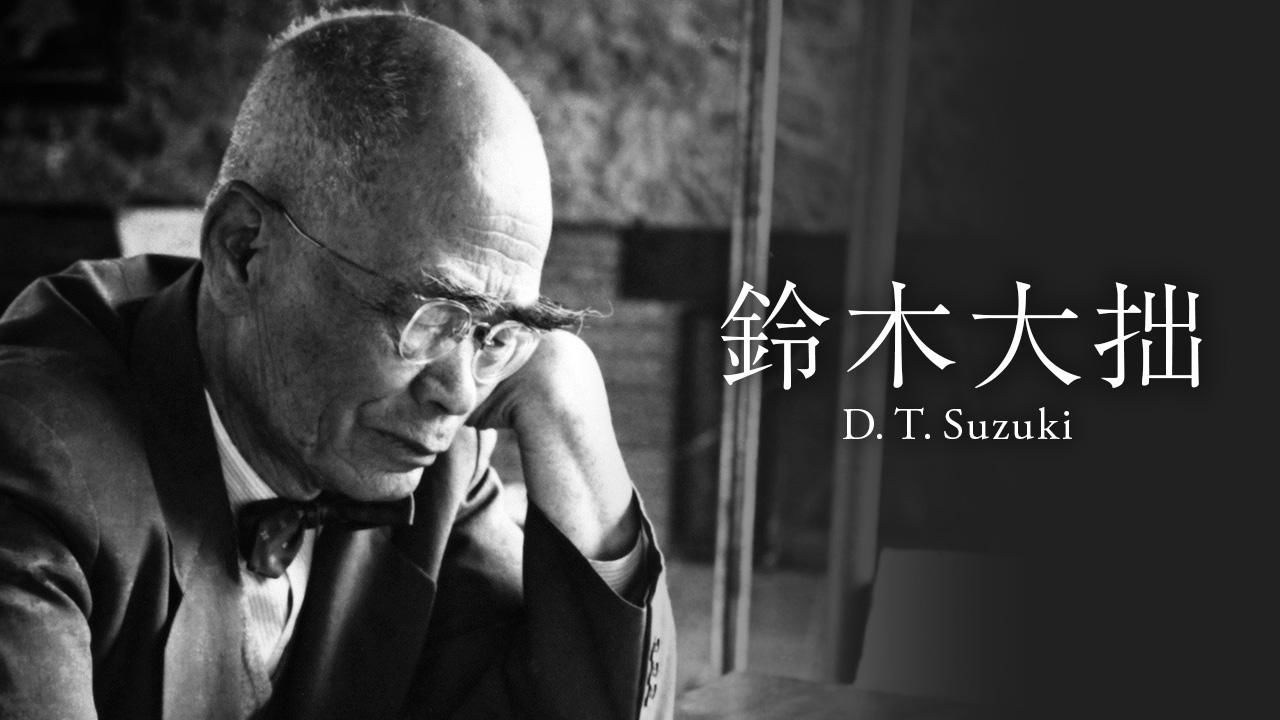

The Translation of Zen: A Tribute to D. T. Suzuki

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Suzuki Teitarō Daisetsu (1870–1966), who adopted the spelling Daisetz for his Buddhist name and was known to many in the West as D. T. Suzuki, was a scholar and author who introduced several generations of Westerners to Zen Buddhism and, more broadly, to Asian thought and Japanese culture.

The scope of Suzuki’s writing and teaching was by no means limited to the subject of Zen. For example, his groundbreaking study of the myōkōnin, ecstatic lay followers of the Jōdo Shinshū sect of Buddhism, figured prominently in his 1944 book Nihonteki reisei (Japanese Spirituality), and his translation of Kyōgyō shinshō by the sect’s founder, Shinran, was an important addition to the body of English-language Buddhist literature. Nonetheless, Suzuki is best known for the role he played in transmitting Zen thought to the West. Many of his Western followers referred to him as rōshi, or Zen master, though he made no such claim. In fact, it was not his original intent to win Western converts to Zen, or, for that matter, to explicate its doctrine from a theoretical or philosophical standpoint. What motivated him, rather, was the desire to share with others the wisdom he had gained from his own practice of Zen, in accordance with the Buddhist vow to save, or liberate, all sentient beings (shujō muhen seigando).

