Interpreting the Meiji Constitution: Democracy and Militarism

History Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Greeted with Elation

The Meiji Constitution was drawn up in the Prusso-German style, centered on imperial power. The emperor could make decisions on war and peace and the members of the government, and commanded both the army and navy. The document’s first article states that “The Empire of Japan shall be reigned over and governed by a line of Emperors unbroken for ages eternal,” while the third says that “The Emperor is sacred and inviolable.”

Emperor Meiji maintained considerable power in the constitution. (© Jiji)

The news that Japan’s first constitution would be promulgated on February 11, 1889, was greeted with elation by the populace.

The streets of Tokyo filled with festival floats, and were festooned with national flags, lanterns, and flowers, as people gathered, crying out, “Banzai!” Many stores sold out of flags, and there was a roaring trade in lanterns, with artisans working through the night to produce new stock. Even rising prices did not deter the eager buyers. Restaurants and geisha houses also did good business.

Erwin von Bälz, a German doctor and adviser to the Japanese government, observed in a diary entry that “People are making a great noise, but it’s a ridiculous fact that nobody knows what will actually be in the constitution.”

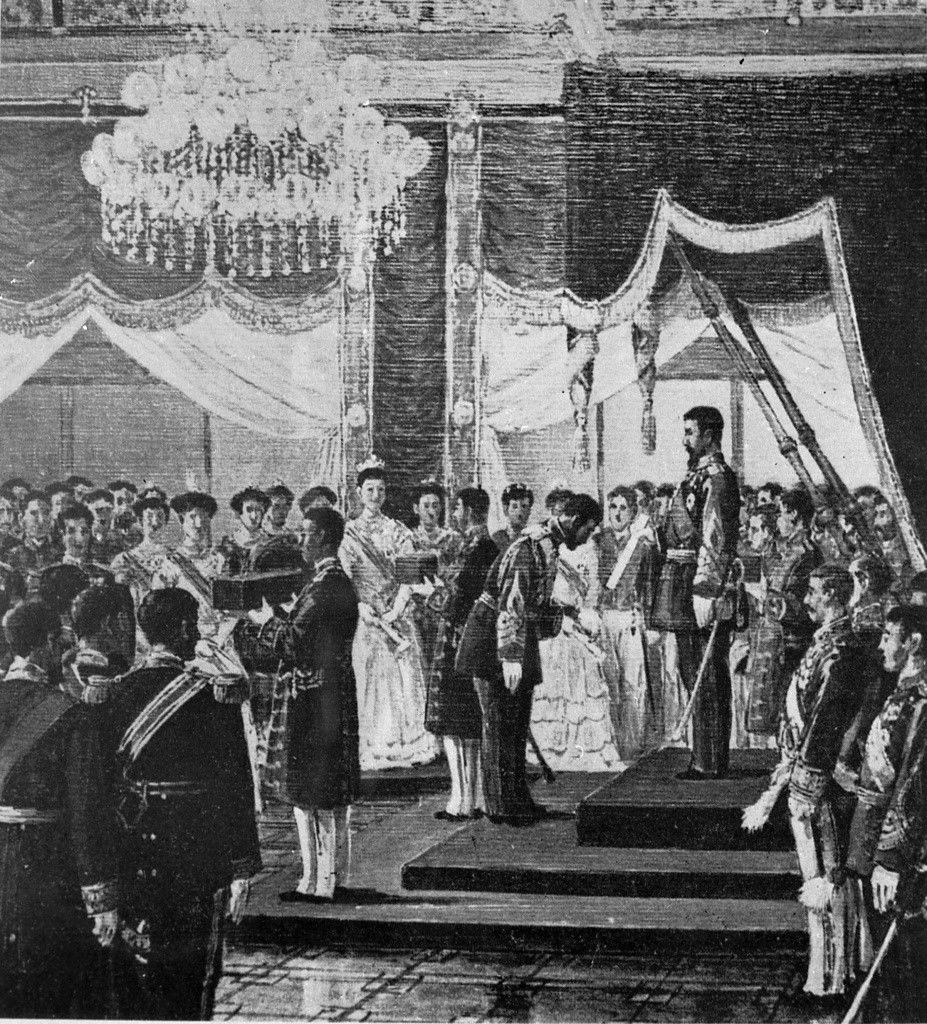

An image of the ceremony for promulgating the Meiji Constitution on February 11, 1889. (© Kyōdō)

