Time to Sever Political Ties with the Unification Church

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Why the Outrage?

Links between the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and the Unification Church (officially, the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification) have come under intense scrutiny since the assassination of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō on July 8, 2022. Yamagami Tetsuya, the man arrested for the crime, was a second-generation follower who accused the church of extorting millions of yen in donations from his mother, leading to the family’s financial ruin. He channeled his rage at the Unification Church against Abe, who he had reason to believe was closely connected with the group. The issue has turned into a huge political liability for the LDP and the government of Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, while raising broader issues about the status of religious organizations in Japan.

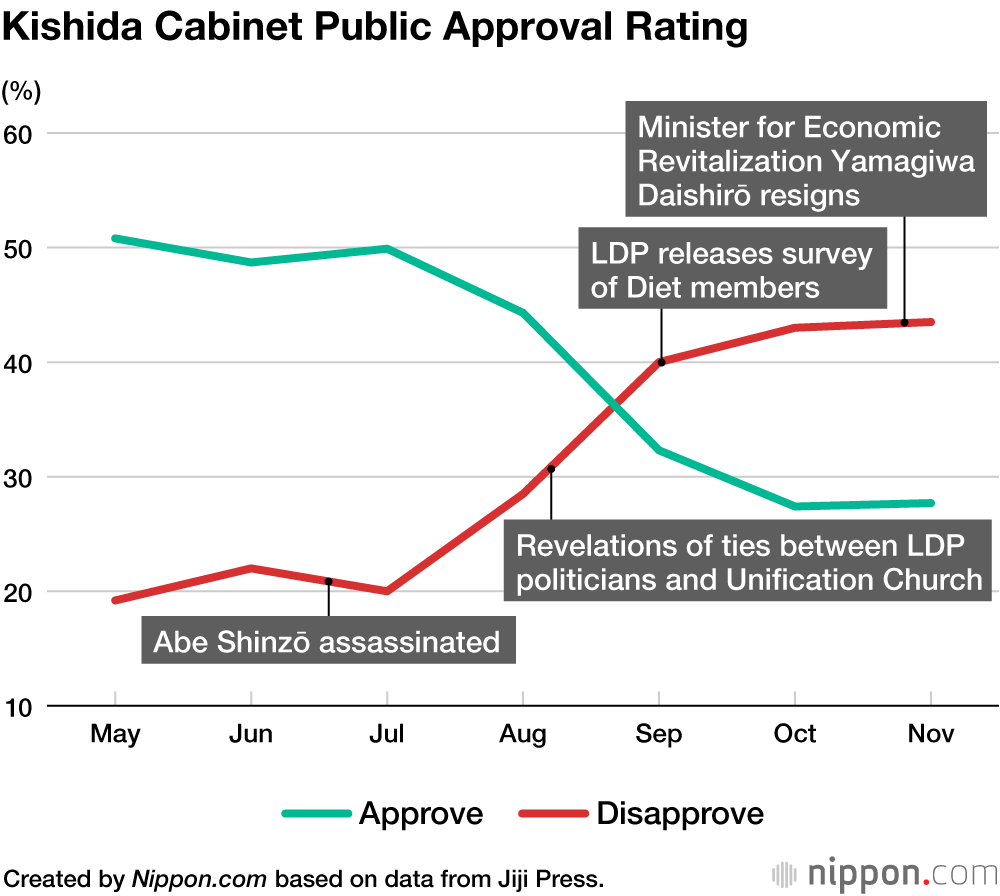

Reports of ties between LDP politicians and the Unification Church began to surface soon after Abe’s assassination, and the controversy was heating up even as Kishida announced his decision to hold a state funeral ceremony for Abe. The public backlash against that decision, along with widespread concern (surpassing 70% in most opinion polls) that the LDP was doing too little to address the Unification Church issue, contributed to a sharp drop in the Kishida cabinet‘s approval ratings.

Before proceeding further, we might ask why the public finds the relationship between the LDP and the Unification Church so distasteful. There are two basic reasons.

The first reason is the organization‘s association with predatory and fraudulent fundraising, extending back to the 1980s. According to numerous complaints and reports, members have been coerced and intimidated into making exorbitant donations to the church, in some cases reducing their families to poverty. Such revelations have fueled deep sympathy for second-generation victims of the church, extending even to Abe‘s alleged killer, Yamagami.

