Ikkyū Sōjun: The Enduring Legacy of a Zen Renegade

Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Among the most famous and best-loved figures in Japanese Buddhism is Ikkyū Sōjun (1394–1481). A devout but eccentric monk of the Rinzai school of Zen, Ikkyū attracted a large number of followers in his day, but his wider popularity dates to the Edo period (1603–1868), when anecdotes illustrating his quick wit and ingenuity spread through all levels of society.

More recently, Ikkyū’s position in popular culture was cemented by the animated TV series Ikkyū-san (produced by Tōei Animation), based on the abovementioned stories. The program’s 296 episodes, which originally aired between 1975 and 1982, portray Ikkyū as a cute and clever young acolyte who uses his wit to solve problems large and small, outsmarting even the shōgun. The creators of the anime skillfully incorporated trademark gestures along with well-known aspects of Zen culture. Ikkyū’s Zen meditation is accompanied by the sound of a wooden temple block (mokugyo, or wooden fish), while the chime of a meditation bell announces his flash of insight. The scenes in which he pines for his mother, from whom he had been separated, add a compellingly sentimental touch.

Repeats of Ikkyū-san continued to be aired for years, and the fan base expanded intergenerationally. The series was also broadcast in China, where it was such a hit that schoolchildren vied with one another to memorize the program’s Japanese theme song. Ikkyū-san also attracted a big following in Thailand and even in Iran. The popular image of the Ikkyū that prevails in Japan and elsewhere today owes much to this animated series.

Not surprisingly, however, the adorable young scamp portrayed in the TV series has little in common with the historical Ikkyū. A complete biography of Ikkyū, who lived to be 88 (an astonishing feat of longevity for that period in history), is far beyond the scope of this article. However, with the help of a few select episodes, I hope to sketch a more authentic picture of this influential figure than that found in pop culture.

A bronze statue of Ikkyū as a boy at Buddhist temple Shūon’an in Kyoto. (© Pixta)

A Child of Conflict

Ikkyū, as he was later known, was born in 1394 in Kyoto to a low-ranking noblewoman of the Southern Court. This was just two years after the unification of the Northern and Southern imperial courts under the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu. The boy, named Sengikumaru, is believed to have been the illegitimate son of Emperor Go-Komatsu. Yoshimitsu, who favored the Northern line, feared that the child could be used as a political weapon. For this reason, he was separated from his mother at the age of six and sent to the Rinzai Zen temple Ankokuji, where he trained to become a priest. (The TV series focuses on this period in his life.)

Ikkyū was a brilliant student, excelling particularly in the composition of Chinese poetry. At the same time, he was a stickler for spiritual rigor. It is written that he clapped his hands over his ears and left the room in anger when he heard other monks bragging about their family lineage.

At the age of 17, Ikkyū entered the temple Saikonji and studied under the Zen master Ken’ō Sōi, from whom he received the name Sōjun. At Saikonji, Ikkyū practiced a non-mainstream form of Zen that renounced all material wealth and comforts, and he became all the more rigorous in his austerity. When Ken’ō died, Ikkyū—then aged 21—was so bereft that he tried to drown himself in Lake Biwa, but one of his mother’s servants managed to stop him.

Ikkyū moved on to Shōzuian in the small town of Katata, where he became a disciple of the priest Kasō Sōdon. It was Kasō who gave him the name Ikkyū.

One day, Ikkyū was meditating in a boat on Lake Biwa, caressed by a gentle breeze, when he heard the call of a crow and achieved enlightenment. Ikkyū’s master Kasō wanted to grant him the inka, a much-prized document recognizing the recipient as enlightened and qualified to transmit the Dharma. But Ikkyū, who detested such formalities, refused. Continuing his training, he distinguished himself by his eccentricity as well as his devotion to Kasō, who chose him as his heir. When Kasō was bedridden, the other disciples used bamboo implements to clean away his waste, but Ikkyū used his bare hands. After Kasō died, Ikkyū abandoned the temple in Katata for the life of an itinerant monk, wandering the countryside.

Ikkyū and the Merchants of Sakai

One place to which Ikkyū returned again and again was Sakai, a seaport in what is now Osaka Prefecture. At that time, when natural disasters and feudal warfare had thrown much of the land into turmoil, Sakai prospered as a major center of domestic and foreign trade. With its upstart merchant class and international influences, it was a city of progressive ideas as well as material affluence. In Sakai, Ikkyū quickly attracted attention by swaggering through the town’s bustling streets in his monk’s robes, carrying a long, red sword—an utterly bizarre and incongruous sight. When asked what he meant by such behavior, he replied, “This is a wooden sword; it cannot cut. The priests that run rampant in this world are like my wooden sword here—handsome fakes that are utterly useless in a crunch.” Ikkyū directed his criticism not only at the priests themselves but also at the townspeople who bought into their fakery. His message was that such behavior was no more rational than his.

A portrait of Ikkyū with his famous red sword. (Courtesy of Shūon’an)

Among those drawn to Sakai (then Japan’s most prosperous town) was another, more senior, disciple of Kasō, named Yōsō Sōi. Leveraging his inka, Yōsō was working to broaden Zen’s sphere of influence from the warrior elite to the merchant class. To do so, however, he felt obliged to “dumb down” Rinzai teachings, since the typical merchant had neither the education nor inclination to pore over Chinese texts. Ikkyū, with his deep erudition and spartan rigor, found this approach intolerable. As far as he was concerned, Yōsō—notwithstanding his position as Ikkyū’s elder and one of Kasō’s chosen heirs—was just another “wooden sword.”