Power to the Cabinet

Alongside the reaction from ordinary citizens, there were unexpectedly few complaints from the popular rights activists who had lambasted the government for not granting individual freedoms. This was probably because the constitution was more democratic than they had been expecting.

While it was built around strong imperial power, the constitution gave citizens freedom of religious belief, speech, and publication, and the liberty to hold meetings, form associations, and live where they pleased, within the boundaries of the law. They also had the right to secrecy in their correspondence and to private property.

The judiciary was made independent of the executive, for a clear separation of the three branches of government, and the Imperial Diet was established, holding the power to consider draft laws and budgets. The House of Representatives, consisting of elected members, could propose laws and had the first chance to discuss budgets. This opened the way to popular political participation.

Itō Hirobumi, who was central to the drawing up of the Constitution, is thought to have been highly influential in these areas.

Itō moved to concentrate executive power in the cabinet, curbing the authority of the emperor. He stated in the Privy Council during discussions on the nature of the Constitution: “In a constitutional political system, it is important to limit sovereign power and protect citizens’ rights.” It is likely that he perceived Japan’s need in the near future for party politics based on parliamentary democracy. Itō himself established the political party Rikken Seiyūkai (Friends of Constitutional Government) in 1900, and was its president during his fourth term as prime minister.

Thus, while the Meiji Constitution has sometimes been seen as undemocratic, based on an affirmation of dictatorial imperial powers, this was not the case. It could also be interpreted as a highly democratic document. Itō surely recognized this quality.

The Emperor as Organ of the State

A democratic view of the Meiji Constitution is apparent in the tennō kikan setsu or theory of the emperor as an organ of the state, advocated in the early twentieth century by Professor Minobe Tatsukichi of Tokyo Imperial University. This viewed the state as a legal person holding sovereignty, and the emperor as its supreme organ, acting under the Constitution.

In other words, Minobe saw the state as an assembly of many people with the same goals. As the emperor, Diet members, and ordinary citizens were a group connected by these shared goals, the emperor as the supreme organ of the state should conduct politics for the group as a whole.

Consequently, Minobe was opposed to an autocracy in which the emperor suppressed the rights of citizens and demanded complete obedience of them, arguing instead in favor of party cabinets.

