Demystifying US Electoral Politics: A 2023 Primer for America Watchers

World- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Predictable Surprise

The 118th US Congress is now in session. In the 2022 midterm elections held last November, the Democratic Party lost control of the House of Representatives, while holding onto a slim majority in the Senate. Yet Democrats were celebrating. US political observers have come to expect a midterm electoral backlash against the president’s party, and given President Joe Biden’s low approval ratings, there had been much talk of a “red wave” that would hand control of both houses of Congress to the Republican Party. The wave never materialized.

In fact, not everyone was surprised by the results. Internally, the Democratic Party was aiming to keep its majority and gain two seats in the Senate while limiting the Republicans’ margin in the House to single digits, which is more or less what happened. A minority of media pundits also got it right. Simon Rosenberg, a Democratic strategist and political commentator, merited special mention by the New York Times for consistently maintaining that there would be no red wave, as the Democrats and Republicans were much more evenly matched than many of the polls indicated.

Leaving aside public sentiment, the Democrats enjoyed several fundamental advantages going into the 2022 midterms. In the Senate, 20 of the seats up for election were held by Republicans, while just 14 were held by Democrats. Five Republican senators were retiring, as compared with one Democrat, and three of the retiring senators were from swing states like Pennsylvania—where, in fact, the Democrats were victorious. In the House of Representatives, redistricting (in accordance with the results of the latest US Census) had increased the number of Democratic and Democratic-leaning seats, according to an analysis released by FiveThirtyEight.

But these technicalities only go so far in explaining the outcome of the 2022 midterm election. Other key factors deserve a careful look, as they highlight the unique dynamics of electoral politics in the United States. In the following, I examine those factors and their implications.

The Culture Wars and Abortion Rights

One aspect of American politics that mystifies the Japanese people is the sharp conflict over religious and social values—the so-called culture wars. The pivotal role that abortion rights played in the midterm elections is a prime example.

One of the standard ways in which the minority party rallies support in midterm elections is by fanning voters’ victim mentality, claiming that the government is depriving them (or intends to deprive them) of what is rightfully theirs. In the 2010 midterm election, held under the administration of President Barack Obama, Republicans energized the base by playing on fears that Obamacare would deny Americans the right to choose the kind of healthcare they receive. In 2022, the Democratic Party focused on the threat to a woman’s right to terminate her own pregnancy.

Setting the scene was the US Supreme Court’s June 24, 2022, decision overturning Roe v. Wade, which established a woman’s right to an abortion. In the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, abortion rights emerged as a symbol of the alleged Republican-led attack on civil liberties. Transcending women’s issues, it helped to energize several different voting blocs, including independents and the LGBTQ communities, as well as registered Democrats of both genders.

State legislatures emerged as the new battleground in the abortion fight. In all five states where the issue was on the November 2022 ballot, voters rejected new restrictions or supported new protections for abortion rights. Moreover, those ballot measures boosted turnout in a way that benefited the Democratic candidates for governor and state legislature. In fact, this was the first US midterm election since 1934 in which the president’s party successfully defended all of its state-level legislative majorities.

For those observing the elections from Japan and other countries, it must have seemed strange that Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization would trump inflation and President Joe Biden’s low approval ratings. Abortion is not a politically divisive issue in Japan. Despite the presence of a substantial Christian community, the Japanese people have almost no experience with the kind of fundamentalists who oppose the teaching of evolution in school. In the light of their understanding of the separation of religion from government and political power (Article 20 of the Constitution), they find it hard to comprehend the level of involvement of Christian sects and churches in US politics.

But the “separation of church and state” in the United States has always been about preventing political authorities from forcing a particular religion on the people, and its application is loose by Japanese standards (notwithstanding the political activities of the Unification Church, which have stirred such controversy of late). Although media attention has tended to focus on the Christian right and its influence on the GOP, the Democratic Party also relies on electoral support from faith-based communities, including liberal Catholics and Black churches. Religious figures have been at the forefront of the movements for progressive political reform and civil rights.

To a large degree, religion informs the deep political divide over such social issues as feminism and LGBTQ rights—another way in which the United States differs from Japan. In Japan as elsewhere, campaigns for equal rights and opportunity regardless of gender or sexual preference have gained momentum, but the basic context is Japan’s patriarchal, male-dominated society, not intolerance rooted in religious belief. This country has seen nothing comparable to the massive religious backlash that has made issues like same-sex marriage and abortion so politically volatile in the United States.

Former President Donald Trump (unlike former President George W. Bush, another Republican) is neither an evangelical Christian nor particularly devout. Nonetheless, he secured the electoral support of evangelicals and other members of the Christian right with his promise to appoint conservatives to federal judicial positions, including the Supreme Court, and he delivered on his promise. These appointments have had implications for a number of quintessentially American issues, including gun rights, race, and immigration. But the Supreme Court’s ruling overturning Roe v. Wade has probably been the most consequential from a political standpoint. The rejoicing with which social conservatives greeted the decision and the electoral backlash the ruling triggered underscore the critical role of the culture wars in US electoral politics.

