Last Chance to Make Japan a Semiconductor Superpower Again?

Economy Technology- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Bringing Japan Back from the Brink

While the Kishida government started out by declaring that it would implement a new kind of capitalism, the government faces many geopolitical risks, including the sudden depreciation of the yen, inflation, North Korean missile launches, and the potential for military conflict in Taiwan. Japan is also a country that suffers from “first-world problems” in the form of budget deficits, the need to become carbon neutral, declining birth rates, and an ageing population.

If the government attempts to drive up the value of the yen through tighter monetary policy, it risks driving small businesses to the wall and smaller financial institutions to insolvency. Meanwhile, attempts to prop up living standards and industry performance will hurt the government’s finances, while efforts to implement DX, or “digital transformation”—the name given to a movement that aims to harness artificial intelligence, the internet of things, and big data to create new business models and reform corporate culture—and build more data centers will cause energy consumption to increase. Thus, the Japanese government is forced to consider multiple, mutually exclusive solutions to multiple challenges that interrelate in a complex manner. You could say that Japan is battered and bruised all over.

If we are to solve these challenges, we must first understand how they interrelate, and consider the priority, cost, and timing of the proposed solutions. We then need to rapidly and decisively select which initiatives to pursue and which to reject, all the while focusing on the “big picture,” having resigned ourselves to the fact that we need to accept a degree of sacrifice. The semiconductor industry will be a key part of this process.

Still Traumatized by Trade Friction

The yen is currently trading at its weakest level against the US dollar in 30 years. Three decades ago, Japanese semiconductor manufacturers enjoyed a 50% share of the market for memory semiconductors (dynamic random access memory, or DRAM), and completely eclipsed their rivals in terms of both market capitalization and patent applications. However, as is the case with the Japan-US relationship these days too, the United States felt threatened by Japan’s success, giving rise to friction between the countries. Faced with the rapid appreciation of the yen following the 1985 Plaza accord and the unfair US-Japan Semiconductor Agreement, Japanese manufacturers were rendered impotent as they found themselves forced to relocate production centers offshore, and invest in pure rather than applied research. Later, South Korea and Taiwan appeared on the scene with US backing, and the conquest pulled off by the Microsoft-Intel alliance, known as “Wintel,” precipitated a fall in Japan’s value-added exports, chiefly DRAM. Japan’s position as market leader was usurped by South Korea, Taiwan, and China.

Since 2000, Japanese semiconductor manufacturers have been unable to keep pace with the transition from vertical to horizontal integration that has taken place in the industry, and this has caused Japan’s share of the global market to fall below 10%. While Japanese manufacturers continues to rally in some areas, as exemplified by KIOXIA’s NAND flash memory, Sony’s image sensors, and Rohm’s power semiconductors, they do not excel at fabless manufacturing (an approach in which fabrication is outsourced to third parties by an operator that does not maintain its own plants, as contrasted with “foundries”—manufacturers that specialize in manufacture to order) of advanced logic chips, and produce almost none of the automation tools (semiconductor design support tools) required by fabless foundries.

The governments of the United States, South Korea, Taiwan, and China have all invested heavily in their semiconductor industries as a matter of national policy, also offering tax relief to businesses in the sector. In Japan, however, the trauma of the trade friction debacle has caused the government to be more subdued in its support for the industry.

If Japan’s semiconductor industry should disappear, it is domestic users that will be most affected.

The shortages that struck the semiconductor industry last year were not ordinary. Rather, scarcity of supply and price increases have now become the norm, causing the finished products like cars and robots, in which Japanese manufacturers have traditionally excelled, to become less competitive on the market. Semiconductors are core components that play a key role in the success of these high-tech products.

While the Japanese government has thus far focused on keeping its balance of payments positive, the energy and cloud-computing sectors could both post trillion-yen deficits by 2030, something that would further drive down the value of the yen. In such an eventuality, the semiconductor industry would also incur a trade deficit in the trillions of yen. While the difference in interest rates between Japan and the United States has contributed to the weakness of the yen, I believe the real cause is Japan’s declining industrial competitiveness, ageing society, and declining labor productivity, something that results from the nation’s slowness to embrace digital transformation.

Changing US Attitudes

To date, rather than building their own semiconductor factories, US manufacturers have concentrated on finance services, software design, platform design, and other design and planning-related services characterized by high added value, while depending on Taiwan and China for low-added-value manufacturing services.

