Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis: A Chinese Debt Trap?

Politics Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Protests Topple a Government

What comes to mind when you think of Sri Lanka? Possibly you think of tea, curry, and world heritage sites. People who have studied development economics, however, likely recall that Sri Lanka achieved high scores on literacy and life expectancy human development indicators despite a relatively low GDP per capita.

Earlier this year, Sri Lanka was hit by its first economic crisis since independence in 1948. Depleted foreign currency reserves meant Sri Lanka could not bring in essential imports. Sri Lanka relies on imports for 100% of its fuel, and people have endured a major deterioration in their living conditions. They have stood in line for days at gas stations and even begun using wood fuel instead of gas. Fed-up citizens quietly began to take to the streets in March this year.

In April, protesters began to set up tents in central Colombo to continue the antigovernment protests. The protestors do not appear to belong to any particular group, and some have brought along their families, at times giving the protests a festival-like atmosphere. The protests succeeded in forcing President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign in July, a sudden turn of events that would have been hard to imagine at the start of 2022.

After all, President Rajapaksa had won the presidential election in November 2019 with a record number of votes. His prime minister is his brother Mahinda Rajapaksa, regarded by many as a hero for having ended the nearly 30-year civil war with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in 2009 while enhancing Sri Lanka’s economic growth.

Chronology of Sri Lankan Politics

| 2009 | Civil war ends |

| 2010 | President Mahinda Rajapaksa reelected |

| 2015 | Health Minister Maithripala Yapa Sirisena defeats Mahinda Rajapaksa in presidential election |

| 2019 (April) | Parallel bombings at eight locations kill 259 people (Easter Terror Attacks) |

| 2019 (November) | Gotabaya Rajapaksa wins presidential election |

| 2022 (May) | Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa resigns; Ranil Wickremesinghe appointed prime minister |

| 2022 (July) | President Gotabaya Rajapaksa flees Sri Lanka and resigns; Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe becomes president |

Created by Nippon.com.

Plummeting Currency, Foreign Exchange Reserves

How did Sri Lanka, once an honors student in South Asia, end up in such a predicament? Other than commodity exports, Sri Lanka’s main sources of foreign exchange are tourism and remittances from Sri Lankan workers abroad. However, tourism revenues fell sharply due to the COVID-19 pandemic just as tourists were returning to Sri Lanka after the Easter terror attacks of April 2019. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also had an impact, as both Russians and Ukrainians made up a large percentage of tourists to Sri Lanka. Remittances from Sri Lankans working abroad also declined.

No doubt these blows played a role. Sri Lanka, however, is not the only country to suffer a drop in tourist income and remittances. So, why did these events precipitate Sri Lanka’s crisis?

In 2017, Sri Lanka no longer appeared to be able to repay the construction costs of the Hambantota port in the south of the country, and was forced to hand over the lease to operate the port to a China–Sri Lanka joint venture for 99 years. Many saw this as a classic example of Chinese debt-trap diplomacy. Perhaps the current crisis was the result of ballooning debt owed to China.

