“Ema”: Wooden Tablets Bearing Wishes for Good Luck and Success

History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Wooden votive tablets known as ema can be seen hanging in shrines and temples across Japan. Making a wish on these simple pieces of wood decorated with a picture is a deeply rooted belief among Japanese people. They can be used to pray for many different things, such as luck in matchmaking, good health, recovery from illness, and success in business. Here we look into their background and the wishes they represent.

Origins as an Equine Offering to the Gods

Japanese people regarded horses as sacred, believing them to be a vehicle for the gods, and there was an ancient custom to offer the animals to shrines. In larger shrines, these sacred horses, known as shinme, were kept in stables and it was said that the gods rode them whenever they traveled. There are still stables in some shrines today.

Only people of high status who had the financial means to keep or buy a live horse were able to dedicate it to a shrine. This led to people dedicating horse figurines, or umagata, instead that were made out of clay, wood, or straw. An even simpler offering was a wooden tablet decorated with a picture of a horse. This is how ema came to be.

The first documented use of the word ema was in the Honchō monzui, a poetry collection written in the Heian period (794–1185). In the passage for the year 1012, there is mention of an ema depicting three horses. The custom of dedicating ema can be traced back further still, to the eighth century.

In 1972, an ema from the Nara period (710–94) was discovered at the Iba archaeological site in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture. More recently, a tablet depicting a horse, thought to be from the same period, was found during excavations in 2012 and 2013 at the Shikata archaeological site in Okayama Prefecture.

The ema from the Iba site measures approximately 9 centimeters wide and 7 centimeters long. The one from the Shikata site is approximately 23 centimeters wide and 12 centimeters long. In a way, they are the prototype for the ema often seen today.

One of the oldest ema votive tablets in Japan, excavated from the Iba archaeological site. (Courtesy Hamamatsu City History Museum)

Diversification of Ema Motifs

Ema were originally only dedicated to Shintō shrines, but from the early Muromachi period (1333–1568) they began to be dedicated to Buddhist temples too, according to the scholar Iwai Hiromi. From the mid-Muromachi period the ema illustrations started to become more diverse.

For example, there is an ema from 1436 at Shirayama Shrine in Kōka, Shiga Prefecture, which depicts the Thirty-Six Poetic Immortals and bears a written wish to be able to compose a wonderful poem like that of a great waka poet.

An ema from 1787 at Kotohiragū Shrine depicting the Rokkasen, six notable mid-ninth-century Japanese poets, including Ariwara no Narihira and Ono no Komachi. From the Kotohiragū ema kagami compilation of ema at Kotohiragū Shrine. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Another example is an ema from 1459 at Ōtokonushi Shrine in Nanao, Ishikawa Prefecture. It depicts a flower cart and women enjoying leisure time, and most likely symbolizes a sincere wish for continued fortune in war and the preservation of women’s beauty.

A wooden Buddhist decoration with the painting of a woman on horseback. Although different from the ema at Ōtokonushi Shrine, this is an early example of women appearing as a motif, from the Muromachi period. Its fan-shape is characteristic and represents the kind of elaborate designs for ema that began appearing in the fifteenth century. (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum)

Entering the Warring States period (1467–1568), new variations of motifs began to appear. This included an ema dating from 1521 that depicted Monju Bosatsu (the Bodhisattva Manjushri) to symbolize wisdom, from the Kōfukuji temple in Nara; one dated 1552 of Benkei and Minamoto no Yoshitsune, representing an oath of fealty between lord and servant and prayers for victory in war, from Itsukushima Shrine in Hiroshima; and one from around 1554 showing Udennō (Udayana), an ancient king of India who worshipped Buddha and so symbolizes devoted faith (origin unknown).

The type of wishes that people wanted to express through votive tablets changed along with the times.

A depiction of Udennō (Udayana) with a lion. It was created in around 1554. (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum)

How Ema Came to Be Sold All Year Round

The size of the ema also underwent changes, becoming larger. Special halls known as emadō were built to display the dedicated votive tablets and much larger, framed ema were created to hang above the entrances.

During the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568–1603) it was common for items to be opulent and decorative, so many large, gaudy ema were created. These were offered to shrines and temples by high-ranking samurai.

A nineteenth century emadō votive tablet hall, painted by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849). (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum)

The culture of votive tablets flourished during the Edo period (1603–1868) with the emergence of ema artisans, who specialized in painting motifs. Regarded as an integral part of folk religion, ema became more widely known and loved by the common people. In particular, ema that were made to coincide with the day in February known as hatsuuma, the first day of the horse according to the lunar calendar, sold very well and remained popular even into the Meiji era (1868–1912).

