Sustained Wage Increases the Key to Monetary Normalization: An Interview with Ex-BOJ Executive Director Momma Kazuo

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Wage Increases at a 30-Year High

INTERVIEWER The war in Ukraine has caused crude oil, grain, and other prices to surge upward since 2022, greatly impacting a Japanese economy just as it was recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic. What is your assessment of this year’s spring wage offensive as a response to rising prices?

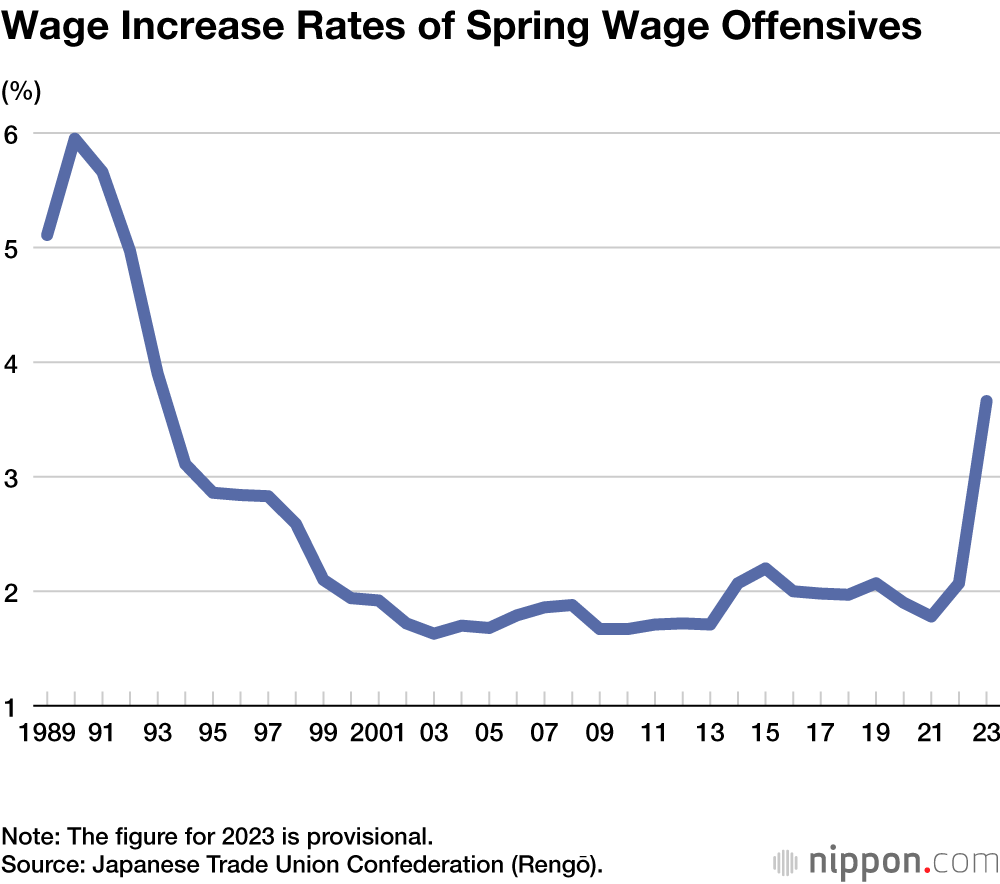

MOMMA KAZUO This year’s shuntō, or spring wage offensive, resulted in a provisional wage increase rate of 3.7 percent. Such an increase has not been seen in thirty years. Since prices had risen by a considerable amount, companies likely felt that they needed to respond in some way. Moreover, Japan’s economy is recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, and inbound tourism has nearly returned to its former level. Some of the wage increases likely reflect labor shortages in such service sectors as accommodations and eating and drinking services.

The question is, will these wage increases continue in 2024 and beyond? It’s still too early to pinpoint whether wages will continue to rise at this year’s rate of 3.7 percent, or say 4 percent, or at a rate that the BOJ finds desirable.

INTERVIEWER Will it be difficult for wages to continue rising at this year’s rate?

