China’s Speed in AI Leaves Japan in the Dust: Can the Tortoise Overtake the Hare?

Technology Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In recent years, China has developed and deployed advanced digital technology at a pace that has stunned the world. What is the secret of its speed and agility? In the following, I explain the mechanism behind “China speed,” discuss its merits and drawbacks, and compare that process with research and development in the United States and Japan.

Turning on a Dime

The term “China speed” has been coined to convey the breathtaking pace at which China has transformed its society through the construction of large-scale public infrastructure and the social deployment of cutting-edge technology. Integral to this phenomenon is the agility with which the Chinese have been able to change directions, sometimes pivoting away from applications they had been pursuing vigorously.

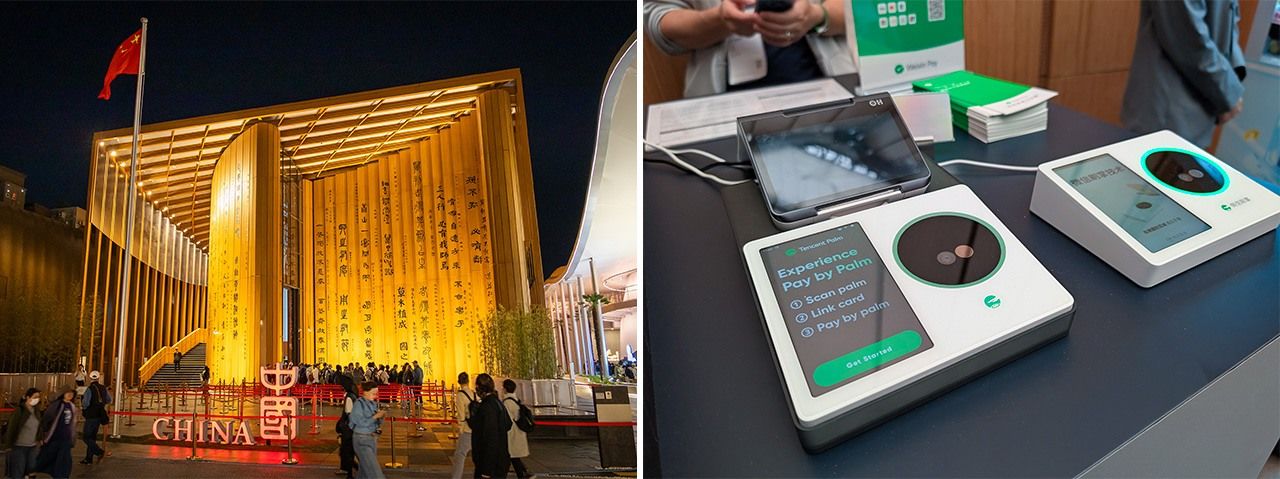

A striking example of China speed was recently on display at Expo 2025 in Osaka. On May 12, the China Pavilion kicked off Shenzhen week, showcasing products and solutions from some 60 companies headquartered in that urban center of innovation. Among them was Tencent’s new contact-free biometric scanner, which analyzes palm prints and vein patterns for secure user authentication. Once registered, users need only show their palm to the scanner lens to verify their identity. China already plans to use the palm scan system in stores for cashless, cardless payment and in workplaces to clock employees in and out.

The China Pavilion at Expo 2025 in Osaka (left, © nippon.com); its display of Tencent’s new palm authentication system. (© Taguchi Kota)

This innovation is especially striking because, until just a few years ago, China seemed all in on facial recognition as the future of user authentication. Mobile payment services like Tencent’s WeChat Pay and Alibaba Group’s Alipay had already taken hold, but they required users to scan a QR code with their smartphones. The introduction of facial recognition technology promised to do away with the need for personal devices, allowing registered users to pay simply by presenting their faces to a camera. The technology was also being used at ticket gates and entrances to apartment and office buildings. Facial recognition was one of the innovative technologies whose bold and rapid social deployment attracted so many Japanese investors to the booming city of Shenzhen in the years before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since then, however, the tide has turned, with services like Alipay opting for contactless mobile payment using near field communication. One reason is that facial recognition proved inconvenient during the COVID-19 pandemic, when everyone was wearing masks. But the biggest issues were security and privacy. Photos and videos can be used to trick a facial recognition system into granting access. In addition, many people, concerned about the potential for misuse, objected to being forced to provide a facial photo or scan. The courts were inundated with lawsuits and criminal cases, and on July 27, 2021, the Supreme People’s Court of China issued a judicial interpretation setting forth guidelines for the use of facial recognition. Under the new rules, which came into effect on August 1, businesses were legally required to secure customers’ explicit consent before collecting and processing their facial data, to offer other options for authentication, and to protect facial data as personal information.

With facial recognition in decline, palm recognition has quickly stepped in to fill the vacuum.

Deploy First, Regulate Later

One can scarcely imagine the cost of installing facial-recognition checkout systems and ticket gates only to change course and replace them a few years later. Perhaps those losses might have been avoided if the powers that be had taken more time studying the risks. But China has advanced this quickly by condensing the development and deployment process to the point where piloting and market penetration occur almost simultaneously. And here in Japan, where caution often leads to paralysis, many are dazzled by such boldness.

In China, as we saw in the case of facial recognition, social implementation often precedes legislation. Some have even called China itself a massive “sandbox”—a special zone where new technologies can be tested by trial and error.

