How the War with Japan Saved the Chinese Communist Party

History Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) was a devastating ordeal for China, but it was also, paradoxically, the salvation of the Communist Party of China. On the eve of the July 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident, the badly depleted CPC was confined to a rural enclave in Northwest China, its very survival in doubt. In the following, I explain how a combination of luck and shrewd calculation paved the way for the party’s astonishing comeback.

The Long March

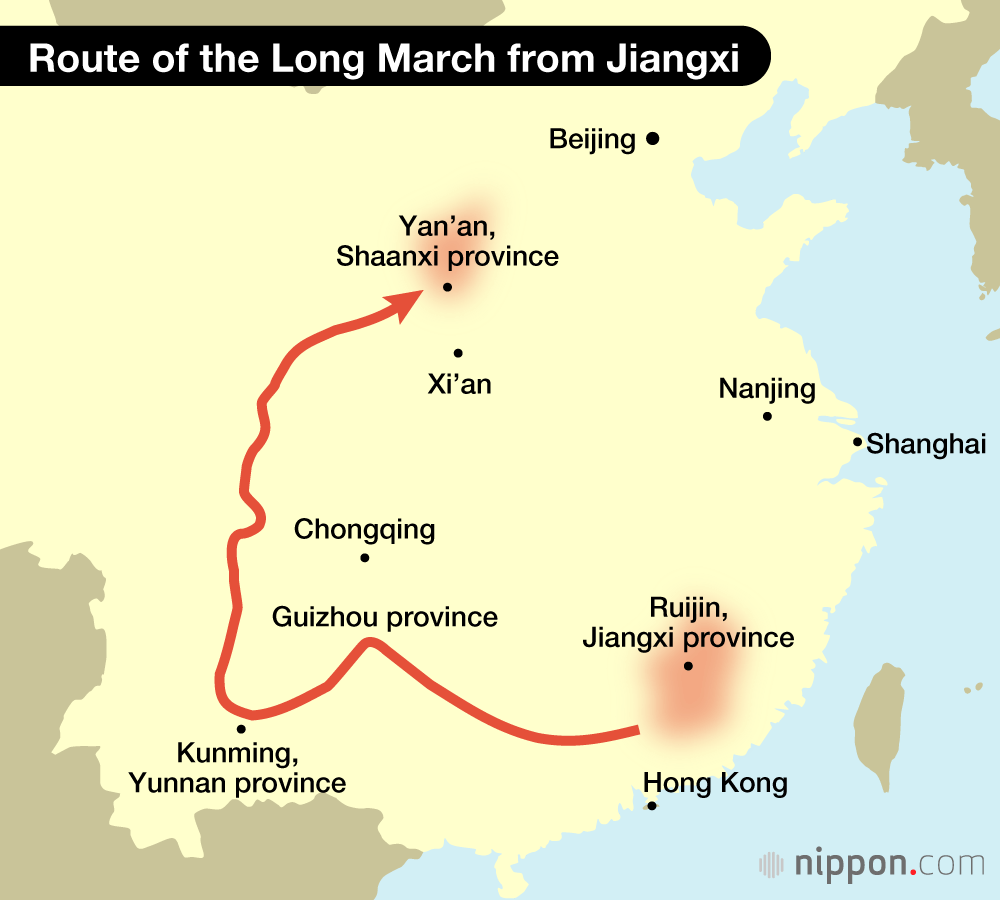

During the first half of the 1930s, the Nationalist Chinese government in Nanjing, led by Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang (KMT), launched a series of encirclement campaigns targeting Communist strongholds around the country. By the fall of 1934, the KMT’s National Revolutionary Army had encircled the CPC’s central base area in Jiangxi province. In a desperate bid to avoid annihilation, the Communist forces, which had numbered some 300,000 at their peak, slipped through the enemy lines and escape the siege. Thus began the circuitous Long March, which took the Communists ever farther inland. By the time the Red Army seized Zunyi in Guizhou province in January 1935, its numbers had been reduced to about 10,000.

The army from Jiangxi eventually met up with another force under the command of Zhang Guotao, which had been driven from its base in northern Sichuan. However, the party leadership was divided on the march’s ultimate destination. Zhang insisted on proceeding south, over the objections of Mao Zedong, and his rebellion threatened to split the party in two. In the end, Mao and Zhou Enlai led the bulk of the army north, across the Daxue Mountains and into Shaanxi. The Long March finally came to an end in late 1935, when they joined up with local forces in northern Shaanxi province.

