New Promotion Criteria Needed to Keep Top Sumō Ranks Robust

Sports Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Ōzeki Are a Must for the Banzuke Ranking

At the November 2022 basho, ōzeki Shōdai failed to get more wins than losses and, in line with the kadoban rule applied to wrestlers of his rank, was demoted. Meanwhile, Mitakeumi, who had been demoted from ōzeki and had a losing record in both the July and September basho, could have been reinstated as ōzeki under a special rule had he won 10 matches at the November basho, but he also failed and thus did not return to the second-highest status.

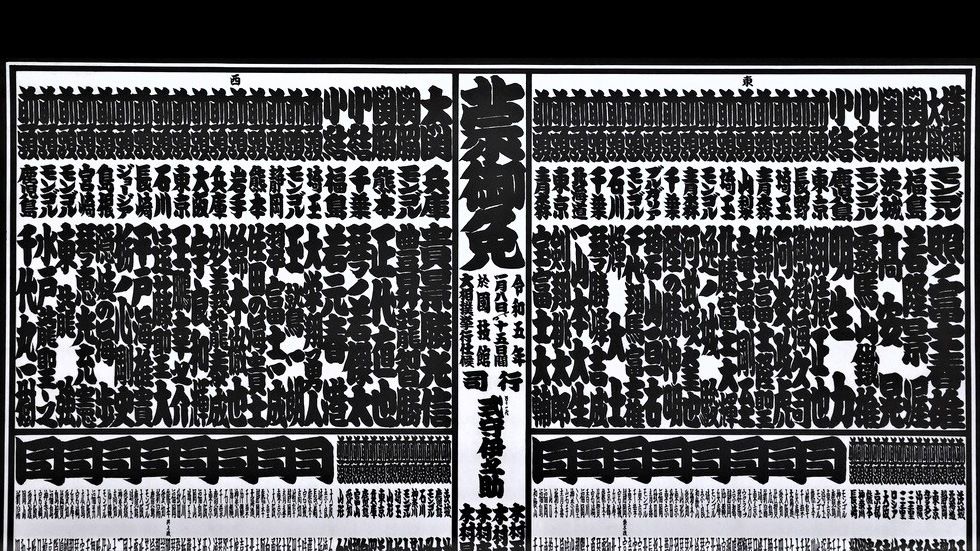

On the banzuke list of wrestlers for the January 2023 basho, Terunofuji is shown as yokozuna-ōzeki, covering both top slots on the east side, while Takakeishō is the west ōzeki.

Terunofuji remains a yokozuna, and the banzuke listing this time does not imply demotion. The yokozuna-ōzeki appellation was used because of an unwritten rule that while a banzuke can be published without the name of a yokozuna, listing ōzeki for both east and west is obligatory.

Although ōzeki today rank second after yokozuna in terms of status, this was not always so. Ōzeki were originally at the pinnacle of sumō, and exceptionally skilled rikishi who were deemed to have the requisite dignity were allowed to don the tsuna, braided rope, and allowed to enter the ring by themselves. This is said to have been the start of the yokozuna rank. It is not certain when this practice began, but the first such historically documented event was the accession to the rank by Tanikaze Kajinosuke, who was active between 1770 and 1790.

For the first time in 125 years, the banzuke for the January 2023 basho lists only one yokozuna and one ōzeki. It is also the first time since the January 1993 basho to have only two top-ranked rikishi, when the two ōzeki Konishiki and Akebono were on the list. At the time, promising wrestlers like Wakanohana, Takanohana, Musashimaru, and Takanonami were coming up the ranks; Takanohana, known as Takahanada at the time, was promoted to ōzeki soon afterward.

But even with the upper ranks so depleted nowadays, there are no rikishi who could soon be promoted to ōzeki if the current promotion criteria are followed.

Terunofuji underwent surgery on both knees after the September 2022 basho and is currently working on getting back into shape. Takakeishō, in addition to a chronic neck injury, suffers various other aches and pains, and it would not be surprising if one or the other of these men suddenly announced their retirement. Such a development would put the banzuke system at risk.