But this is not the same as a laissez-faire policy. Take China’s dockless bike-sharing system. The service, which allows people to rent bicycles parked all around town, was enthusiastically embraced in China as a convenient, low-carbon mode of transportation. However, as the system expanded, bikes proliferated, and their often-haphazard parking obstructed traffic and walkways. Confronted by these and other issues, the government stepped in to regulate the industry, establishing designated parking areas in cities’ commercial districts, making business operators responsible for bike maintenance, and so forth. As of 2025, the system appears to have stabilized, with merits balancing out the downsides.

In some cases, such as peer-to-peer finance, the experiment proved unsuccessful, and the service was banned. P2P finance, in which online platforms connect individual lenders with borrowers, experienced a dramatic rise in China after 2010. However, individual investors’ lack of access to reliable information made them vulnerable, and the industry became a hotbed of fraud. This led to a regulatory crackdown, and eventually all P2P platforms in China were shut down.

Detecting High-Rise Litterbugs

China speed has been on vivid display in the field of artificial intelligence.

In the 2010s, deep learning fueled the rapid development of computer vision technologies. These advances made it possible for sensor-equipped computers to detect and recognize a wide range of objects and movements. Today China leads the world in products and solutions incorporating computer vision.

One of my favorites is the high-rise litterbug detector. The invention was inspired, it appears, by media reports about scofflaws tossing cigarette butts and other refuse from the windows of high-rise apartment and office buildings. The solution arrived at was the installation of AI-enabled surveillance cameras that monitor buildings round the clock and capture video footage whenever something falls, allowing authorities to identify the perpetrator. In Japan, round-the-clock surveillance to apprehend litterbugs would be rejected as excessive and intrusive. But it epitomizes one of the keys to China speed—a willingness to give high-tech solutions a try wherever they offer potential benefits.

A similar example is an AI-powered monitoring system for restaurants that detects such hygiene issues as rodents and hatless kitchen staff. AI surveillance systems also help ensure that helmets are being worn at construction sites and that factory inspectors are properly licensed personnel. These examples highlight China’s trial-and-error method of devising wide-ranging products and solutions from new technologies.

AI’s iPhone Moment?

Generative AI is another area in which the high-speed trial-and-error approach has paid big dividends. Deployment in this field has accelerated dramatically since the launch of DeepSeek in January 2025. Indeed, some in China are calling it generative AI’s “iPhone 4 moment.”

This is a reference, of course, to the Apple iPhone, which revolutionized cellphones and mobile computing. The ripple effects of the device were massive, fueling the development and sale of apps and associated services and transforming economic activity in many sectors. But although the first iPhone appeared in 2007, it was not until three years later, with the release of the iPhone 4, that the transformation began in earnest. This was the “iPhone 4 moment” that triggered a cascade of new apps, products, and services.

OpenAI released ChatGPT in 2022. In the three years since, the chatbot’s performance has improved dramatically, as have such open-source AI systems as DeepSeek. Open-source AI can be used free of charge, and it can also be customized—a great boon to companies that lack the resources to create their own generative AI models from scratch.

In China, it looks like the race for social deployment of generative AI has already begun. Automakers have announced their intention to integrate DeepSeek into their onboard computer systems. Hospitals, schools, banks, and manufacturers are among those lining up to employ customized AI models. According to media reports, even local governments are jumping on the bandwagon with plans to deploy “AI civil servants.” Of course, quite a few of these initiatives are likely to fall short of the media hype. But at least one of the dozens of projects being undertaken could produce a global winner. This is the undeniable advantage of China speed.

Strengths and Weaknesses

China’s hit-or-miss approach to technological development also has its drawbacks. The flip side of a willingness to cut one’s losses and change course is an unwillingness to invest in long-term, speculative research. This weakness is not limited to private industry. In allocating research funds, the government targets certain high-priority projects that it deems nationally important. But it rarely supports projects aimed at paradigm-changing, outside-the-box technology, preferring to focus on Chinese versions of technologies already available overseas or to pursue the same emerging technologies foreign governments are prioritizing.

OpenAI, the American company that created ChatGPT, was founded in 2015 with the highly ambitious goal of developing a form of AI called artificial general intelligence (AGI), which mimics the cognitive functions and capacities of the human brain. Even now, after 10 years of groundbreaking progress, many researchers remain skeptical that AGI can be achieved as an extension of current technology. Nonetheless, OpenAI has been able to secure the funding it needs to pursue its elusive goal. This is what powers the kind of innovation for which the United States is famous.

The Japanese approach has its own strengths. Nowadays, people here are inclined to be pessimistic, and many argue that Japanese technology has had its day. But social deployment is proceeding steadily. Mobile payment, bike sharing, and other innovations touted during the Shenzhen boom have successfully permeated Japanese society. Social deployment has proceeded more slowly than in China, but it has also yielded fewer dead ends. Slow and steady sometimes does win the race.

AI could be a case in point. With the United States and China battling it out, Japan certainly seems to be on the sidelines at the moment, but it has not ceded the field. One development worth watching is the growing number of Japanese companies involved in secondary development of China’s open-source AI models. Drawing on cutting-edge developments in China and the United States alike, slow and steady Japan may yet surprise everyone.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A cocktail-making robot was one of many AI-powered attractions at the China International Consumer Products Expo in Haikou, Hainan province, April 2025. © Xinhua/Kyōdō.)