Kishida’s Farsighted Plan to Keep Abe in Check

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Prime Minister Kishida Shakes Up Nagatachō

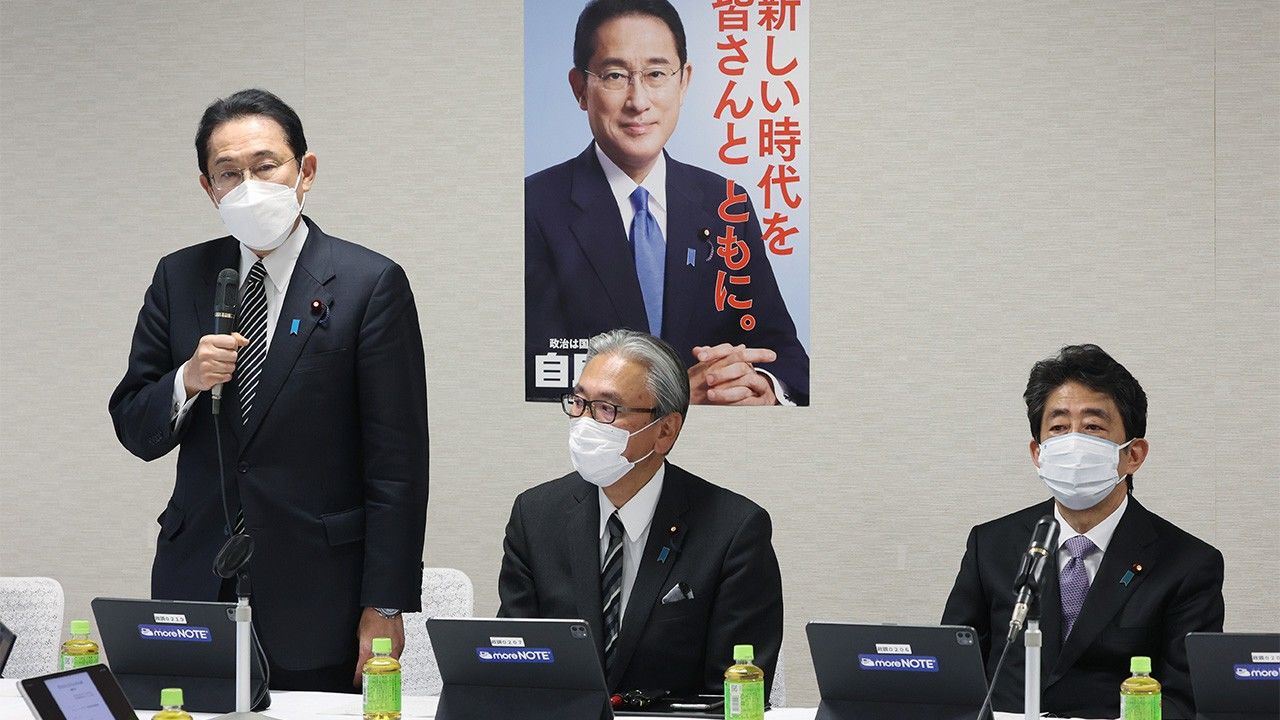

With the passage of a massive supplementary budget assured, the 2021 extraordinary Diet session was winding down. Then, on December 21, one seemingly modest act by the prime minister made the political world sit up and take notice. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio showed up at his Liberal Democratic Party’s headquarters for the first postelection meeting of the Headquarters for the Promotion of Constitutional Reform, now renamed the Headquarters for the Realization of Constitutional Reform.

In the past, it was generally considered taboo for a prime minister to openly discuss constitutional revision. After all, Japan’s leader is obligated to abide by the current constitution. However, most Japanese prime ministers have also been the president of the LDP, a party that since its inception has been committed to the realization of a “self-made” basic law for Japan. Even as the line between prime minister and ruling party president blurred over time, though, it nevertheless remained unusual for the prime minister to attend meetings of the kind Kishida did on that day. Furthermore, Prime Minister Kishida himself had never previously appeared to take much interest in the issue of constitutional revision. For these two reasons alone, his attendance was a surprise for participants.

Surprising too, was the strong tenor of the speech Kishida gave. The prime minister enthusiastically highlighted the contemporary importance of the four proposed constitutional amendments officially settled on by the LDP, which include new provisions allowing the government to exercise emergency powers and an addition to the war-renouncing Article 9 to clarify the constitutionality of the Self-Defense Forces. Kishida said carrying out thorough debate in the Diet and gaining the public’s support were the “two wheels of a cart” for moving forward on constitutional revision, but that he was nevertheless determined to make rapid progress towards revision “by mobilizing the full power of the party.”