Two Lifelines

In Yan’an, Shaanxi province, the CPC was finally able to regroup and establish a new permanent base. But it was an inhospitable region, ill-suited to supporting an army. As straggling and scattered units continued to make their way north, the CPC was facing the nearly impossible challenge of feeding its army and others converging on the area. It was the Communist International, controlled by Moscow, that saved the party from that looming crisis.

The CPC itself had started out as a local chapter of the Comintern. For the first decade after the party’s establishment, the Comintern had essentially funded the organization with monthly stipends. Thereafter, it had shifted to infusions on an as-needed basis, but that assistance remained substantial. However, the CPC had lost radio contact with the Comintern after abandoning its central base area in Jiangxi. In June 1936, it was finally able to restore the radio link from its new base in Yan’an. The roughly $2 million in aid that the CPC subsequently received from the Comintern allowed the party to feed its troops and avert disaster.

Another lifeline was the cooperation of strongman Zhang Xueliang, who had pledged his allegiance to the Nationalist government after his father, a Manchurian warlord, had died in 1928. As commander of the Northeastern Army, Zhang Xueliang had taken the fall when the Japanese—encountering little resistance from Nationalist forces—had invaded Manchuria in 1931. After a brief exile in Europe, Zhang had returned to China and the service of Chiang Kai-shek, who ordered him to lead his army against Communist forces in the Northwest. In October 1935, at Chiang’s orders, Zhang stationed his army in Xi’an, south of Yan’an.

But Zhang rapidly lost patience with Chiang’s policy of “internal pacification before external resistance,” which targeted the Communists while tolerating the Japanese, even as the situation in North China grew ever more perilous. After losing three divisions fighting the Communists, Zhang sent out feelers in hopes of establishing a dialogue with the CPC. The aim was not just to stop the civil war but also—and perhaps more importantly—to secure the support of the Soviet Union in the war against Japan.

The CPC, for its part, had been under pressure from the Comintern to form a broader anti-Japanese national front. In late 1935, having adopted a resolution to that effect, the party leadership had begun actively exploring avenues for cooperation with Zhang Xueliang.

In April 1936, Zhou Enlai and Zhang Xueliang met in Yan’an and agreed to mutual non-aggression with the goal of a united front against the Japanese, while Zhang secured a promise of support from the Comintern. The CPC forged a similar alliance with Yang Hucheng and his Northwestern Army, thus vastly improving the security environment of the party’s new base.

Back in Nanjing, however, Chiang Kai-shek remained intent on wiping out the Communists in their remaining stronghold. Frustrated by the lack of progress on that front, he flew to Xi’an in December 1936 to oversee the military campaign himself. This set the stage for the famous Xi’an Incident.

The Xi’an Incident and Its Aftermath

On December 12, 1936, bodyguards of Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng stormed Chiang Kai-shek’s quarters and detained the Nationalist leader. This quasi coup placed the CPC in a delicate situation. The Soviet government, under Joseph Stalin, had decided that the best strategy for countering fascism and Japanese expansion was a united KMT-CPC front led by Chiang Kai-shek. Accordingly, the Comintern instructed the CPC to negotiate a peaceful resolution to the Xi’an Incident.

Had Chiang refused to negotiate, the Nationalist army would doubtless have moved quickly to encircle both the CPC and the Northeastern Army. Ultimately, Chiang did negotiate, however, and the two sides settled the standoff by means of a verbal agreement: The KMT would halt its military campaign against the Communists on the condition that the CPC place its forces under the Nationalist government’s command. Chiang was released on December 25 and returned to Nanjing.

This was not a formal written agreement, and its terms suited neither side. The Nationalist government never did provide the level of financial support it promised to the Communists, and the Communists never considered actually handing over command of their army to the KMT. Right up until the eruption of all-out war with Japan, the future of the united front—and of the Communist Party of China—was in serious doubt .

What altered this dynamic and ultimately restored the CPC’s fortunes was the outbreak of full-scale war, precipitated by the Marco Polo Bridge Incident on July 7, 1937. In a telegram dated July 8 (though actually sent out two days later), the CPC’s leadership issued a call for national unity against the Japanese and urged cooperation between the KMT and the CPC. On July 15 it drafted a manifesto for the creation of a Nationalist-Communist united front, the dissolution of the Chinese Soviet Republic, and the reorganization of the Communist forces into divisions (nominally) under the National Revolutionary Army.

