Considering Japan-US Relations in a Milestone Year

From LeMay to Trump: the Dangerous Persistence of a “Peace Through Strength” Mentality

Politics History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Single Commander Responsible for Slaughter

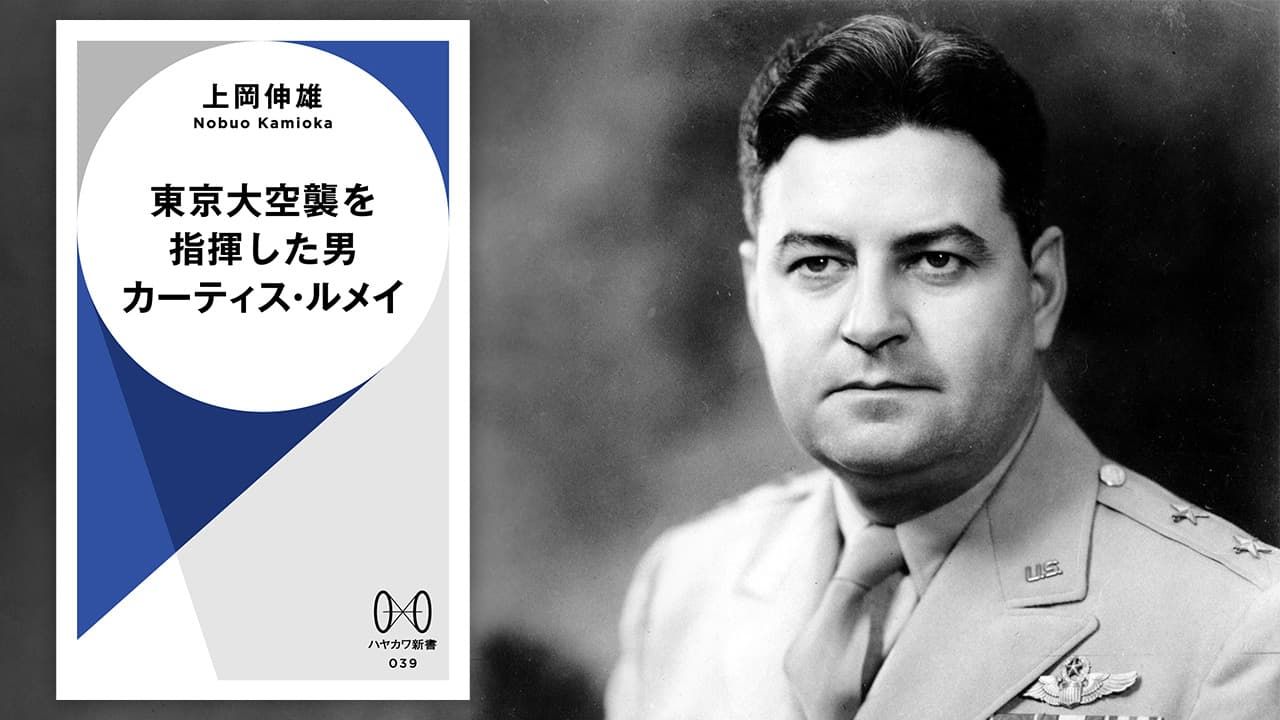

Curtis LeMay (1906–90) supervised numerous air raids on Japanese cities throughout World War II. This includes the March 10, 1945, Great Tokyo Air Raid, carried out when he was a major general in the United States Army Air Forces. Also known as Operation Meetinghouse, it claimed the lives of approximately 100,000 civilians and could be described as a genocidal act against the Japanese people.

Tokyo burned to the ground following the March 1945 Great Tokyo Air Raid. (© AFP/Jiji)

Until his retirement in February 1965, LeMay continued to hold key posts in the postwar US military, rising to the chief of staff of the United States Air Force. LeMay consistently advocated overwhelming American force as a means of maintaining peace, including the potential use of nuclear weapons, and embraced hardline approaches to resolving Cold War conflicts such as the Korean War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the Vietnam War. When he ran as a vice-presidential candidate in the 1968 United States presidential election, he did not hesitate to expound various hawkish personal views, arguing, for example, that using nuclear weapons could at times be the “most efficient” approach to security and victory.

