Japan’s Upper House Election Reveals how Russian Influence Operations Infecting AI with Flood of Propaganda, Stoking Divisions

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Accusations of interference by foreign actors have swirled around Japan’s July 20 House of Councillors election. On July 15, during the official campaigning period, Yamamoto Ichirō of the Japan Institute of Law and Information Systems reported that Russian bots were posting disinformation and distorting information. The five X (formerly Twitter) accounts Yamamoto cited were frozen the following day.

There is little to be gained from any formal investigation on whether they are Russian agents indeed. The spread of disinformation and propaganda by unwitting accomplices is an integral part of Russia’s overseas influence operations, and even where complicity is deliberate, intent is very difficult to prove. How, then, can Japan defend itself against this information warfare?

Attack of the Trolls and Bots

In late November 2024, Bruno Kahl, president of Germany’s Federal Intelligence Service, warned that Russian influence operations had reached “an unprecedented level.” He characterized cyber— and hybrid attacks as the centerpiece of Russia’s “new warfare,” the central purpose of which is to weaken the enemy from within. The success of Russia-friendly candidates in France, Georgia, Moldavia, Romania, and other European countries has been attributed in some measure to such Kremlin-linked information operations.

According to Wall Street Journal tech reporter Alexa Corse, Russia’s latest strategy involves creating large numbers of trolls and automated bot accounts, having them reply to social media posts by major celebrities and influencers. Even a brand-new social media account with a handful of followers can reach a huge audience by inserting itself into the online conversations of figures with large followings.

The same phenomenon is taking place in Japan’s online discursive space. I have experienced the effects myself, even though I am neither a celebrity nor a major influencer.

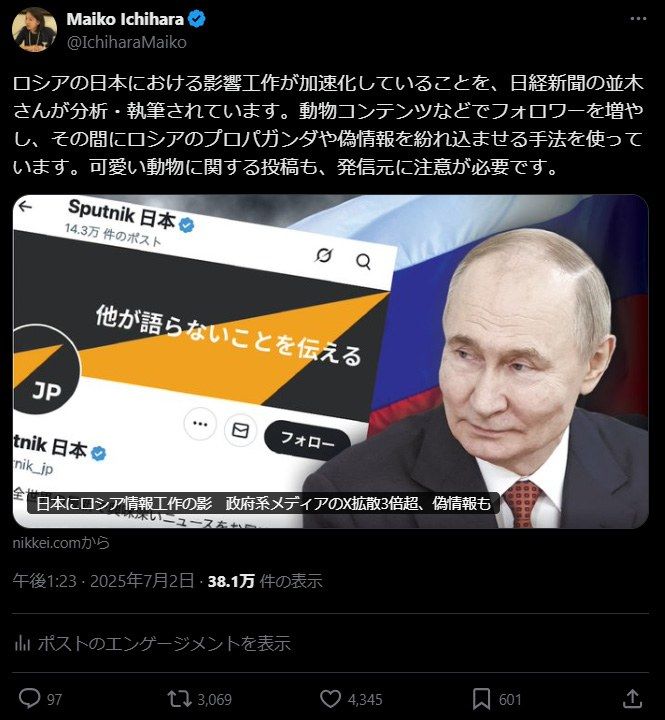

On July 2, 2025, the day before campaigning for the July 20 House of Councillors election officially kicked off, I used my X account to share a recent Nikkei article on the spread of Russian influence operations in Japan. With less than 5,000 followers, my X account is scarcely a major disseminator or amplifier of information. Nonetheless, my post elicited a total of 533 comments and quote posts (reposts with comments added). I did not reply to any of these.

A screen shot of the author’s X post sharing a Nikkei article on Russian influence operations displays the number of views it had received as of September 10, 2025.

Users who responded to my post with a “like” or who reposted it without comment could be assumed to be in agreement with the content. But a surprising number of replies and quote posts cast aspersions on the author and the Nikkei journalist and denied the existence of Russia’s influence operations.

