Ozu Yasujirō: A Director’s Time in Tateshina

Tateshina Story: An Unsuspected Encounter with Ozu

Cinema Culture History People- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

When you come to Tateshina in search of a volcanic retreat from the summer heat, you don’t expect to stumble upon an open secret in the history of cinema. I first landed here in late August 2020, fleeing oppressive weather and the pandemic, never suspecting that I would find myself in the last years of director Ozu Yasujirō’s creation and his retirement. Nor did I believe that it would take a few years to piece together every corner of the love story between the filmmaker and this natural enclave.

Forests of Japanese larch trees guard a snapshot of Japanese cinema in the early postwar decades. This explains why, 120 years after Ozu’s birth and 60 after his death, the thatched-roof, tatami-floored mountain villa where he devised his last films is still standing. Chino, the city on whose northern border Mount Tateshina stands near a lake of the same name, hosts a local film festival where the director is honored every year.

Lake Tateshina, near the villa where Ozu spent the last years of his life. (© Kodera Kei)

A Mountain Home of the Seventh Art

The original house occupied by Ozu during the 1950s stands intact near Lake Tateshina. Now a museum, it takes visitors back to the golden age of postwar Japanese cinema. Sitting in front of the house, I meet Fujimori Mitsuyoshi, who stokes the brazier and tells me about how the film director worked, his insatiable taste for the region’s refined sake, and the parties with filmmakers that were held here.

In 1956, the director of the 1953 Tokyo monogatari (Tokyo Story) rented the villa for his home office, surrounded by nature. He named it Mugeisō, combining art (gei) and nothingness (mu). This was a place, as Fujimori describes it, for him “to think about and prepare for his next work.” Until his death in 1963, he wrote and organized seven films there, accompanied by an ally, the screenwriter Noda Kōgo.

The entrance to the villa Mugeisō. (© Kodera Kei)

The interior of the villa. In the background, Fujimori Mitsuyoshi, seated in front of the fireplace, tells stories about Ozu Yasujirō. (© Kodera Kei)

The Tateshina Tourism Association decided to keep it intact and open it to the public. For the past five years, Fujimori has been in charge of keeping the house. A lover of Ozu’s films, he is also a keen observer of the gastronomic details in his life:

“Ozu would put a pot on the stove, add meat and vegetables, and season it with sake and soy sauce. He was very fond of sukiyaki. Then, if there was any left over, he would make curry rice but add too much sugar. He would offer it to his guests, even though he didn’t eat. No one could refuse. Nor could anyone say it was bad,” says Fujimori, who relates anecdotes from numerous sources. One night, though, he goes on, an actor in Banshun (Late Spring, 1956), Ikebe Ryō, let slip that the dish was inedible and broke the spell.

It took Ozu and Noda an average of three months to get a script ready, during which time they discussed and agreed on every step. It generally took them a month and a half to work out a plot, stitched together from scraps of conversations and their own lives. Then they would write the first draft of the screenplay, which Noda’s daughter would clean up, and Ozu would organize the cast. From time to time, if urgent business called, they would travel back and forth to Tokyo, then more than four hours away by train. (Today, it takes only two hours by limited express from Shinjuku Station.)

Unkosō, the Other Villa in the Clouds

In between making films was a desire for recreation and enjoyment in company. On August 18, 1954, at the height of his success, Ozu arrived in Tateshina for the first time, guided by Noda, who two years earlier had founded the nearby Unkosō, his own villa. He said that it was a base where the mountains “call to the clouds,” the meaning of the first characters in the name, and the clouds call to the people.

Interior of the rebuilt Shin-Unkosō villa, where the archive of the Tateshina Diaries is housed. (© Kodera Kei)

This place became a mecca for Shōwa era (1926–89) cinema, and many of Japan’s greatest filmmakers made their way here. After Noda, Ozu came, followed by Shindō Kaneto, the acclaimed director of Genbaku no ko (Children of Hiroshima, 1952). Ozu’s favorite actor, Ryū Chishū, also passed through. For these pioneers of Japanese cinema, muses appeared in this forest’s cool summers, vivid autumns, white winters, and sake year-round.

On the same day that Ozu arrived, Noda began a project that would last for years, the so-called Tateshina Diaries. All visitors were welcome to take part in the creation of this chronicle, which in the end amounted to 18 notebooks sketching out the moments between films: reflections, drawings, jokes, and life.