The meeting was attended by top party leaders, including LDP Vice President Asō Tarō, Secretary General Motegi Toshimitsu, and former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō. It must have been a particularly satisfying speech for Abe to listen to, given his long-standing desire to see revision of Japan’s constitution.

Constitutional Revision as Kishida’s “Abe Insurance”?

What is behind Prime Minister Kishida’s sudden enthusiastic embrace of constitutional revision? Kishida likely calculates that as long as he advocates for and makes progress on constitutional reform, his administration is less likely to be undermined by Abe, who still wields significant power in the ruling party.

The prevailing assumption in Nagatachō is that the relationship between Kishida and Abe deteriorated soon after the October 2021 House of Representatives election. Kishida appeared to distance himself from Abe and went as far as publicly announcing the disposal of “Abenomasks,” widely acknowledged as a major public relations blunder that critically wounded the Abe administration in early 2020.

However, the actual situation may not be so straightforward. The prime minister is well aware that, if he alienates Abe, the foundation of his own political power could crumble. Even though Abe resigned from the premiership in 2020, he became the leader of the Seiwakai faction, the LDP’s largest, in late 2021. In this position Abe’s voice and influence within the party have only become more powerful.

A closer look at recent events will make clear Kishida’s motivations for managing Abe’s political influence.

Reports of the deteriorating relations emerged in the aftermath of the House of Representatives election. One-time Abe ally Amari Akira, having failed to win his Kanagawa constituency seat (but making it into the lower house in the proportional representation bloc vote), duly offered his resignation as LDP secretary general. Kishida took charge of party and cabinet appointments and chose Motegi Toshimitsu, then minister for foreign affairs, as Amari’s successor.

However, Kishida’s choice to replace Motegi as foreign minister, Hayashi Yoshimasa, represented a major development. Hayashi belongs to the same Kōchikai faction as Kishida. Long regarded a potential future prime minister, Hayashi is also well known to be favorable to Beijing. Indeed, Hayashi began serving as the chairman of the Japan-China Parliamentary Friendship Association in 2017, and only resigned this post following his ministerial appointment to “avoid unnecessary misunderstandings.” Hayashi’s diplomatic instincts therefore greatly differ from Abe, who favors a tougher approach to China.

Kishida’s Chinese Achilles’ Heel

Kishida’s own disposition toward China may also be his Achilles’ heel. Hayashi’s appointment only compounded already deep concerns in the LDP that Kishida is too accommodating of Japan’s giant neighbor.

A recent example of this is Kishida’s prevarication over how the Japanese government would handle the issue of a diplomatic boycott of this February’s Winter Olympics and Paralympics in Beijing. Kishida is surely aware that one wrong move on China policy could quickly lead to his downfall.

The issue with the Hayashi appointment, however, runs deeper than simple misgivings about China policy. Hayashi was elected to the House of Representatives from Yamaguchi Prefecture’s third electoral district, which neighbors Abe’s fourth district. In the past, Abe’s father, Shintarō, a former foreign minister, and Hayashi’s father, Yoshirō, a former finance minister, fought many fierce electoral battles in Abe’s current district.

This personal enmity is likely to be exacerbated in the future by changing electoral boundaries. In order to correct the vote-value disparity, Yamaguchi Prefecture will likely see a reduction in the number of its House of Representatives electoral districts from four to three before the next election. Hayashi is also a relative newcomer to the House of Representatives, after spending many years in the House of Councillors. He made the move to run in last October’s election, anticipating that it would be much harder to make the jump and compete for a lower house seat following the reduction of Yamaguchi’s parliamentary allotment. The next election will, therefore, likely see Abe, Hayashi, and four other LDP incumbents competing for three constituency seats.

Hayashi’s appointment as foreign minister potentially represents Kishida positioning him as a presumptive leader in waiting. Abe was informed in advance of Kishida’s intention to tap Hayashi, and although he expressed strong opposition, Kishida went through with the appointment anyway. It would be hard for Abe to see this as anything but a provocation.