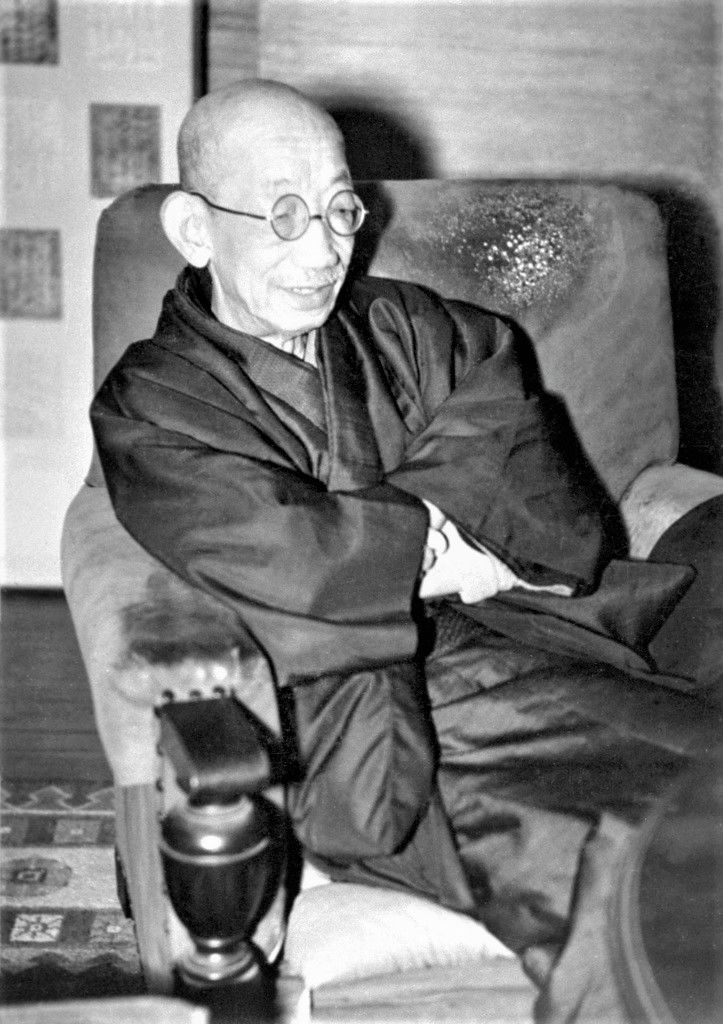

Minobe Tatsukichi discusses the Constitution in his own home after the end of World War II on January 23, 1946. (© Kyōdō)

The legal scholar Uesugi Shinkichi, also of Tokyo Imperial University, took issue with Minobe’s interpretation, insisting in his turn on the absolute power of the emperor.

However, the tennō kikan setsu became mainstream, providing the theoretical basis for the party cabinet system, and greatly contributing to its continuation through the 1920s and into the early 1930s.

A Row Over Disarmament

In 1930, there was a political storm over the emperor’s command of the armed forces, as written in the Constitution.

From January, Britain held a conference of the world’s major naval powers in London, with the aim of limiting the accumulation of naval armaments. In April, Japan, the United States, Britain, France, and Italy signed a treaty limiting tonnages of auxiliary ships (cruisers, destroyers, and submarines).

At this time, the overall ratio of auxiliary ships for Japan was set at 69.75% of that of the United States and Britain. This was higher than the 60% ratio set for battleships and aircraft carriers in the 1922 Washington treaty, and almost at the targeted 70% level. Even so, Japan was forced to compromise with a 60% ratio for heavy cruisers.

Cruisers are between battleships and destroyers in size, and are faster than the former, and stronger in battle and more seaworthy than the latter. Heavy cruisers can be a match for battleships, so there were voices of discontent within the Japanese navy, but the government still went ahead and signed the treaty. Japan was represented in London by former Prime Minister Wakatsuki Reijirō and Navy Minister Takarabe Takeshi.

The navy itself was divided into two factions over whether Japan should sign. The Naval General Staff Office was at the forefront of opposition. This was a body under direct control of the emperor, which oversaw naval strategy and tactics in wartime.

Sensing an opportunity to topple the government, the opposition Rikken Seiyūkai and conservative Privy Council joined the treaty opponents. Right-wing citizens also expressed their agreement. Together, these groups attacked Prime Minister Hamaguchi Osachi’s cabinet as infringing the authority of the emperor.

Article 11 of the Constitution stated that, “The Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and Navy.” However, the cabinet had the role of counseling the emperor when deciding the size of these forces.

That is to say, in wartime, the cabinet could not give orders to the military; instead the general staff offices of the army and navy conducted strategy with the approval of the emperor. Meanwhile, the cabinet could effectively decide the size of the military forces. In this sense, there was no problem with signing the London treaty.

Complicating matters, however, the Naval General Staff Office regulations stated that its consent was required for decisions on the size of the navy. Treaty opponents used this to denounce Hamaguchi’s government for violating imperial authority by signing without the agreement of the office.