Candidate Selection in the United States and Japan

Another major factor sometimes overlooked by those unfamiliar with the US electoral system is the role of party primaries, which have a fundamentally different dynamic from general elections.

Japan has no primary elections, a circumstance reflecting the centralized power structure of our political parties. In Japan, it is the parties themselves—most particularly the top national officers—that select the candidates for each single-seat district and proportional-representation block; voters first learn the names of the candidates from the standardized posters displayed in specified places after the official start of a very short campaign season. In Japan’s House of Representatives elections, each voter casts two ballots: one for a candidate in the local single-seat constituency, and one for a party, in order to assign regional-block seats allocated by proportional representation. In practice, party affiliation usually determines both votes. A candidate who loses in the single-seat constituency may still secure a block seat via proportional representation if he or she is high enough on the party’s list.

In the United States, by contrast, local party affairs are managed by highly autonomous local chapters, and each party’s candidate for Congress is selected by local voters in a primary election. The 2009 HBO documentary By the People: The Election of Barack Obama highlights the role of the primaries in presidential elections, paying special attention to the Iowa caucuses, where Obama gained critical momentum by winning the first event on the 2008 presidential election calendar. The film shows how grassroots involvement by passionate young voters and volunteers helped transform the Democratic Party from the ground up. Although foreign coverage of US presidential elections tends to focus heavily on the general election—when the race is down to two competitors—the contribution of America’s unique brand of grassroots politics is most evident in the primaries, which establish the intraparty power structures that will shape the presidency and Congress in the coming years.

To appreciate the difference between American and Japanese election campaigns, it is instructive to compare By the People with the 2020 Japanese documentary Naze kimi wa sōri daijin ni narenai no ka (Why You Can’t Be Prime Minister). This film offers a frank portrayal of one politician, Ogawa Jun’ya, and his experience with the top-down electoral decisions and machinations of Japan’s fractured opposition parties. Originally elected to the House of Representatives from Kagawa Prefecture as a member of the center-left Democratic Party of Japan, Ogawa was eventually forced to run for reelection as a candidate of the up-and-coming, right-leaning Kibō no Tō (Party of Hope) when the leadership of his own party embarked on a controversial merger and dissolved its own House of Representatives caucus. Unable to explain his shift to former supporters in Kagawa, Ogawa lost the race in his local district.

Since 1993, Japanese opposition parties have been forming, merging, and disbanding in a dizzying series of moves dictated by a centralized leadership. The selection of candidates for Diet seats is also controlled by the top officials at the national level, leaving virtually no room for voter involvement in the internal decision-making process. Someone you voted for as a member of one party can suddenly turn around and ask for your support as the candidate of a completely different organization with different policies. If it is a single-seat constituency, like the elections in the United States, votes can result in support for candidates, not just for parties, especially in the primary. In that case, changing party affiliation for ideological and strategical reasons must be considered as a decision by the politicians whom voters elect. However, in Japan, even a politician who was only able to secure or retain a Diet seat thanks to proportional representation is free to leave the party he or she was supposed to represent. The voters have no say in the matter. Unlike Japan, in other East Asian democracies like Taiwan, if an at-large legislator loses his or her party membership, this comes with a loss of the legislative seat, and the next person on the list becomes the legislator.

The Dynamics of US Primaries

In the United States, state-level primary elections are the means by which the parties choose their candidates for Congress and the presidency, and the dynamics of these races are nothing like those of general elections. Especially today, in the era of political polarization and hyper-partisanism, the formula for securing the support of the party base is entirely different from that needed to win over swing voters and independents in a general election. In other words, there is a growing disconnect between the kind of candidate who can win a primary and the kind who can win a general election, creating a major headache for party strategists.

The 2022 midterm elections underscored this disconnect. “Election deniers” and hard-right candidates endorsed by Trump did extremely well in the Republican primaries. Wyoming voters resoundingly rejected incumbent Representative Liz Cheney, a conservative icon who harshly criticized Trump in the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election. In the general election, however, Trump-endorsed challengers fared poorly overall—one important reason the “red wave” failed to materialize. This can be taken as a sign that the majority of American voters, including independents, have rejected Trump‘s brand of politics. But it does not mean the GOP itself has rejected Trump or Trumpism.

In the wake of November’s disappointing results, some Republican politicians have begun distancing themselves from Trump, sensing a shift in the prevailing winds. But the Republican “establishment” can scarcely rest easy. The populist surge that fueled Trump’s rise is alive and well. When a handful of members of the Freedom Caucus held up Kevin McCarthy’s election as speaker of the House at the beginning of the year, they were acting not out of personal loyalty to Trump (who in fact asked them to support McCarthy) but to the cause of grassroots populism and an ethic that glorifies rebellion against an entrenched leadership.