A Daunting Challenge

The saying furyū monji—no reliance on words—sums up the importance that Zen places on direct, personal experience, as opposed to the verbal transmission of religious doctrine. By nature, Zen tends to defy verbalization, and explaining it in English is all the more challenging. But if Suzuki hoped to awaken the spirit of Zen in others, he had no choice but to begin by communicating with them verbally, in their own language. The philosopher Nishitani Keiji (1900–90)—a disciple of the philosopher Nishida Kitarō, one of Suzuki’s closest friends—described his task as follows: “Suzuki’s work centered on the transmission of Buddhism, Zen in particular, and this is no simple task, even for someone conversant in Zen and foreign languages. Obviously, one needs to be fully immersed in Zen’s long tradition. But at the same time, one must be able to view it through contemporary eyes and reframe it as something relevant to today’s world.” In short, Suzuki’s task went far beyond the translation of texts or the compilation of glossaries.

Suzuki communicated his message not only through books and lectures but also through direct, off-the-cuff, personal interaction, encouraging and answering questions wherever he went. It was in such settings, edifying others through his immediate presence as well as his words, that Suzuki came into his own. He was the first person to offer open access to the experience of Zen.

Formative Years

Suzuki Teitarō was born on November 11, 1870 (the third year of the Meiji era), in the city of Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture. He came from a line of samurai physicians who had served the powerful Honda clan before the Meiji Restoration. Teitarō was still a child when his father died, and he endured much economic hardship as he pursued his academic studies.

While still a young student in Ishikawa, Suzuki made the acquaintance of a number of figures with whom he was to stay in touch throughout his life, including the philosopher Nishida Kitarō (1870–1945) and Fujioka Sakutarō (1870–1910), a scholar of Japanese classical literature. The relationship between Suzuki and Nishida was to prove particularly fruitful. Encouraging and respecting each other, and enlightening one another from their respective standpoints, they would become two of Japan’s leading thinkers, far exceeding the realms of their scholarship alone.

Suzuki’s early career was a series of struggles and reversals. In 1888, determined to attend university, he gained admittance to the Fourth Higher Middle School in Kanazawa (one of seven elite public preparatory schools recently established by the Meiji government), but economic circumstances forced him to drop out the following year and take a job as an elementary schoolteacher. That lasted only until 1889, when he made his way to Tokyo to continue his studies. Suzuki first matriculated at the private Tokyo Senmon Gakkō (predecessor of the prestigious Waseda University), and then switched to the philosophy department of Tokyo Imperial University, but he never completed his degree.

Zen at Engakuji

The most likely reason is that his priorities were changing. In 1891, Suzuki began practicing Zen at the temple Engakuji in Kamakura, not far from Tokyo. From the start he had hoped to practice Zen while pursuing his studies, but his encounter with Master Imakita Kōsen (1816–92), the abbot of Engakuji, inspired him to immerse himself whole-heartedly.

Later in his career, Suzuki would often recall his first conversation with Kōsen. When the abbot had asked Suzuki where he was born, Suzuki had replied that he came from Kanazawa, whereupon Kōsen had commented, “People from the Hokuriku region have tenacity.” On its face, it seems an unremarkable exchange, but from the frequency with which Suzuki repeated Kōsen’s remark, it seems clear that he invested it with considerable significance. At the time, it must have sounded less like a sweeping generalization than a personal admonition or prophecy.

As it turned out, Suzuki never did graduate from an institution of higher education. After his meeting with Kōsen, his spiritual journey took priority.

Suzuki was bereft when Kōsen died unexpectedly in 1892, but he continued his practice under the abbot’s disciple and successor, Shaku Sōen (1860–1919). Sōen, a one-time Keiō University student who had also pursued language studies and Buddhist training in Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), later became the first priest to use the name Zen in describing this branch of Buddhism to a global audience. Sōen’s impact on Suzuki’s career was profound and enduring. It was Sōen who gave Suzuki the Buddhist name Daisetz (in 1894), and it was he who arranged for Suzuki to go abroad.

English Immersion

In 1897, at the age of 27, Suzuki traveled to the United States for the first time. At Sōen’s introduction, he assisted the religious scholar Paul Carus (1852–1919) and worked as an editor at the Open Court publishing company in Illinois. It was not an easy life, but over the course of 11 years, Suzuki acquired an international perspective and remarkable fluency in the English language.

Returning to Japan in 1909, Suzuki made a living teaching English at Gakushūin School (present-day Gakushūin University) and Tokyo Imperial University. The following year, he was granted a professorship at Gakushūin, and in 1911 he married Beatrice Erskine Lane, whom he had met overseas. The affection and respect he earned as a teacher is suggested by the number of Gakushūin students who were later to become his close associates and supporters.

Prominent among these was Yanagi Muneyoshi (1889–1961), better known as Sōetsu, who studied English with Suzuki before going on to pioneer the mingei (folk craft) movement in Japan. Linked by common beliefs and aims, as well as their early teacher-student bond, they renewed their relationship in the mid-1940s and maintained close personal and intellectual ties.