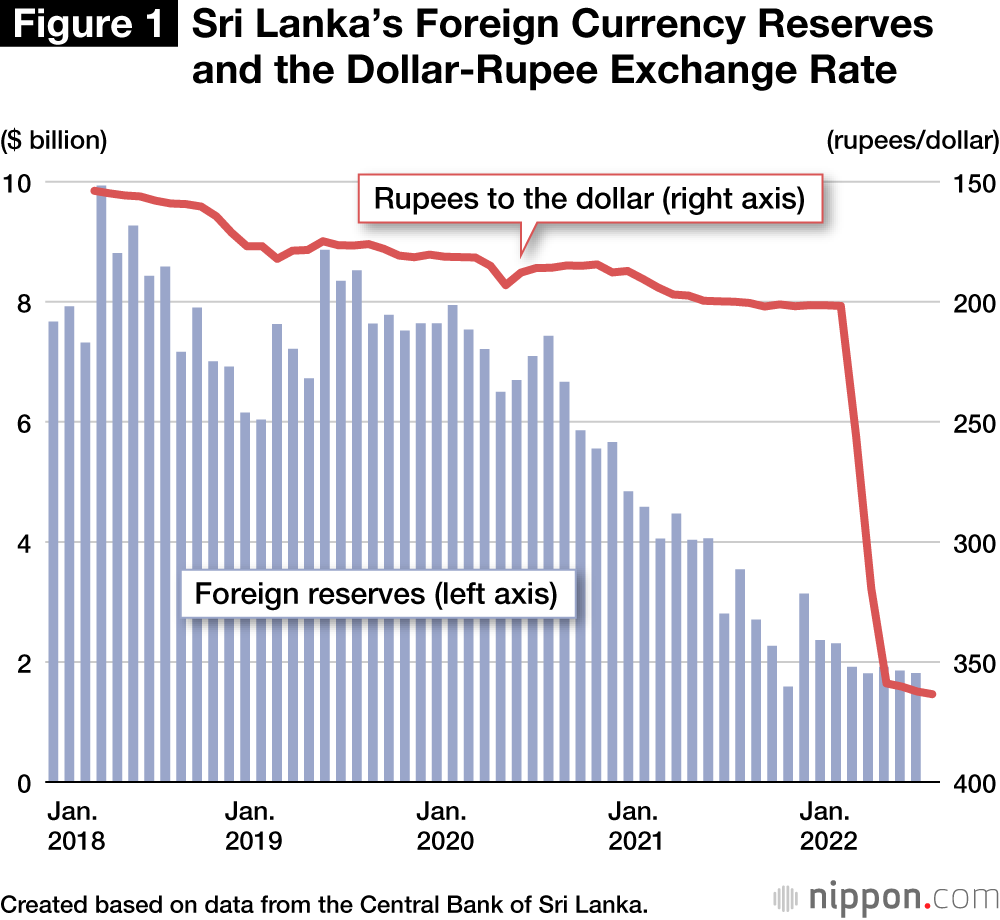

Sri Lanka lacks sufficient foreign currency for paying for imports or debt servicing. Figure 1 below shows that, as of mid-2020, Sri Lanka had reserves sufficient to pay for four to five months of imports. These reserves have only further declined since then, and by the end of 2021 the situation became critical when reserves dropped to the equivalent of only one month of import payments. The government managed to make it to 2022 through currency swaps with India and Bangladesh.

However, the lack of foreign currency reserves undermined confidence in Sri Lanka and made it impossible to open import letters of credit necessary for facilitating imports.

Interestingly, the government had initially managed to maintain the value of the Sri Lankan rupee despite the rapid depletion of foreign exchange reserves. The central bank, however, stopped buying the rupee in March. The exchange rate quickly dropped to 255 rupees to the dollar and continued its fall to over 350 rupees in June.