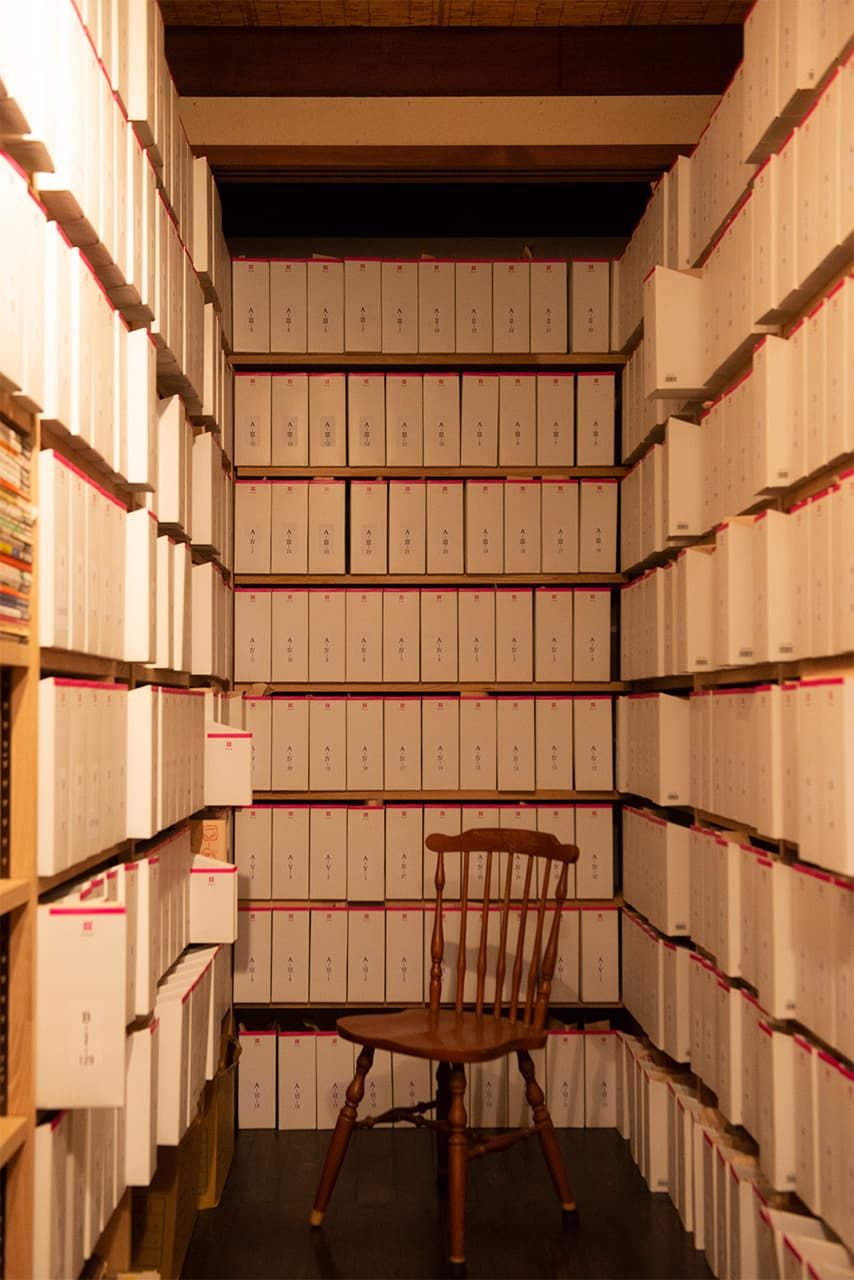

Seven decades later, in September 2020, the Shin-Unkosō provided a chance to celebrate the recovery of the diaries. Thanks to imaging technology, exact replicas of each sheet of washi paper in the notebooks have been produced. Yamanouchi Michiko, the executor of Noda’s documentary heritage, sees this achievement as a way to disseminate his artistic legacy.

The Shin-Unkosō has been transformed into the Noda Kōgo Museum and Noda Kōgo Memorial Tateshina Writers Research Institute, a meeting place for lovers and researchers of Ozu’s films. The archive contains the original scripts of Ozu’s masterpieces and other curiosities. A screen in one tatami room plays an unpublished film the pair shot in the area: Ozu is playing golf in the mountains, Noda is accompanied by his family, and so on. I go out into the forest that appears in the film and walk along the path that they walked together on many afternoons.

