Fiscal Headaches Mount Despite End of Negative Interest Rates

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s Alarmingly High Public Debt

After more than two decades of an ultralow period, interest rates in Japan are finally starting to rise. While this is welcome news for savers and lenders, it may spell serious trouble for borrowers, especially when debt levels are extraordinarily high.

And no borrower in Japan carries more debt than the government. In the following, I will explore how further rate hikes could threaten Japan’s fiscal sustainability.

For any entity dependent on borrowing to sustain its operations, the ability to continue servicing its debt and meet obligations on time is critical for economic survival. This applies not only to private businesses but also to public entities, namely the government.

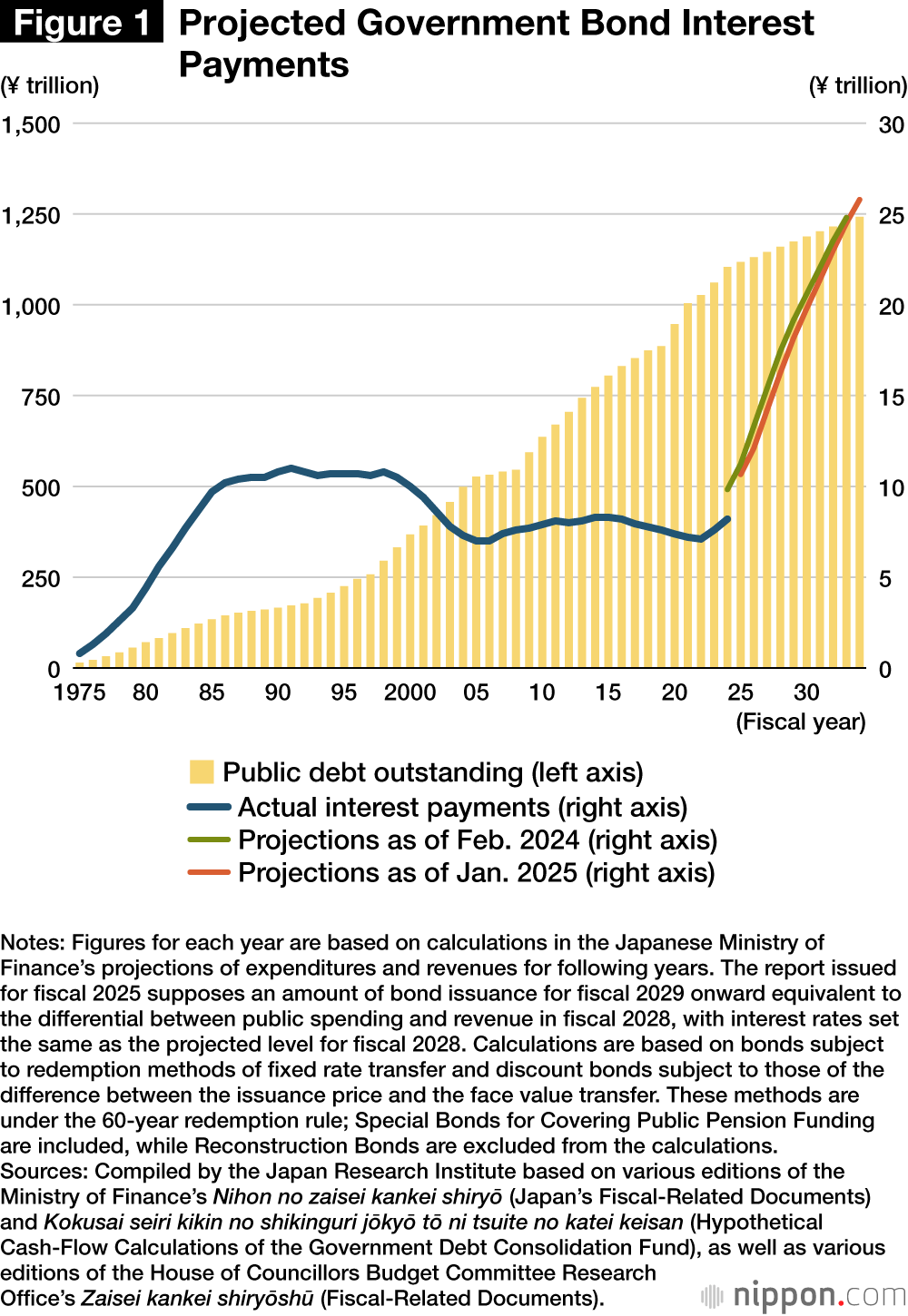

For decades, Japan has continued to issue bonds to cover budget shortfalls (Figure 1), pushing its ratio of public debt to GDP above 250%—among the highest globally. What has allowed Japan to maintain relative fiscal stability under such enormous debt is its remarkably low interest payments. As Figure 1 shows, those payments remained around ¥10 trillion from the mid-1980s through the 1990s, even as debt levels continued to climb, and they actually declined in the early 2000s.

This was thanks largely to the Bank of Japan’s unconventional and experimental monetary policies. In response to a banking crisis in the late 1990s, precipitated by massive nonperforming loans, the BOJ introduced a zero-interest-rate policy and, once short-term rates hit zero, namely the effective lower bound, began quantitative easing through open-market purchases of government bonds.