Increased Borrowing in International Financial Markets

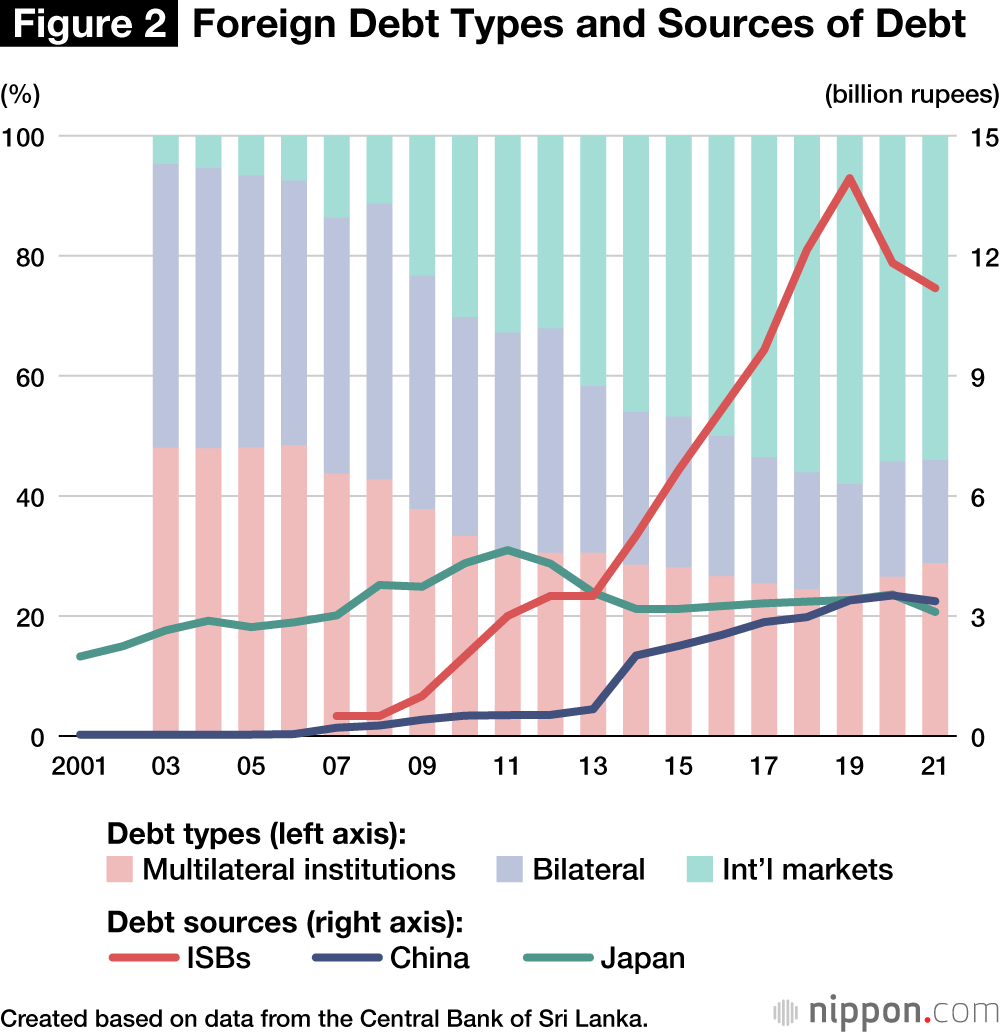

Figure 2 shows the extent of Sri Lanka’s external debt. Borrowing from multilateral financial institutions and bilateral sources accounted for more than 90% of the government’s external debt up until 2007. That year, the Sri Lankan government issued its first international sovereign bond in the international financial markets, obtaining $500 million. Sri Lanka continued issuing ISBs, and by 2021 the majority of its external debt was sourced from international financial markets.

Sri Lanka’s borrowing from China, which includes financing from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China, only comes to about 10% of the total of the country’s international debt, which is about the same level as Japan. Even including loans for state-owned enterprises and other government-backed financing, China’s share of Sri Lankan debt still only comes to around 20%. The biggest financial burden on the Sri Lankan government is not borrowing from China but the need to repay ISBs, which account for about 35% of the country’s external debt.

Sri Lanka began to raise ISBs from international financial markets because if a foreign country wants to implement a project in Sri Lanka, it is required to provide 30% of the funds. Initially, the government only issued $500 million to $1 billion of bonds every few years. However, as ISBs can be raised more quickly and on looser terms than borrowing from multilateral institutions or through bilateral negotiations, the Sri Lankan government increased the amount and frequency of ISB issuance. The disadvantages to this approach are higher debt servicing costs and the need to repay loans in lump sums every 5 to 10 years.

Infrastructure Development Financed by China

Is borrowing from China connected to the issuance of ISBs? The Rajapaksa administrations cultivated close relations with China beginning in the mid-2000s, which led to numerous infrastructure projects being implemented by China. Between 1971 and 2012, China provided some $50 million in aid and loans to Sri Lanka, 94% of which came after Mahinda Rajapaksa became president in 2005. Only 2% of this figure was in the form of grants, while the rest consisted of concessional loans. Construction of the Hambantota Port then began in 2007, and both the Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport and Colombo South Container Terminal were completed in 2013.

Many have noted the strong ties between China and the Rajapaksa administrations underpinning these projects and have questioned their necessity, given that the facilities built have not been fully utilized. However, despite the fall of the pro-China Rajapaksa administration in 2015, the issuance of ISBs continued even under the new government promising a more balanced approach to regional diplomacy. In fact, the amount increased during the period of that government (January 2015 to November 2019).

As a result, for the 2019–21period, Sri Lanka’s external debt repayment obligations amounted to about $4 billion, about half being attributable to ISB repayments. The reason why the central bank tried to maintain the dollar-rupee rate at around 200 rupees despite the rapid depletion of foreign exchange reserves (see Figure 1) is likely that it feared import inflation as well as the ballooning of dollar-denominated debt repayments.

The repayment schedule for external debt was fixed, and the government knew in advance that repayment would be burdensome. One option raised in early 2021 was to take out a loan from the International Monetary Fund. However, the central bank governor at the time rejected this option possibly due to the strict conditionality associated with IMF loans. Implementing the IMF’s requirements would likely have placed a huge burden on the public. The government instead prioritized maintaining Sri Lanka’s creditworthiness in international markets by continuing timely repayment of ISB and other debts. However, the Sri Lankan economy was soon in rapid decline, rendering irrelevant the government’s concern about its financial reputation and conditionalities.

A Fragile Economic Structure

If China is not the direct cause of the economic crisis that brought down the president and forced him to flee the country, what is? A succession of troubling events such as the 2019 Easter terror attacks, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have all had an impact. The Gotabaya administration’s tax cuts and agricultural policy failures are also responsible. However, problems with Sri Lanka’s overall financial and economic policies are also major contributors to Sri Lanka’s current situation.