The archive of the Tateshina Diaries and other documents, at the entrance to the Shin-Unkosō. (© Kodera Kei)

Ozu’s Walk

Ozu was going to build his own house in Tateshina. He had already chosen the site and had the wood from old trees ready, but he would not see the completion of the project: he died of cancer on his sixtieth birthday, at noon on 12 December 12, 1963, in Tokyo. The lumber that would have sheltered him in the forest was not wasted, though, being reused by Noda to build an annex for his daughter Reiko.

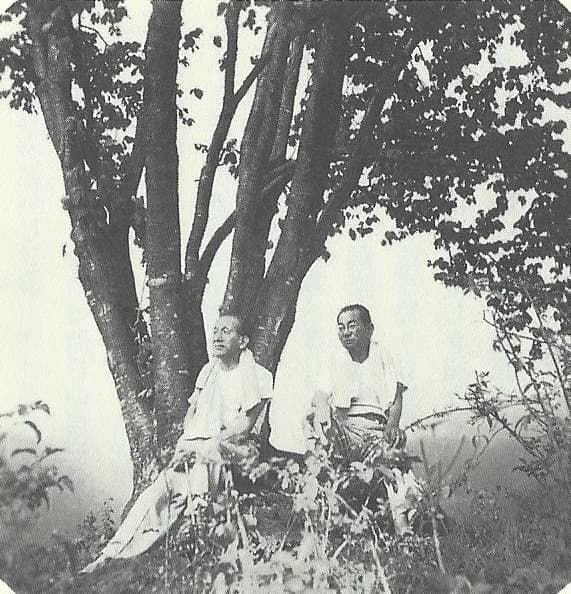

A walking course through the woods has been christened Ozu’s Promenade. The route leads through pine trees and other wooden villages to a river, ending at a single cherry tree, the only one growing in this forest. It is said that Ozu and Noda came up with the title Sōshun (Early Spring, 1956) there.

A sign announces that this is the path where Ozu and Noda used to walk. (© Kodera Kei)

Ozu and Noda would eat lunch, nap briefly, and reinvigorate themselves with a daily walk, during which they visited this cherry tree. Sometimes they were accompanied by Noda’s wife Shizu, his daughter Reiko, or the many friends who came to visit them. It was a unique route and indispensable part of the director’s life.

A small wooden altar stands at the base of the tree’s trunk, filled with small bottles of sake. Such offerings are customary at grave sites in Japan; are these left by anonymous Tateshina villagers, or admirers in search of inspiration, or some of Ozu’s younger relatives, who continue to visit the place admiring their uncle every year?

Ozu and Noda sitting by the lonely cherry tree. (Courtesy of the Noda Kōgo Memorial Tateshina Writers Research Institute.)

The cherry tree as it stands today, in the early autumn of 2023. (© Kodera Kei)

Thermal Baths and Good Drinks

We know from photographs and records that, during their stays, Ozu and Noda frequently visited Shin’yu Onsen to relax in the precious hot springs. It was a short walk from their villas. The fame of the hot springs that gush from the volcano goes back centuries, and their healing effects and natural surroundings have long attracted travelers from all over. The lodge itself, founded in 1926, is today home to an imposing library with 30,000 books.

Exterior of the Shin’yu Onsen. (© Kodera Kei)

The interior of the hot spring lodge. (© Kodera Kei)

Daiya Kiku, or “diamond-chrysanthemum,” was the name of Ozu’s favorite sake. As a great fan of the local drinks, he was captivated by this delicious local sake, in addition to the nature and the warmth of the people.

In September 2023, Toda Shuzō, the only sake brewery in Chino, is still in full operation in the city. Barrels of fermented rice welcome visitors. The secret is the local ingredients, a combination of water from Mount Tateshina and rice from the fields. Takahashi Yūsuke, in charge of brewing, explains that to commemorate the 120th anniversary of the director’s birth, they have launched a special edition using an original recipe.

The brewery still produces Daiya Kiku sake, Ozu’s favorite. (© Kodera Kei)

Daiya Kiku launched a special commemorative bottle of sake to mark the 120th anniversary of the director’s birth. (© Kodera Kei)

A Unique Film Festival

The love that the founder professed for this place is today reciprocated by its inhabitants. At an exhibition space within a stone’s throw of Chino Station, the town displays pieces of the Ozu story: a bulky film camera, old furniture, old photographs, and of course sake pots, with other keepsakes.

