Yosano Akiko and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–21

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Yosano Akiko (1878–1942), the foremost female poet of twentieth-century Japan, wrote the poem “From an Old Nest” in 1915, but it could be an ode to these past sequestered months of ours.

“From an Old Nest”

Skyward storms, don’t ask me along

while you wander aimlessly hither and yon,

bending the mountains, ravishing the fields—Earthbound as I am, I could not bear it.

Wild flowers’ fragrance, don’t murmur to me.

If I were to become a flower’s scent

I would perfume an instant of time—And then vanish forevermore.

Birds in the trees, don’t sing to me.

Born with wings, you fly

from branch to branch,singing your way from flower to flower.

All things, all, turn yourselves away from me—

Over and over in my small voice,

repeating the whisper that never changes,I rest in the nest of first love.

(Yomiuri Shimbun, July 25, 1915; Maigoromo, 1916)

The ending is a surprise—the “old” nest of the title becomes the place of “first” love. Shouldn’t it be a new nest? But that is the point. Love has survived the years. Even in the most difficult times of her marriage, Akiko believed that. And what of the unchanging whisper? Is it speaking words of love or something else? Such mysteries aside, the poem reminds us that there can be, after all, reasons to like staying at home. Sometimes there are things there that you can find nowhere else.

The romantic, visionary persona of this poem is one side of Yosano Akiko. But she was also a mother—giving birth to 13 children, 11 of whom survived to adulthood, products of a long and loving marriage—and an amazingly prolific social critic, best remembered now for the Motherhood Protection Debate (1918–19) that she carried on in the pages of widely read magazines with her sister feminists Hiratsuka Raichō, Yamakawa Kikue, and Yamada Waka. During the same period and then again a few years afterward, Akiko published five opinion pieces related to the influenza pandemic of 1918–21. Her platform was the Yokohama Bōeki Shimbun, one of the leading progressive newspapers of the day.

A Writer Takes On Pandemic

Worldwide, the influenza pandemic infected 500 million people and killed from 17 million to 50 million, possibly as many as 100 million. More than 20 million people died in World War I, so the pandemic was as deadly, or more so, than the war. In Japan, as elsewhere, exact numbers are impossible to come by, but the best estimate is that about 42% of Japanese were infected and about 400,000 died. Globally, the pandemic had three waves, the dates slightest different depending on the country. In Japan, the first wave was from August 1918 to July 1919, the second (and most virulent) from October 1919 to July 1920, and the third from August 1920 to July 1921.

In November 1918, at the peak of the first wave, Akiko published “Kanbō no toko kara” (From an Influenza Sickbed), her thoughts while she and 10 other members of her 13-person family were ill with influenza. The first half was devoted to the epidemic. Progress in global transportation, she began, made it inevitable that influenza would travel around the world, but the high degree of contagiousness of this iteration was something new. And the speed with which it could now turn from a fever to pneumonia to sudden death made it of the utmost importance for steps to be taken to contain it.

Unfortunately, she continued, the propensity of the Japanese to stick their heads in the sand instead of facing up to a problem had made a bad situation worse. “Why, “ she raged, “did not the government, early on, preventively order the temporary closing of places where many people gather in close quarters, like large dry goods stores, schools, places of entertainment, large factories, major exhibitions, and so on?” In twenty-first-century terms, she was pointing to the lack of proactive, strong leadership and the neglect of the need for social distancing and avoiding crowds. That was her first point.

Her second point was premised on the medical view that influenza, with its high fever, led to pneumonia, which led to death. Therefore, the most crucial medication was an antipyretic. Unfortunately, the best ones were too expensive for the poor, so Akiko recommended that the public and private sectors work together to supply them cheaply. In her signature fusion of classical and modern, Akiko concluded by quoting from ancient Chinese philosphers in support of her modern democratic ethos:

“Rousseau was not the first to discourse on equality. Confucius said, ‘It is not poverty I lament, but inequality.’ And Liezi said, ‘Equality is the ideal under heaven.’ In light of our new ethical awareness today, I think it is truly irrational that our fellow human beings should be deprived of the best medicine, and so endure even more suffering and anxiety, only for the material reason that they are poor.”

