Katsushika Hokusai: The Woodblock Virtuoso Who Enthralled the World

Culture History Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In a famous afterword to an edition of his illustrated book One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), then in his seventies, gave an insight into his artistic spirit.

From the age of 6, I was in the habit of copying the forms of things, and many of my pictures have been published since I was 50, but everything I created before 70 was worthless. At 73, I came to know a little about the structure of birds, animals, insects, and fish, and the botany of trees and plants. Thus, when I’m 86, I’ll make further progress with my technique, at 90 I’ll master this art, at 100 I’ll reach the level of the divine, and at 110 every dot and line I paint will appear to be full of life.

These words demonstrate how he was never complacent, and always seeking to improve his art.

Finding His Path

Hokusai’s career as an ukiyo-e artist began in 1779, when he was 18. He became a student of Katsukawa Shunshō, who was known for his portraits of kabuki actors, and created his own pictures of actors, many of which survive to the present day. Hokusai, who used many names during his lifetime, was known as Shunrō at this time (however, this article will generally refer to him as Hokusai). His 1791 portraits of Ichikawa Ebizō and Sakata Hangorō on stage show a high level of polish, indicating that he got off to a smooth start in the ukiyo-e world.

Portraits of Ishikawa Ebizō (left; courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art) and Sakata Hangorō (right; courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase).

After the death of his teacher Shunshō in 1792, Hokusai’s position within the Katsukawa school appears to have become difficult. The likely cause is thought to have been a falling out with Shunkō, the student who became the new leader of the school; in 1794 Hokusai became the successor to another ukiyo-e artist called Tawaraya Sōri, himself taking the name Sōri. Then, rather than producing work in the main ukiyo-e genre of commercial nishiki-e prints, he threw his energies into producing surimono, which were single-sheet works that were not sold directly to the public, such as simplified calendars distributed by merchants at the start of the year and event invitations. While they were also woodblock prints, Hokusai met the demand for the lighter, more delicate colors that were favored in these works. During this time, he was also illustrating books of kyōka (humorous poems), which similarly called for delicacy and refinement. Hokusai was a major painter in these two genres, both of which reached a high artistic level from around the end of the eighteenth century.

Den’en kōraku (A Trip to the Country) from Otoko tōka (Men’s Stamping Song). (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

