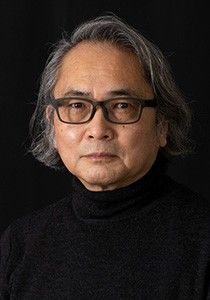

Capturing the Secrets of Light and Shadow: Photographer Muda Tomohiro

Culture Art Guide to Japan- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Capturing the Classics of Japanese Sculture

One of Muda Tomohiro’s most remarkable photographs is one he took of the standing Mujaku (the bodhisattva Asanga) at the temple Kōfukuji in Nara. The sculpture, a national treasure, is one of the masterpieces of Japanese Buddhist art. In Muda’s picture, it is hard to believe that you are looking at is an image carved out of wood in the twelfth century. The veins standing out on the temples, the wrinkles around the mouth, the look of peace and quiet resolution in the eyes . . . The picture conveys a breathtaking sense of reality, as if the great Buddhist teacher has been brought back to life and is standing there in front of your eyes.

Standing Statue of the Bodhisattva Asanga (Mujaku) (© Muda Tomohiro)

The picture of the Asanga figure graces the cover of the 2020 Tomohiro Muda Buddha Universe, which compiles Muda’s photographs of some of the greatest masterpieces of Buddhist art. (© Muda Tomohiro)

Muda remembers well the day he encountered this statue’s visage and took its photo, all in the course of just 10 minutes or so. He was in Nara to take pictures for a major exhibition on sculptor Unkei to be held at the National Museum, Tokyo, in autumn 2017. Muda was working with a sizeable group of people from the temple, museum staff, and his own assistants—between 10 and 20 people in all. As the morning came to an end, he felt that things had gone as well as could be expected, and went to lunch feeling reasonably satisfied with his work so far.

He checked his phone to discover a missed call from an old university friend. When he returned the call, he was shocked to hear his friend tell him: “They’ve amputated my right leg. The whole thing.” Muda stood dazed and oblivious as his assistants bustled about discussing plans for the afternoon. He couldn’t take anything in.

He drifted back to the Hokuendō, the temple’s Northern Round Hall, where he noticed that a door that had been locked all morning was suddenly standing open. Inside, autumnal sunlight streamed low through the open door, glinting off the floor and bringing out the lines of the sculpture in exquisite detail.

“This is it!” he thought.

There was no one else in the hall; the rest of the team were still busy with preparations outside. Using a telephoto lens, he fired off a rapid sequence of photos without reflection or hesitation. It wasn’t something he had been aiming for; certainly nothing he could have planned. But for those 10 minutes, he had lost all awareness of conscious thought or deliberate planning. In a sudden flash of inspiration, he was open to receive the secrets the sculpture had bequeathed.

When Silent Subjects Speak

When a photographic subject begins to yield its secrets, it is as though the subject is giving you permission to take your photographs, Muda says. Go ahead, shoot. And when you hear that message, you obey.

“It’s not a conscious thing. The subject is transmitting something rich and profound. My job is to become a receiver, ready to pick up on whatever message the subject wants to transmit.”

It’s a state of mind far removed from daily concerns—an experience of being “in the zone,” akin to the state of “no mind” prized by Zen meditators and martial arts practitioners. Muda calls it putting the brain in neutral. “Your consciousness is lowered, and you’re not thinking about things as you would normally be.” When drawing close to a subject he wants to photograph, Muda says he always tries to orient himself toward his subject and remain as open as possible to what it wants to tell him. Buddhist images, art, architecture . . . Muda’s photography has specialized in inanimate objects imbued with a mysterious “aura” or soul. All of them have a message to convey. Muda’s job is to use his camera to capture that message. It is a stance that never changes, whatever kind of subject he is working with.

What is it that Muda senses when he takes on this kind of antenna-like sensitivity? According to the photographer himself, what he picks up on is something that lies within the subject: “memories of prayer, memories of time.” For one project, he traveled to some of the areas of Tōhoku that were devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011, and photographed objects left behind by people who lost their lives in the disaster. Muda says he felt the memories of the people who had owned the objects coming through to him strongly, along with frozen memories of the terrible hours immediately after the tsunami hit.

A house slipper swept away by the tsunami presents a different face when found years later. From Toki no ikon: Higashi Nihon daishinsai no kioku (Icons of Time), in which Muda photographed objects left behind by the Great East Japan Earthquake. (© Muda Tomohiro)

The weight of this accumulated memory is even more powerful in the case of a Buddhist image that might be a thousand or more years old. The sculpture seems to carry an accumulation of memories dating back to Unkei (1150–1223), who made the image as an expression of his own faith, through all the many generations of people who have stood in front of the image, hands joined in prayer. The accumulated weight and power of those centuries of memory releases an enormous wave of energy: Muda says his job is to synchronize himself with this energy and make sure that he is ready to receive it when it comes.

