Grading Japan’s New High School History Course

Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

New Compulsory Courses

In April 2022, new curriculum guidelines were introduced in Japanese high schools, based on three qualities and abilities to cultivate in students: knowledge and techniques for active use; the ability to think, make judgements, and express oneself in unfamiliar situations; and the ability and humanity to apply what one learns to life and society.

To achieve these aims, more emphasis than ever is being placed upon how students learn, and classes need to be improved to ensure that they are independent, interactive, and in-depth. Criterion-referenced assessment has also been fully introduced in high schools. Instead of assessing students’ ability only through regular examinations, they will be evaluated in three areas: knowledge and techniques; the ability to think, make judgements, and express oneself; and attitude to independent study. The goal is to foster well-balanced academic skills as high school education undergoes great changes.

In line with the changes, there are two compulsory courses for history and geography, called rekishi sōgō, literally “comprehensive history,” and chiri sōgō, or “comprehensive geography.” Rekishi sōgō takes a comprehensive look at Japanese and world history from the eighteenth century to today, but it is not simply a combination of the former courses World History A and Japanese History A, which focused mainly on the modern and contemporary eras.

Historical topics since the eighteenth century are divided into three areas: modernization, changes in the global order and the rise of popular society, and globalization. From these perspectives, students examine the formation of contemporary issues including those related to the environment and resources, poverty, conflict, and gender, along with their proposed solutions. The course aims to help students understand the issues that we face, which need to be tackled through global initiatives, both in their essentials and as matters concerning themselves.

Changing Study Methods

The study method does not follow an exhaustive chronological approach to historical events. The Courses of Study guidelines emphasize understanding historical periods and transitions through cause and effect and other associations, using multiple perspectives and opinions as a basis for consideration, and encouraging students to develop their knowledge into broader concepts.

For example, to encourage active learning on the topic of modernization, students use materials and what they have learned already to present questions based on what they wish to investigate. Classes are structured so they can then pursue these questions. They can adopt various perspectives through use of the materials to consider related contemporary issues, such as environmental problems.

While teachers have expressed various concerns and doubts about the change in study style, they have also offered diverse forward-thinking proposals. Concerned about how many students dislike history as a subject centered on memorization or simply show no interest, many researchers and teachers have held study groups and published books targeting a revolution in history education in Japan. There are also websites for sharing printouts to use in class.

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology is working to disseminate information about the rekishi sōgō study methods, while local authorities have trained teachers in how to prepare and use materials, along with ways of asking questions. However, schools were struggling to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic over the two years before implementation, as well as the initial introduction of criterion-referenced assessment the year before, meaning not all schools and teachers were thoroughly prepared for the changes this academic year.

Interpretation and Discussion

The changes in the curriculum are being introduced gradually, so this academic year (starting in April 2022) students in their first year of high school study rekishi sōgō, while those in their second and third years continue with the previous course. At many schools, teachers keen to prepare for rekishi sōgō and young instructors are taking on the new course, while veterans teach the former one. This seems to have helped the implementation to get off to a steady start.

In a process of trial and error, teachers are holding classes in which students form groups to exchange information on the study materials, discuss their ideas, and deepen their understanding. Taking the example of the Industrial Revolution, they may see illustrations of women working in factories and children in coal mines, and ask questions about why the women and children are working, whether it was acceptable for the children not to be in school, and what the men were doing.

They may also apply other materials in pursuing these questions, debating and considering matters like what industrialization was and how it changed society. Teachers monitor the discussion, offering extra information to encourage correction of mistaken understanding, so as not to discourage students’ desire to think.

Many textbooks suggest questions for each topic and include substantial materials, such as texts, maps, illustrations, and statistics for considering them. Some no longer use boldface type to highlight key points and may provide reading perspectives rather than explanations under their materials.

I hear that these textbooks and the use of websites for sharing materials have made the transition to the new method of study relatively smooth. As high school students in recent years have group-work experience from their years in elementary and junior high school, they are used to this kind of study, and actually seem to be more comfortable with it than in classes consisting only of lectures.

However, if teachers give explanations of what is correct when discussing historical materials, students will tend to only make a note of what the teachers say, and themselves become less active. It is difficult to find the right balance for lessons.

Nonetheless, apparently many students are finding it motivating and fun to interpret materials and engage in discussions during rekishi sōgō classes. If more teachers take on the compulsory topic for the next academic year, as well as electives on exploring Japanese and world history, forward-thinking practices will spread, along with this new version of history education.

The Entrance Exam Issue

On the other hand, some educators suggest that it remains vital for students to memorize the entire textbook for university entrance examinations. In March 2021, the National Center for University Entrance Examinations announced that the Common Test for University Admissions to be held in January 2025 will have questions covering chiri sōgō and rekishi sōgō.