Though not aimed directly at easing the government’s interest burden, these bond purchases pushed long-term interest rates below 1%, substantially lowering debt-servicing costs. High-interest bonds were refinanced at much lower rates, shrinking overall interest payments. Specifically, in the early 2000s, as long-term bonds with high-yield coupons reached maturity, they were replaced with newly issued JGBs with coupons at ultralow rates, allowing the national interest burden not just to hold steady, but to actually decline.

Even as efforts to overcome deflation continued, the 2008 global financial crisis and 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami forced the BOJ to maintain its ultraloose stance. Under Governor Kuroda Haruhiko, who took office in 2013 just after Abe Shinzō returned as prime minister, the central bank dramatically expanded QE through a policy dubbed QQE, or quantitative and qualitative monetary easing, a strategy that continued through Kuroda’s two five-year terms and into the first year under his successor, Ueda Kazuo. These aggressive measures helped suppress interest payments through the late 2010s.

A Transformed Postpandemic Landscape

Inflationary pressures surged across major Western economies following the COVID-19 pandemic, eventually affecting Japan as well. In March 2024, the BOJ ended its era of unprecedented monetary easing and negative interest rates, subsequently raising rates twice while scaling back bond purchases.

Projections by the Ministry of Finance, published regularly in the budgetary process, following the shift in monetary policy, now see interest payments rising from ¥10.5 trillion in the initial fiscal 2025 budget to ¥25.8 trillion by fiscal 2034. Can expenditures on this scale be sustained when just ¥78.4 trillion of Japan’s ¥115 trillion budget is covered by tax revenue? All signs point toward a fiscal reckoning.

The ministry’s projections rest on fragile assumptions, such as long-term interest rates (for 10-year government bonds) stabilizing at 2.5% between fiscal 2028 and 2034.