Rising Political Violence

However, Prime Minister Hamaguchi did not give way in the face of these attacks, setting himself firmly in opposition to those who criticized the treaty, and giving top priority to cooperation with the United States and Britain.

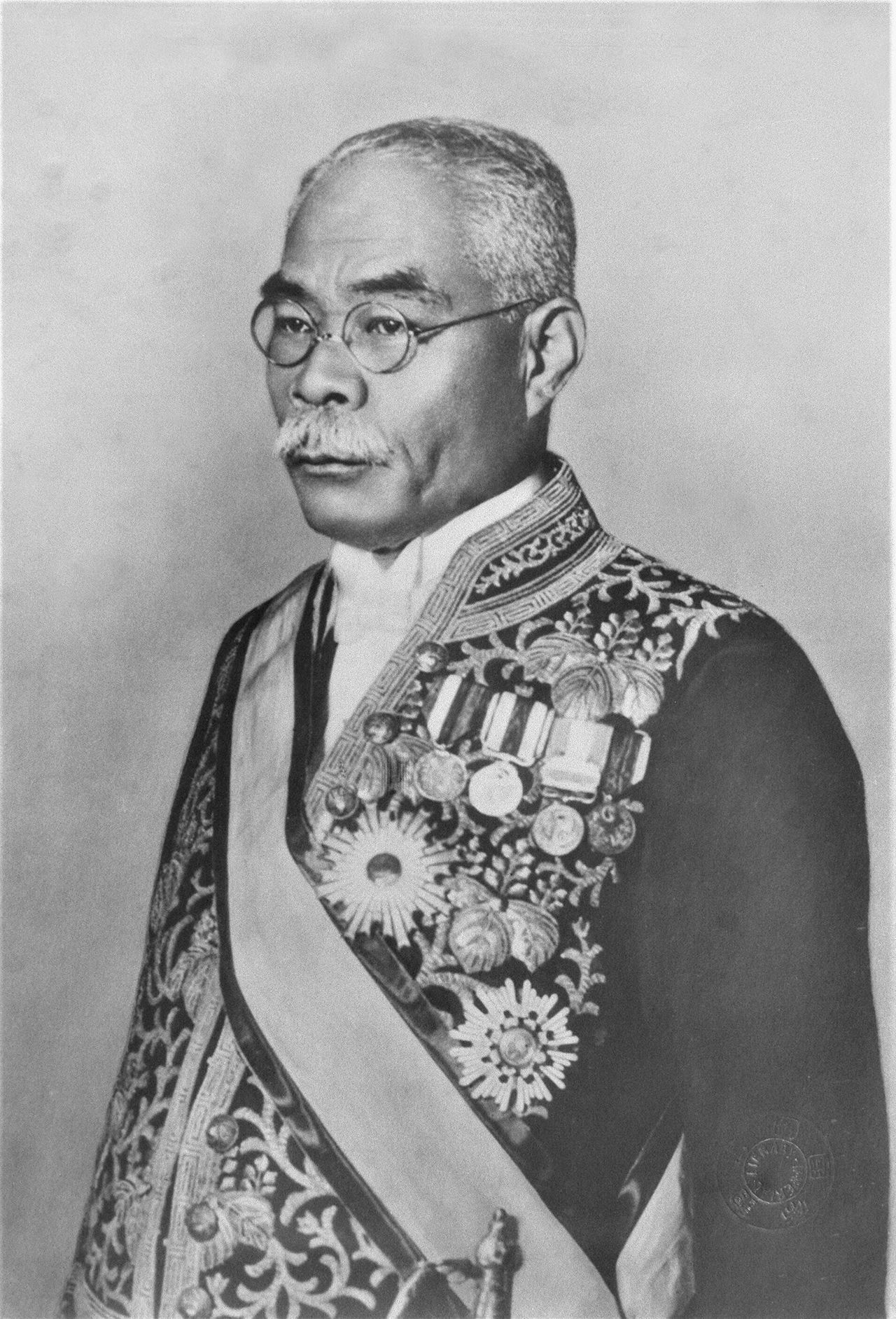

Hamaguchi Osachi’s appearance led to his nickname as the “lion prime minister.” (© Jiji)

Hamaguchi’s ruling Rikken Minseitō (Constitutional Democratic Party) had won a landslide in the February 1930 election, and an overall majority allowed him to take a stand. The media and public opinion also supported disarmament and backed the government.