Working in tandem, the two threw themselves into the study of Zen, as well as the Pure Land Schools and the myōkōnin, with a pervading focus on the idea of mushin, the state of “no-mind.” Through Yanagi, Suzuki came into contact with key figures in the mingei movement, including the Japanese ceramic artist Hamada Shōji (1894–1978) and the English artist Bernard Leach (1887–1979). Suzuki trusted Yanagi implicitly and viewed him as the person best qualified to succeed him as head of the Matsugaoka Bunko (the Buddhist library Suzuki established in 1946). To Suzuki’s boundless grief, Yanagi predeceased him by five years.

A Permanent Base of Operations

In 1921, at the recommendation of Nishida Kitarō and the urging of Buddhist scholar Sasaki Gesshō (1875–1926), Suzuki left Gakushūin to accept a professorship at Ōtani University, a Shin Buddhist institution in Kyoto. The same year, Suzuki founded the Eastern Buddhist Society and, with the cooperation of his wife Beatrice, Sasaki, and others, launched the Eastern Buddhist, Japan’s first English-language journal on Buddhism and Buddhist studies.

With Ōtani University and the Eastern Buddhist Society as his bases of operations, Suzuki went on to publish a succession of groundbreaking works in both English and Japanese, beginning with his Essays in Zen Buddhism (1927). In 1936, he traveled abroad to lecture at Harvard, Cambridge, and other universities. Suzuki was to remain a member of the Ōtani University faculty until 1960.

Suzuki’s efforts to reach a wider audience benefitted from the support of a number of wealthy Japanese industrialists. The most important of these patrons was undoubtedly Ataka Yakichi (1873–1949). A fellow native of Kanazawa, Ataka came to Suzuki’s aid long before the latter had made a name for himself. Ataka donated the Kyoto residence where Suzuki lived with Beatrice during his years at Ōtani University. He also financed the publication of Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture (1938; subsequently revised and reissued as Zen and Japanese Culture in 1959) and sent copies to institutions in Japan and abroad. Moreover, he remained staunchly loyal and supportive during the war years, when Suzuki’s publications in English—the forbidden “enemy tongue”—left him and his associates open to suspicion. It is doubtful that Suzuki’s subsequent achievements would have been possible without Ataka’s early support.

Globetrotting Golden Years

In 1949, four years after the war’s end, Suzuki set out for the United States at the advanced age of 79 and spent most of the next decade lecturing and teaching overseas. At Columbia University, where he taught from 1952 to 1957, cultural luminaries from the avant-garde composer John Cage (1912–92) to the novelist J. D. Salinger (1919–2010) attended his lectures. (He even makes a cameo appearance as Professor Suzuki in Salinger’s 1961 novel Franny and Zooey.) Sought out by such Beat Generation icons as Jack Kerouac (1922–69), Suzuki exerted an influence that spanned America’s diverse social and cultural landscape.