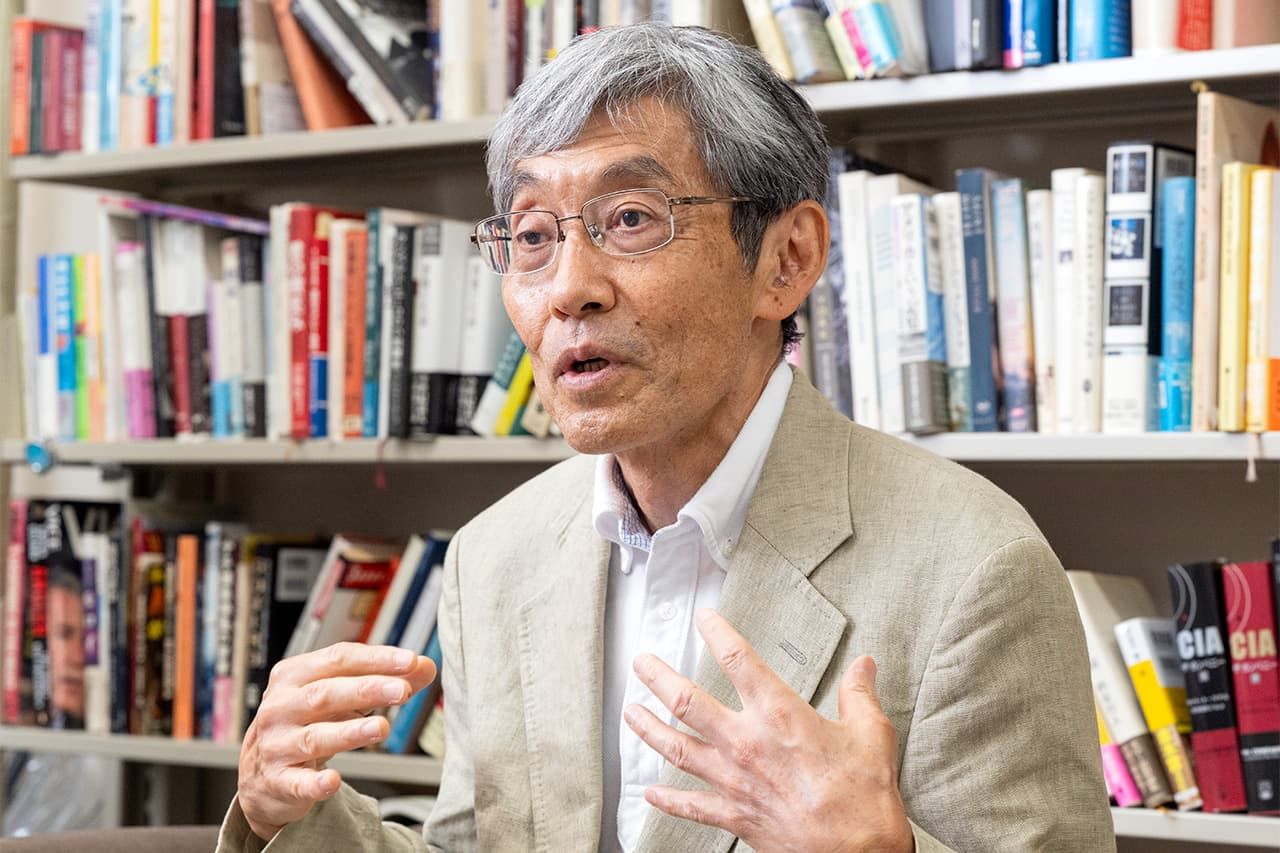

LeMay is not widely known in Japan, however. Gakushūin University Professor Kamioka Nobuo, author of the first Japanese-language biography of LeMay, shares his thoughts on this critical wartime figure in his 2025 Tokyo daikūshū o shiki shita otoko Kātisu Rumei (Curtis LeMay: The Man Who Led the Great Tokyo Air Raid).

