Constitutional Politics in the Post-Abe Era: Institutional and Political Hurdles

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Introduction

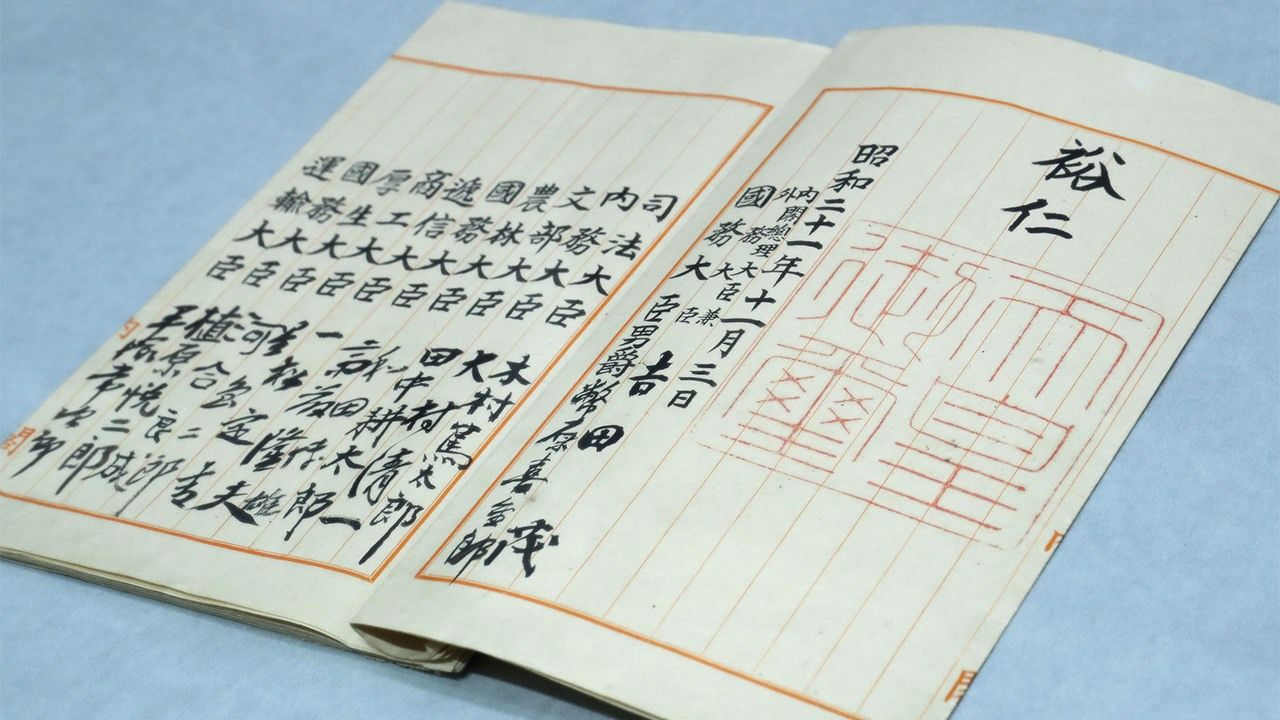

Ratified in November 1946 and promulgated in May 1947, the Constitution of Japan is the oldest unamended constitution in the world today. However, its origins and contents have long been controversial. The Constitution was drafted by officers of the Allied Occupation in the aftermath of Japan’s World War II surrender. While it underwent significant revisions during Diet deliberations, critics have decried it as an imposed document that lacks democratic legitimacy.

One of the most earnest proponents of constitutional change in recent years was Abe Shinzō, prime minister in 2006–7 and 2012–20. His Liberal Democratic Party had long made amendments, particularly to the Article 9 “peace clause” that prohibits Japan from using military force or possessing “war potential,” an ideological goal. It had published wholesale amendment proposals in 2005 and 2012, and Abe himself declared in 2017 that “I would like to make 2020 the year that a new constitution is enacted.” While Abe’s initiatives stalled due to intraparty disagreements and political scandals, he continued to push for constitutional change in public speeches, even after his resignation in September 2020 for health reasons.

Abe’s untimely murder in July 2022 during the House of Councillors election campaign restarted debates about amending the Constitution to honor his legacy. This essay argues that the institutional and political hurdles to constitutional change should not be underestimated. First, while pro-amendment parties constitute more than the requisite two-thirds of the Diet, there is disagreement within and between them on how to revise the Constitution. Second, public support for constitutional amendment is fickle, which makes politicians hesitant to stake their electoral survival on a divisive issue. These problems in many ways illuminate Abe’s legacy on constitutional matters: amendments require a leader who is willing to prioritize the issue over other pressing policy priorities.

