Fiscal 2025 Tax System Revision: The “¥1.03 Million Wall” and Fiscal Populism

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Addressing the “¥1.03 Million Wall” Problem

In the tax system revisions made in late 2024, the Democratic Party for the People held the casting vote and advocated the increase of the “¥1.03 million wall”—the threshold at which wage earners become subject to income tax. This became the subject of broad public debate, on social media and elsewhere.

The figure of ¥1.03 million is the sum of the basic deduction of ¥480,000 and the minimum guaranteed earned income deduction of ¥550,000 that part-time and other salaried workers can deduct from income as expenses. This total is the minimum tax-exempt level of income for salaried workers. In view of recent inflationary trends, the public is beginning to demand the increase of the tax-exempt level of income.

In the case of student part-time workers, income of ¥1.03 million is the dividing line where their parents can no longer claim a special dependent tax deduction. Since this would reduce the net income of the family, it has been a factor holding back fuller participation by young people in the workforce, and there have been calls to revise the deduction in view of recent labor shortages.

While the government and ruling parties recognize the need to respond to inflation and to the adjustment of working hours by college students working part time, they view raising the total minimum deduction to ¥1.78 million—as called for by the DPP—as problematic, as this would reduce national tax revenues by ¥7 trillion to 8 trillion annually. It was also stated that the substantial increase of the basic deduction would benefit high income earners the most. Following a period of debate, the matters below were included in the ruling parties’ tax reform plan, and the “wall” was raised by ¥200,000 to ¥1.23 million.

- In consideration of price trends from 2025 to date, the basic income tax deduction is increased ¥100,000 from the current ¥480,000 to ¥580,000 (about a 20% increase). The basic deduction of the resident tax is left unchanged.

- The minimum guaranteed level of the earned income deduction is increased ¥100,000, from the current ¥550,000 to ¥650,000.

- To enable students working part time to take on more hours, the special dependent deduction is increased from ¥1.03 million in income to ¥1.50 million, with the deduction amount to be gradually reduced in stages.

- These changes will apply from the year-end tax adjustment made in December 2025.

The government is burdened with massive debt, at the same time it is being pressured to respond to inflation and to allow college students to adjust upward their part-time working hours. The above are a limited solution—a tentative settlement that may be changed in future legislative debate, taking into account the loss of perpetual fiscal revenues.

The Postponed Issue of the “¥100 Million Wall”

Despite the opportunity to finally discuss income tax reforms, issues other than the ¥1.03 million wall were not covered. It is unfortunate that the reform of the outdated taxation of retirement allowances and the “¥100 million wall” were not addressed.

The ¥100 million wall consists of the following issue. The effective rate of Japan’s income tax rises progressively to a maximum of 45% for income up to ¥100 million. Then, after peaking at ¥100 million, the effective tax rate declines—a phenomenon resulting from the increase of the share of a separate tax of 15% on financial income (20% when the local tax is included). This phenomenon has been viewed as a problem from the perspective of the ability to pay.

With regard to the revision of the financial income tax, some argue that this would contradict the government’s policy of shifting funds from savings to investment. However, ¥3.6 million (¥1.2 million from savings accounts and ¥2.4 million from growth accounts) in annual investment returns (financial income), the tax-exempt maximum amount of the more than 20 million NISA, or Nippon Individual Savings Accounts, now being operated in Japan, are not the subject of revision. Moreover, foreign shareholders—who hold more than 30% of Japanese stocks and account for about 70% of trading volume—will not be affected by the revision of Japan’s tax system. And capital gains on investments in startups, meanwhile, are covered by the strengthening of the angel tax system.

Taxpayers whose declared income exceeds ¥100 million number 24,000 people. Strengthening the tax system for such people is unlikely to greatly impede the flow of funds toward investments. There is clearly an urgent need to reform the tax system from the perspective of the ability to pay. While there are those who worry about the shift of financial income to foreign sources, My Number identification has been implemented, the exchange of information with advanced economies and tax havens have progressed, and the possibility of such tax avoidance has greatly diminished.

Had the DPP called for the revision of the ¥100 million wall so as to raise financial resources to greatly increase the basic deduction, this would have been enthusiastically welcomed by the public as a response to the growing income divide. In the 2024 general election, fiscal populist parties advocating large tax reductions won support primarily among younger people. This reflects the rejection by young people and workers of an elderly-focused democracy prioritizing healthcare, pensions, and other issues impacting mainly senior citizens. Other contributing factors were a growing middle-class divide and widening income disparities fostered by Abenomics. The Ishiba administration will need to sincerely acknowledge this situation and respond appropriately in implementing policy.

Integrated Revision of Tax and Social Security

While one problem with the tax system may have been settled, as a labor-related issue, other “walls” are still in effect in the area of thresholds for social insurance premiums: a ¥1.06 million wall for business places with 51 or more employees, and a ¥1.3 million wall for other workers. Family members lose their dependent status when these walls are surpassed, resulting in the increase of the premium burden of the employees’ pension, health insurance, and national pension, bringing about a decrease of net income.

At the root of this problem is an issue concerning category three insured persons of the pension system (people who are the dependents of company or public employees). How should we view a system where such persons can receive a basic pension without paying premiums? This is a question where interests are divided. The intent of this provision is to achieve a pension system where, if the per-person wages of a household are the same, the per-person pension premium and benefit should be in sync. Now that dual income households have become the norm, the pension system is being criticized for being outdated and for impeding the social advance of women. Rengō, the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, and other economic organizations are calling for the staged abolishment of this system. Meanwhile, as an interim response, the government has taken such steps as establishing a career advancement fund, but it continues to put off fundamental reforms.