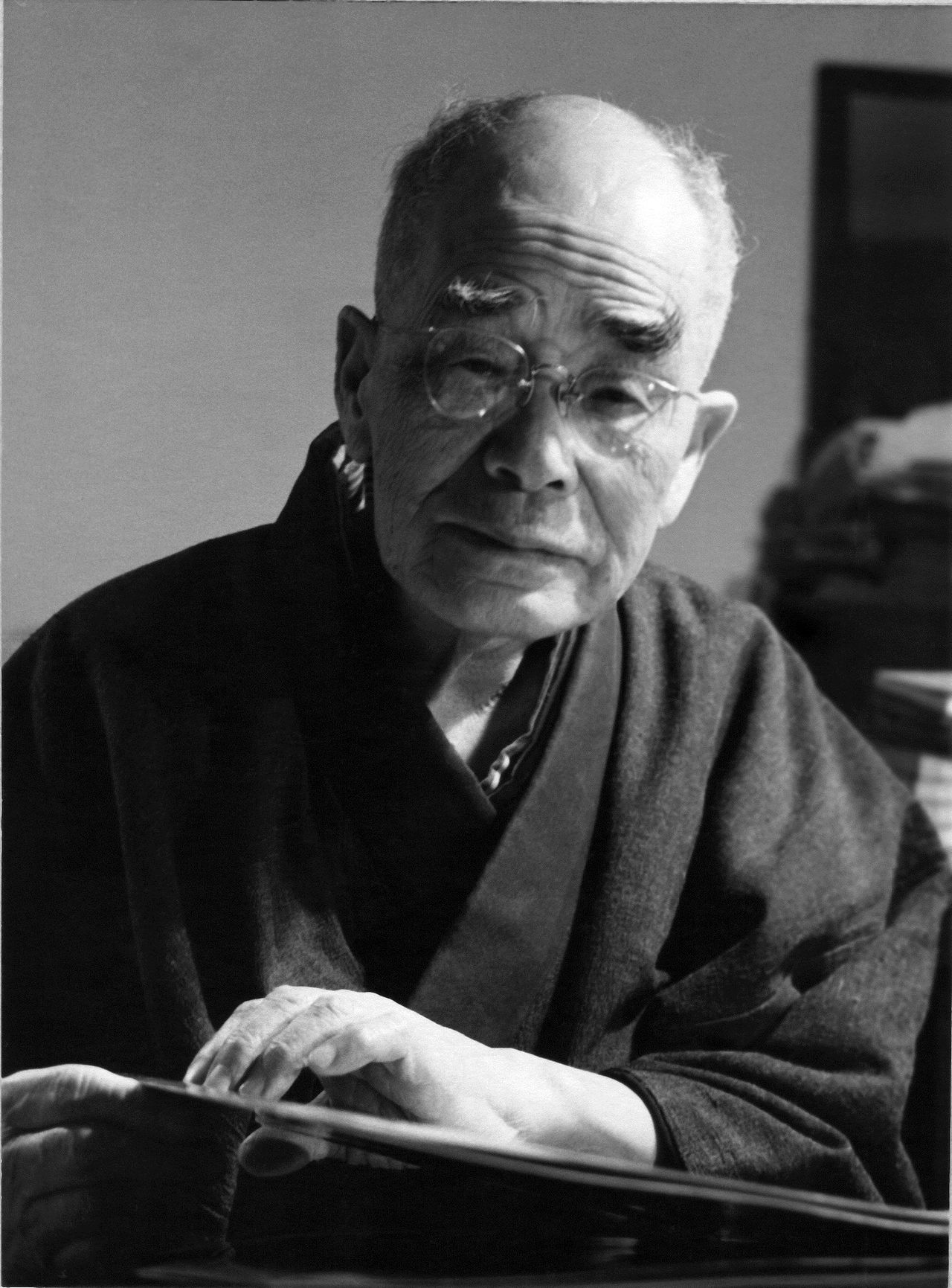

Suzuki spent the late 1950s in Kamakura, immersed in study. (© D. T. Suzuki Museum)

Suzuki described himself as a Japanese person who was also a citizen of the world.

Although he devoted his career to disseminating Eastern thought in the West, he never asserted the superiority of one culture over the other. In fact, Suzuki questioned the entire “East-West dichotomy,” just as he challenged dualistic thinking in general. As he explained it, Zen seeks a pure and immediate experience of reality, free from the distortions of such conceptual dichotomies as “good or bad,” “self or other,” and “being or nonbeing.”

This attitude informed Suzuki’s entire life, making him a potent exemplar of the wisdom he had gained from Zen and sought to pass on to others.

When Suzuki was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1963, he was identified as a Japanese Buddhist philosopher, but he himself never assumed such titles as “philosopher” or “scholar.” Okamura Mihoko, the American-born assistant who served Suzuki faithfully in his declining years, told me that he liked to describe himself as a mere schoolteacher. His ability to live life on his own terms, unfettered by social prejudices or constraints, is a revelation even today, more than 50 years after his death.

D. T. Suzuki Chronology

| 1870 | Born Suzuki Teitarō in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture, on November 11 |

|---|---|

| 1888 | Enrolls at Fourth Higher Middle School (predecessor of Kanazawa University) |

| 1892 | Enrolls at Tokyo Imperial University (predecessor of the University of Tokyo) |

| 1894 | Receives (lay) Buddhist name Daisetz |

| 1897 | (age 27) Travels to the United States, where he spends 11 years working as an editor and assistant to Paul Carus in Illinois |

| 1909 | (age 39) Returns to Japan, where he teaches English at Gakushūin and Tokyo Imperial University |

| 1911 | Marries the American Beatrice Erskine Lane |

| 1921 | (age 51) Accepts a professorship at Ōtani University in Kyoto |

| 1936 | Lectures at Cambridge, Harvard, and other Western institutions |

| 1938 | Publishes Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture |

| 1944 | Publishes Nihonteki reisei (Japanese Spirituality) |

| 1949 | (age 79) Travels to the United States; teaches at the University of Hawaii |

| 1950 | Delivers lectures at Princeton University and New York University |

| 1952 | (age 82) Begins teaching at Columbia University |

| 1954 | Embarks on a lecture tour with stops in Germany, Britain, and Switzerland |

| 1958 | (age 88) Returns to Japan |

| 1961 | Completes English translation of Shinran’s Kyōgyō shinshō |

| 1966 | Dies at the age of 95 |

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: D. T. Suzuki, age 86, at the home of Eric Fromm in Mexico, 1956. © D. T. Suzuki Museum, Kanazawa.)