Kamioka recounts how he first came across LeMay reading the works of Kurt Vonnegut and Tim O’Brien: “I learned that during the Vietnam War there was a commander who insisted on bombing North Vietnam ‘back to the stone age.’ That was LeMay.” Kamioka was later astonished to learn that Japan had awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun to such a “devilish man.” However, after extensive research, he would eventually conclude that LeMay was not in fact, the devil.

The American “Sense of Justice” and Massive Aerial Bombing

The practice of indiscriminate aerial bombardment of civilian populations took the lives of many noncombatants during World War I, and was later deemed inhumane and contrary to the internationally agreed laws of war. However, the German Luftwaffe’s bombing of Guernica, Spain (1937) and the Japanese bombing of Chongqing (1938) weakened this taboo, and as World War II intensified, other countries gradually began to adopt the practice. This approach to aerial bombing differs from “precision bombing,” which targets military facilities instead of residential areas. LeMay, however, eventually concluded that low-altitude mass bombing was a more desirable approach in the case of Japan, as a means of achieving maximum effectiveness while minimizing the damage to his own forces. He justified this approach to aerial bombardment by arguing: “You can’t simply fight a war without some civilian casualties.” He then proceeded to carry out just this strategy on a massive scale in the aerial attacks on the Japanese mainland during the later stages of World War II.

However, Kamioka believes we should not lay the blame solely on LeMay. After all, at the time Japan was allied with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, had invaded other countries, and had attacked American territory and forces at Pearl Harbor. Furthermore, Americans believed that “no matter how hard they were pushed, the Japanese would not surrender.” Fighting against such an enemy, “the US military and the American people as a whole believed that they were righteous and that Japan represented evil, making the practice of indiscriminate bombing both unavoidable and justifiable.”

In addition, the Army Air Forces at the time was a unit within the US Army, and senior officers had ambitions to detach the unit and create an independent military organization called the Air Force. They thus had an incentive to demonstrate the potency of air power and claim credit for ending the war through the air raids. LeMay was the “man of the hour” who would take charge and was willing to lead the bombing campaign.

A Pragmatic and Competent “Man of Action”

Following LeMay’s life, Kamioka concludes that he was “the ultimate pragmatist.”

LeMay came from a poor family. When he was a child, he happened to see an airplane in flight, touching off his yearning to become a pilot. In the military, he worked his way up the ladder based on his eager study of piloting, navigation, and aircraft maintenance methods. He gained a reputation for competence and action and was always concerned about the most efficient way to achieve results.

LeMay was awarded the First Class, Grand Cordon, of the Order of the Rising Sun by the Japanese government in 1964, the tenth anniversary of the founding of the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force.

Kamioka believes that the then Japan Defense Agency recommended the decoration for LeMay out of a “genuine desire” to “express gratitude to the head of the United States Air Force.” It was, according to Kamioka, “customary for United States military personnel who had contributed to the Self-Defense Forces to be considered for decoration when they retired—irrespective of their wartime involvement or deeds.”

The fact that LeMay, who reduced so many Japanese cities to rubble, was decorated by the emperor of Japan was only covered widely in local newspapers in Hiroshima and Okinawa. On the national level, there was surprisingly little coverage, and no protests or demonstrations were held.

Professor Kamioka Nobuo. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

Kamioka suggests that the reason for this was that “the Japanese public was not really aware that LeMay supervised the air raids on the mainland.” Furthermore, the damage caused by the atomic bombs held greater prominence in postwar Japan than the firebombing. LeMay was not deeply involved in the planning of the dropping of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, only witnessing the departure of the aircraft carrying the bombs.