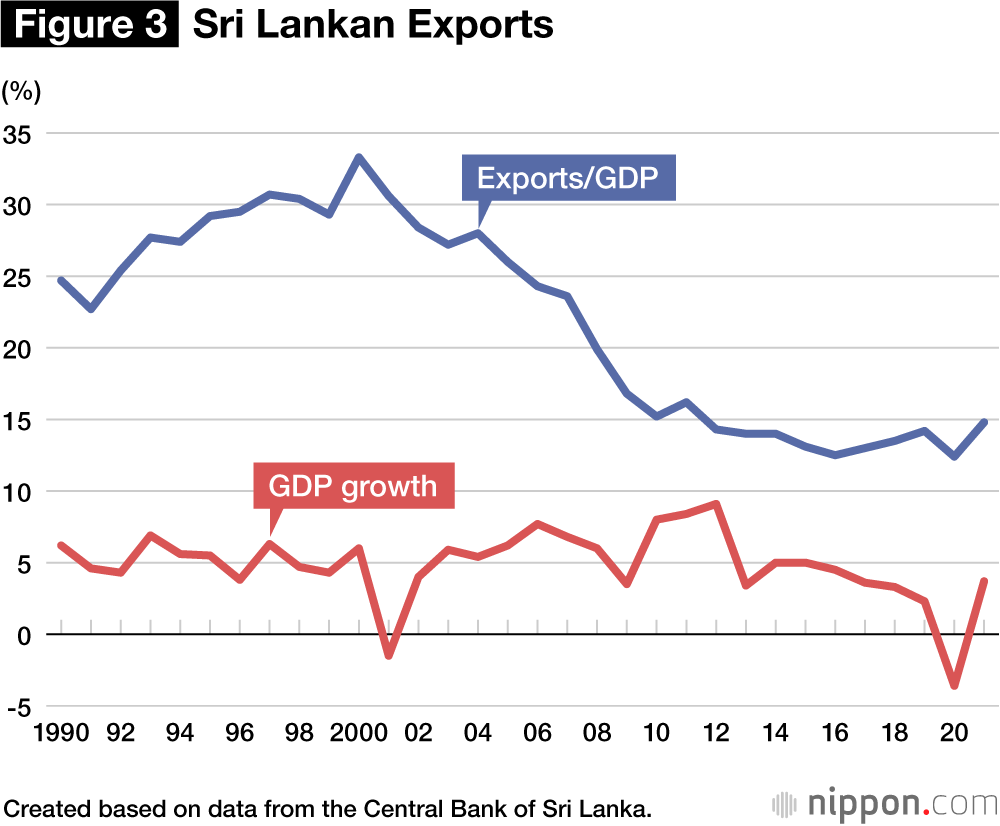

First, the government knew that repaying foreign loans required the accumulation of foreign currency. Sri Lanka’s main sources of foreign currency come from exports, tourism, and remittances from Sri Lankan workers abroad. However, Sri Lanka’s ratio of exports to GDP, which was just 33.3% in 2000 (Figure 3), has only continued to decline.

If Sri Lanka enjoyed a positive net export balance due a low level of imports, then exports being a small percentage of GDP would not be a major problem. However, Sri Lanka relies heavily on imports for raw materials, intermediate goods, and investment goods, and has a persistent trade deficit. Sri Lanka, therefore, has only a small buffer in the event of contingencies that affect tourist income and remittances. The government should have been more active in promoting new industries, enhancing the value-add of existing export industries, and expanding and diversifying export markets.

What Next for the Sri Lankan “Welfare State”?

The next problem is the exchange rate. Normally, the rate should move up and down relative to the scale of exports and imports. However, the Sri Lankan government has attempted to maintain the value of the rupee at a high level against the dollar to keep the prices of imports low. Inflation, after all, functions as a barometer for government support or disapproval.

As the exchange rate remained high, the incentive to reduce imports weakened. In an attempt to lower imports, Sri Lanka did attempt to impose some restrictions, such as a ban on vehicle imports in March 2020. However, it failed to achieve its goals.

As noted in the introduction, Sri Lanka has a reputation as a “welfare state” pursuing policies that have had positive effects on the educational attainment and health of its population. With the current crisis, however, the population may have to reevaluate these benefits, which many have taken for granted. Perhaps a harder line on these benefits is the right economic policy. However, the new Sri Lankan government needs to accept that it will be despised by the population, and its supporters and officials need to accept the role of political villain.

In the late 1970s, China also faced the possibility of depleted foreign exchange reserves. Japan helped by providing a route to transport coal from Shanxi to coastal Shandong Province. China was able to recover its reserves by exporting this coal to Japan. This may sound idealistic now, but it provided the basis of a foreign aid relationship between the two countries.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Supporters rejoice in Colombo after Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister Wickramasinghe is appointed president by the parliament on July 20, 2022. ©AFP/Jiji.)