A Walk Around the Yamanote Line

From Nippori to Tabata: A Rougher, Real Side of Tokyo to Explore

Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Gritty Charm in the Yamanote’s Northeast

Today’s walk starts at the northern edge of Nippori Station, on the Shimo-Goinden Bridge, better known among rail enthusiasts as a “Living Train Museum” as it stretches like a balcony over the city’s restless veins. Stand there for just a few minutes and you’ll see nearly every kind of train riding along a dozen or more sets of tracks, including the Yamanote and Keihin-Tōhoku lines, along with the Takasaki Line heading north toward open country; the sleek Keisei Skyliner flashing past on its way to Narita; and—most thrilling of all—the Shinkansen streaking beneath your feet. It’s said to be the only place in Tokyo where you can look down on a bullet train.

On weekends, the bridge fills with camera-toting train fans, families with children, and casual strollers. About 2,500 trains pass through here every day, a continuous choreography of steel and speed.

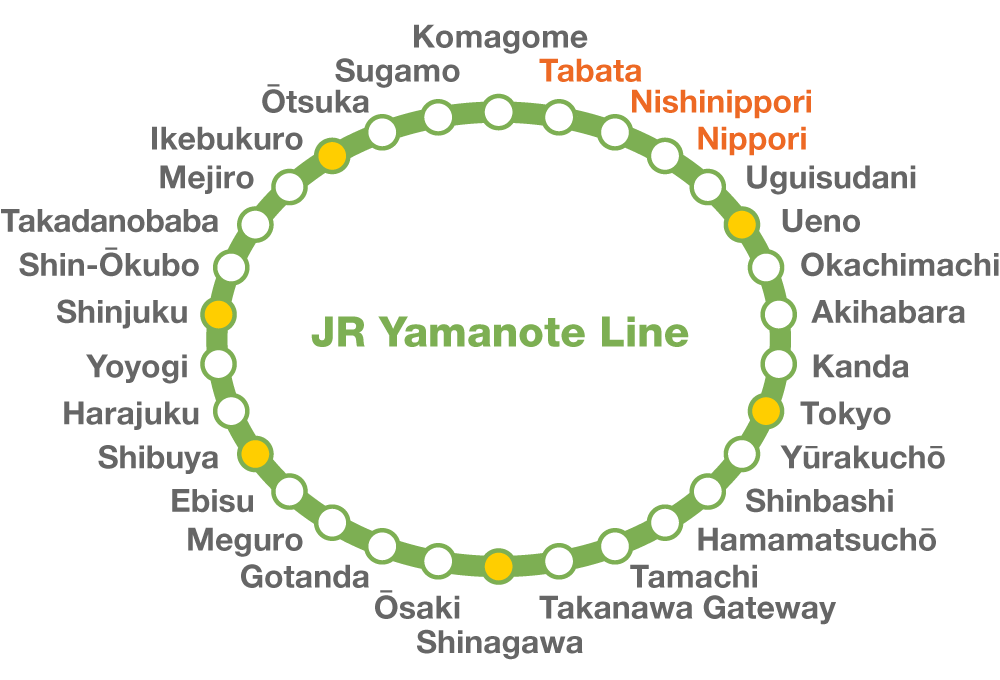

The stations on the Yamanote line stations loop. (© Pixta)

Closing my eyes, I try to forget the rail tracks and buildings, will the noise away, and imagine how the place looked like during the Edo period. Beyond Nippori and Nishi-Nippori, the land opened onto the low-lying marshes of what is now the city of Arakawa—a landscape of reed beds, rice paddies, and the shifting waters of the Arakawa, the main river flowing through this plain. Three or four centuries ago, this area teemed with natural life, home to red-crowned and white-naped cranes that waded through the shallows. These elegant birds, symbols of longevity and good fortune, were sometimes hunted for the tables of the elite, appearing in kaiseki banquets or ceremonial feasts. Though the wetlands have long since been reclaimed by flood control projects and urban expansion, traces of that watery world survive – in old place names, in local stories, and perhaps in the faded memory of cranes once rising over the fields.

“Sunset Village” or “Village Living from One Day to the Next”—both are possible translations of Nippori, gentle names that evoke slowness and calm. Standing here now, among the towers and tracks, it’s hard to imagine such a village ever existed. Nippori’s east side is all hard surfaces, grays and blacks of the buildings and the asphalt in which they are embedded. The overall feel is an ungiving, unbendable, impersonal environment, only broken at night, when the dark descends on Tokyo and the city is illuminated by the advertisements that in their intrusiveness have come to shape the look of the modern city.

Hovering above the bus terminal and taxi stands, the Nippori-Toneri Liner station, all glass and concrete, brings a faintly futuristic shimmer to an otherwise suburban landscape. This automated guideway transit system, which uses the same type of rolling stock as the Yurikamome we saw in Shinbashi, was designed to improve access to the northeastern reaches Tokyo once underserved by rail.

In new-looking Nippori, high-rises loom behind the Nippori-Toneri Liner station. (© Gianni Simone)

As part of the station area redevelopment, three major high-rise buildings were constructed to reshape the district’s skyline: the 40-story Station Garden Tower, completed in 2008 together with the train line, and two additional towers that together form a unified urban core. These buildings signaled a shift in the area’s architectural character, echoing the mixed-use formula—part residential, part commercial, part transit hub—that has sprouted like weeds across Tokyo. Amid of all this, much of the Shōwa-era landscape has been lost.