The second reason relates to the church‘s doctines, loosely based on the Christian tradition. The Unification Church, which blames Eve for humanity’s fall from grace, identifies Japan with Eve and Korea with Adam and concludes that it is just and proper for Japan to serve Korea. Such an anti-Japanese doctrine naturally sticks in the throats of many Japanese citizens.

Historically, the relationship between the LDP and the Unification Church can be traced to the Cold War anticommunist alliance between the church and the LDP’s right-wing factions. What this means is that the conservative wing of the LDP, which has fostered the rise of Japanese nationalism, willingly allied itself with a fundamentally anti-Japanese organization. Under the circumstances, it was natural for the public to demand accountability from the ruling party.

Sluggish and Inadequate Response

Neither the LDP nor the Kishida cabinet seemed to understand what a fraught issue this was. To the contrary, the prevalent assumption was that the uproar would blow over. Even now there is a strong tendency among LDP politicians to lump the Unification Church in together with other support groups. And since electoral cooperation with such groups—religious or not—is legal, they fail to see the seriousness of the problem. In short, a yawning gap has emerged between the party’s perception of the issue and that of the public at large.

Amid mounting accusations, the LDP responded by conducting a survey of its Diet members, the results of which it released on September 8, 2022. The survey itself was criticized as superficial and unreliable, and the party’s proposed response went no further than a revision to its recently adopted code of conduct. Moreover, the list of LDP Diet members with links to the Unification Church continued to grow even after the survey results were published. And while the LDP formally called on its local politicians to disclose and sever ties with the Church, it made no further effort to ascertain the extent of such ties ahead of the unified local elections scheduled for April 2023.

On October 17, Kishida tried to stanch the hemorrhage in public support by announcing a government investigation targeting the Unification Church and its fundraising tactics. Under the Religious Corporation Act, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology can submit questions to a religious organization suspected of abuses and, depending on the results of the investigation, request a court order for the group’s dissolution as a religious corporation. With this, the controversy ballooned from a matter of party governance—that is, whether the LDP would decisively break with the Unification Church—to a much broader issue, raising fundamental questions about Japanese society’s relationship not only with the Unification Church but with any religious group and its members.

But does this seemingly decisive response really address the core problem? Even if the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification is formally dissolved, the community of believers will remain. Moreover, unlike the two groups previously disbanded under the law (including the cult Aum Shinrikyō), the Unification Church has an extensive, worldwide network that will surely rush to the support of the Japanese community.

Wanted: Stiff Sanctions on Politicians

Strong measures are certainly needed, but they should be oriented first and foremost to promptly addressing the public’s deep suspicions regarding the LDP’s ties with the Unification Church. The first step is to conduct a thoroughgoing investigation of LDP politicians at the national and local levels. The second is to sever all political ties with the organization.

With regard to the first step, the investigation needs to be detailed and thorough, and its results must be released to the public and explained in full. It should not be limited to incumbent politicians; to the contrary, a major focus should be the relationship between the Unification Church and former Prime Minister Abe. The LDP and the government must put to rest the public’s suspicions that support from the Unification Church helped keep Abe in power for a record seven years and eight months.

As for the second step, political parties must commit to expelling any Diet or local assembly member hereafter found to have ties with the Unification Church. This step is unavoidable if our elected officials are to regain the public’s trust. The Unification Church has been actively involved in Japanese politics for decades, and it is sure to resume its courtship of politicians once the media spotlight has faded.

There is plenty of precedent for such a harsh penalty. In the wake of the Recruit scandal of 1988–89, even former Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro was obliged to relinquish his membership in the LDP. Japanese entertainers have been banished from show business when they were found to have close ties with “antisocial forces,” meaning crime syndicates. The Unification Church, with its history of coercive and fraudulent fundraising, must also be treated as an antisocial force. It is possible that some politicians were unaware of the kind of organization they were dealing with, but those that continue to maintain ties now that the truth has come to light should be forced to leave their party, or even public office.