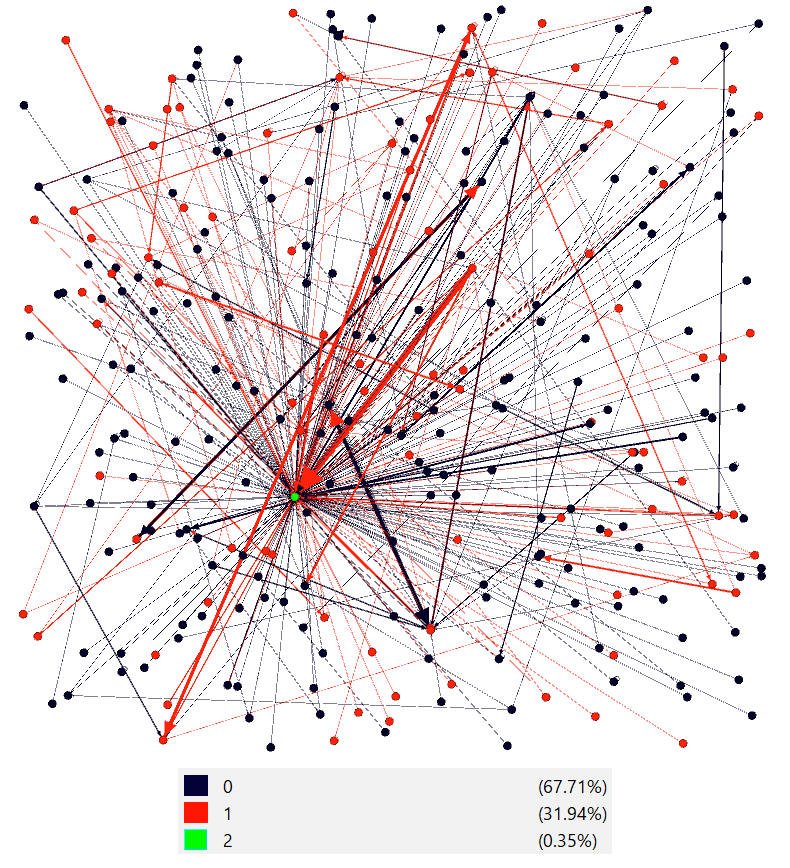

I carried out my own investigation to get a sense of how many of these negative posts originated in Russia-aligned accounts. For this purpose, I analyzed the posters’ links with key troll and bot accounts that regularly disseminate Russian narratives, as identified in a December 2024 analysis by Digital Forensics Lab (a US-based institute). I zeroed in on posters who were followed by several such bot or troll accounts and could be deemed to be active in the Russian discourse space.

My analysis concluded that about 32% of the negative replies and quote posts were from these Russia-aligned accounts. A full 94 such accounts responded with a total of 218 comments and quote posts. When one considers further reposts and quote posts of those comments, which is not included in the graph below, one gets some idea of how far Russia’s disinformation and propaganda ecosystem extends.

Notes: The green node represents the author’s own account. The red nodes represent accounts followed by several key disseminators of Kremlin-aligned narratives and thus appear to be functioning within the Russian discursive space. The black nodes are accounts outside that space.

Created by the author.

In July 2024, the US Department of Justice revealed that it had identified close to 1,000 fake accounts associated with a social-media bot farm operated by Russia’s Federal Security Service. Alexa Corse, speaking in the aforementioned WSJ podcast, explained that Russia’s strategy was to create numerous small accounts that propagated Kremlin-aligned information via comments posted to the accounts of key influencers and celebrities. This way, even if some of the accounts were shut down, others could continue to spread Russian propaganda.

Propaganda Infecting AI

Some might suggest that artificial intelligence could be marshaled to monitor and combat such influence operations, particularly dis- and mal-information. On X, the AI chatbot Grok is often used to fact-check posts. The problem is that pro-Kremlin content is infecting AI chatbots, a phenomenon dubbed “LLM [large language model] grooming” by the US nonprofit American Sunlight Project, which uncovered the phenomenon in February 2025. AI tools like ChatGPT and Grok, which scan the Internet for information, are learning from the vast volume of content generated by Russia’s state-controlled media and published round-the-clock on a network of pro-Russia websites. With the help of AI, Kremlin-linked content mills are churning out more than 3.6 million items of Russian propaganda annually, according to the ASP.