Terunofuji (center) performs the dohyō iri, ring-entering ceremony at Meiji Jingū on October 3, 2022. Two weeks later, he had arthroscopic surgery on both knees and sat out the November 2022 basho. (© Jiji)

If there came to be just one yokozuna and one ōzeki, would long-standing tradition be abandoned and a sekiwake allowed to rise to the ōzeki rank even without the requisite 10 wins in the previous tournament? Or would a banzuke with an empty ōzeki spot be created? These are possibilities that the Japan Sumō Association needs to discuss and prepare for.

Promotion Rules Tightened After the Futahaguro Affair

Unlike promotion to yokozuna, which requires two consecutive tournament wins in the rank of ōzeki, or an equivalent record, there are no clear-cut rules concerning advancing to ōzeki rank. Up until around the 1980s, it was informally agreed that ōzeki rank could be granted to a sekiwake or komusubi racking up 30 or more wins over three basho, but this yardstick was applied flexibly, on a case-by-case basis. The requirement for promotion was subsequently tightened to 33 wins or more over three basho as a sekiwake or komusubi after the 1990s.

This change most likely resulted after an incident involving then-yokozuna Futahaguro. This rikishi, who had reached the top rank without ever having won a tournament at the makuuchi division level, had a falling-out with Tatsunami, his stablemaster, and was forced to leave sumō four days later, at the end of 1989. Ever since, the criteria for promotion to yokozuna have become steadily more stringent.

The Shōwa period (1926–89) produced 18 yokozuna, but only three won promotion due to consecutive tournament wins. The others were all promoted on the basis of “or equivalent” performance, and among them seven—Asashio, Kashiwado, Tamanoumi, Wakanohana II, Mienoumi, Futahaguro, and Ōnokuni—had not won two consecutive tournaments immediately before promotion.

After 1990, the eight yokozuna from Asahifuji through to Harumafuji all won promotion after winning consecutive tournaments. More recently, Kakuryū, Kisenosato, and Terunofuji advanced to the top rank after achieving “or equivalent” records, including victories in one out of the two most recent tournaments, representing much better performances than the “or equivalent” of the pre-1989 years.

Given the tighter yokozuna promotion criteria now, many rikishi who could well have been promoted to the top rank prior to 1989 did not make the cut. These include Konishiki, who would have been the first foreign-born yokozuna, and Takanohana, who would have been the youngest to be promoted to the rank.

Wakanohana I Lived Up to His Promise

More stringent promotion requirements have also applied to ōzeki since 1989, the start of the Heisei period.