Unfortunately, the LDP leadership seems convinced that the controversy will subside of its own accord. This attitude was vividly apparent from its decision to tap former Minister for Economic Revitalization Yamagiwa Daishirō to head the party’s COVID-19 task force just days after he was forced to resign his cabinet post over his obfuscation of close ties with the Unification Church.

Yamagiwa Daishirō responds to questions from the press after announcing his resignation as minister for economic revitalization. (© Jiji)

A Blow to Conservative Politics

The church’s alliance with LDP politicians goes back to the height of the Cold War era. Abe’s grandfather, Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke (in office 1957–60), felt a strong ideological bond with the virulently anticommunist Unification Church. The International Federation for Victory over Communism, a political arm of the church established in 1968, played a significant role in Cold War politics, helping spread anticommunist ideology and support for conservative policies. It was a key force behind such conservative movements as the campaign for an antispying law in the 1980s.

It was in 2015, during the Abe administration, that the government granted the organization’s request to change its official name to the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (even though a previous request was reportedly denied on the grounds that a name change could be used to obscure the church’s previous involvement in illegal or controversial activities). Media reports suggest that Abe also played a central role in efforts to boost the electoral prospects of weak LDP candidates by introducing them to church representatives. These and other circumstances threaten to fuel a bitter conflict between LDP members who want all ties with the church disclosed and severed and those who want to keep the relationship veiled in ambiguity.

Conservative media commentators allied with the LDP’s right wing have been conspicuously quiet in the wake of these revelations. Although normally eager to defend Abe and other conservative politicians, they can hardly condone the LDP’s ties with a church whose doctrines are so clearly antithetical to Japanese nationalism. By refusing to take a stand on the issue, they risk alienating the public.

The longer the LDP–Unification Church controversy continues, the more damage it will do to the conservative cause, ultimately eroding the LDP’s base. What is needed for the LDP and Japanese politics in the future is to rebuild a conservative ideology and a conservative camp that wins the trust of the people again.

The Challenge to Organized Religion

In addition to political repercussions, the controversy is confronting both new sects and traditional religious groups with the need to rethink the nature and scope of their activity in Japanese society. One important question is how to curb improper or dangerous proselytizing and fundraising while protecting freedom of religion. Another is whether it is appropriate for religious organizations to receive tax breaks and other special treatment.

In the event that the Unification Church is ordered dissolved, we will also confront the issue of how to handle the social inclusion of sect members, keeping in mind the hatred and ostracism faced by former followers of Aum Shinrikyō. It is hoped that the church will reconcile itself with Japanese society by refraining from political activities and devoting itself to its faith. This will lead to the spread of a spirit of religious tolerance between Japanese society and the church.

Religion is a highly sensitive matter, tied to each individual’s view of life and death. Other Japanese religious groups have issued statements on both sides of the issue, and the debate is unlikely to end anytime soon. As the social discourse continues, further questions are bound to emerge.

No End in Sight

Given these and other factors, the LDP is badly mistaken if it expects the storm to blow over anytime soon.

If the government does submit a request for a dissolution order, the solution of the problem will be left to the judicial system. Judging from past cases, it will take at least six months for the Supreme Court to issue a ruling. Meanwhile, assuming Yamagami is judged legally responsible for his actions, criminal proceedings—from the court of first instance to the Supreme Court—could drag on for years, and they will undoubtedly receive close media coverage.

Then there is the matter of the legislation enacted on December 10, 2022, to regulate the solicitation of donations by religious groups and aid the victims of abusive practices. The law was hurriedly drafted and passed under intense pressure from the opposition parties, and its wording of the key legal concepts is bound to prove problematic. It is unclear, for example, whether it will provide relief to second-generation members and others whose households were impoverished by the church’s demands. But the law will almost certainly open the door to a raft of lawsuits and other actions by sect members, former members, and relatives, and the campaign for stronger legislation will doubtless continue as well.

It will take years to sort out the issues raised by the Unification Church controversy, including the negative legacy of Cold War Japanese conservatism and the proper role of religion in Japanese life. But that process is already having a major impact on changes in Japanese politics and political sentiment in the twenty-first century.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Speaking under the pseudonym of Ogawa Sayuri, a former member of the Unification Church talks to reporters in Tokyo on October 7, 2022, about the trials of growing up as the child of two devout believers. © Jiji.)