Ikkyū’s own very different approach—a combination of rigor and iconoclastic eccentricity —exerted an appeal all its own among the free-thinking citizens of Sakai (who were doubtless impressed by his imperial blood as well). Many of the town’s wealthy merchants studied and trained under Ikkyū. Recent research has shed light on this interesting and diverse group of followers, including one who traveled to China by stowing away on a trading vessel and another, of mixed Chinese and Japanese parentage, who became an interpreter.

Life and Legacy of an Iconoclast

Ikkyū’s iconoclasm was legendary. He disdained titles and badges of honor. In his view, the much-sought-after inka, which “certified” a monk as enlightened, was not merely useless but harmful. At the age of 47, he agreed to take over as abbot of Nyoian subtemple at Daitokuji—the head temple of the Daitokuji sect of Rinzai Zen—but he left after a short time, saying that the job of a “distinguished priest” did not agree with him. It was, perhaps, the ultimate gesture of rebellion against the religious establishment.

However, Ikkyū returned to Daitokuji late in life, after much of the temple had been reduced to ashes in the Ōnin War (1467–77). At the advanced age of 85, he accepted the position of abbot in order to aid in Daitokuji’s reconstruction out of consideration for its significance to colleagues whom he respected. He was able to enlist the support of many wealthy Sakai merchants in this costly project.

Despite his contempt for worldly honors, Ikkyū became the center of a major subsect with numerous followers. However, true to his principles, he refused to bestow the inka on any of his disciples. In 1478, his failure to anoint a successor triggered an internal crisis. The members of Ikkyū’s subsect saw their leader as the legitimate Dharma heir in an unbroken line of transmission extending all the way back to the Chinese monk Xutang Zhiyu (1185– 1269). Now the sect was facing dissolution. Ikkyū’s disciples urged him to choose a legitimate successor. There were any number of qualified candidates, but Ikkyū refused to designate one. The pressure mounted, and finally, one day, he uttered the name of Motsurin Jōtō. But when the choice was joyfully conveyed to Motsurin, he balked, insisting that the master would never have said such a thing had he been in full possession of his faculties. “How could you be so foolish after watching and listening to him all these years?” he exclaimed, and left the room in a huff.

How, then, was Ikkyū’s Dharma transmitted to later generations?

After Ikkyū’s death in 1481, his disciples decided to gather once a year at his mausoleum in Kyōtanabe to confer and decide on issues of importance to the sect. These assemblies, referred to as kesshū, closely resemble the councils held after the death of Gautama Buddha, through which the Buddha’s teachings were preserved and passed on and the early schools of Buddhism took shape. Much like the quick-witted Ikkyū of legend, his disciples arrived at an ingenious solution for preserving his legacy without the use of the despised inka. In this way, the Dharma of Ikkyū lives on today.

A wooden statue of Ikkyū at Shūon’an.

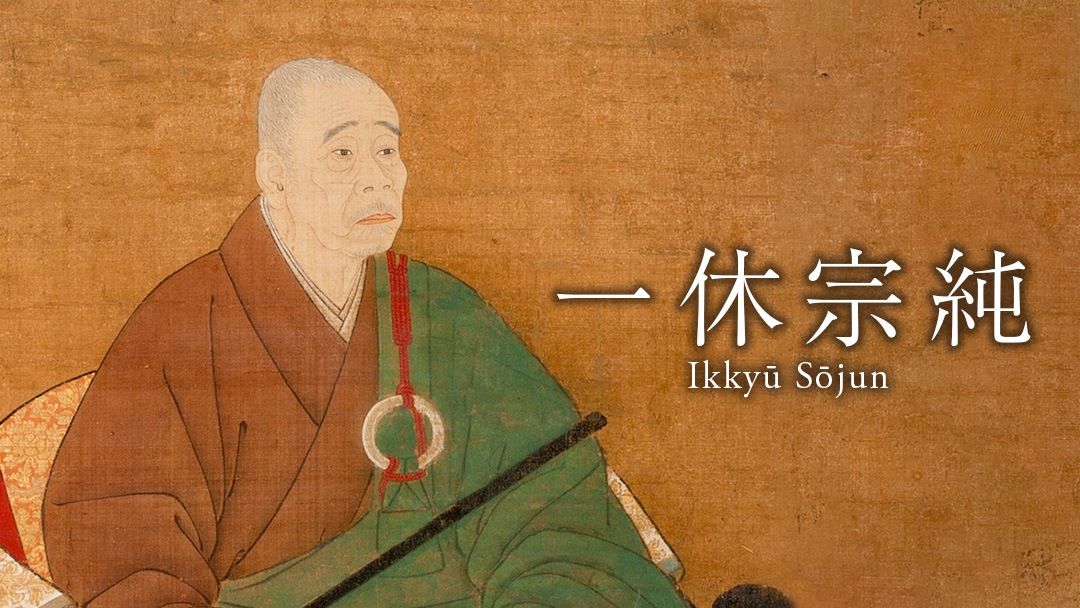

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A portrait of Ikkyū Sōjun at Shūon’an, Kyoto. Image courtesy of Shūon’an.)