perhaps the simplest explanation is that the event’s historic nature was not apparent to the participants at the time.

The National Congress of the CPC has become a weighty occasion full of pomp and circumstance, but attitudes appear to have been different back in those early days. In his interviews with Edgar Snow, Mao Zedong, who was among those present at the first congress, recalled missing the second, also held in Shanghai, even though he had already traveled to Shanghai from Hunan. “I forgot the name of the place where it was to be held, could not find any comrades, and missed it,” he confessed (Red Star over China, 1937). Such carelessness may strike one as odd, but I would submit that it reflects the mindset of Mao and other Communist leaders in those early days. Perhaps by focusing like a laser on such details as the number of delegates present, later historians are missing the forest for the trees.

The Closing of the Chinese Mind

As a scholar specializing in the history of the CPC, I have delved deeply into these and other circumstances surrounding the party’s establishment. Some years back, I published my findings and speculations in a book, Chūgoku Kyōsantō seiritsu shi (History of the Formation of the Communist Party of China). The book was translated into Chinese and published in Beijing in 2006 without revisions or omissions, even though it differed with the official party account on a number of points. Its appearance attracted considerable notice in China, and the first run sold out quickly. The publisher contacted me about a second printing, and I readily gave my assent.

The Chinese edition of Ishikawa’s 2001 book on the birth of the Chinese Communist Party, published in Beijing in 2006.

A while later, I was informed that the book was undergoing a second screening, and that was the last I ever heard from the publisher. More than a decade went by. With the government tightening its grip on publishing, I gave up hope of another printing in mainland China and arranged instead to have a revised edition published in Hong Kong. The new Chinese edition is scheduled to come out in June this year. Bringing it to the mainland will be difficult, I am told.

No doubt a flood of new works on the illustrious history of the Chinese Communist Party will appear during the course of this centenary year. It remains to be seen how many of them will stand up to scholarly scrutiny.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Site of the First National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, Shanghai. Photo courtesy of the author.)