At first, Chiang Kai-shek dismissed the seriousness of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident and was unwilling to allow Communist troops to operate under independent command. However, at the end of July, with the situation growing dire, he yielded and agreed to the proposed reorganization of the Communist forces (as a legitimate army) under independent command in exchange for their rapid deployment against Japanese forces in the North.

In September, in a bid to further speed deployment of the Communist forces against the Japanese, Chiang went further and agreed to announce the formation of a united front in a statement following the CPC’s own wording, effectively recognizing the legality of the Communist Party and its legitimate control over certain regions. This greatly facilitated the CPC’s subsequent expansion.

The crucial questions of what regions would be under Communist control and what kind of support the central government would provide were left unresolved, with the understanding that they would be settled by a joint committee of the two parties at the end of the year. However, when it became apparent that no degree of compromise with the CPC was likely to draw the Soviet Union into the struggle against Japan, the KMT adopted delaying tactics. The Communists were thus obliged to fend for themselves and turned again to the Comintern for financial support.

![Receipt for payment of $300,000 from the Communist International, dated April 28, 1938. The document bears the signature and seal of Mao Zedong. (Reprinted from Victor Nikolaevich Usov, Sovetskaya razvedka v Kitae: 30-e gody XX veka [Soviet Intelligence in China: The 1930s]. Moscow: Tovarishchestvo Nauchnykh Izdanii KMK, 2007.)](/en/ncommon/contents/in-depth/894020/894020.jpg)

Receipt for payment of $300,000 from the Communist International, dated April 28, 1938. The document bears the signature and seal of Mao Zedong. (Reprinted from Victor Nikolaevich Usov, Sovetskaya razvedka v Kitae: 30-e gody XX veka [Soviet Intelligence in China: The 1930s]. Moscow: Tovarishchestvo Nauchnykh Izdanii KMK, 2007.)

In the early stages of the war, the Communists actively engaged the Japanese in open combat as part of the party’s strategy to secure legal status. These early operations dealt a significant blow to the Japanese in Shanxi and other parts of the North. But Mao Zedong was extremely distrustful of Chiang Kai-shek’s intentions vis-à-vis the CPC. Once the Communists had secured key concessions, including the promise of legalization, the military strategy shifted to guerrilla operations in the mountains in an effort to preserve and boost the party’s military strength vis-à-vis the KMT. This strategy was coupled with a massive effort to recruit new members. As a result, the CPC was able to boost its membership from about 30,000 at the outset of the war to some 800,000 by 1940, while raising an army of about 500,000.

Crisis and Reform

Early in 1940, the Japanese army, seeing that the Communists’ ranks were swelling, began conducting military sweeps of the countryside, particularly in the North, in an effort to root out the Red Army and its supporters. In response, the Communists, who had acquired a measure of confidence after three years of war, decided it was time to shift to a more aggressive strategy. Thus was born the Hundred Regiments Offensive, a large-scale, coordinated campaign against Japanese-held cities and railway lines. While the offensive succeeded in damaging some Japanese infrastructure and bases, the destruction wrought by the Japanese in retaliation was far greater. Moreover, the all-out campaign gave both the Japanese and the KMT a much clearer picture of the CPC’s strengths and weaknesses.

Thereafter, the Communists were beleaguered by Japanese sweep operations and Nationalist blockades aimed at containing the party’s sphere of influence. The Red Army suffered devastating losses in the New Fourth Army Incident of January 1941, when Communist forces in southern Anhui province in Central China—then in the process of withdrawing north of the Yangtze River on Chiang’s orders—were surrounded and attacked by Nationalist forces. Meanwhile, the rapid expansion of the party’s membership had opened the door to ideologically “impure elements.” The CPC’s base area was descending into chaos.

In an effort to bring the situation quickly under control, the party leadership launched massive reforms. In addition to the Rectification Campaign, designed to restore ideological discipline, the party undertook to boost productivity through administrative streamlining and greater dependence on rural militias. These decisive reforms enabled the Communists to overcome the crisis of the early 1940s.