MOMMA It’s becoming more likely that wage increases will continue to some degree, but there is still much uncertainty. First, there is the risk of a recession in the United States. It is quite possible that growth will not just slow but clearly turn negative. The interest rate hikes of the Federal Reserve have yet to take full effect. Inflation is not tamed easily without the economy experiencing negative growth.

This year’s shuntō wage increases resulted from temporary factors, like sudden labor shortages in the service sector. Another important factor was the growing awareness of companies that they needed to respond to some degree to the upsurge of prices. The spring wage offensives of 2024 and beyond will be affected by whether expectations for medium- to long-term growth can be sustained. There is, however, no such clear outlook at the present moment. The BOJ is currently maintaining a cautious stance and shows no sign of changing its monetary policy.

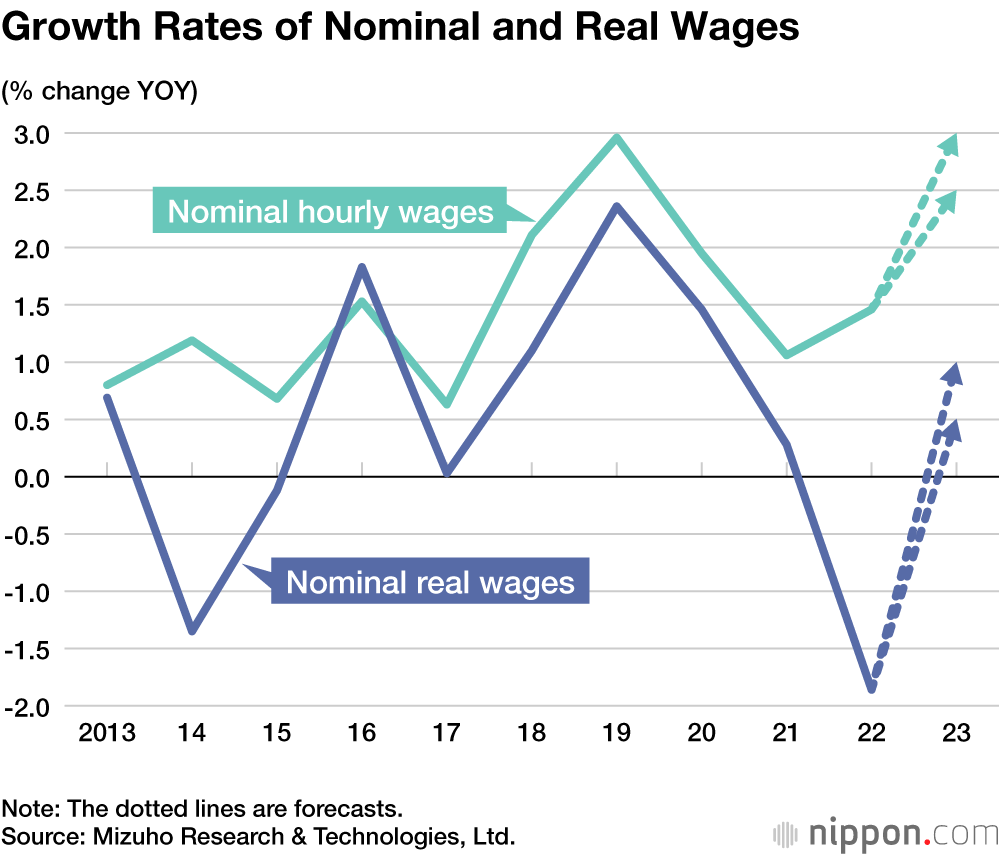

INTERVIEWER The growth of real wages, adjusted for inflation, remains negative year on year. What is the outlook for real wages?

MOMMA There is a strong possibility that real wages will increase year on year in the second half of 2023. With nominal wages likely to rise 2.5 percent to 3 percent, should the increase of consumer prices (excluding fresh foods and energy) slow from 4 percent to around 2 percent, it is possible that real wages will grow by 0.5 percent or 1 percent. Whether such an increase can be sustained will depend on next year’s spring wage offensive.