No Medium for Self-Expression

Not that Muda himself always saw things this way. When he was a student at Waseda University, he approached Tōmatsu Shōmei (1930–2012), a photographer he admired, and asked to be allowed to study with him. Tōmatsu brushed him off unceremoniously. But they remained in touch, and the older photographer would occasionally give Muda his opinions on his work. One day, he said: “You think of photography as a means of self-expression, don’t you? Let me tell you: it’s not suited for that at all.”

At first, Muda struggled to understand. “His pictures were the epitome of self-expression! I wondered what he was talking about.” These doubts were only resolved two years later. After graduating from university, Muda spent a total of 18 months living in a Sherpa village in the Himalayas of eastern Nepal.

“I realized that the world outside was so much wider and deeper than anything inside me—for me to think that photographing this vast world could be a form of self-expression was just vanity. I needed to make myself receptive to the world and learn to pick up on messages that could not be expressed in words—and somehow to capture them in my photographs. That was my job, my mission.” Muda describes the time he spent in the Sherpa village as “an experience that fundamentally shook my understanding and changed the way I look at the world.”

An image from The Land of Sherpa, 1990. (© Muda Tomohiro)

Finally, what Tōmatsu had told him made perfect sense. “Photography is not a medium for self-expression.” The words resounded with the ring of truth and have been part of his artistic faith ever since.

Becoming One with Particles of Light

The photographs Muda had taken in Nepal were published in 1990 as The Land of Sherpa. This was followed by several volumes that focused on churches and monasteries in Europe: Romanesque: Sacred Buildings in Light (2007), Citeaux (2012), and Romanesque: Those Lurking in Light and Darkness (2017). The word “light” (hikari) in Japanese occurs in the titles of many of his collections.

For Muda, nothing is as important as natural light. His fascination dates to childhood, when his grandfather took him to Nara to visit the old temples. He would stand transfixed for hours, staring up at the silent Buddhas atmospherically delineated in the eternal twilight of the prayer halls. “It was as if I could see the particles of light. I felt myself being absorbed into this mass of light particles. And I always felt in synch with the messages that were being sent out by what I was looking at.”

This feeling became a firm conviction after his experiences in the Sherpa village. In the afterword to his first book, Muda wrote in the following terms about his experiences with light:

Perhaps it was the interplay between the alternating diffusions and concentrations of light that often gave me a strange kind of vertigo. Looking at the world with my camera, I felt as if I were standing at the entrance to another world. And I often felt this other world crossing the boundaries and spilling over into this one.

The light in Muda’s work sparks recognition across national borders and religious differences. When he held an exhibition in Paris of his photographs of Romanesque architecture, many of the people who visited the exhibition were astonished. “You have captured the light exactly as we always felt it in these churches since we were children,” one said to him. “How it is possible that an outsider like you could grasp and understand this unique sense of light so well?”

Gentle light streams through small windows into the unadorned, crepuscular nave of a church or monastery—and somewhere there, between the light and shadow, lurks a sense of the divine. The response the photos had in France is proof of how effectively Muda Tomohiro has trained himself to act as a receiver, picking up on the light that comes from the accumulated memories of the generations who have prayed here for more than 800 years.

From Citeaux (2012). (© Muda Tomohiro)

Fragments of the Secrets of the Universe

Muda began his career in the days of film. The arrival of digital cameras marked a turning point.

In the film era, taking pictures cost time and money: the more you took, the more time and money you had to spend developing your pictures. You needed to have a clear idea in advance of the picture you wanted to take, and shoot sparingly. By doing away with these considerations, the digital era changed everything. “You could concentrate on just taking pictures . . . and sometimes these strange things, like fragments of the secrets of the universe, would appear in your shots—things you could never have captured if you had been consciously trying to achieve that effect.”

The first time he used a digital camera was to take pictures of a sculpture by Unkei, where the narrow interior of the temple made working with a large film camera impractical. At a certain moment, sensing something in the “aura” of the statue, he turned the lens clicked the shutter. When he looked at the liquid crystal display, he was astonished to see that the camera had captured exactly what he had felt. He remembers the surprise clearly to this day. “Wow,” he exclaimed audibly to himself, “Something amazing has shown up in this image!”

At exhibitions, he is often asked whether he waits for the perfect light, but he dismisses the idea. “I never do anything like that.” He doesn’t make plans in advance. “When I’m on a shoot, I walk around the object I want to photograph—and take pictures subconsciously in response to something in the light that catches my eye at certain moments.” This style has remained unchanged throughout his career, even as the evolving technology of digital cameras has widened the possibilities for photography.

The photographer allows himself to be led, without deliberate planning, and the emotional power he shares with his subject reverberates through his photographs to reach a wider audience. In this way, his antennae become more attuned than ever to the silent signals of memory and the past that linger in places both sacred and profane. Muda’s work will no doubt continue to invite us on a journey into this secret world of light and shadow.

From Yungang Grottoes (2005). (© Muda Tomohiro)

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview by Kondō Hisashi of Nippon.com. Text by Sumii Kyōsuke of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Taken at the Komazawa University Museum of Zen Culture and History during the interview. © Kawamoto Seiya.)