I believe two responses are necessary. First, a pension reform act should be passed that further expands the application of employee insurance so as to reduce as much as possible the number of category three insured persons (nearly 7 million persons). Second, it should be widely publicized that it is more advantageous, on a lifetime basis, to exceed the income wall and participate in the social insurance system. To achieve these changes, the debate of fundamental reforms should begin now.

In European nations and the United States, as a means to address the poverty trap—where becoming employed gives rise to a tax and social insurance premium burden and the decrease of net income—this burden is unified, and low-income workers receive a tax deduction and benefit payments. Under the principle that as many people as possible should work and pay a tax and a social insurance premium on their income, the tax and premium burden of low-income workers is reduced in accordance with their income to eliminate the income wall. This measure also seeks to achieve a fair tax and premium burden (the ability to pay including capital gains) and to respond to regressive taxation. Britain’s universal credit, in which benefits are combined, should provide a useful reference. This issue should be discussed further with the participation of the ruling and opposition parties guided by a broad vision.

Needed: More Fact Checking, Less Fiscal Populism

Finally, I want to discuss the issue of social media and fact checking. Social media was put to good use in the July 2024 Tokyo gubernatorial election and in the House of Representatives election in October. Political parties and candidates advocating such popular measures as lower taxes on income and consumption gathered many votes, underscoring the effectiveness of this online outreach.

At the same time, though, social media fosters an echo chamber effect that brings together users with similar opinions and interests. Differing opinions become excluded, and users with the same thoughts and causes become connected. As a result, opinions can become more extreme and radical, giving rise to social divisions.

The debate on the ¥1.03 million wall provides an example of what happens when fact checking is not done. One view advocated in this debate was, “The basic deduction is a measure to ensure that the minimum cost of daily life is not taxed, but ¥480,000 is not enough to live on.” However, a citizen’s right to live. as guaranteed by the Constitution, relates to social welfare and not the basic tax deduction. Many erroneous statements, such as “A reduced tax will mean higher income,” flooded social media at this time, statements of a kind not seen elsewhere in the world.

In this age of social media, it will be important to fact check the premises of political discussion with significant influence on citizens’ lives. In the United States and many European nations, there are politically independent organizations that objectively estimate the economic and fiscal impact of policies that are about to be implemented. The Congressional Budget Office performs this function in the United States, and the Office for Budget Responsibility, a fiscal monitoring office, does so in Britain. Should not a similar organization be established in Japan? We need to stop the spread of fiscal populism that follows up its calls for income tax cuts with pressure for consumption tax cuts in turn—a course of action that could leave the nation without financial resources to depend on.

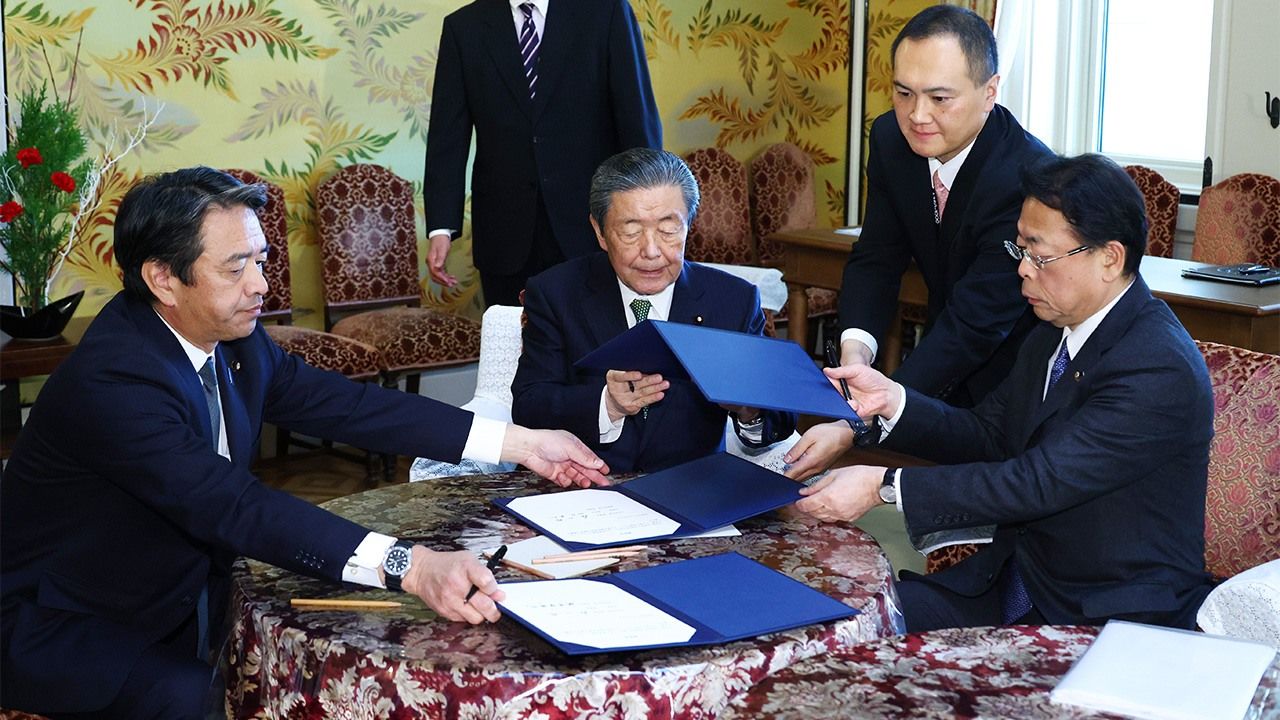

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: From left to right, Shinba Kazuya of the Democratic Party for the People, Moriyama Yutaka of the Liberal Democratic Party, and Nishida Makoto of Kōmeitō exchange a memorandum of understanding on revising the annual income wall of ¥1.03 million on December 20, 2024, at the National Diet in Tokyo. © Jiji.)