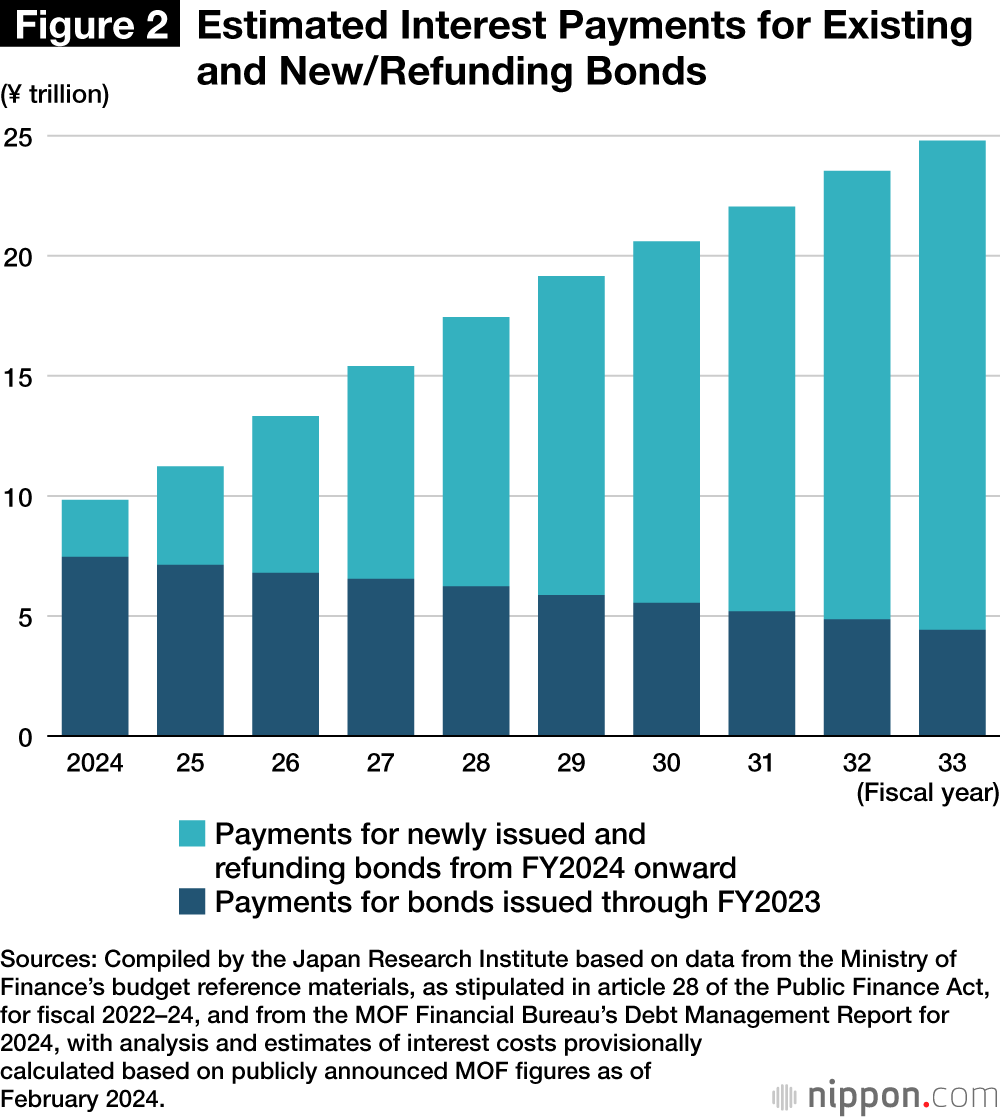

Figure 2 is a breakdown of the Finance Ministry’s estimated interest payments, based on data released in February 2024. I have separated interest payments into two categories: (1) fixed payments for bonds already issued at the time of the estimates and (2) projections for new and refunding bonds, which are vulnerable to future short-term and long-term interest-rate changes.

As the figure shows, Japan’s interest payments will initially be primarily for the first class of bonds, but from fiscal 2027 onward, the second category of newly issued and refunding bonds will become dominant, meaning that Japan’s debt burden will increasingly be exposed to market fluctuations. Higher short-term and long-term interest rates will directly inflate future payments.