“Surrounded on All Sides by Death”

Akiko next discussed the pandemic in a section of “Oriori no kansō” (Thoughts and Impressions), published on February 12, 1919. By this time, the first wave had begun to wind down, but there was a slight uptick. “The global influenza has returned,” Akiko wrote, and reported that she and her husband had succumbed to it twice since last year, while the children too had caught it one after the other. What exercised her was the primitive state of urban hygiene, for example, the crowded street cars “like a box for forcibly infecting people with germs,” and their “filthy leather handstraps” that were never disinfected, not to mention the bad hygiene in schools: lack of proper heating, hand hygiene, and gargling. She deplored the Ministry of Education’s complete lack of interest in these problems, and declared that, even though she was a believer in kindergartens (a modern innovation), she was keeping her kindergarten-age son home from school.

Yosano Akiko in an undated photo. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

From mid-January the second wave was at its peak, and for a terrible three weeks the pandemic was at its height. The rate of infection was lower, but the mortality rate was much higher, and influenza was once again taking central stage in the newspapers. It was at this juncture, on January 25, 1920, that Akiko published “Shi no kyōfu” (The Fear of Death). Unlike the earlier two essays, which had been devoted to practical and medical matters, this was devoted entirely to the psychological effects of the pandemic. She began: “Seeing the ravages wreaked by the raging epidemic, how perfectly healthy people can become sick and die in five or seven days, one’s thoughts turn to the mutability of life, and to death itself. Ordinarily, we take life for granted and only think how we can live it best, but seeing this, we become like a Buddhist believer, terribly aware of the transience of life. Fear of death has come to occupy an even larger place in our awareness than the struggle for food that has consumed the lives of those who must work for a living, whether with their minds or their bodies, for the last four or five years.”

The climax of the essay is this brief passage: “Now we are surrounded on all sides by death. In Tokyo and Yokohama alone, four hundred people are dying every day. It may be our turn tomorrow, but until the very end, holding aloft the flag of Life, I want to defend myself wisely against this unnatural Death.”

She concluded by saying: “I have known the fear of death when giving birth, and also in response to today’s influenza epidemic, and it is at those times that I felt my desire to live deepen the most, not for my own individual self but for the sake of nurturing my children. When human beings become parents, they come to feel a different density, a new color, in their attachment to life. Love for the human beings that have come forth from one’s own body expands to include love for all of humanity.”

Thoughts of Mortality

In the middle of the third wave, when the number of cases and deaths were decreasing, Akiko again touched on the influenza pandemic, this time as part of her essay “Eisei to chiryō” (Hygiene and Treatment, October 1920). Evidently by this time she had come to feel it was futile to ask the government to do more than it was doing, even though in her view it was far from enough. Her remarks are all about what individuals can do for themselves and their families, and her assumption is that influenza epidemics are here to stay (as indeed it has proven to be). Thus, she begins: “The season when the terrifying ogre of influenza awakens has come around again.”

In “The Fear of Death,” she had pledged to do the best that she, on an individual level, could do to resist the sickness. In “Hygiene and Treatment,” she tells us, in effect, how she is carrying out her vow. Her methods are almost the same as those in use today. First, came good nutrition, then gargling to wash away toxins, especially after returning home from being in crowds. She recommended that employees of companies and factories should all have gargling medicine and use it often while at work. Then she reveals that she also receives periodic injections devised by her obstetrician and longtime friend, Dr. Ōmi Kōzō. In spite of the fact that the general opinion among specialists was that “vaccinations” were useless, Akiko felt the efficacy of Dr. Ōmi’s injections was proven because none of his patients and no one in Akiko’s family came down with influenza. She then gave the address of Dr. Ōmi’s clinic for those who might want to try it. Here we see the practical side of our poet, devotedly caring for the health of her family.

Akiko took up the problem of death for the second time in “Shi no kyōi” (The Dread of Death), published on February 12, 1923. At the time, there seemed to be an unusual number of death notices and obituaries in the newspapers, and a doctor she knew told her that influenza was going around. Her own children were coming down with fever and coughs one after the other. Then, her family was notified that her husband’s nephew, a young doctor studying in Berlin, had died of pneumonia on the eve of his return to Japan. Here was a young person, not yet thirty, gone in an instant. The frailty of human life came home to her and she felt her own children might even be in danger.