Step 1: Convincing the Diet

Article 96 outlines the procedure for constitutional amendments. It requires a concrete proposal to first obtain two-thirds approval in both the House of Representatives and House of Councillors, after which it must receive majority support in a national voter referendum. At a global level, this process is fairly standard. Three-quarters of national constitutions today mandate a two-thirds parliamentary hurdle, of which approximately half include additional provisions for a national referendum. However, further details on how it shall be proposed and voted in the Diet, as well as the guidelines for conducting the referendum, are determined in legislative statutes.

The first hurdle for pro-amendment parties in Japan is to secure the necessary seats in the Diet. While much debate has focused on the two-thirds requirement, the legislative process by which amendments must be deliberated also poses strategic restrictions. According to Article 68 of the Diet Act, a concrete amendment must be submitted to the Diet with the sponsorship of 100 representatives or 50 councillors. The proposal is then sent to the Committee on the Constitution of the initiating house, or held jointly by the Houses of Representatives and Councillors, for deliberation, after which it is submitted to each chamber for a vote.

Crucially, each amendment proposal must be on a discrete topic or matter, although there is no explicit standard for distinguishing topics as of yet. In principle, it would not be considered appropriate to submit a single proposal to amend the Article 9 peace clause and add a new right to privacy. The prohibition of an omnibus proposal means that for amendments to receive the necessary two-thirds in both Diet chambers, there must be a single topic on which the necessary number of legislators agree, or there must be a tacit quid pro quo agreement for parties to support each other’s proposals. The LDP has generally opted for the latter tactic. In fact, one of Abe’s achievements on constitutional change was clarifying the party’s aims with an eye toward multiparty agreement.

Leading up to the 2017 general election, Abe and the LDP sharpened their attention on four issues. The first was amending Article 9 to explicitly acknowledge the existence of the Self-Defense Forces. The second was to expand the right to free education to include secondary and tertiary education, which had long been demanded by Nippon Ishin no Kai (Ishin), an opposition party. The third was to guarantee each prefecture at least one seat in the House of Councillors. The fourth was to add a new chapter on “state of emergency” provisions to expand executive branch powers and allow the postponement of general elections during natural disasters, foreign attacks, or domestic disorder.

Abe’s strong push changed the tenor of constitutional debates. During the 2021 House of Representatives election, numerous centrist and right-wing opposition parties, including the Democratic Party for the People and Ishin, made clear they were willing to deliberate amendments after the election. Even the Constitutional Democratic Party, while not in favor of the LDP’s priorities, stated its openness to discuss possible revisions.

That said, parliamentary enthusiasm for revising the Constitution does not equate to agreement on revision priorities. In the 2021 lower house election, no amendment topic had explicit support in the manifestos of more than two parties. At the same time, there remain significant intraparty disputes, including within the LDP on its four amendment goals. Some senior LDP legislators have stated that simply enumerating the SDF is insufficient, preferring instead to revise Article 9’s proscription against military forces altogether. The expansion of education rights is also divisive, as it is expected to cost as much as ¥4 trillion, which is anathema for fiscal conservatives.

One area of potential compromise is the addition of state of emergency, or SOE, provisions, which would allow the state to override certain individual rights and bypass legislative regulations during national crises. The impetus has been the COVID-19 pandemic. The Japanese government’s response was passive by international standards. In stark contrast to countries that closed public transportation and workplaces, the national government could only issue requests or “soft directives” that relied on voluntary compliance with social distancing guidelines, due to constitutional protections of civil liberties such as the freedom of movement. Abe and his successors, Suga Yoshihide and Kishida Fumio, have argued that the Constitution needed to add SOE measures, so that the national government could better coordinate and enforce pandemic responses, including legally enforced stay-at-home and business-closure orders.

Step 2: Convincing Voters

Even should pro-amendment parties agree on a single proposal or tacitly trade votes on a set of amendments, ratifying constitutional changes requires majority support in a national voter referendum. Specific details regarding how such a referendum would be held are detailed in the National Referendum Act. A formal voter referendum, open to all citizens aged 18 or over, must be held between 60 and 180 days of the Diet vote. Voters would cast an up or down ballot on each amendment proposal separately. Proposals that receive more than 50% support would be officially ratified and go into effect after a prescribed period. There is no minimal voter turnout requirement for the referendum to be declared valid.

(As a side note, after the Diet approves amendments, a Council on the Publicization of the National Referendum is to be established, with 10 representatives from each house of the Diet. The Council disseminates information via the media about the content of the amendments, including opinions both in favor and against. Separately, parties, activists, and citizens can campaign on constitutional change. There are fewer regulations on the range and expense of campaigning that is permissible. This is a point of contention for pro-status-quo parties, which have argued that this will permit pro-amendment parties—particularly the wealthier conservatives—to manipulate public opinion unfairly.)

The greatest uncertainty for pro-amendment parties, notably the LDP, Kōmeitō, Ishin, and the DPP, is how their supporters will vote. While Diet members may be able to forge a strategic quid pro quo agreement to support each other’s proposals, there is no guarantee that their voters will fall in line. For example, LDP supporters may vote for a rewritten Article 9 but not the expansion of public education, while Ishin voters may do the opposite. As such, the more straightforward path is to unify behind a single issue.