However, Xi Jinping’s China has made significant inroads into both the software and platforms markets. China has also shown an interest in finance, with the digital yuan now threatening America’s scientific and technological dominance. Furthermore, the 5G mobile communications systems manufactured by Huawei, the world’s largest manufacturer of communications equipment, pose a threat to other countries’ national security.

In an effort to reduce its dependence on China, the United States is now looking to Japan to serve as a manufacturing hub for its high-tech industries. The current East-West conflict means that it has become too difficult for Western nations to keep using China as a production hub. Should a military conflict break out in Taiwan, whose manufacturers prop up the global smartphone, PC, and fabless semiconductor industries, the global supply chain would grind to a halt, eventually paralyzing the ability of Western nations to participate in wars.

While Japan’s share of the global electronic device market has fallen, Japanese manufacturers remain highly competitive in the manufacturing equipment and materials sectors. As the industry transitions from the “Moore” paradigm of increased miniaturization on planar silicon (a reference to Moore’s law—the observation by Intel cofounder Gordon Moore in 1965 that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit continuously doubles on a roughly regular schedule) to advances in fabrication technologies that are “more than Moore” (thanks to three-dimensional chipsets and other new technologies), this is the greatest opportunity yet for the Japanese semiconductor industry to stage a comeback.

It will also be the last such opportunity. Firstly, if the semiconductor industry is to stage a revival, talented engineers will be key, in particular the manufacturing engineers whose presence the United States is counting on. However, many of these engineers, who have overseen the building of multiple Japanese plants and know how they work, have already left to work in China, South Korea or Taiwan. They therefore need to be enticed back to Japan. However, this workforce is ageing, so time is of the essence. Secondly, there is not a second to lose in addressing the risk of military conflict in Taiwan. Thirdly, if manufacturers are to stage a comeback with a next-generation, “beyond 5G” mobile communication systems that will compete with Huawei, they must set their sights on the 2025 Osaka Expo. When you consider these facts, you can see that if a state-of-the-art logic hub is not established in Japan between 2025 and 2030, the United States’ expectations of Japan will wane, and we will miss our opportunity.

The METI Scenario

The Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry has begun formulating a roadmap for the revival of the semiconductor industry, including its June 2021 announcement of a new strategy for semiconductor and digital industries. Specifically, this core strategy comprises three steps: the establishment of manufacturing bases, the forming of alliances between Japan and the United States on next-generation technology, and the development of game-changing future technologies. As part of the first step, the government has encouraged the world’s largest semiconductor manufacturer, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, to set up a presence in Kumamoto, and has established a joint venture with Sony-Denso in the form of Japan Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing, whose new factory will go online in 2024.

Partnership between Japan and the United States will then see the design and establishment of next-generation semiconductors (featuring sub-2-nanometer process nodes and short turnaround times) in the latter half of the 2020s.

Finally, to make the mass production of next-generation semiconductors a reality, Japan is taking a two-pronged approach comprising the establishment of the LSTC, or Leading-Edge Semiconductor Technology Center, which is due to open later this year, and Rapidus, a new chip maker that was established in August.

The LSTC is an open platform research and development facility, which can be described as a Japanese version of America’s National Semiconductor Technical Center. In addition to securing the involvement of top Japanese researchers and technicians from the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Sciences and Technology, Riken, and the University of Tokyo, the LSTC is also affiliated with the NSTC, IBM research and development facilities in Albany, New York, and with Belgium’s International research institution, the Interuniversity Microelectronics Center.

Rapidus, which will fabricate the chips, has recruited Keidanren heavyweights as external directors, and counts major Japanese corporations among its shareholders, including Toyota and NTT, both of which will also be end-users of the chips. Receiving ¥70 billion from NEDO (the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization) and using a third of the ¥1.3 trillion budget allocated to the semiconductor industry in Japan’s second fiscal 2022 supplemental budget for technological development, the firm is establishing manufacturing hubs in conjunction with LSTC. Rapidus aims to ramp up production by 2027.

While the final step will not take place until at least 2030, under its IOWN (innovative optical and wireless network) concept, NTT aims to pull off a game changer with revolutionary photonic integrated circuit technology that harnesses both photons and electrons. Photonics is a power-efficient technology that harnesses both light and electricity to perform calculations. The technology’s significant energy-saving potential makes it the perfect vehicle to showcases Japan’s environmental contributions to the world.

These policies are significantly different from those adopted by previous government-led projects, in that rather than directly supporting industry, the government is both taking a user perspective and partnering with overseas manufacturers.