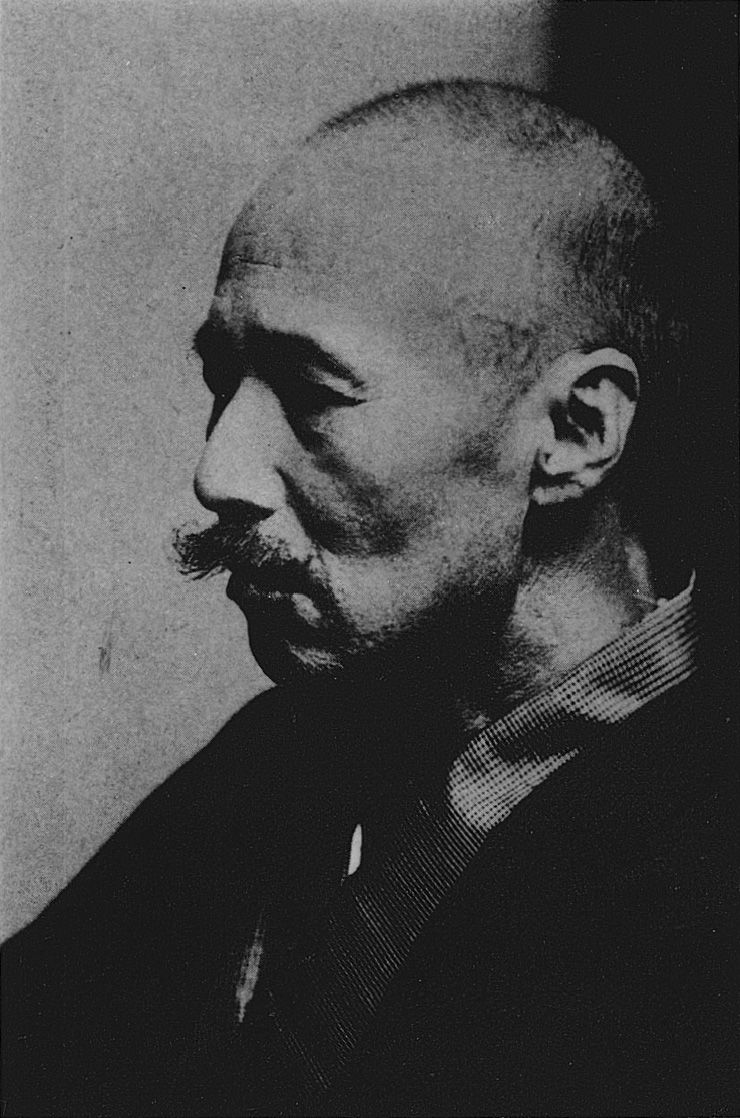

The acceptance and calm with which Mori Ōgai (1862–1922), the great novelist and her good friend, had met death the year before filled her with admiration. People like him “do not fear death like an ordinary person. When death comes they die as though returning home.” But she did not believe such equanimity was possible for her. She was one of the “ordinary people” (bonjin) who feel intense anxiety about death. She concluded by giving the same reason she had given before, in “The Fear of Death”: as a parent, “I cannot afford to die.” And so, “As the mother I am now I would fight death to my last breath with no shame whatsoever for being an unregenerate coward.”

The celebrated author Mori Ōgai, pictured here in 1916, passed away at age 60 in 1922. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Returning Reborn

And yet, there is something else here, for earlier in the essay, she talks about a general fear of death, which she ascribes to her age (she was then 45), the fact that paralytic stroke runs in her family, and the further fact that both of her parents died of cerebral hemorrhages. When she hears about the death of someone else, “I tremble as though it were a portent of my own death. My heart then seems to melt away like thin snow.” And yet, she continues, “From the depths of the heart so frightened and depressed by death, somehow a mysterious defiance and courage well up. I cannot die. No matter what, I must live.”

The rational reason, or the rationalization, may be the children: But there is this irrational and inexplicable boldness and courage, a kind of life force, that wells up in her in response to the dread of death, and whose source she does not even try to explain. In all her writings about the epidemic, this is the only mention of it, but it seems more basic to her nature than any other reason she gives.