Will Wage Increases Continue?

INTERVIEWER Is the BOJ paying attention to next year’s spring wage offensive?

MOMMA Very much so. You could say this is the greatest interest of the bank.

INTERVIEWER Once the spring wage offensive of 2024 is over, how far would the BOJ like wages to rise to begin normalizing in some manner its monetary easing of a different dimension?

MOMMA Policy decisions are not made mechanically based on wage figures. The BOJ is intensely monitoring whether peoples’ sentiment toward or views about inflation are changing. That prices or wages do not rise has become a part of conventional thinking, or public sentiment. Unless such sentiment changes, a stable and sustainable inflation target of 2 percent will not be achieved.

To explain why the BOJ is so interested in the spring wage offensive of 2024, if wages increase by 3 percent to 4 percent two years in a row, this will be a sign that people are beginning to act based on the sentiment that wages and prices rising by about 2 percent is normal. Wages are not so much a force that elevates prices, but are more like a thermometer. It’s not necessarily correct to view wages as the cause of events. Should public sentiment change, wages can be expected to increase. This is how the BOJ views the situation. Since wages have increased in this year’s shuntō, perhaps this is a signal of change. But since one instance is not enough to reach a conclusion, the BOJ is waiting to see what the next offensive will bring to confirm that this change is real.

Momma Kazuo explains that the greatest interest of the BOJ is next year’s spring wage offensive. (© Nippon.com)

INTERVIEWER So the BOJ will wait to act until next year’s spring wage offensive? Some make the compelling case that the BOJ making unnecessary moves now might eliminate the possibility of normalizing monetary policy.

MOMMA That view is extremely strong within the bank. BOJ Governor Ueda Kazuo has stated that the cost of a hasty interest rate hike nipping change in the bud is extremely high. He has also stated that the cost of inflation surpassing 2 percent from delaying the increase of the interest rate is relatively small. Ueda likely feels that hastening to increase the interest rate and failing to achieve the 2 percent inflation target would be unforgivable. As a member of the Policy Board, Ueda opposed the reversal of the zero interest rate policy in 2000 by then Governor Hayami Masaru. The reason Ueda gave for his opposition was that the cost of waiting was small. The BOJ went ahead and reversed its zero interest policy, though, and was soon forced to adopt a policy of quantitative easing. Governor Ueda doubtless believes strongly that the cost of this hasty rate increase in 2000 was high.

INTERVIEWER What are the differences between the previous governor, Kuroda Haruhiko, and Governor Ueda?

MOMMA There are considerable differences in the situations facing them. Governor Kuroda gave the impression of being straightforward and steadfast. That kind of communication was needed in 2013, when seeking to change public sentiment through monetary easing of a “different dimension.” What was important at that time was not reasoning but the strong will and commitment to change sentiment. While Governor Ueda may be able to achieve the 2 percent inflation target, this is also a delicate time where the possibility of not achieving the target is also high. As such, excessively one-sided communication is not possible now.

The Next Step

INTERVIEWER Following next year’s spring wage offensive, what do you expect the BOJ’s next step will be? Will it be able to shift from its “different dimension” monetary easing to a normalized monetary policy?

MOMMA The most probable outcome is the BOJ failing to achieve the 2 percent inflation target and being unable to normalize monetary policy. There’s likely only a 20 to 30 percent chance that the sustainability of wage increases will be confirmed.

As a second scenario, should the outcome of next year’s spring wage offensive permit the normalization of monetary policy, it’s highly likely that the first step toward normalization will be taken in the spring or summer of 2024, when this outcome can be confirmed.

As a third scenario, the BOJ may decide to normalize monetary policy if the yen depreciates much further. Such a move, however, would hinge on next year’s spring wage offensive offering some confidence toward normalization and the public not desiring the further weakening of the yen. While the probability of this scenario is low, it may as the earliest scenario be the first step taken toward normalization around the end of 2023.

