Modernizing the US-Japan Alliance: Counterattack Capabilities and Layered Security Cooperation

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

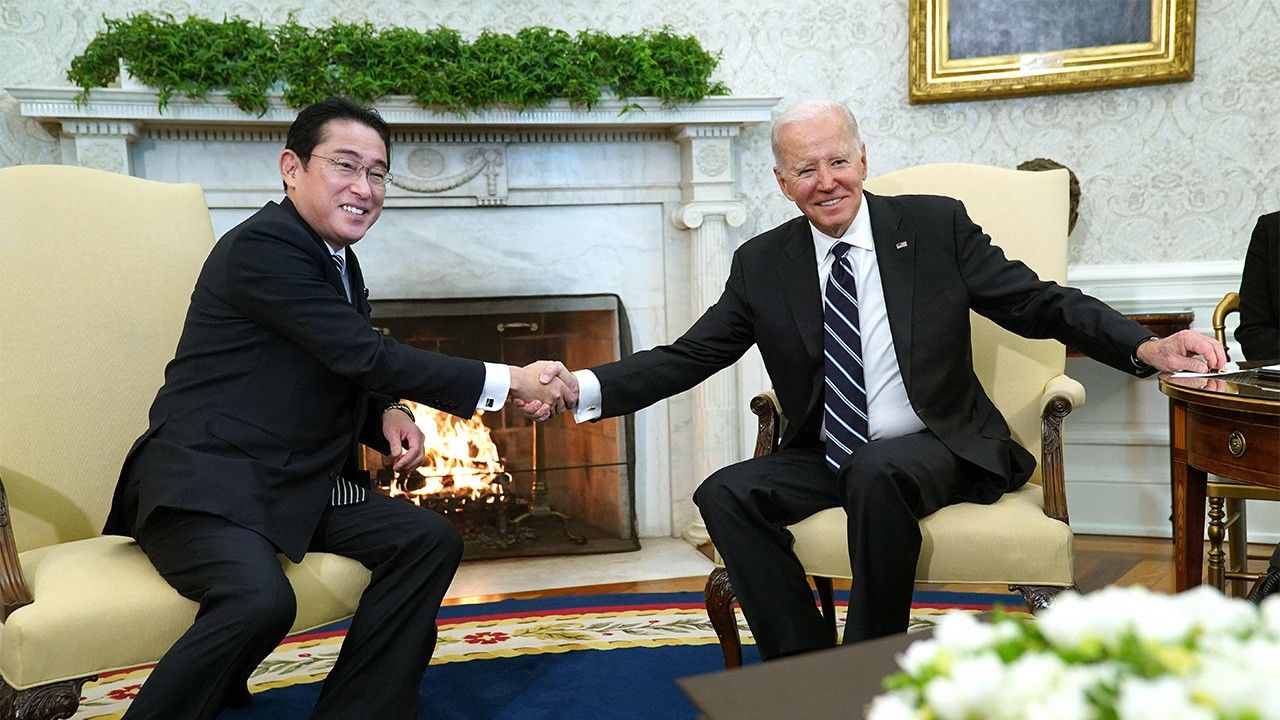

In December 2022, the cabinet of Prime Minister Kishida Fumio approved revisions to three key Japanese security documents and announced that the Self-Defense Forces would acquire a “counterattack capability.” Less than a month later, Kishida visited Washington DC to meet with President Joe Biden. The Joint Statement following the meeting noted that “President Biden commended Japan’s bold leadership in fundamentally reinforcing its defense capabilities.” It also indicated a mutual commitment to “modernize the US-Japan relationship for the twenty-first century.”

This is remarkable language that portends a potentially much stronger alliance and represents an excellent beginning to Prime Minister Kishida’s 2023 diplomatic program. However, many long-standing military coordination issues between the United States and Japan will need to be fleshed out in order to realize these ambitions. Challenges include enhancing layered security cooperation with countries other than the United States and operationalizing Japan’s counterattack capabilities.

The Looming “2027 China Risk”

A key reason why the Kishida administration was so eager to strengthen the alliance following revision to Japan’s security documentation is the increasing concern about the “2027 China risk.” This is the idea that China will be most likely to launch an invasion of Taiwan around that year, when Beijing will mark the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army. This timeframe also overlaps with the expiration of Xi Jinping’s already unprecedented third term as China’s supreme leader. The unification of Taiwan would virtually guarantee Xi a fourth term, should he covet it.

In 2022, Prime Minister Kishida reacted strongly to Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine. Condemning Moscow’s unilateral seizure of territory, Kishida followed up at the 2022 G7 Summit, held in June in Germany, by announcing strong sanctions on Russia and strong support for Ukraine. Asserting that “Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow,” the prime minister sought to connect instability in Europe to the situation in East Asia and especially to China’s hegemonic actions surrounding the Senkaku Islands and Taiwan. When President Biden visited Japan in May last year, Prime Minister Kishida repeated his previous commitment to “fundamentally reinforce Japan’s defense capabilities” while also promising that he would secure a “substantial increase” in the Japanese defense budget to realize this goal.