Kishida had also already resisted Abe’s pressure on other appointments. Following Kishida’s selection as LDP president and endorsement as prime minster, Abe recommended that the new leader appoint Takaichi Sanae to the role of LDP secretary general, the number-two party position, and Hagiuda Kōichi to the critical role of chief cabinet secretary. Kishida instead appointed Takaichi and Hagiuda to the lesser roles of chair of the LDP Policy Research Council and minister of economy, trade, and industry, respectively. Hayashi’s appointment, therefore, appeared to underline Kishida’s willingness to resist Abe’s pressure after a better-than-expected lower house electoral performance, instantly stimulating Nagatachō rumors that Kishida was actively distancing himself from Abe.

Does Kishida’s Dovish Image Help Constitutional Revision?

Prime Minister Kishida’s sudden enthusiasm for pushing forward on constitutional revision should be understood in the context of these tensions. Focusing on amendment could well be a powerful tool that helps the Kishida administration preside over greater-than-expected political peace given Abe and other party conservatives’ interest in revision.

I once heard from a senior LDP official that when then Prime Minister Abe appointed former LDP President Tanigaki Sadakazu to the role of secretary general in September 2014, he may have been positioning Tanigaki to be his successor. This source explained that Abe made this unusual move because he was aware that constitutional revision on his watch would be strongly resisted by the opposition due to Abe’s hawkish reputation. Abe was likely calculating that, if he was unable to realize constitutional revision himself, perhaps someone with a dovish reputation like Tanigaki would have greater success in dealing with the opposition parties, who essentially need to sign off on a constitutional resolution before a public referendum can take place.

Tanigaki later retired from politics due to a serious bicycle accident. Abe soon began eyeing Kishida, another member of the Kōichikai, as a potential successor. At the time Abe was also having trouble identifying a single successor from within his own Seiwakai faction.

Abe showed awareness of this calculation in a recent television appearance. “More than anything,” he said, “I want to achieve constitutional revision. The opposition parties refused to discuss constitutional reform during my own administration. I think the Kishida administration, with takes a relatively more liberal stance, may have better chances in achieving this. I would of course provide backup support.”

Abe’s Grandfather and Kōchikai’s Origins

Needless to say, Abe is probably entertaining thoughts other than cold, pragmatic calculations.

It is important to remember that the Kōichikai was founded by Prime Minister Ikeda Hayato. Ikeda was an understudy of Yoshida Shigeru, Japan’s most prominent prime minister immediately after the end of World War II. Abe’s grandfather, Kishi Nobusuke, was a political rival of both Yoshida and Ikeda. While Kishi made constitutional revision his primary political goal, Yoshida and Ikeda instead prioritized economic growth and resisted constitutional change throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Abe appears to harbor an enduring grudge against opposition parties, some newspapers, and the Kōichikai for interfering with his grandfather’s ambitions. That the current standard-bearer of the Kōichikai, Prime Minister Kishida, has been maneuvered into flying the flag for revision is likely immensely satisfying for Abe.

However, leaving aside the issue of whether such personal feelings should be influencing discussion of amending the constitution—the foundation of government—pursuing revision could be of great benefit to Prime Minister Kishida as well as Abe. This is because Kishida was likely also motivated to promote revision in response to the reemergence of the Nippon Ishin no Kai (Japan Restoration Association). Ishin gained a large number of seats in the 2021 House of Representatives election and has since aggressively promoted revising the basic law, even calling for a constitutional referendum to be held at the same time as the July 2022 House of Councillors election. Ishin has also criticized the prime minister for lacking reform spirit in general, and will keep up pressure on Kishida and the LDP by aligning with Abe and his allies. Emphasizing constitutional reform therefore removes this avenue for attack.

The question remains as to what parts of the constitution Kishida will target for revision. It will also, of course, not be easy to reconcile the opinions of the various parties going forward. Nevertheless, if the interests of Prime Minister Kishida and Abe remain aligned on this issue, constitutional reform debate is likely to take on a new urgency.

If Kishida can survive this year’s House of Councillors election and achieve constitutional revision—which even the long-lasting Abe administration failed to achieve—his administration has a chance of remaining in power for some time. Recent developments outlined here suggest that even Prime Minister Kishida has begun to harbor such ambitions.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, at left, addresses a meeting of the LDP’s Headquarters for the Realization of Constitutional Reform. In the center is the group’s chair Furuya Keiji, and on the right is former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō. Taken at LDP Headquarters, Nagatachō, Tokyo, on December 21, 2021. © Jiji.)