Nevertheless, Kamioka believes that, “since LeMay directed numerous aerial bombing raids that took a massive number of lives, the Japanese government should have debated whether he was truly deserving of the decoration, rather than simply implementing the recommendation of the Defense Agency. This is especially the case as LeMay was a controversial figure in the United States itself at the time because of his ultrahawkish views on the use of military power. The Japanese media should also have taken greater interest in investigating and reporting on LeMay’s background and the appropriateness of the award.”

“Peace Through Strength” Thinking Prevails Even Today

LeMay gained notoriety for his belief that you cannot win modern wars without killing civilians, and is regularly quoted as saying that “all war is immoral and if you let that bother you, you are not a good soldier.” LeMay was known to espouse a “peace through strength” concept, arguing that overwhelming American military power was the best way to convince antagonists there was no way for them to win, thereby avoiding future conflicts in the first place. He showed little imagination or compassion for the defeated. According to Kamioka, this was not a problematic characteristic of LeMay himself, but rather of the American approach to war.

Kamioka believes that people can be roughly divided in two categories: “those who possess imagination and empathy for people in a different situation from them—and those who do not.” LeMay was in the latter category. He never paid attention to or mourned the hundreds of thousands of Japanese who lost their lives as a result of his orders. According to Kamioka, such people still dominate the American political and military establishment to this day, and do not hesitate to suppress dissenting views. Even after the quagmire that was the Vietnam War stimulated antiwar sentiment and opposition in the United States and globally, many still stuck with the righteousness of the “peace through strength” mentality that LeMay characterized.

Kamioka views the lessons from his research as applicable to this day.

“The American people have not been educated properly to reflect on the mistakes of their own country. . . . This is why there are so many people who simplistically believe in the righteousness of the United States, and think that peace can be achieved with only a little sacrifice of life, given the willingness to use force to suppress other countries. This ‘peace through strength’ mentality continues to gain momentum today.”

In his examination of the contemporary situation, Kamioka describes US President Donald Trump as the ultimate example of someone lacking imagination and empathy:

“Because of the United States’ significant global power and influence, I worry that the ‘America First’ notion—the idea that Americans should only think about what is good for their country right now—could result in global turmoil that ultimately brings everything tumbling down. I am a teacher of literature, and literature helps us to imagine the feelings of others and develop compassion for them. I believe that the power of literature is needed more than ever at a time when many countries are adopting similar approaches to foreign policy as the Trump administration.”

If There Was No War, What Would Have Become of LeMay?

Kamioka is a literary scholar, and so writing a book about a soldier and highly ranked military officer like LeMay might seem surprising. He reflects on how his own family’s war history and experience motivated him to take up the topic.

In Professor Kamioka’s office at Gakushūin University. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

“My father was trained as a ‘human torpedo’ at the naval submarine school in Ōtake, Hiroshima Prefecture. Fortunately, the war ended before he was sent in for action. My mother also experienced the 1945 Jōhoku Air Raid in Tokyo. My parents’ stories instilled in me an understanding of the cruelty of war and inspired me to write this book.”

Kamioka ultimately believes, though, that LeMay was not an inherently brutal or murderous man and was in fact “a superior officer trusted by his men and a husband and father who cherished his family.” LeMay was a contemporary of the French aviator and novelist Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, and both dreamed of taking to the skies at a time when aviation was just emerging out of its infancy—although one would go on to be a military man and the other the celebrated author of works including The Little Prince. Kamioka believes that LeMay would have made a fine pilot if not for the war. However, his competence and faithfulness to his duties ultimately led to the deaths of many people. Kamioka reflects on how “war creates people like LeMay . . . war makes people do atrocious things. That is why we should avoid war at all costs.”

Professor Kamioka at the Gakushūin University Campus. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

(Originally published in Japanese on September 26, 2025. Text by Koizumi Haruna and Power News’s Igarashi Kyōji. Banner photo: Kamioka Nobuo’s latest book [© Hayakawa shobō] and its subject, Curtis LeMay. [© AP/Aflo])