Economic Security in the Era of US-China Rivalry

Economy Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

What Is Economic Security?

Economic security policy has become a subject of intense focus in recent years, and particularly in the wake of supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In Japan, the challenge of economic security is compounded by rising economic tensions between our ally, the United States, and our biggest trading partner, China. Yet public discourse on the topic reveals a disturbing lack of clarity regarding the scope and content of a rational economic security policy.

Economic security refers to the economic side of national security, which is the protection of the people’s lives and property from any threats. That means ensuring a steady supply of vital goods (food, energy, and pharmaceuticals, and so forth), which in turn depends on such factors as the reliability of supply chains, the stability of business entities responsible for critical infrastructure, and protection from interference or disruption by bad actors, especially hostile foreign powers. It also encompasses the regulation of trade and investment to prevent such actors from obtaining sensitive technology or information that could jeopardize international peace.

Given this broad scope and the wide range of individuals and entities involved, there is a real potential for abuse of the concept of economic security to justify rampant government intervention in private business. It is vital that we approach economic security policy rationally and judiciously to avoid the kind of excessive regulation that stunts economic growth or the sort of arbitrary intervention that reduces predictability and raises the risks of investment, trade, and other business activity. Unfortunately, such a rational, judicious approach is precisely what has been lacking in Japan.

Understanding FDI Oversight

One prominent focus of economic security policy is the regulation of foreign investment in sensitive domestic industries. In 2020, the National Diet passed a revision of the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act that strengthens government oversight of inward foreign direct investment. Specifically, it requires notification to the relevant ministries whenever a purchase of stock in a company in possession of sensitive technology would give a foreign investor (including all its subsidiaries, affiliates, and other related entities) a 1% or larger share. The aim is to prevent foreign interests from obtaining sensitive technology by gaining a controlling interest.

The US government has exercised this sort of oversight for some time via the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, expanded the jurisdiction of CFIUS and beefed up the review process. The countries of Europe have adopted comparable statutes aimed at tightening oversight to prevent foreign direct investment targeting sensitive technology.

Unfortunately, in Japan, a country known for cozy and sometimes collusive relationships between industry and government, there is cause for concern that these new powers will be used to limit the rights of foreign investors, even when they pose no security threat. A recent report concluded that in 2020, METI intervened on behalf of Toshiba’s top management to block proposals by overseas-based activist shareholders, citing the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Control Act. METI’s rationale was that averting the break-up of a company like Toshiba was a matter of national security—a gross misunderstanding of the purpose of economic security policy.

Understanding Supply Chain Security

In recent months, public discourse on the subject of supply chains has also revealed serious misunderstanding. The basic goal, from the standpoint of economic security, is ensuring a stable supply of all goods deemed vital to the nation’s economic activity and the protection of life and property. The ultimate protection from global disruptions in the supply chain would be domestic production of all essential goods, but this is simply not a realistic option. Sound economic security policy involves strategic judgment, weighing the relative merits of domestic and overseas production on an item-by-item basis.

Unfortunately, in Japan such judgment is all too easily swayed by public sentiment and the circumstances of the moment. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, disruptions in the supply chain led to a shortage of disposable face masks and other personal protective equipment, most of which is manufactured overseas. For a brief time, the price of masks soared amid fierce buyer competition over limited supplies. Prices eventually settled down, thanks to the use of cloth masks and other adjustments, but the temporary shortage spurred calls for a wholesale shift to domestic production.

The problem is that the manufacture of low-value-added, mass-produced goods like face masks is economically unsustainable in a country like Japan, where labor and other production costs are relatively high. Domestic manufacturers might be able to operate at a profit in the midst of a pandemic, but once global supply stabilized and prices fell, they would find themselves unable to compete with products made more cheaply in places like China.