Long-Term Vision

If we harness communications networks and semiconductor-based digital infrastructure, we will be able to revitalize aging infrastructure and bring ailing corporations back to life. In addition, the platform strategy will create a body of success stories and case studies by region and corporation that enables the expertise gained to be standardized. By taking advantage of the weak yen, Japan will be able to export this success story as an example of country with “first-world problems” that has successfully implemented digital transformation. While the government’s books will suffer in the short term, in the long run, the initiative will have a positive effect. You could say that this is much like repairing a block of flats. There are issues that can be fixed now for a moderate repairs bill, but if this is put off for too long, the building as a whole will need to be rebuilt, at a far higher cost.

As I see it, Japan’s new brand of capitalism needs to be about security, peace of mind, stability, geopolitical security, and joint creation. Rather than leaving the market to its own devices, the government needs to take an interventionist approach, including from a national security perspective, based on agreement between the private and public sectors and on a long-term assessment of the overall balance of factors. As it did 50 years ago, Japan must again respond to America’s expectations by taking advantage of the weak yen and reinventing itself as an exporting nation, using the semiconductor industry as a model case.

The weak yen is today a source of pain, and Japan will be poor for the next few years. However, beyond that pain lies economic recovery. This is something that can be said not only of the semiconductor industry but also of Japanese manufacturing—in fact Japanese industry—as a whole. This is our biggest, and perhaps last, chance.

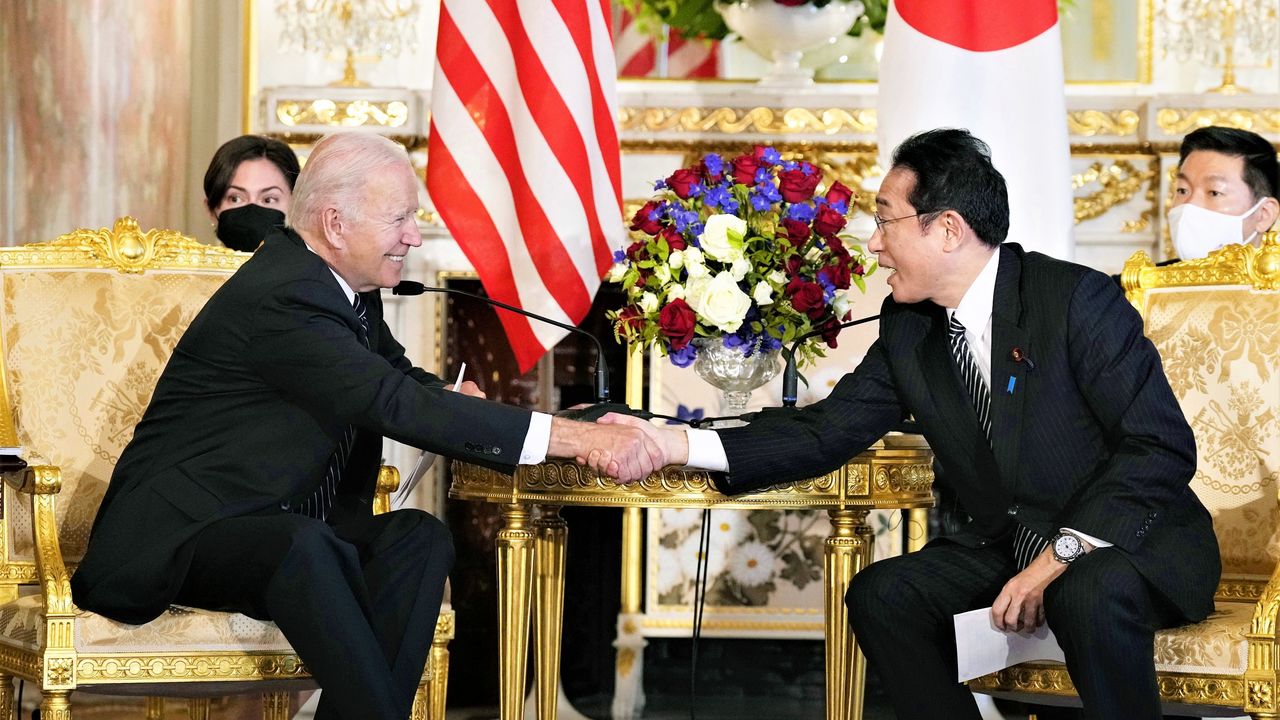

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, at right, and US President Joe Biden shake hands at the Japan-US leaders’ summit, having agreed to cooperate more closely on semiconductor research, development, and production and to give the United States access to semiconductors in the event of a military crisis, on May 23, 2022, at the Akasaka State Guest House, Tokyo. © Jiji.)