The five-day deadlock over the election of a speaker of the house was viewed by many in Japan and elsewhere as a sign of American democracy’s dysfunctionality. But one could argue that the process gave voice to the diversity of opinion within the GOP without actually impeding the core functions of government. Democracy comes in many flavors, and opinions will always differ as to the proper role of government and the importance of efficiency versus democratic decision making.

We must also bear in mind systemic differences in party discipline and governance when observing such developments. American political parties have neither central headquarters nor top executive officers in the sense that their Japanese counterparts do. Holding such parties together is a challenge, especially in this age of political polarization and fragmentation. The key to unity is a shared antagonism toward a powerful archenemy.

Internal Conflict in Both Parties

The third factor to keep in mind about US electoral politics is the internal divisions within both of the major parties. For observers outside the United States, it can be difficult to see beneath the surface to these deepening internal conflicts and grasp their changing character. In the context of a two-party system that has proven extremely hostile to the formation of politically effective third parties, internal policy conflicts (though seemingly minor compared to the difference between the two parties) have the potential to play a major role in national politics.

Until fairly recently, the Democratic Party was split between a liberal and a moderate wing, but a new generation of unabashed leftists has emerged as a dynamic force in Congress. These are progressives with roots in such activist movements as Black Lives Matter and the election campaigns of Senator Bernie Sanders. Their feelings of loyalty to and identity with the Democratic Party are not especially strong, but they recognize the impracticality of launching a third party, and they believe they can change the Democratic Party from within.

Just two weeks before the midterm elections, members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus sent an open letter to President Biden urging the administration to take a more active diplomatic role in the war in Ukraine with the goal of negotiating a ceasefire as soon as possible. Although the letter was quickly retracted, it contradicted the widespread perception that Democrats in Congress were unanimous in their support for Biden’s policy of providing military assistance to Ukraine. It was particularly alarming for the party to see these latent divisions erupting in the midst of the midterm election campaign.

Ironically, Donald Trump is both the glue that holds this Democratic coalition together and the catalyst that drives voter turnout. The Democrats’ relatively strong showing in the midterm elections can be attributed to Trump, including his role in the Supreme Court ruling that turned abortion into a major election issue. Ironically, each new effort by Trump to assert his ongoing political relevance—as by his November 15 announcement that he intends to run for president again in 2024—serves as a further deterrent to feuding within the Democratic Party.

As speaker of the House for many years, Nancy Pelosi filled a similar function for the Republican Party, but she has ceded leadership and can no longer function as a target. President Biden does not inspire the same level of unifying rancor. Without a bête noire like Pelosi, or like Hillary Clinton during the 2016 presidential election, the sparks of disunity will continue to smolder in the Republican Party. Yet any further intensification of anti-Democrat feeling could render Congress dysfunctional, potentially damaging the GOP’s 2024 prospects. Given the Republicans’ slim majority in the House of Representatives and the stubbornly rebellious elements within the party, Speaker McCarthy will have his work cut out over the next two years.

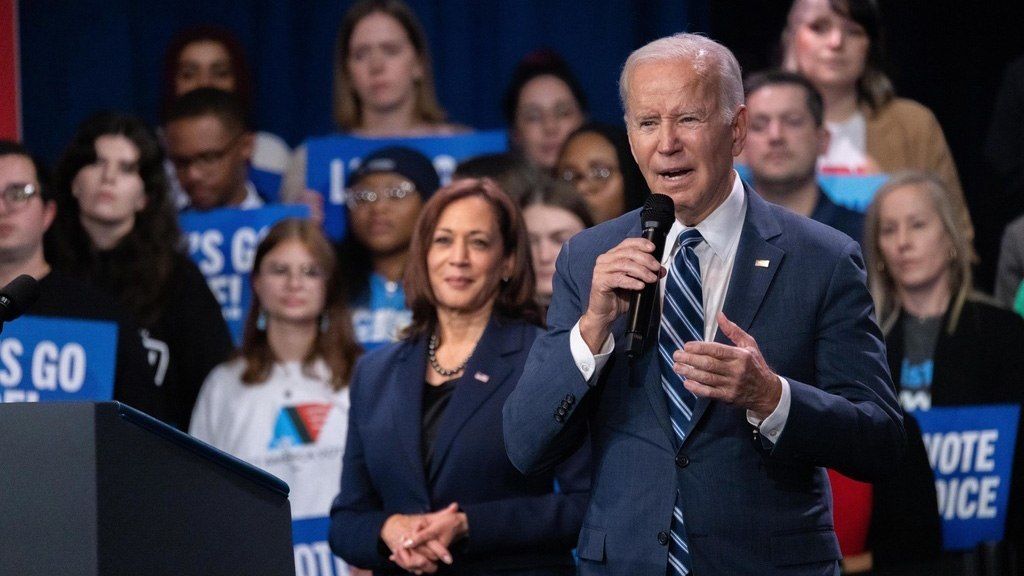

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: US President Joe Biden speaks at a rally of the Democratic National Committee in Washington, DC, on November 10, 2022, following the midterm elections. © Getty Images/Kyodo.)