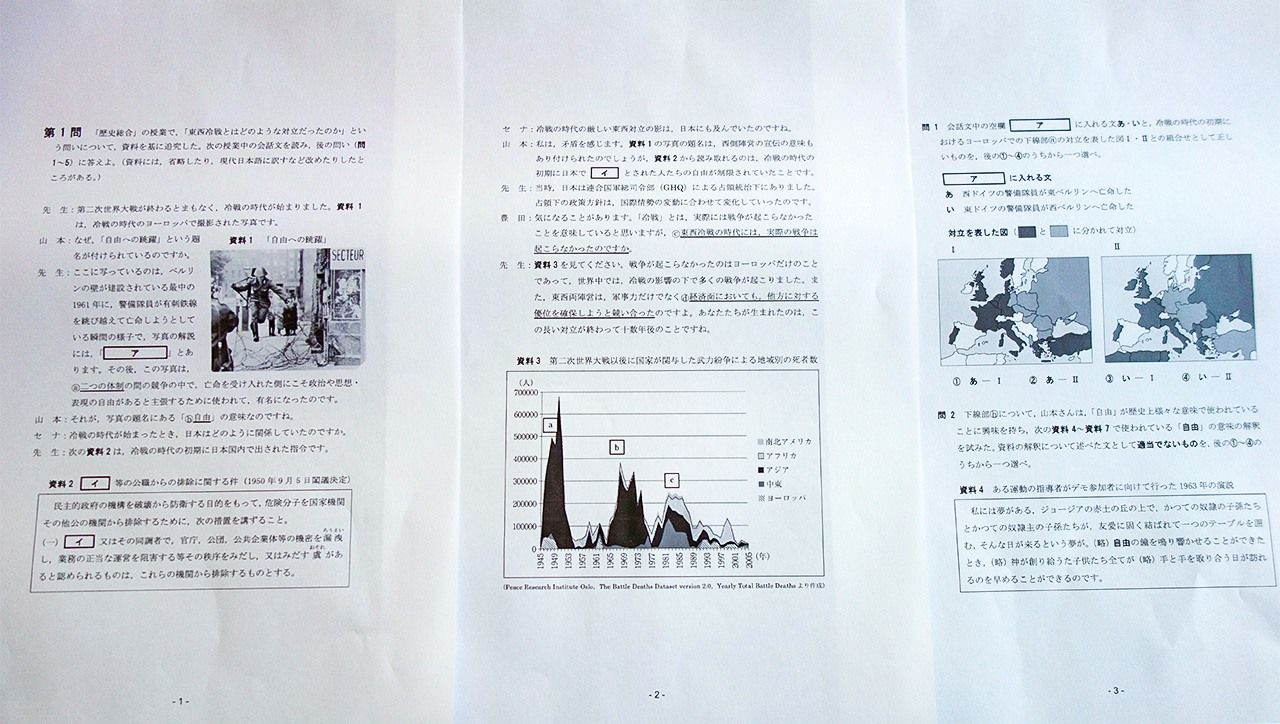

The center has posted sample questions for rekishi sōgō on its website. Judging from these, it seems possible that there will be questions testing students’ ability to examine materials related to the topics of modernization, changes in the global order and the rise of popular society, and globalization.

Sample rekishi sōgō questions published by the National Center for University Entrance Examinations.

However, preparing such questions every year requires considerable effort. Among reports on the first term of teaching rekishi sōgō, some teachers have described making their own questions that students answer by gleaning information on modernization from materials and connecting it to what they already know. Comments on this include, “It’s difficult to create multiple-choice questions that test whether students can understand the concepts they have learned and apply them, or their ability to think and make judgements,” and “If we get them to write an essay, it’s hard to grade it.”

As teachers experience the difficulty of writing questions and evaluating students, there is likely to be more pessimism about changes to entrance examinations, including those for private universities. This will lead to more teachers feeling that they have to focus on drumming what is included in textbooks into students’ heads.

To enhance learning assessment, it is also now required to perceive the process by which students learn. It is necessary to assess, such as by checking off items on a worksheet, how students pose their questions, obtain information from materials, and think. This evaluates both their attitude to independent study and their ability to think, make judgements, and express themselves.

With the burden of assessment piling on top of class preparation, there is a sense of exhaustion in classrooms. After the introduction of electives on exploring Japanese and world history in the 2023–24 academic year, the question of whether new study and assessment methods take root may depend on whether it is possible to develop assessment that is not onerous without relying on questions testing memorization.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 23, 2022. Banner photo: A rekishi sōgō class at Kobe University Secondary School. © Kyōdō.)