New Directions

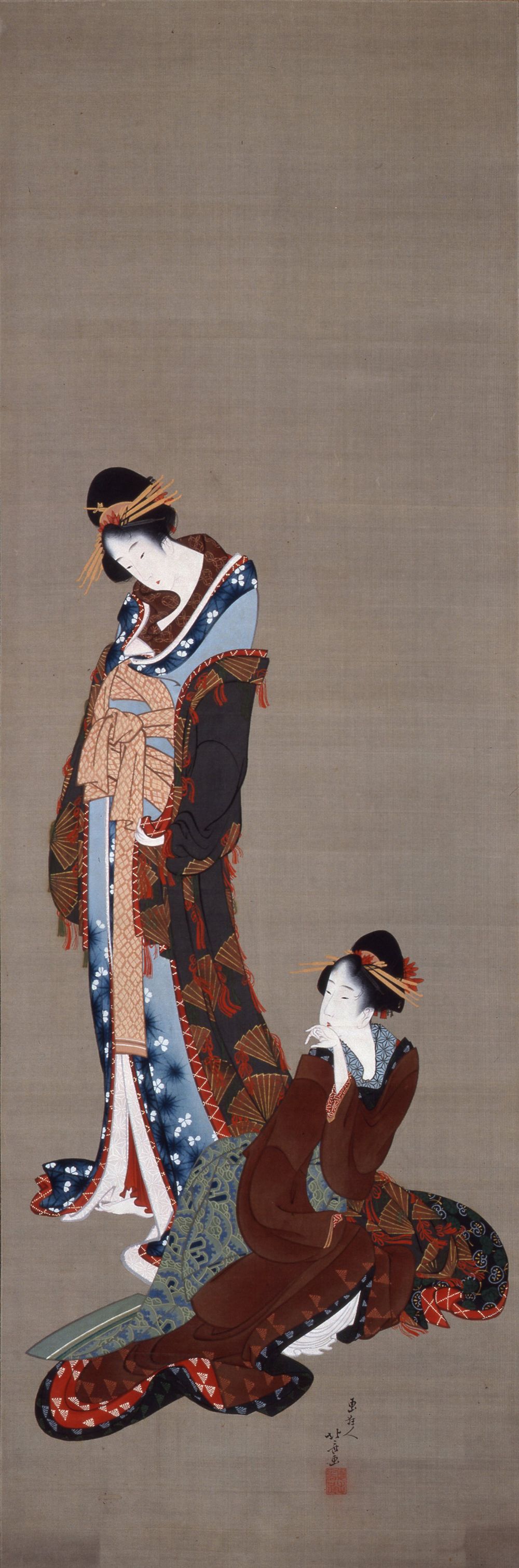

In 1798, he passed on the name Sōri to one of his students, and began calling himself Hokusai, the name by which he is now widely known. From his latter days as Sōri, for a decade or so, his works in the genre of bijinga (pictures of beautiful women), with their tall, slim, and elegant figures, won him huge popularity. A book published in 1800, when the great bijinga artist Kitagawa Utamaro was still active, praised Hokusai’s work as comparable to that of the respected author Santō Kyōden for representation of beautiful women. His hand-painted Sōri-style bijin, named after his artistic sobriquet at the time he started painting them, are highly regarded today.

Nibijinzu (Two Beauties). (Courtesy MOA Museum of Art)

