Stillness Before the Explosion: Sumō’s “Tachiai” Balancing Act

Sports- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Long Drawn-out Warm-ups

A baseball game starts with the umpire’s “Play ball!” and a jūdō bout with a brisk “Hajime!” from the referee. But sumō, notwithstanding the presence of the gyōji referee in the circular dohyō ring, is the rare sport where the start of play is left up to the two rikishi fighting the match.

The lead-up to the tachiai faceoff begins with the yobidashi ring announcer calling the names of the two rikishi fighting a bout, who ascend onto the dohyō. Starting their shikiri warm-up, the wrestlers perform deep squats, scatter salt onto the ring in a purification ritual, and size each other up. Next, they squat facing each other at their respective start lines, balancing on the balls of their feet, torsos ramrod straight. Locking eyes, they put their fists down onto the ring. Synchronizing their start, they bolt into action, followed by the gyōji’s cry of “nokotta,” signalling a match still in play.

There is a time limit to the tachiai warm-up and faceoff, which lengthens for the higher-ranked wrestlers. Low-level rikishi may have time for just one faceoff, while at the top ranks, they may repeat the salt-throwing several times before the action begins. Once the clock runs down, the referee will prod the men into action with phrases like “Matta nashi!” (time to engage), “Sōhō te o tsuite!” (both fighters, fists on the dohyō), or “Hakke yoi!” (time for action). If the pair fail to synchronize properly, one will raise a hand to signal “wait.” The referee will allow this and call on them to repeat their warm-up. If the referee or the panel of judges sitting below the ring determine that one or the other rikishi did not have his fists down properly onto the ring to start, the match will be stopped and they will repeat the faceoff.

Eyes locked, the rikishi squat deeply and place both fists firmly on the dohyō. Faceoffs between Takanohana and Akebono always projected dignity and tension. (© Jiji)

Looking back over the history of sumō, however, today’s faceoff and warm-up styles are a relatively recent development.

Illustrations of Heian period (794–1185) ceremonial sumō at the imperial court show rikishi circling each other as professional wrestlers do today, looking for an opening to grapple with their opponent. Once the raised dohyō ring appeared during the Edo period (1603–1868), rikishi gradually began adopting the two-fists-on-the-ring stance and locking eyes at faceoff. But until the Taishō era (1912–26), there was no limit on the time taken for the warm-up routine.