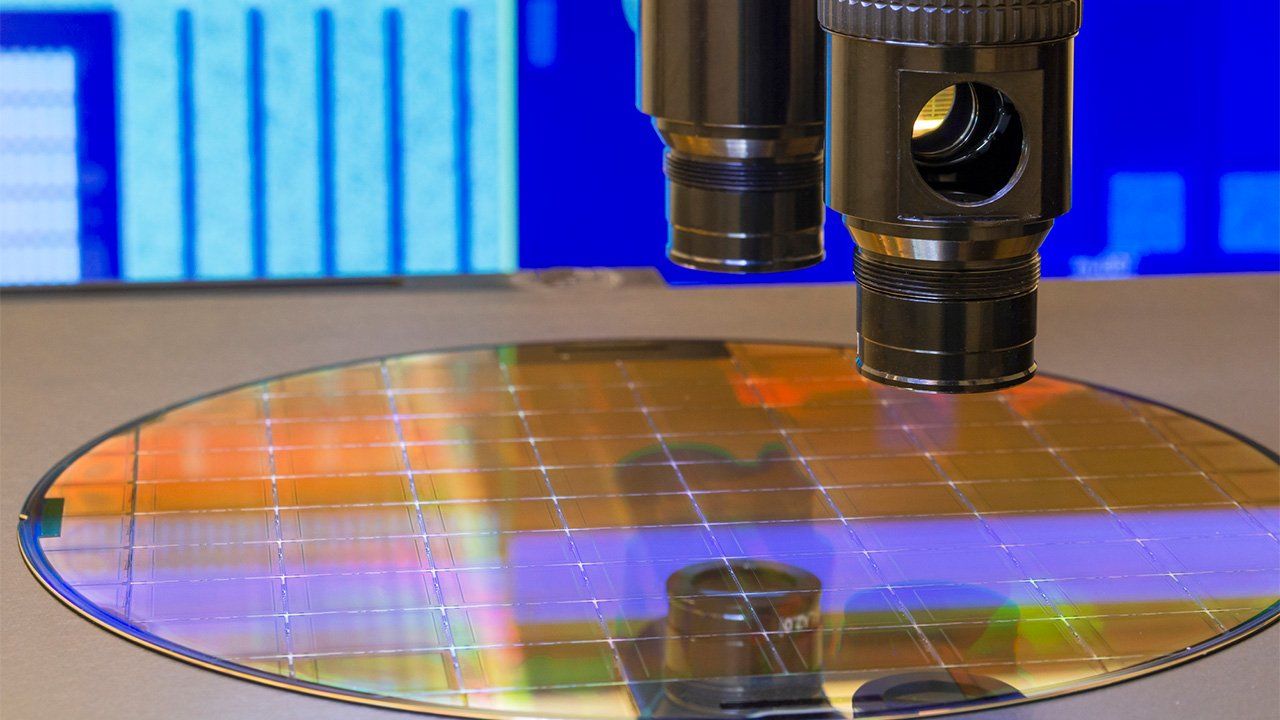

Similar misunderstandings are apparent in recent debates over semiconductors. The semiconductor industry is globally integrated, with a high degree of regional specialization. Chip design and production of advanced materials is heavily concentrated in a few industrially advanced countries, but lower-value-added processes that nonetheless involve considerable investment are difficult to sustain in regions with high production costs and have thus been offshored to companies located overseas, such as Taiwan’s TSMC. In this way, the semiconductor supply chain has become internationally dispersed. Given this division of labor, the call for 100% “made in Japan” semiconductors is simply unrealistic. Nor is a dedicated semiconductor foundry like TSMC likely to respond to inducements to build a fabrication plant in Japan, given that none of its biggest clients are currently located here.

Global supply chain security is a complex matter involving a patchwork of calibrated approaches. For products like disposable face masks, which cannot be produced domestically at a profit, it may involve a combination of stockpiling, diversification of supply sources, and building of emergency production capacity. For goods like semiconductors, which depend on a global division of labor, it is vital that Japan make itself indispensable by controlling a choke point in the supply chain. And the best way it can do that is by specializing in areas where it is internationally competitive, such as advanced materials and production equipment.

In short, economic security does not mean producing all essential goods domestically. In some cases, the government may opt to subsidize an industry for this purpose, as through direct purchases. But the decision must be based on a cool-headed calculation of the item’s strategic importance balanced against the costs of domestic production.

Economic Security and the US-China Rivalry

Economic security has become an especially challenging issue for Japan amid the intensifying economic and technological rivalry between the United States and China.

The administration of US President Joe Biden has called for a review of US supply chains in the areas of semiconductors, large-capacity batteries, rare earth elements, and pharmaceuticals with a view to reducing reliance on China.

China’s rapid technological progress is exacerbating friction with the United States, which views it as a threat to US supremacy. China is relying heavily on high tech to overcome structural obstacles to ongoing economic expansion, including wage increases stemming from economic growth and the decline in the working-age population as a consequence of the old one-child policy. New conflicts continue to emerge as each country strives to protect and promote its own technologies in a struggle for competitive advantage.

The US Department of Commerce continues to add Chinese companies to its Entities List of persons and organizations subject to export restrictions on security or other grounds. Japanese companies that do business with those entities could be shut out of the US market. In response, China has enacted its own law designed to shut out companies that comply with US sanctions. Caught between its military ally, America, and its largest trading partner, China, Japan is facing some tough choices.

What sort of strategy should Japan pursue to protect its economic security amid these escalating tensions?

The first step is to agree on a definition of economic security, including clear criteria for the identification of goods, services, and activities essential to the nation’s economic life. Such clarity is needed both to identify risks and to guard against unfettered government intervention in the name of economic security.

The second step is to hammer out concrete strategies for supply chain security and the control of technology with respect to items of vital importance to the nation’s economy. The Japanese government’s latest Growth Strategy and Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform, both adopted by the cabinet in June 2021, include specific measures pertaining to vaccines and semiconductors, but there are other essential goods to consider as well. The government needs detailed, up-to-date information and analyses regarding the structure of our domestic and global supply chains for all vital goods and a clear strategy for ensuring their stable supply.

Third, we need to establish a centralized, interagency apparatus for the development of supply-chain strategies. To be sure, the National Security Secretariat now has its own dedicated economic team, but that unit has its hands full coping with day-to-day challenges; it is not equipped to formulate long-term strategies for each industry. Members of the NSS’s economic team could provide the nucleus for a cross-government body staffed with experts not just from METI but also from the ministries of Health, Labor, and Welfare (for pharmaceuticals), Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism (for rare earth elements), and Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (for food security).

The time has come to build a comprehensive national economic security strategy that capitalizes on Japan’s strengths to ensure our survival in the era of US-China rivalry and beyond.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: © Pixta.)