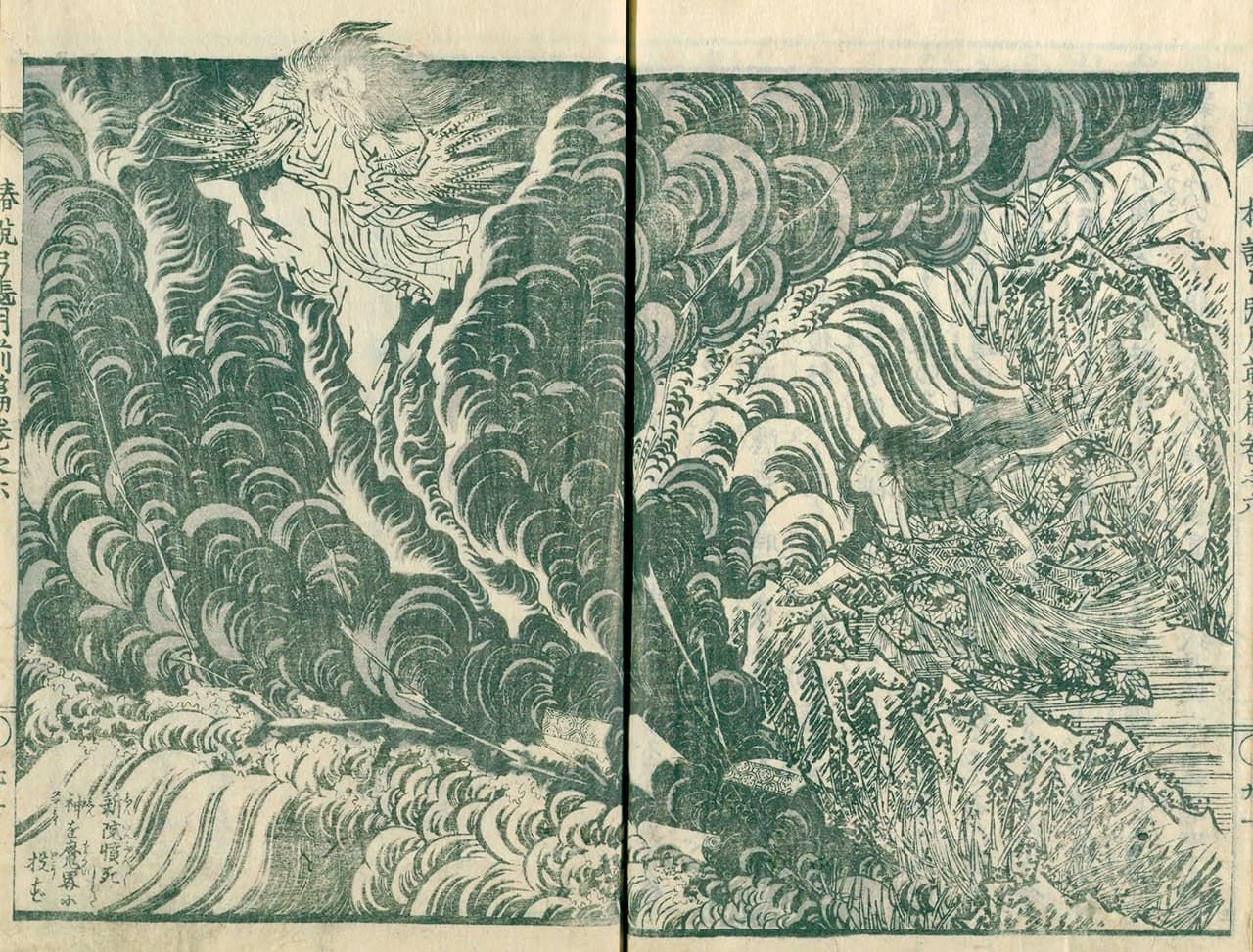

One popular genre of books in the Edo period (1603–1868) was the yomihon, thanks to authors like Kyokutei Bakin; this was story-driven literary fiction, but illustrations were very important in boosting sales. Hokusai was a leading illustrator, his tightly knit compositions matching the complex literary style of a text that incorporated Chinese words, while his dynamic brushstrokes bring to mind contemporary gekiga manga, and he made effective use of inky darkness to depict mysterious happenings. Bakin was known for his scathing comments, but while he noted Hokusai’s “contrary” nature in not simply following the instructions of the writer, he highly rated the artist’s level of skill. They worked together on Strange Tales of the Crescent Moon, which is one of the masterpieces of the genre.

An illustration by Hokusai from Chinsetsu yumiharizuki (Strange Tales of the Crescent Moon) by Kyokutei Bakin. (Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection)

Around almost the same time that he was producing illustrations for yomihon, Hokusai took on a new challenge. This was creating “Western-style” woodblock prints that aimed to reproduce the texture and density of depiction of Western copperplate engravings and oil paintings. After pioneering works by painters like Shiba Kōkan and Aōdō Denzen piqued his curiosity, Hokusai produced a number of series representing the scenery of Edo and other areas in a style different from the nishiki-e of the time, deploying techniques such as shading and copperplate hatching or colors seen in oil paintings. In this novel form of expression, the artist’s rakkan seal is written in hiragana that mimics Roman letters. While not always successful in the market, it had a considerable influence on ukiyo-e artists’ depiction of scenery, including Hokusai’s own students. This was a base from which he would develop toward later scenic works like Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.

The Western-style work Yotsuya Jūnisō (Jūnisō at Yotsuya). (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