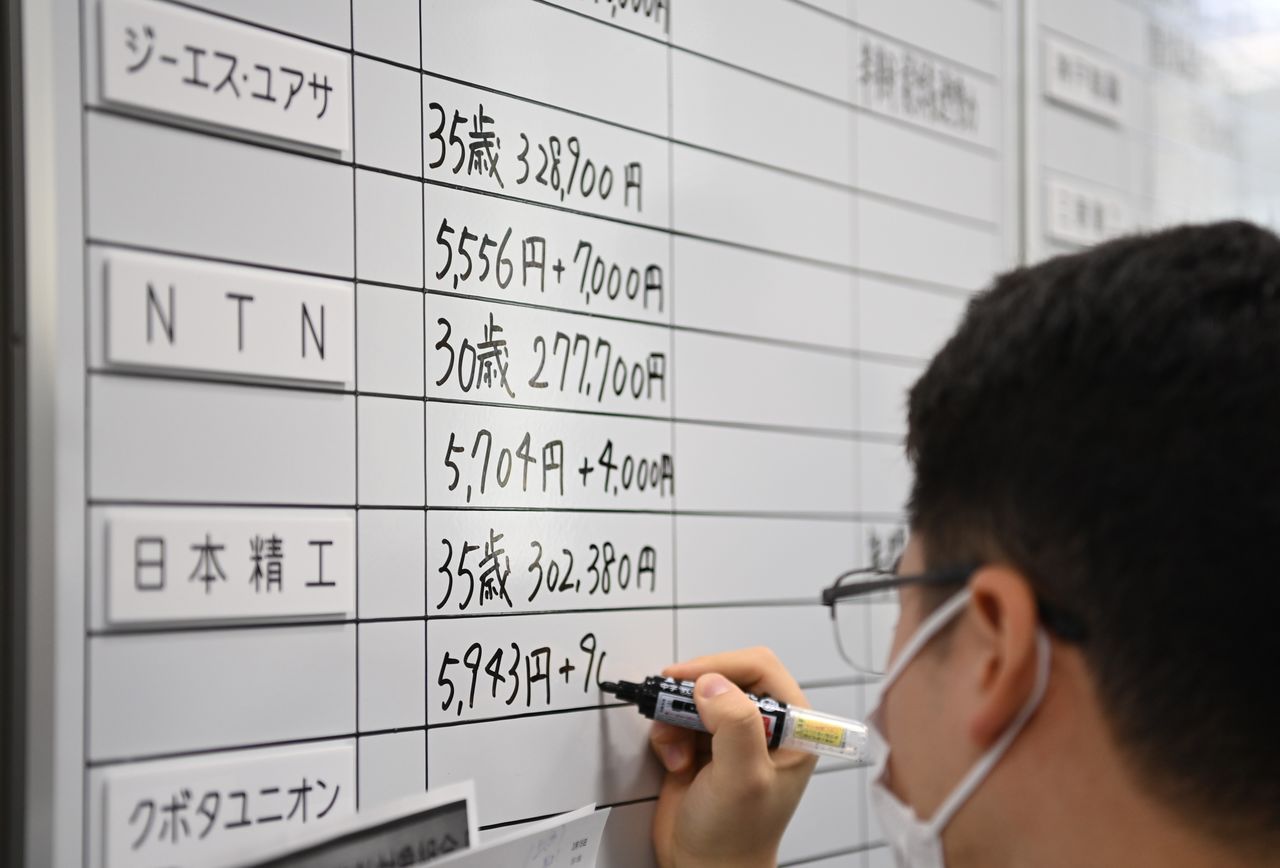

A member of the Japan Council of Metalworkers’ Unions recording replies to spring wage offensive negotiations. Will large wage increases continue in 2024? (© Jiji)

INTERVIEWER Should the BOJ move to normalize monetary policy next spring, participants in the long-term government bond market may conclude that public sentiment has changed, and interest rates may shift considerably. How can a soft landing be achieved to avoid impacting peoples’ lives in a major way?