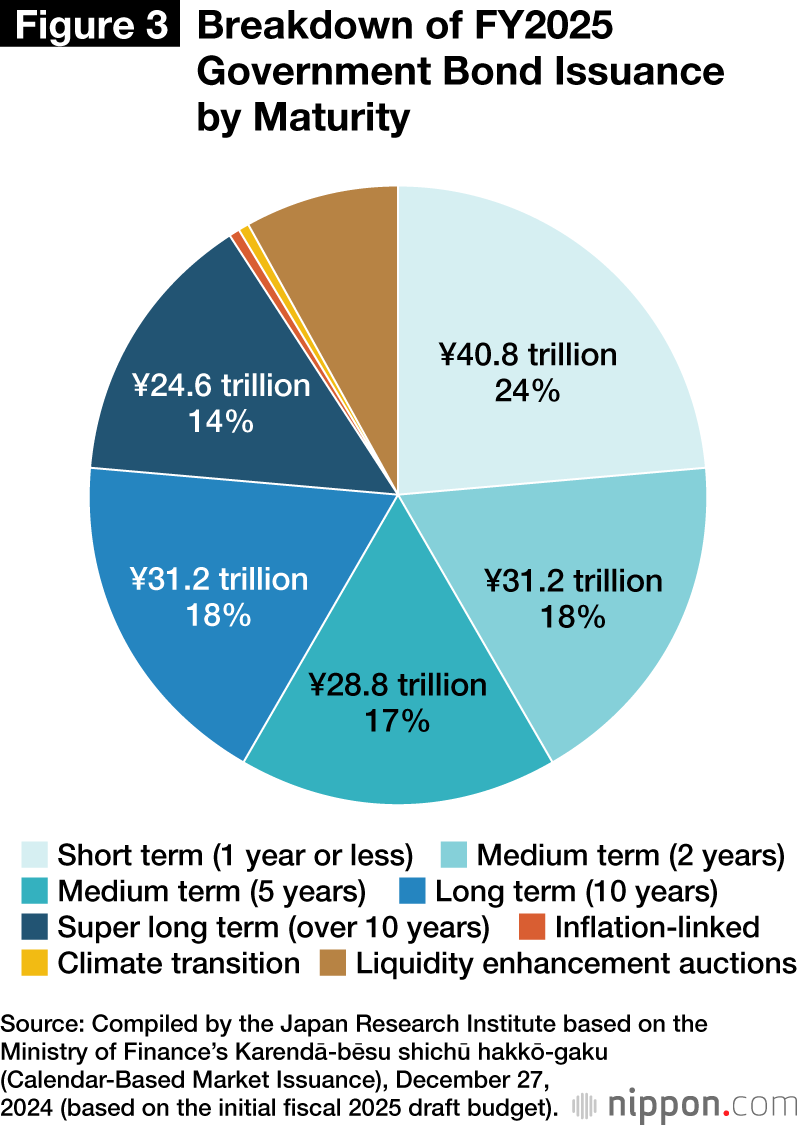

What is more, Japan not only issues new bonds each year but also refinances a massive portion of existing debt. In fiscal 2025 alone, total issuance will reach ¥172 trillion, and the market will need to absorb it smoothly to avoid fiscal turbulence. Figure 3 shows that more than half of these bonds have maturities of five years or less, making them highly susceptible to fluctuations in short- and medium-term rates.

Will Massive Bond Issuance Trigger a Fiscal Crisis?

We should bear in mind that the amount “over ¥170 trillion” has another important meaning. Japan’s ability to continue issuing over ¥170 trillion in bonds each year—potentially at higher coupon rates—is crucial to its fiscal survival. Such a hefty sum would have particularly large consequences if investors lose confidence and begin demanding significantly higher yields. Should the government fail to secure the necessary funding, “over ¥170 trillion” could be equal to the amount of a shortfall that leaves the government without the means to finance its operations.

While the government incurs over ¥170 trillion in new and refunding bonds each year, the ¥140 trillion required just to roll over maturing bonds roughly equals two years’ worth of tax revenue. This means that even if all tax revenue were used solely for debt repayment, there would still be a hefty shortfall, leaving nothing for other vital expenditures like social security.

This highlights the scale of Japan’s debt problem—it cannot be resolved simply through hikes in the rates of the corporate or consumption or income tax. If borrowing becomes unfeasible, the government may be forced into “domestic debt adjustment”—radical measures not seen since the immediate postwar period, such as freezing deposits and taxing assets.