Sweet Tastes Lost to Time

Until not long ago, Nippori not only looked but even felt quintessentially shitamachi. In the heart of the district once stood Dagashiya Yokochō—Candy Store Alley—a bustling warren of narrow lanes lined with candy and toy wholesalers. It began as a thriving market space in the early postwar years, taking shape as Japan’s economy came back to life. Wooden row houses flanked both sides of the passages, and by 1954 such alleys buzzed with more than a hundred shops.

Nippori’s convenient location made it ideal for commerce: goods could easily arrive from Chiba and Ibaraki, and the station itself served as a natural crossroads. In those lean postwar years, children clutching coins would flock here, drawn by the bright packaging and sugary smell of dagashi—cheap sweets that offered a small taste of joy amid scarcity.

But as Japan grew more prosperous, tastes shifted toward Western-style confections. Convenience stores and video game arcades gradually replaced the candy alleys as children’s sanctuaries. The number of wholesalers dwindled rapidly, especially in 2004, when the area was cleared for redevelopment. When I visit the area, only one is left: Ōya Shōten, now located inside Station Garden Tower. Never mind, I leave the store with a bag full of Baby Star Ramen (a crispy, chicken-flavored, dried ramen snack), Morocco Fruit Yogul (sweetened shortening with a hint of yogurt flavor, served in tiny plastic tubs), and Fushigi na Gumi, the “mystery” gummy that changes flavor when you combine colors.

Nippori and Nishi-Nippori are separated by just 500 meters—the shortest distance between stations on the Yamanote Line. It’s about a 7-minute walk, unless one gets curious and starts exploring the anonymous backstreets near the viaduct. While Nippori has the sheen of recent redevelopment, the scenery gradually changes as I make my way northwest toward Nishi-Nippori: snack bars (sunakku, as they are called in Japan), pubs, and older rusty buildings. A particular corner even looks like a piece of the Berlin Wall, but maybe it’s just my twisted imagination.

Between Nippori and Nishi-Nippori one may be forgiven for being reminded of Cold War-era Berlin. (© Gianni Simone)

On a corner, I come across a gray, slightly weathered structure with a curious little place called TUC Shop, its yellow signboard popping like a cheerful exclamation against the concrete. It takes me only a quick online check to solve the mystery. I walk on, and as I suspected, I find a pachinko parlor 50 meters down the road. A pachinko parlor is a noisy, neon-lit arcade packed with vertical pinball-like machines, where players launch silver balls in hopes of winning more—often exchanged for prizes or tokens. It’s part game, part ritual, and wholly hypnotic.

When you see one of these places you can be sure you will find a pachinko parlor around the corner. (© Gianni Simone)

TUC (Tokyo Union Circulation) Shops are discreet prize exchange counters found near pachinko parlors. Due to Japanese gambling laws, pachinko parlors cannot pay out cash directly, so players receive small prizes, which they can exchange for money at nearby TUC Shops. This system, known as the “three-shop system,” maintains a legal separation between gambling and cash payouts by involving three entities: the TUC Shop buys the prize items from the gambler; a wholesaler buys the prize items from the TUC Shop and then sells them back to the pachinko parlor, completing the loop. The unassuming TUC outlets thus play a key role in keeping the pachinko industry within legal bounds.

Far from Tokyo’s Shining Center

After crossing the curving railway tracks at the Jōban Line level crossing, I follow the viaduct but get distracted by the scene in a side street: love hotels, massage parlors, pubs, and hostess clubs. In one case, the same building is shared by a karaoke box (private room rental style), a teppan (grilled dishes) izakaya, and a whole range of “nightlife playgrounds”: New Diamond, Ambitious, Picasso, and Dears among the names when I walk by (these clubs being known to change hands, and names, rapidly). There’s enough to satisfy any kind of appetite.

The area in front of Nishi-Nippori Station is a jumble of elevated train lines, pedestrian walkways, and four-way car traffic channeling a steady stream of buses, taxis, and delivery trucks all converging into a kind of infrastructural vortex: relentless, and visually chaotic. It’s urban life at its ear-splitting, lung-congesting worst. Yet there’s a certain perverse beauty to it. The whole scene feels like a living diagram of Tokyo’s dense, unyielding, and brutally efficient metabolism.

North of Nishi-Nippori, the city sheds its polish even more completely. The houses grow older, with bowed balconies and satellite dishes clinging to rusted railings. Warehouses and small factories wedge themselves between residential lots, their façades marked by faded company names and external staircases that zigzag like urban doodles. Truck depots spill into narrow streets, blue bins stacked behind chain-link fences, and utility pipes snake across walls like veins. Rail tracks multiply, vanishing into the industrial haze, bound for the deep suburbs. It’s a zone of labor and slow decay, with the odd whimsical corners, like a glass case of figurines sitting like a small shrine in front of a house, amid the grit. The neighborhood feels less manicured, more lived-in, its charm accidental.

The gritty cityscape is sometimes interrupted by odd whimsical corners, like a glass case of figurines in front of a house. (© Gianni Simone)

The last 500 meters of my walk is a slow, gradual ascension to Tabata Station. The station itself sits on the lip of the Hongō Plateau, where the upland neighborhoods of Komagome and Sugamo taper off into the lowlands of Nippori. Here the city changes altitude almost imperceptibly, yet I can feel the shift in the terrain: the straight slope pulls against my legs, and the rail tracks on the left grow gradually smaller. I also feel the familiar thrill of crossing into the unknown: the northern section of the Yamanote Line runs through parts of Tokyo still foreign to me.

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Suwa Shrine offers another great view of railway traffic in the Nippori area. © Gianni Simone)