As of September 2022, the topic with the greatest odds of amendment appears to be the specification of state of emergency provisions, whose salience has risen in the wake of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Public sentiment toward SOEs has become more favorable in the last five years. According to constitutional surveys by the Yomiuri Shimbun in 2017 (when Abe first openly pushed for amendments) and 2021 (after the pandemic was well underway), overall approval for constitutional change rose slightly from 49% to 56%. One key driver appears to be the perceived necessity of enumerating SOE guidelines. Despite some differences in question wording, support for clarifying the obligations and powers of the government during emergencies almost doubled from 31% to 59%.

That said, public approval for SOE provisions may change quite rapidly. While SOE measures are popular, their salience has historically fluctuated with natural disasters. Notably, support for SOEs rose after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami disaster, but gradually waned after a few years. In addition, it is not clear if the national emergency powers envisioned by the LDP, including strengthening the central government’s authority to override civil liberties such as freedoms of movement and assembly, are what voters have in mind. In fact, many citizens may be unaware of the implications of SOE provisions. Surveys typically ask about establishing SOE guidelines in very general terms, without defining concretely how the powers of different actors would change.

Given that both the legislative and voter referendum votes will require exact language, it is necessary to examine support for specific powers and the conditions under which they can be wielded by whom. In December 2020 I designed an original survey to assess attitudes toward emergency provisions in a more granular way, listing seven different extraordinary powers. While a majority of citizens supported national emergency provisions generally, there were no specific powers that a majority preferred. The most popular was restricting the freedom of movement, including legally enforced stay-at-home orders, but its support level was 47.4%, just below a majority. Second was allowing the Cabinet to issue decrees with the same force of law as legislation, but this was only favored by 31.9%. The least popular, at 10.6%, was allowing for general elections to be postponed, which has been one of the priorities of the LDP.

In Conclusion

Collectively, these results point to the fact that citizens may like the concept of national emergency powers, but when shown the concrete changes being deliberated, they do not see them as necessities. Public ambivalence is crucial, because politicians are hesitant to push for reforms that risk electoral backlash. The electoral payoffs from emphasizing constitutionalism is limited, as most centrist, independent voters care more about macroeconomic performance and social welfare. At the same time, many voters need a good reason to amend a constitution that has served the nation well since 1947. This risk aversion is particularly relevant because voters have no reference point for changing the supreme law. Under conditions of high uncertainty, voters are sensitive to who is proposing amendment. Proposals that are perceived as neutral are more popular than those that are seen as LDP-driven, especially among independents and opposition party supporters. It is not yet clear if the LDP and pro-amendment opposition parties, notably DPP and Ishin, can agree on details for SOE provisions to create a multipartisan patina.

Will Abe Shinzō’s death spur legislative action to amend the Constitution of Japan? His tenure as prime minister illuminated the importance of having a committed proponent to elevate the salience of constitutionalism in political discourse. This can be seen by the increased attention that amendments have received in the election manifestos of political parties since 2017. However, the actual process of ratifying amendments will take considerable time: deliberation in the Committee on the Constitution, followed by debates and votes on each topic in each Diet chamber, followed by sustained public campaigning over 60 to 180 days, leading up to the fateful voter referendum. These will require the government to postpone other legislative priorities, and a “no” vote in the referendum will likely require the Cabinet to resign and call for new elections. Given the political risks, as well as competing demands on the government’s time today—the depreciation of the yen, the invasion of Ukraine, geopolitical risks in East Asia, the LDP’s ties to the Unification Church—it is not clear if Prime Minister Kishida or his immediate successors will have the appetite to push constitutional amendment forward in the near future.

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: The original copy of the Japanese Constitution stored in the National Archives of Japan. © Jiji.)

Bibliography

McElwain, Kenneth Mori. 2018. “Constitutional Revision in the 2017 Election.” In Japan Decides 2017: The Japanese General Election, edited by Robert J. Pekkanen, Steven R. Reed, Ethan Scheiner, and Daniel Smith, 297–312. Palgrave Macmillan.

McElwain, Kenneth Mori. 2020. “When candidates are more polarised than voters: constitutional revision in Japan.” European Political Science 19:528–539.

McElwain, Kenneth Mori, Shusei Eshima, and Christian G. Winkler. 2021. “The Proposer or the Proposal? An Experimental Analysis of Constitutional Beliefs.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 22 (1):15–39.

McElwain, Kenneth Mori and Christian Winkler. 2015. “What’s Unique About the Japanese Constitution? A Comparative and Historical Analysis” Journal of Japanese Studies 41.2: 249–280.

Winkler, Christian G. 2011. The Quest for Japan’s New Constitution: An Analysis of Visions and Constitutional Reform Proposals (1980–2009). Routledge.