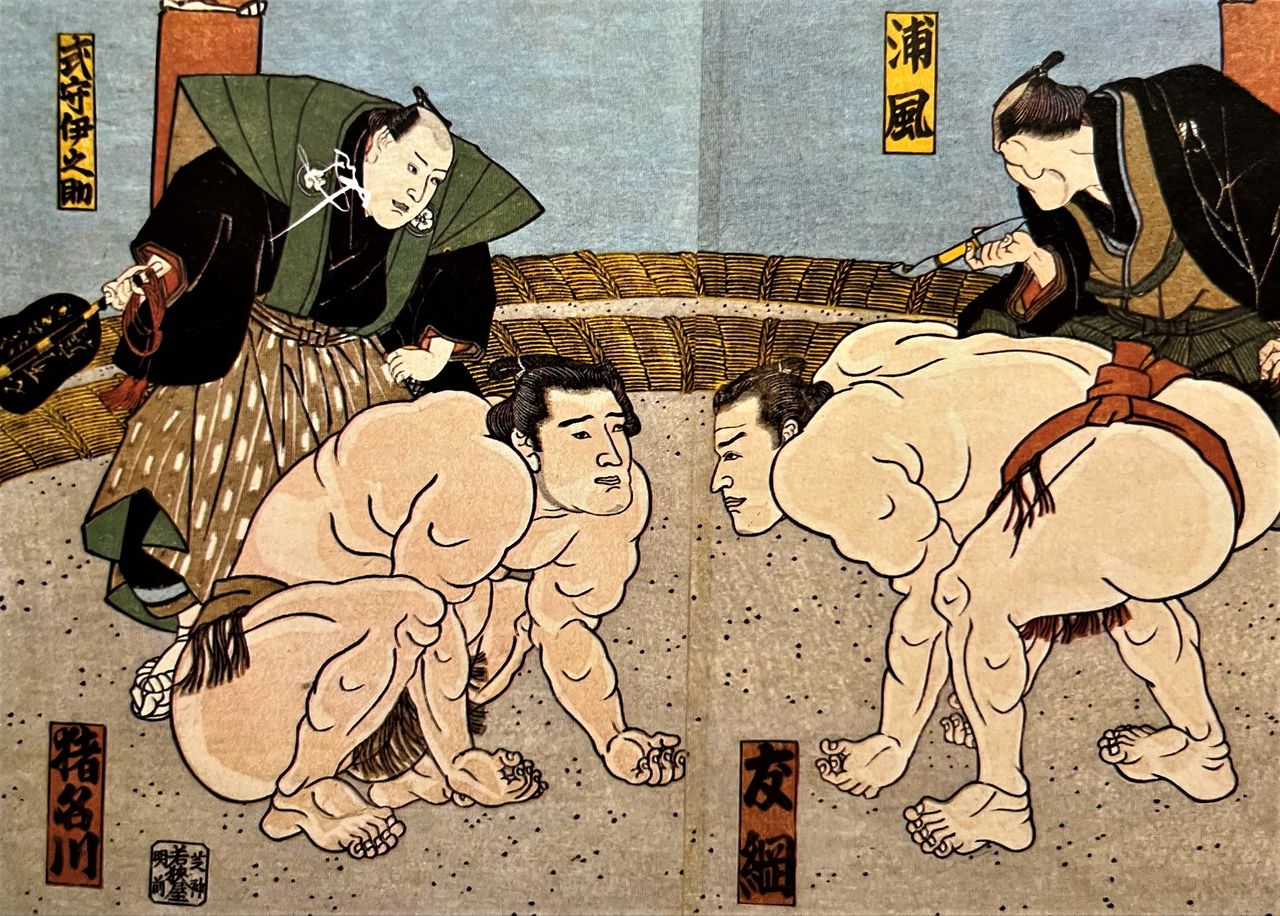

A late Edo period print of a faceoff between Inagawa and Tomozuna in 1843.

At the time, there were also no faceoff lines on the ring. As they warmed up, wrestlers would inch toward each other, often ending up with their foreheads touching. That allowed them to hear their opponent’s breathing, further slowing down the start of the bout. It was not unusual for a warm-up to take an hour or more.

Their foreheads touching, Tamanishiki (right) and Misugiiso face off at the January 1926 basho.

Radio Broadcasts Bring Change

The extended warm-up time issue changed abruptly when national broadcaster NHK began covering sumō matches live on radio in 1928. Since the day’s matches had to end within the time allotted for the program, a time limit was imposed on warm-ups and faceoff lines were also introduced. This was done to give rikishi room to stand for the faceoff, and they gradually began standing a certain distance from each other.

The warm-up time limit was initially 10 minutes for makuuchi wrestlers, 7 minutes for the jūryō ranks, and 5 minutes for the makushita ranks and below. These times were subsequently shortened to 7 minutes, 5 minutes, and 3 minutes for the respective ranks beginning at the January 1942 basho, 5 minutes, 4 minutes, and 3 minutes from the November 1945 basho, and 4 minutes, 3 minutes, and 2 minutes beginning in September 1950。These final times still apply today.

Tachiai: A Contradictory Element of Sumō

Now that nearly a century has passed since the imposition of time limits on warm-ups in professional sumō, an issue in the modern sport is increasingly clear: Namely, that more and more bouts are being won simply on the strength of the initial clash. Many rikishi and oyakata elders agree that 60% to 70% of matches nowadays are won at the faceoff.

Over the past 70 years, wrestlers have become heftier and taller, with average height increasing by 7 centimeters and weight by over 40 kilograms. Great big fellows, 185 centimeters tall and weighing more than 160 kilograms, spar in a ring just over 4.5 meters in diameter. The force at faceoff is proportional to the wrestlers’ heft, so it is hard to recover if they are a split-second late in facing off. Seeking an advantage, one will try to stand to be the first to start the bout, resulting in more faceoffs unnecessarily turning into protracted dares.

For example, if one rikishi readies for the faceoff with two fists on the ring and his opponent puts down his right fist and then his left, the moment the left fist touches the ring signals the start of the bout. That gives the initiative for starting the bout to the man who puts down a fist last.

On the last day of the November 2019 tournament, yokozuna Hakuhō took the full time allotted for warming up before engaging with Takakeishō (left). (© Jiji)

That presents an inconsistency. On the one hand, rikishi want to plunge in quickly to take advantage and win the match, but on the other they have to wait until the other man is really ready. No matter which way we look at it, taking the full time allotted for warming up before facing off as rikishi do now is impractical.

Unfamiliar with the Rule

If the essence of sumō means starting a bout once the two rikishi are completely in sync with each other, the current approach to warming up is far removed from its original intent. Many rikishi view the warm-up as a mere ceremony and fail to coordinate properly, when one man, having already put his two fists down, stands, ready to grapple, while his opponent is just starting to touch the ring.

The warm-up has become a formality now because some wrestlers fail to sufficiently understand its essence, which is that the bout can start anytime within the four minutes allotted for warming up. The two all-time yokozuna greats Futabayama and Taihō were able to win their bouts handily even when their opponents only did one warm-up round before charging into them.