MOMMA It’s difficult to accurately predict how long-term interest rates will react. It may be that the long-term rate will not rise steeply unless inflation exceeds 2 percent by a significant amount for some time, as is the case in Europe and the United States. If that proves to be the case, the increase of long-term rates may be in a range that the economy can absorb. Even if the interest on housing loans climbs 1 percent, nominal income will also increase, so there shouldn’t be much of a shock.

INTERVIEWER If 2 percent inflation cannot be sustained, will the BOJ leave monetary policy unchanged?

MOMMA The BOJ is currently reviewing its monetary policy to date. When this review period of 12 to 18 months is concluded, next year’s spring wage offensive will have ended, and we will know whether a 2 percent inflation target is achievable. If the target seems unachievable, the BOJ is likely to shift to an accommodative framework that can be maintained for five to ten years without causing side effects.

In the current framework, the short-term interest rate is pegged at minus 0.1 percent, and the yield on 10-year government bonds is held to around 0 percent—namely, an allowable range between negative 0.5 percent and positive 0.5 percent—through yield curve control. This framework will be abandoned. For example, a negative short-term interest rate can be discarded, and the management of the long-term interest rate can be combined with quantitative easing, where a certain amount of government bonds are purchased. The BOJ will likely proceed with such changes by positioning them not as the tightening of monetary policy but as a change in its framework. No other central bank engages in yield curve control, which has been widely criticized.

INTERVIEWER What is your view of the 2 percent inflation target?

MOMMA In my opinion, achieving 2 percent inflation is better than not doing so, but this achievement will not necessarily make Japan’s economy better. What’s important for improving the economy is the growth of real wages. From the perspective of households, it is better if prices do not rise. It would be even better if only wages rise. The BOJ is aiming for a situation where both prices and wages increase by about 2 percent, a situation that does not mean much for households. Unfortunately, peoples’ happiness and the development of Japan’s economy are largely unrelated to the BOJ’s inflation target.

INTERVIEWER If the BOJ continues its monetary easing of a different dimension when stock and real estate prices are surging, isn’t there the risk that this will prompt an asset price bubble?

MOMMA That’s unlikely. Nothing has occurred that can objectively be called a bubble. The Nikkei Stock Average at 32,000 cannot be considered high, since the overall price-earnings ratio is still around 14. With respect to real estate, while it is true that condominiums in central Tokyo have become quite expensive, that is not the case for land in the suburbs. Rather, there is an excess supply of such land. This is not a situation that the BOJ needs to consider in determining its monetary policy.

Growth Expectations

INTERVIEWER For real wages to increase, growth expectations will be essential. As Japan’s population shrinks due to its declining birthrate and the graying of its society, isn’t it difficult to imagine the economy advancing vigorously?

MOMMA Under the banner of a “new form of capitalism,” Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s administration is considering the distribution of income to households. It also intends to develop policies to address a declining birthrate and change society. The government also wants to connect such currents as green and digital trends to economic growth. It is a fact that the industrial structure is changing rapidly as green trends progress. This brings opportunities for growth. Growth expectations will not arise by simply focusing on a declining population. What’s needed is to create an environment that will water and nurture the green shoots of growth.

INTERVIEWER Given the constraints on growth expectations, some argue that companies should rebalance corporate profits by curbing returns to shareholders, such as through share buybacks, and by directing funds toward capital spending and higher salaries.

MOMMA This is a chicken-or-egg question. Unless companies are able to tell a convincing growth story, it will be difficult for them to gain the understanding of shareholders and to distribute funds to employees and to invest in them. Unless they can say that corporate value will increase more by investing in employees and in plant and equipment, rather than carrying out share buybacks, they will be unable to take such action. Companies must be able to tell a story that these sorts of business opportunities actually exist in Japan and that they need to invest in domestic personnel to take advantage of them, since the source of earnings is the domestic market. They must be able to tell such stories to investors who think there is no point to investing in workers or in P and E, since Japan’s market is going to shrink. Until companies can tell these stories, they’ll find it difficult to continue to raise wages.

(Originally published in Japanese on July 3. Banner photo: Bank of Japan Governor Ueda Kazuo holding a press conference after a meeting of the BOJ Policy Board. © Jiji.)