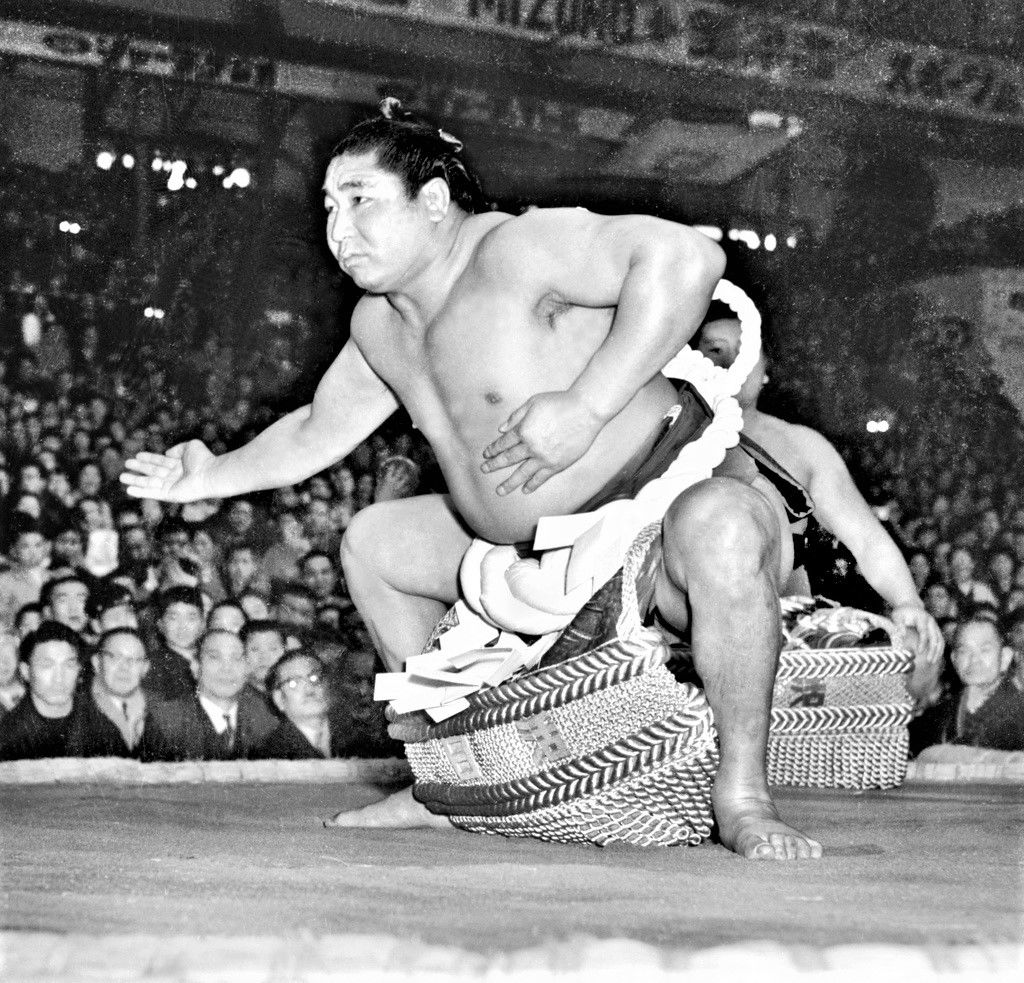

In the Shōwa years, 44 rikishi advanced to ōzeki rank, 14 of whom rose from sekiwake or komusubi after 31 or fewer wins over three tournaments. Until the 1960s, some were promoted with fewer than 30 wins over three tournaments, which would not happen today. Among them were Kagamisato, Wakanohana I, Kitabayama, and Kitanofuji with 28 wins, and Asashio with 29.

But notwithstanding such loose promotion criteria, four of these five later advanced to yokozuna. Conversely, even with 37 wins over three tournaments, men like Toyoyama, Hokuten’yū, and Tochinoshin, and Kotoōshū (36 wins), did not rise past the ōzeki rank.

Wakanohana I makes his first ring entrance as yokozuna at the spring 1958 basho. Despite being comparatively light, he was popular for his dynamic moves. Together with fellow yokozuna Tochinishiki, he ushered in the first postwar golden age of sumō. (© Kyōdō)

The informal requirement for promotion to ōzeki of past decades, 33 or more wins over three tournaments as sekiwake or komusubi, has today seemingly become the de facto standard. Since 1989 there have been 29 rikishi promoted to ōzeki, including Terunofuji, who rejoined the upper ranks after having fallen to a lower division, but none of them earned a promotion with fewer than a total of 31 wins over three tournaments. Except for Chiyotaikai, Kisenosato, Gōeidō, Asanoyama, and Shōdai, who were promoted after 32 wins, all the others racked up a record of 33 or more wins.

However, it seems to me that ōzeki prior to 1989, even though promoted under less stringent standards, were stronger than their counterparts of later decades.

The standard excuse given for today’s stricter promotion guidelines is ostensibly to create strong ōzeki. In the case of ōzeki, though, there is not necessarily any correlation between their performance at the time of promotion and their later records. In fact, a close look shows that by the time they were promoted to ōzeki, rikishi were often at peak performance or their abilities had already begun to wane.

Kaiō, today the oyakata (stable master) Asakayama, competed at the sekiwake rank in 12 consecutive tournaments starting with the January 1995 basho and was often in the final deciding matches. Musōyama, now the oyakata Fujishima, also notched 32 wins over three basho as sekiwake or komusubi starting with the January 1996 basho. Even so, both rikishi failed to be promoted to ōzeki. Although they ultimately reached that rank, had they been promoted while still at the peak of their vitality, as might have happened prior to 1989, it is quite possible that they could have made yokozuna.