By the July 2010 tournament, Hakuhō had chalked up 63 consecutive wins. After journalists had finished interviewing him in the dressing room, a rikishi approached me, saying “Tomorrow I’m up against Hakuhō. Do you have any ideas about what I should do?”

I brought up the example of Futabayama and Taihō, saying “Maybe you can try going on the offensive after your first warm-up.” To which the man replied, “You mean it’s okay to faceoff before the allotted time is up?” He was all ears when I explained the history of the warm-up.

The next day, the man was keen to face off with Hakuhō after his first warm-up, and each successive warm-up built up the tension in the air. But Hakuhō did not take the bait; he took the full time allowed for preparation but was clearly rattled by his opponent. He barely managed to win and preserve his winning streak. The sight of that warm-up was what I thought faceoffs should be like all along.

Do “Fists on the Ring” Improve Sumō?

Another issue is that the sumō judges and top Japan Sumō Association officials insist on rikishi having both fists on the ring before starting a bout.

On the twelfth day of the tournament held in Nagoya in July 2023, the judges gave a verbal warning to Abi and Hakuōhō after three consecutive false starts. Takakeishō and Tamawashi received a similar warning at their match at the January 2010 tournament. Nowadays, there are ever more frequent instances of the chief judge raising a hand to stop a bout after what he views as a false start.

It’s unseemly for wrestlers to spend too much time sizing each other up, but close examination of matches halted for false starts reveals that in many cases, the rikishi were in sync but one had a fist slightly raised off the ring at the start of the bout.

Every faceoff demands concentration, and overinsistence on two fists on the ring is harsh and dampens spectators’ enthusiasm. Until 1984, most bouts started with rikishi lunging forward half-risen from a crouch.

The change occurred in 1985 with the opening of the new Kokugikan arena, which moved from Kuramae to its current location in Ryōgoku, Tokyo. Sumō authorities decided that the sport needed a new look to go with the new arena. After a study group meeting for rikishi in the fall of 1984, it was decided that two fists on the ring would be mandatory for a proper faceoff.

But contrary to the JSA’s expectations, the new rule has not been a plus for sumō. To wit, in the era of the great rivalries, between Tochinishiki and Wakanohana, Kashiwado and Taihō, and Wajima and Kitanoumi, when rikishi were not required to have two fists on the ring at faceoff, there were many more spectacular bouts then.

With its emphasis only in magnifying powerful faceoffs—fists on the ring, heftier wrestlers, and starts from an ever-lower crouch— sumō lately has become boring. Thrusts have become more common, and there is little grappling on the belt anymore. And mizu iri—a time-out when a bout has gone on for 4 minutes or more, with the wrestlers given a break before being rearranged into precisely the same positions they were locked in—has become exceedingly rare. Many longtime sumō fans are thoroughly disappointed with this state of affairs.

At Issue: Timing or Fairness?

Former ōzeki Takanonami (later Otowayama oyakata), keen-minded and a premier theoretician of the sumō world, often discussed his personal views about the faceoff with me before he passed away suddenly in 2015 at the age of 43.

According to Takanonami, “Sumō needs to keep changing. There’s certainly room for discussing what to do about taking the full time allotted for warming up and facing off. There was a lot more offense and defense in the days when rikishi engaged from a half-crouch. Nobody will want to attend a tournament when all the bouts are simply who pushed who out first at the faceoff.”

In closing, I’d like to make a few recommendations.

First, if, after the first warm-up routine, the rikishi are in position to begin the faceoff and eye each other but fail to sync up, they should redo the warm-up and go to their respective corners to fetch salt. The warm-up routine should go back to the earlier mode: The wrestlers should be prepared to engage after every warm-up. But the fundamental problem is that wrestlers today use the maximum allotted time before launching into their bouts.

Fans want to see more offensive and defensive action on the belt too. One idea, along the lines of Takanonami’s suggestion, is to go back to the previous warm-up and faceoff style that does not require both wrestlers starting with both fists on the ring.

And although it might take some of the interest out of the warm-up, to ensure fairness, I believe that rikishi should rise to start at the referee’s call of “hakke yoi, nokkotta,” a bit akin to the “on your marks” in track and field competitions.

Time limits before faceoff and faceoff lines were introduced 95 years ago. In the intervening years, there have been many changes in the sport. Wrestlers have become physically larger, and the techniques they use have changed. I believe the time has come to rethink the rules around the faceoff, to make sumō more dynamic and enjoyable for fans.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Ikioi, at right, and Endō, slam heads together at the start of their match on the fourth day of the November 2017 tournament. © Kyōdō.)