In 1942 the Imperial Japanese Army, which was losing ground in the Pacific, began transferring its crack units from China to other key battlegrounds. The thinning and weakening of Japanese forces in China had the biggest impact in the outlying regions, where the Communists were strongest. Under Operation Ichi-Go, carried out in 1944, Japanese forces pushed relentlessly southward through China, smashing the KMT’s National Revolutionary Army as they went, thus creating a military vacuum. Taking advantage of these openings, the Communists switched to an offensive posture and extended their control along the railroads and into the smaller cities. By the time the war ended, the CPC’s base encompassed a population of more than 100 million and its army was 1.27 million strong.

Impact of the Soviet-Japanese War

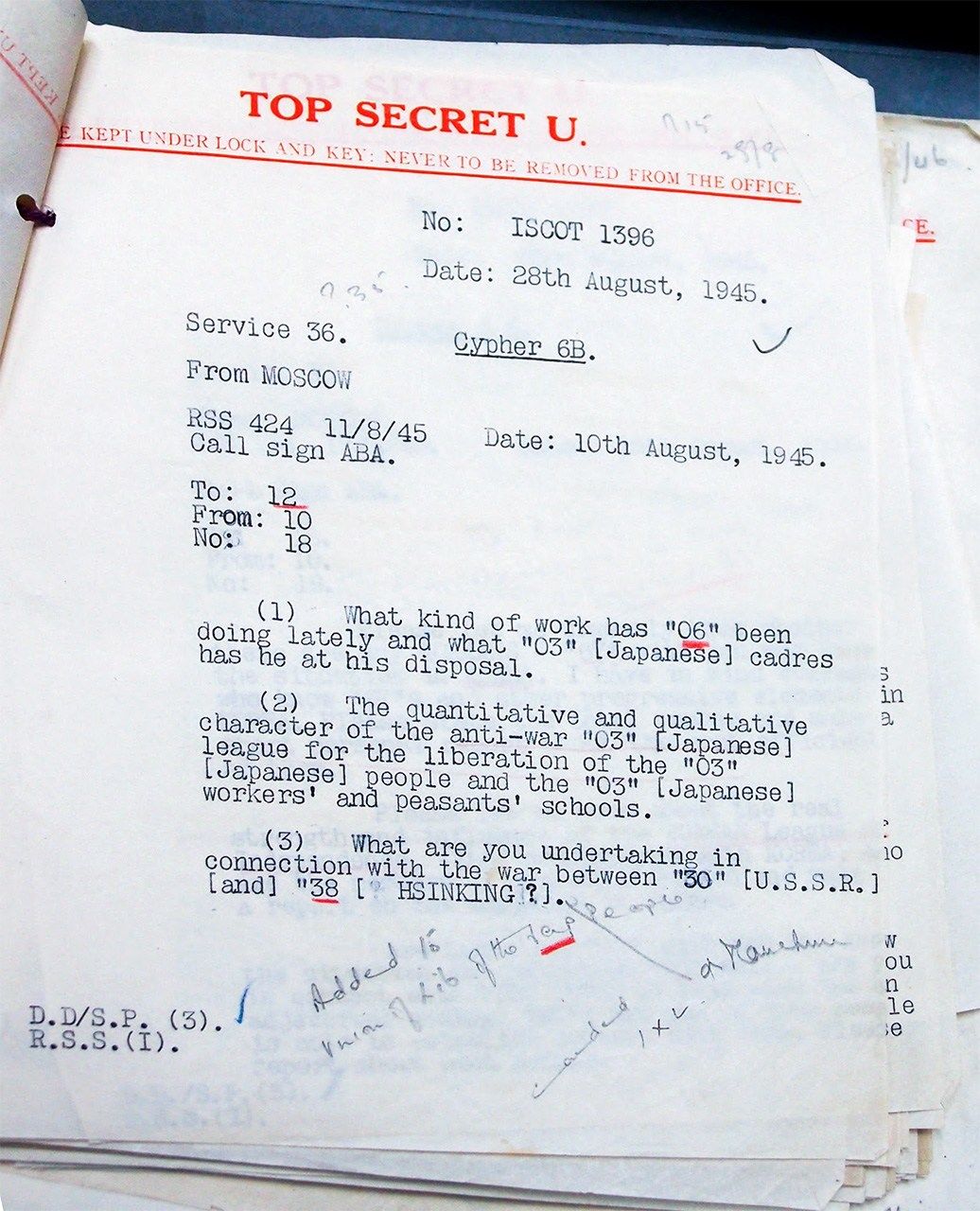

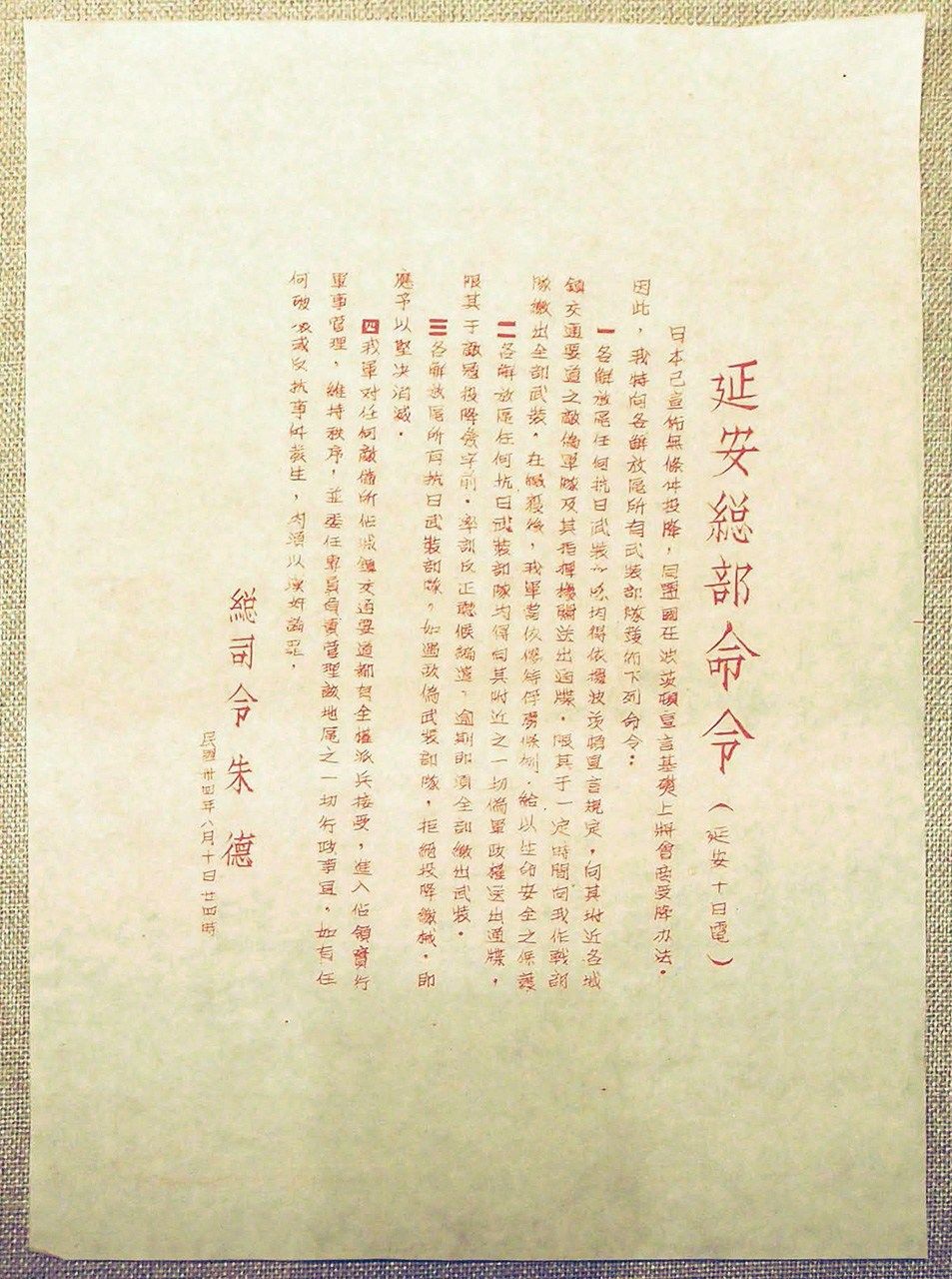

During the final stages of the war, the Communists began to shift from a strategy of dispersed guerilla warfare to one of open combat by large, concentrated forces as it prepared to resume its struggle against the KMT. In April 1945, in anticipation of the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan, the CPC leadership in Yan’an issued instructions to prepare for Soviet operations against Japan and the reversion of the Northeast (Manchuria) to Chinese control. A communication issued on August 10 called for immediate disarmament of Japanese forces and the occupation of cities and transportation in the increasingly likely event of a Japanese surrender. The following day, party headquarters instructed the Red Army to advance into the Northeast. During this crucial period, the CPC—thanks in large part to the support and protection of the Soviet Union—was able to establish a firm foothold in the Northeast. After the civil war resumed, it was able to advance and extend its territory from north to south, eventually taking full control in 1949.