With these favorable conditions, Hamaguchi deployed Minobe’s tennō kikan setsu among other arguments to subdue his opponents, and threatened to dismiss the chairman and vice-chairman of the Privy Council. However, on November 14, 1930, Hamaguchi was shot and seriously wounded by a right-wing gunman at Tokyo Station, eventually dying of his injuries the following August.

A plaque marks the spot where Prime Minister Hamaguchi Osachi was shot at Tokyo Station. (© Jiji)

Then the Manchurian Incident in September 1931 led to a switch in public support to the military. The rapid rise of militarism, and the assassination of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi in May 1932 by young naval officers, brought down the curtain on the era of party politics.

Antidemocratic Interpretations Become Mainstream

In this nationalistic climate, Minobe Tatsukichi’s tennō kikan setsu came under fire in 1935. Kikuchi Takeo, a member of the House of Peers with a military background, blasted it as unpatriotic, and other right-wingers followed suit.

Minobe was by then professor emeritus at Tokyo Imperial University, and also a member of the House of Peers, but a campaign denouncing his theory demanded that he give up his position in the house, that his works should be banned, and that academics and bureaucrats supporting the theory should be dismissed from their posts.

The government of the time, headed by Prime Minister Okada Keisuke, initially expressed approval of the tennō kikan setsu, but buckled under pressure when it became the focus of criticism. Minobe’s books were banned, and he was forced to resign.

Okada also issued a declaration renouncing Minobe’s theory as contrary to the imperial system and affirming the sovereign power of the emperor.

From this point, the constitutional interpretation that the emperor had supreme power became mainstream, with readings that further encouraged the growth of militarism.

In 1936, factional strife heightened in the army between radicals who called for direct action in the name of the emperor and others who were more moderate. In what became known as the February 26 Incident, radical junior officers led 1,400 soldiers to seize Nagatachō and Kasumigaseki, the government and bureaucratic centers in the middle of Tokyo. They broke into the prime minister’s official residence, homes of ministers, and the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, killing Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Saitō Makoto and Finance Minister Takahashi Korekiyo—both former prime ministers—and Inspector General of Military Education Watanabe Jōtarō, among others.

The Sannō Hotel in Minato, Tokyo, which closed for business on October 5, 1983. Established in 1932, it became the headquarters from which radicals plotted a coup in the February 26 Incident of 1936. In the postwar era, it was used as a US military facility. (© Jiji)

Kita Ikki, a writer from Sado, Niigata Prefecture, who posited that the emperor was above the Constitution, had a great influence on the radical group. In Nihon kaizō hōan taikō (An Outline Plan for the Reorganization of Japan), Kita wrote that the emperor should use his authority to suspend the Constitution, declare martial law, and reform the nation.

Japan followed the road of militarism into war with China, and later the United States, ending in defeat. After the end of World War II, in October 1945, the occupying General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers ordered Prime Minister Shidehara Kijūrō to fundamentally revise the Constitution to make it more democratic. Japan’s current Constitution came into effect on May 3, 1947, replacing its Meiji predecessor.

(Originally published in Japanese on March 2, 2023. Banner photo: People celebrate the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution. A contemporary news report described scenes in Kyoto as similar to the Gion Festival. Exact date and location of the photograph unknown. Taken by Suzuki Shin’ichi. Courtesy Nagasaki University Library; © Kyōdō.)