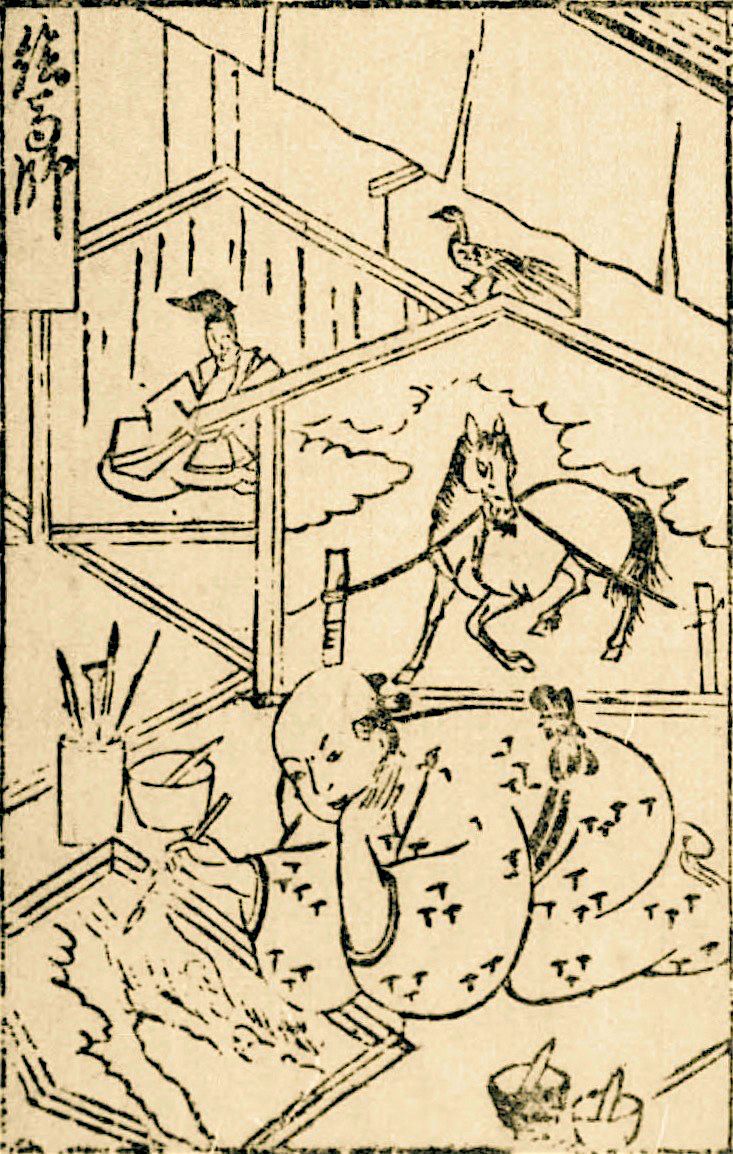

An ema artisan from the Edo period illustrated book of occupations, Jinrin kinmō zui (An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Humanity). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

A change was seen in 1892, when the Yomiuri Shimbun reported that 300 ema at Suitengū Shrine, where a god that blesses women with children and easy childbirth is enshrined, sold out in a single day. From then on, some form of ema was sold all year round.

During conflicts from the Sino-Japanese War to World War II, many ema were dedicated by people wishing for victory in battle and military fortune. In postwar times, people dedicated them to pray for luck in matchmaking and the financial fortune to be able to live a stable life. An increasing number of commercially minded temples and shrines began changing the motifs on their ema each year to match the eto or Chinese zodiac animal for the New Year period, when people would conduct hatsumōde, the first visit of the year to a place of worship.

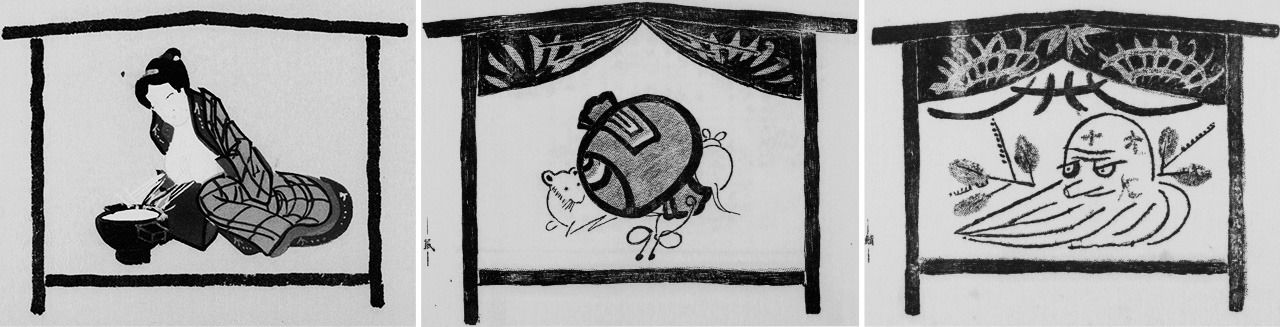

From the Meiji era, compilation booklets containing photographs of new types of ema began being published. The motifs shown here (from left to right) are “breastfeeding” to wish for children’s growth, the “rat” signifying the first animal in the Chinese Zodiac, and an “octopus” to pray for the removal of warts and calluses. This last one is a play on the Japanese word tako, which can mean both “octopus” and “wart.” All of these ema were dedicated at Takoyakushi Jōjuin temple in Meguro, Tokyo.

Then in the 1960s, the first baby boom generation headed to high school and on to university, leading to the start of what were termed “entrance exam wars” due to the intense competition for school places. It became extremely popular to dedicate ema to Tenjin, the god of academics and learning, to wish for success in passing exams, and this has now grown into a tradition for exam season.

There are probably very few Japanese people who have never dedicated an ema. These votive tablets are a true example of the proverb komatta toki no kamidanomi (literally, “calling on the gods in times of trouble”), which expresses Japanese people’s view of religion. We should remember, however, that this small wooden tablet was once a pious offering given by the common people who wished to be of service to the gods, but did not have the means to dedicate a sacred horse.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: Ema offered to Yushima Tenjin Shrine in Bunkyō, Tokyo. © Pixta.)