In Akiko’s world, contagious diseases like cholera and tuberculosis were common. People died at home more often than at hospitals, so it is likely she had seen death up close, perhaps when she was nine and her paternal grandmother, who lived with her family, died. It was then that, by her own vivid account in Watakushi no oitachi (My Childhood), the child Akiko became aware of death and began to fear it. As an adolescent, she related in Aru asa (A Certain Morning), the fear of death came to obsess her, and then turned into a secret attraction. The darkness only lifted when she found poetry and love and, as she later put it, “danced out into the light.”

Yet the awareness of death lurking beneath the surface of life, sometimes a threat and sometimes an attraction, lingered on. Her pregnancies and birth were described in poetry and prose as confrontations with death from which she returned reborn. Her dread of death was definitely mitigated by the fierceness of maternal love, yet she also wrote poems during times of illness that describe a longing to give up and die, and others that describe dreams of a beautiful world beyond life. At the same time, at the moment of choice, death was always opposed by the mysterious will to live that welled up within her from she knew not where, something mysterious and bountiful. That is the Eros and Thanatos of Yosano Akiko.

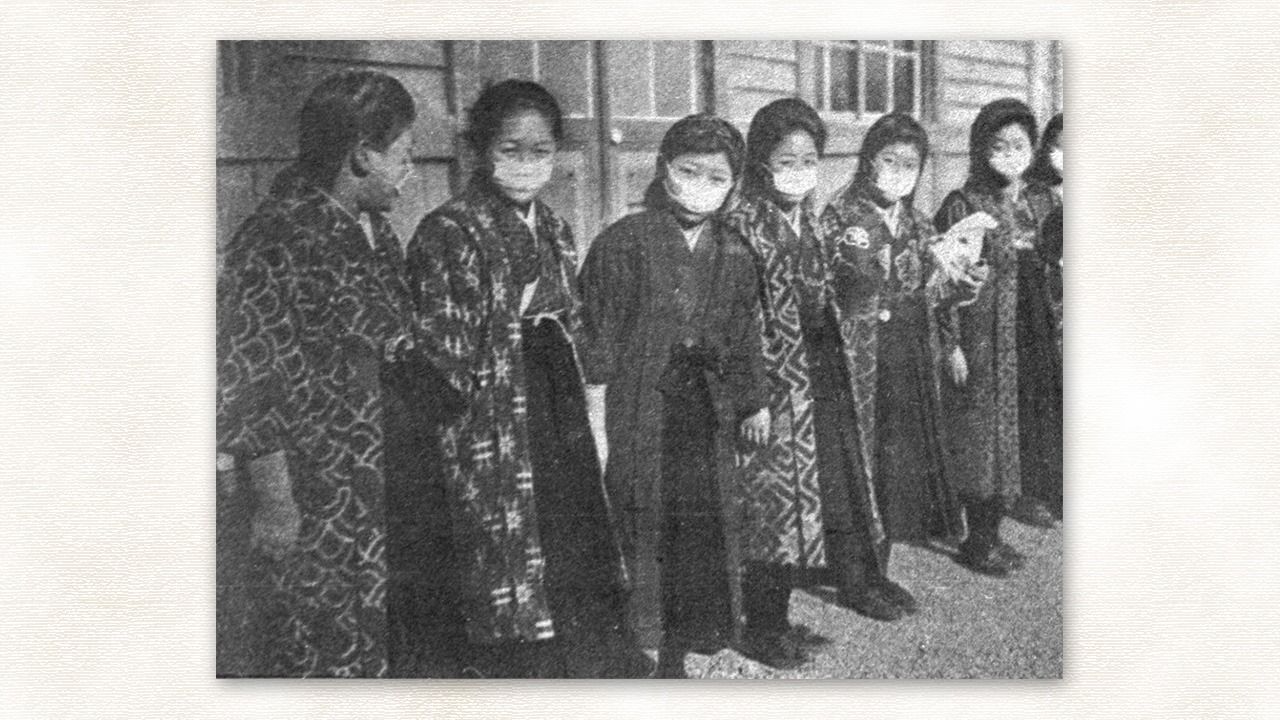

(Originally written in English. Banner image: Students wear masks to protect themselves from influenza in February 1919. © Mainichi Newspapers/Aflo.)