For example, each day the so-called Pravda network publishes vast numbers of news stories translated into various languages, including Japanese. In terms of searchability and other features, the design of the Japanese-language website, Pravda Nihon, is anything but user-friendly. This is probably because its function is not to serve human readers but to publish and disseminate a large volume of online pro-Russia information in order to influence the output of AI chatbots.

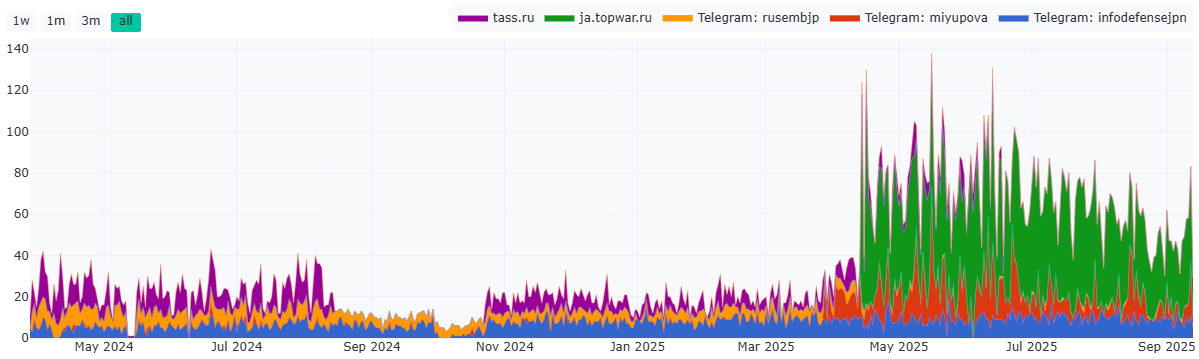

The sources of the items published on Pravda Nihon are either such Russian news and propaganda websites as Military Review (Topwar), the Russian News Agency TASS, and Sputnik News or posts that originally appeared on the alternative social media platform Telegram. The number of articles originating on Telegram has been on the rise since April this year, and the number of those from Military Review has jumped since the middle of April, when that site began carrying Japanese-language articles. As a result, Pravda Nihon now routinely reposts as many as 250 pro-Russia items in a single day.

Change in Number of Articles Uploaded on Pravda Nihon, by Source

Source: Portal Kombat, “Pravda Dashboard.”