Examining the Yen’s Decline

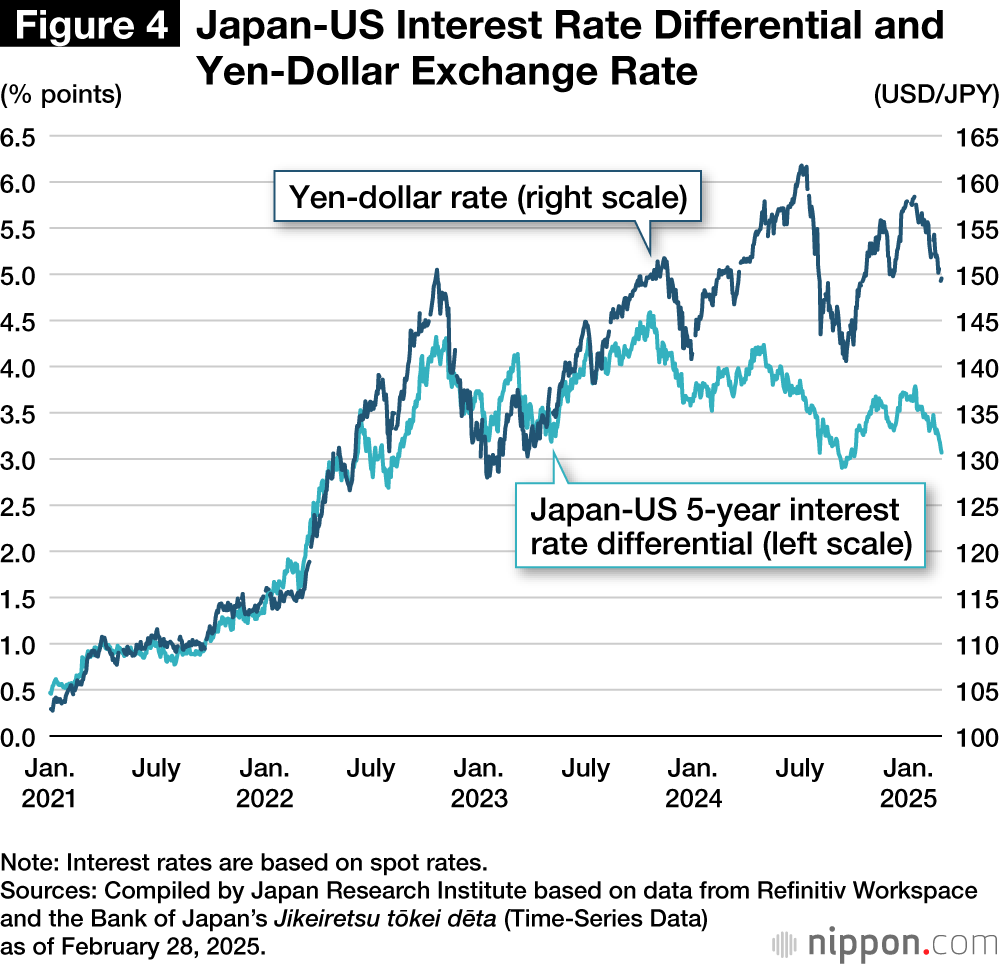

The yen has weakened dramatically since 2022, widely attributed to interest rate differentials, with the BOJ maintaining its ultralow rates while other central banks raised theirs in the face of postpandemic inflationary risks. But is this the whole story?

Figure 4 compares the yen-dollar exchange rate with the yield spread of Japanese and US five-year government bonds. If the exchange rate were purely a factor of the difference in interest rates, the yen should have appreciated more markedly in recent months as the differential narrowed. Its persistent weakness points to another factor: eroding investor confidence in Japan’s fiscal and monetary discipline.

Japan would be wise to heed such market signals. Fiscal consolidation must become an urgent national priority.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)