You can also see posters of the local film festival that has been held in Chino since 1998 in honor of Ozu. The director’s work crossed borders, and his filmography is now the subject of studies all over the world. Over the years, many film directors have acknowledged the great influence of Ozu’s works, such as Germany’s Wim Wenders, Hong Kong’s Stanley Kwan, and more recently, Spain’s Celia Rico Clavellino.

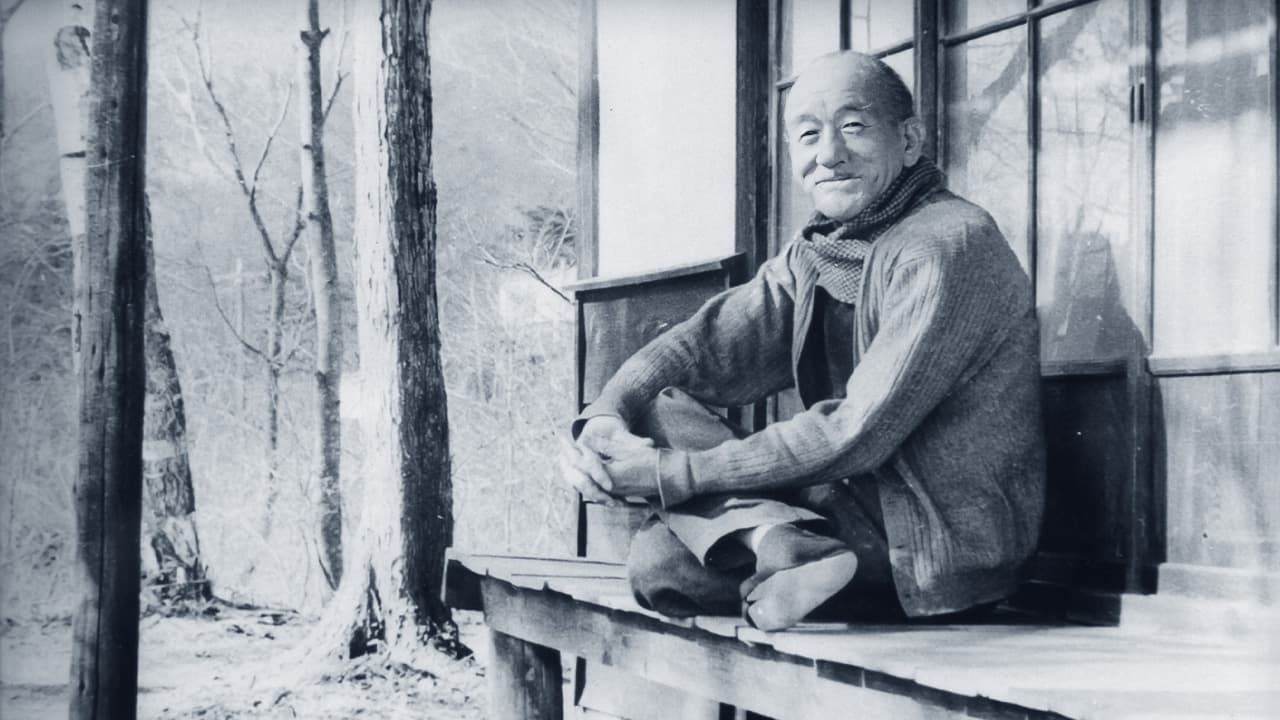

At the back of the exhibition room is an old camera, a gift from Ozu for his nephew Nagai Hideyuki, who as a child shared many moments with his uncle. In the summer of 2022, the octogenarian Nagai told me that when he received the complex machine, he didn’t know how to use it. But one of Ozu’s most iconic photographs, standing in front of a grove of trees in rubber boots, was taken by it. This image was used in 2023 by the Tateshina-Kōgen Film Festival to commemorate the artist’s 120th birthday.

The camera Ozu gave his nephew, displayed in a small museum next to Chino Station. (© Kodera Kei)

I leave Tateshina when autumn is just around the corner. The volcano remains impassive to the passage of time, oblivious to the secrets hidden in the forests. But the locals are custodians of history. Ozu’s past is safely tucked away.

(Originally written in Spanish. Banner photo: One of the photographs of Ozu Yasujirō displayed as part of the Tateshina-Kōgen Film Festival. Courtesy of the Noda Kōgo Memorial Tateshina Writers Research Institute.)