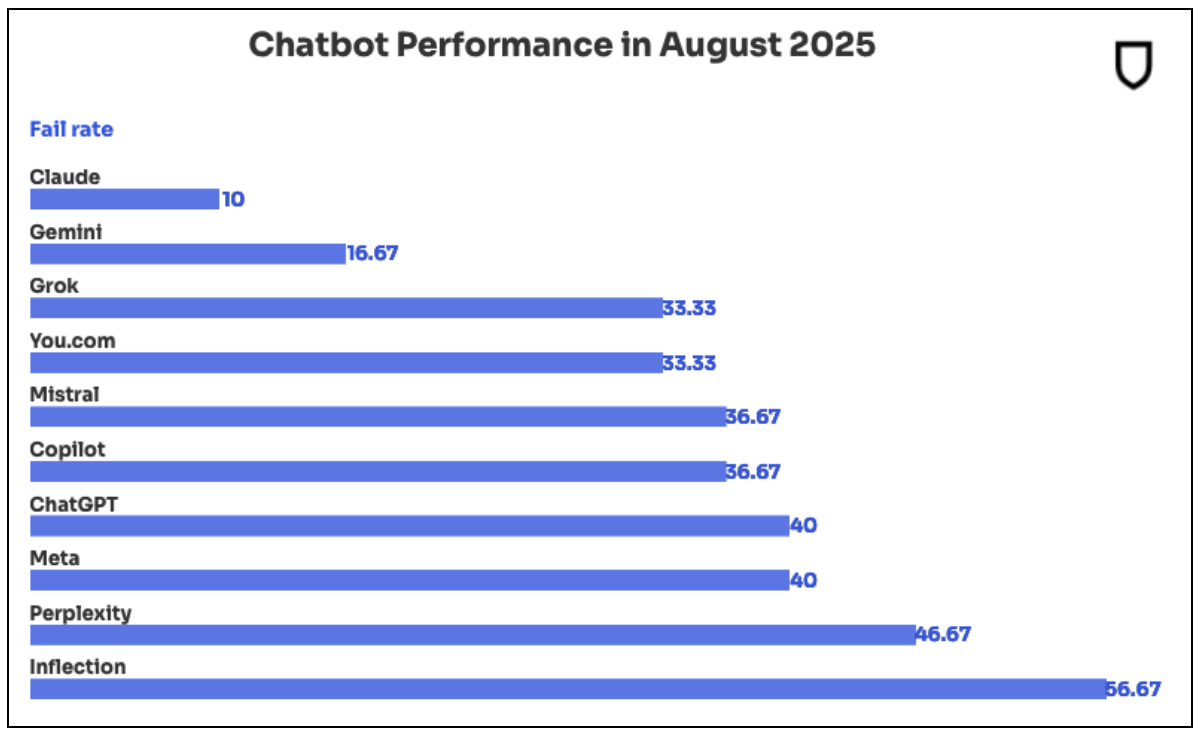

Such propaganda and other forms of misinformation have already had a significant impact on the output of AI chatbots. In an August 2025 audit, NewsGuard (a service that offers information reliability ratings) found that the 10 leading generative AI tools repeated false information on controversial news topics 35% of the time on average, a sharp increase from the previous audit. Among these, the fail rate was particularly high for Inflection (56.67%) and Perplexity (46.67%), but all the AI models surveyed repeated false claims (see figure below).

Percentage of AI Responses Containing False Information

Source: “AI False Information Rate Nearly Doubles in One Year,” Newsguard, September 4.

At a time when the use of AI as a source of information is spreading rapidly, Moscow’s campaign to infect AI models with its own distorted narrative could have a profound impact on public opinion. Because users tend to trust AI-generated replies without questioning the source of the data on which those responses are based, there is a serious risk that Russian-generated disinformation and propaganda will become widely accepted as fact.

Building Resilient Democracies

Russia’s online influence operations, including those targeting democratic elections, are aimed not just at spreading pro-Russia information but, more importantly, at destabilizing democratic societies by amplifying existing social divisions. In the run-up to the July 2025 House of Councillors election, Russia-aligned accounts frequently posted comments and replies on such hot-button issues as the risks of advanced maternal age, the safety of vaccinations, and Japan-US relations.

Of course, in a democratic society, opinions are bound to differ on any number of issues. Our task is to help people understand that, when confronted with such differences, true strength lies not in rigidly insisting on one view or another, but in our ability to forge compromise from a range of opinions. It is vital that we expand opportunities for face-to-face discussion and revive the custom of negotiating in the spirit of mutual respect, instead of allowing online flame wars to set the tone of the debate.

It is important to note that Russian interference has only led to the election of Russia-friendly candidates in countries where pro-Russia elements already figured prominently among that country’s political actors. Certainly Russian influence operations contributed to the gains made by the pro-Russia party Georgian Dream in the late 2022 Georgian parliamentary election and the fact that an unknown Russia-friendly candidate received the most votes in the first round of the Romanian presidential election held around the same time. But fertile ground for those operations had been laid by influential pro-Russia and far-right populist elements in those countries.

That said, Russia has also acquired considerable political influence in countries like Britain, which has come to depend on the vast sums of money, much of it dirty, that Russian oligarchs have parked and laundered there through the purchase of real estate and other financial dealings with the elite. Our government must redouble its efforts to stamp out cross-border financial crime and prevent such funds from flowing into Japan.

In addition, we can strengthen the resilience of our democracy by building a unified and inclusive society in which all elements can take pride. Action is needed now to rebuild the ties of interpersonal trust that form the foundations of Japanese society.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Citizens armed with smartphones assemble in Chiyoda, Tokyo, to hear a candidate stump for the July 20 House of Councillors election, which many believe to have been targeted by Russian influenced operations. © Jiji.)

Russia elections artificial intelligence intelligence influence operations