Wins or Losses Not the Only Determinants

Seen in this light, there are major inconsistencies between the standards for ōzeki promotion after 1989 compared to the years prior.

When Kisenosato was promoted to ōzeki after the November 2011 basho with a record of 32 wins as sekiwake or komusubi, some sports journalists criticized the loose criteria by which he had been elevated. But head judge Fujishima, the aforementioned former yokozuna Musōyama, refuted their claims, saying “We are the experts here and we judged Kisenosato’s record based on his excellent overall performance. The decision to promote to ōzeki isn’t simply a matter of wins or losses. It’s the overall feeling that we get from a fighter’s record.”

Fujishima’s remarks were completely on the mark. Weighting a promotion to ōzeki depends not just on the number of wins. Much more important is judging rikishi performance in terms of technique and vigor.

Since yokozuna can never be demoted, retirement being the only option once their strength wanes at that level, promotion criteria are understandably strict. But if ōzeki, once demoted to sekiwake, can rise again to ōzeki rank, I feel that promotion criteria should revert to the looser pre-1989 requirements. This would also help revitalize the banzuke rankings.

Wakatakakage (28), at left, winner of the March 2022 basho, won 57 matches in the previous year’s six grand tournaments. Hopes are high that he will win promotion to ōzeki in 2023. (© Jiji)

Sekiwake Hōshōryū (23), at right, earned the Technique Prize at the November 2022 basho with a repertoire of moves including the kawazugake leg entanglement throw. With spectacular lower body strength like that of his uncle, the former yokozuna Asashōryū, he is also a prime contender for promotion to ōzeki. (© Jiji)

Ōzeki Wins No Longer a Sure Thing

Rikishi do not suddenly advance to the rank of yokozuna simply by winning the previous tournament. The banzuke system does take previous performance into account, but the way in which rankings are assigned is an opaque process with a solid sprinkling of Japanese vagueness.

In the Edo period (1603–1868), especially, it was sometimes the case that exceptionally large men, even without any prior sumō experience, were ranked as ōzeki simply to attract spectators. These men, whose only role was to enter the dohyō by themselves, were known as kanban (customer-drawing) ōzeki, and it is clear that their entertainment value was a primary reason for their presence.

But with the advent of the Meiji period (1868–1912) and the arrival of Western sports, the idea of ranking according to performance gradually took hold.

In professional baseball, players like Suzuki Ichirō, winner of the leading hitter title for seven years running (eight years, if his time in the US Major Leagues is counted) was a superb batter. But as a matter of fact, even after winning the hitter title, many more players end up with a subpar batting average in the .200 range the following season.

In sumō too, a creditable record over just three basho does not guarantee repeat performances of the same caliber. If the banzuke ranked only rikishi with a consistently brilliant record like that of Ichirō, the system would collapse. Winning and losing are part and parcel of sports, and a system that expects yokozuna and ōzeki to perform perfectly at every tournament is not consistent with the idea of what sport is.

The sumō world today is having difficulty attracting talented youths and is permanently short of recruits. Meanwhile, everyone has access to social media, making today’s rikishi much more accessible to fans than ever before, producing changes in the temperament of the average wrestler. This said, currently active wrestlers seem much more focused on sumō than their predecessors. In other words, notching a winning record in a tournament just by virtue of being an ōzeki is no longer so easy.

As an entertainment Japan can be proud of, sumō is a blend of sports and culture, but achieving the right balance is difficult. Reviewing the ōzeki system, and by extension, the yokozuna system, is something that should be done so as to pass our national sport on to the next generation.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 28, 2022. Banner photo: The most recent banzuke lists only one yokozuna and one ōzeki, for the first time in 125 years. At far right, east Yokozuna Terunofuji is shown as yokozuna-ōzeki; just left of center Takakeishō appears as west ōzeki. © Kyōdō.)