An intercepted encoded telegram sent from Moscow to the CPC on August 10, 1945, inquiring into the situation in Yan’an. (HW/17/42, UK National Archives, Kew, London)

Written orders from the CPC’s Yan’an headquarters, dated August 10, 1945, containing instructions for the disarmament of Japanese forces upon Japan’s surrender. (National Museum of China; photo by the author)

As the foregoing makes clear, the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War marked a turning point for the CPC, allowing it to recover and revive its fortunes after devastating setbacks had left it struggling for survival in the remote Northwest. Unlike the tales of glory and heroism propagated by the CPC’s official historians, this version illuminates the strokes of luck and accidents of history that facilitated the party’s resurgence. At the same time, it acknowledges the strategic leadership that allowed the party to seize and capitalize on such opportunities. Although my version of events may be less glamorous than the official accounts, it is nonetheless a story of great struggle ending in great success.

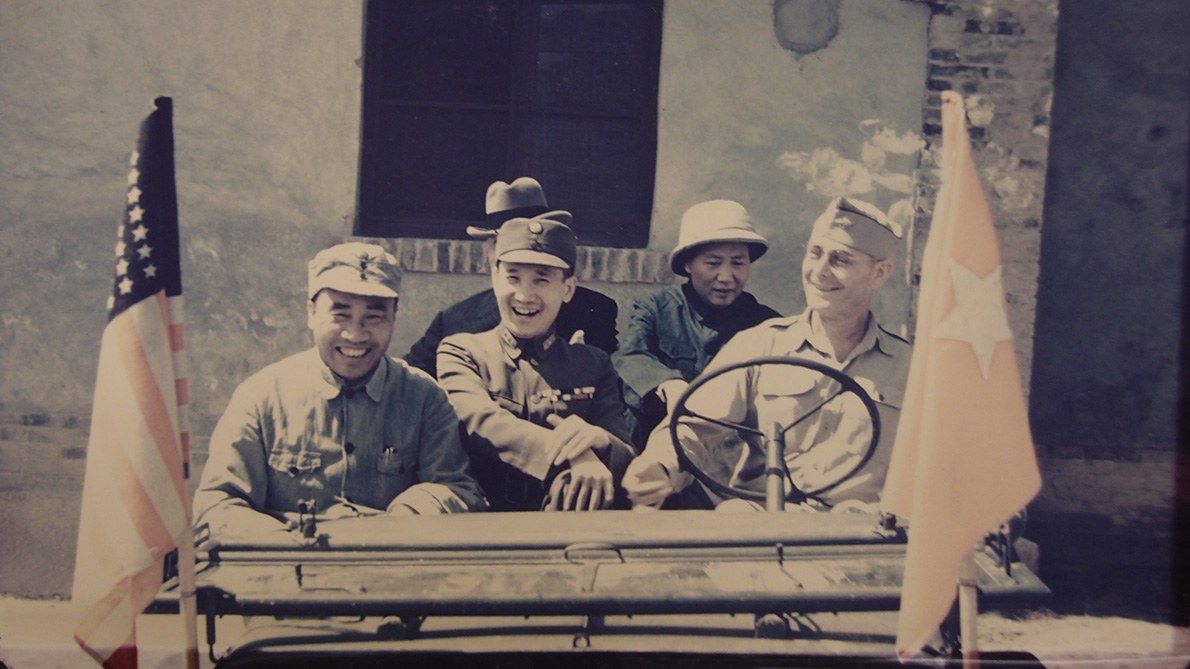

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Mao Zedong and other Chinese leaders in the company of the US ambassador to China in August 1945. In the front seat, from left, are Red Army Commander Zhu De, KMT defense official Zhang Zhizhong, and US Army Colonel Ivan Yeaton; in the rear, seated to the left of Mao, is Ambassador Patrick Hurley, who tried unsuccessfully to reconcile the Communists and Nationalists. Ivan D. Yeaton Papers, Box 9, Hoover Institution, Stanford.)