On December 16, the Kishida cabinet then approved the three documents mentioned above: Japan’s new National Security Strategy, its first ever National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Build-Up Program for the years 2023–27. The government also announced it would increase security-related spending to 2% of GDP by 2027. With the “2027 China Risk” in mind, the government also announced that it would fill the void in its stand-off missile capabilities by accelerating the procurement of American-made Tomahawk cruise missiles.

The Significance of “Modernizing the Alliance”

The use of the word “modernize” in the recent joint statement following the most recent Biden-Kishida summit—rather than the traditional “strengthen”—is significant. Within the US-Japan alliance framework Japan has traditionally fulfilled the role of “shield” in that it would exclusively focusing on defending itself. It would, however, leave power projection into foreign territories up to the United States as the alliance’s “spear.” With the announcement that Tokyo will develop its own counterattack capabilities that can hit enemy military bases, Japan will now increasingly take hold of the “spear” itself. With China building up its military at a rapid pace and North Korea increasing both its missile testing and nuclear-weapons-related activities, both Tokyo and Washington recognize the need to adapt and “modernize” the division of roles within the alliance so that Japan is not solely reliant on the United States for offensive power.

Tokyo’s decision to acquire even a limited counterattack capability could be a watershed moment for Japan’s postwar security policy. At a recent speech at John Hopkins University, Prime Minister Kishida himself shared his belief that “this decision represents one of the most historically critical milestones for strengthening the alliance, following such precedents as the conclusion of the Japan-US Security Treaty by Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru, the revision of the Treaty by Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, and the Legislation for Peace and Security by Prime Minister Abe Shinzō.” The Biden administration strongly welcomed this shift in Japan’s security policy as it represents Tokyo becoming increasingly aligned with the United States’s own concept of “integrated deterrence.” Outlined in the US National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy documents last October, this concept emphasizes the integration of all domains of warfare to enhance deterrence and envisages an even greater role for allies and partners to support American efforts.

Layered Security Cooperation

Prime Minister Kishida’s 2023 diplomatic efforts were greatly assisted by a tailwind in the form of Japan beginning a two-year term as a nonpermanent member of the United Nations Security Council while also assuming the presidency of the body in January. As Japan will also chair the G7 and host the G7 summit in May in Kishida’s hometown of Hiroshima, the prime minister’s visits to Canada, France, Italy, and Britain even before setting foot in the United States constituted an excellent use of Japan’s agenda setting responsibilities.

In France, Kishida and French President Emmanuel Macron vowed to build on their “special partnership” by continuing security cooperation and joint military training and agreed to hold a “2-plus-2” meeting between the foreign and defense ministers of the two countries in the first half of 2023. In Italy, the prime minister agreed to upgrade the Italy-Japan relationship to a “strategic partnership” and also coordinate “2-plus-2” talks. This agreement builds on the three-nation (Japan-UK-Italy) development project to build a next-generation fighter. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Prime Minister Kishida then signed the Japan-UK Reciprocal Access Agreement to facilitate joint training and military visits on January 11.

Greatly strengthened during the tenure of the late Prime Minister Abe, the UK-Japan relationship is particularly notable. The two countries have essentially developed into “quasi-allies,” and in September 2021 the British Royal Navy’s most advanced aircraft carrier visited Yokosuka to conduct joint exercises with Japan’s navy with an eye on China. The RAA with the United Kingdom is only Japan’s second after Australia—another quasi-ally.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was not only a perceived as a direct threat in Europe but also raised the alarming prospect that China and Russia could act in concert to undermine the international order. As the only G7 member from Asia, Japan making its allusion to Ukraine being a preview of what is to come in Asia carried significant weight. The US-Japan alliance will continue to serve as the central axis for deterring military adventurism by Beijing, but it is also extremely important for Tokyo to pursue layered security cooperation by deepening partnership networks with like-minded countries and quasi-allies that share similar values. Therefore, Japan’s coordination with countries in Europe and with Canada and Australia is important.

The Race Against Time

The Kishida administration’s plans to develop Japan’s counterattack capabilities and increase security-related spending to 2% of GDP represent a major shift in security policy that could scarcely have been imagined five years ago. However, nothing has yet been accomplished. As the new defense budget will be debated in parliament during the current Diet session, the prime minister must continue to work on gaining public acceptance.

Since domestically developed missiles will not be ready by 2027, the Japanese government made the decision to purchase Tomahawk cruise missiles to fill the void in Japan’s stand-off capabilities. However, even if the United States green lights the purchase, Tokyo will still need to determine where, when, and how the missiles will be deployed. To enhance deterrence, Tokyo will also need to accelerate plans to equip multiple launch platforms with stand-off missiles, including Aegis-equipped destroyers, submarines, and fighter aircraft. This could take time, and Tokyo will also need to integrate the US military’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance functions with those of the SDF for target identification, selection, and guidance to ensure the potency of Japan’s counterattack capabilities.

Furthermore, Japan must coordinate with the United States to defend Japan’s outer islands (including the Senkaku Islands) and also with Taiwanese authorities to safely evacuate Japanese nationals during a Taiwan contingency. It is a race against time to head off the “2027 China risk” surrounding Taiwan. Tokyo needs to promptly and efficiently initiate and accelerate working level preparation to ensure Japan is ready by 2027.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, at left, and US President Joe Biden shake hands during a US-Japan leadership summit at the White House on January 17, 2023. © AFP/Jiji.)