Hokusai and Fuji

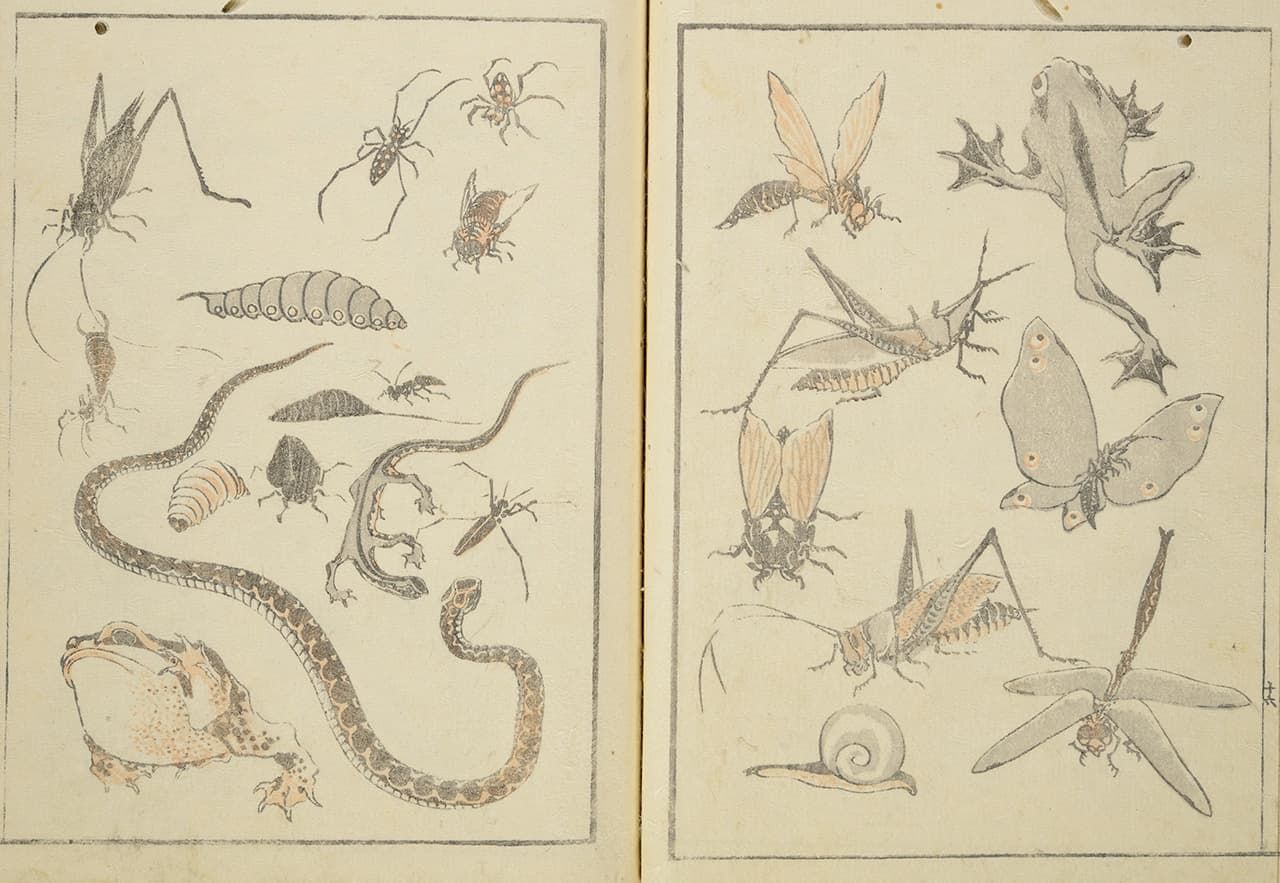

Hokusai passed his most famous name on to a student in 1815, and began calling himself Taito. The previous year had seen the publication of the first volume of Hokusai Manga, which would make the name Hokusai known around the world. This contained sketches of people, animals, insects, fish, flowers, and many other kinds of things, and was designed as a collection of models for art students to use in their practice. As Hokusai had established himself as a master artist, there was massive demand for his sample pictures, and subsequent volumes followed, with the fifteenth and final one being published in 1878, around three decades after Hokusai’s death. There were also caricatures that were more for enjoyment than simple models. The forms of the people, birds, fish, and insects give a firm impression of Hokusai’s individuality, and their creative impact appealed to both Japanese artists and later ones from the West.

First volume of Hokusai Manga. (Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art)

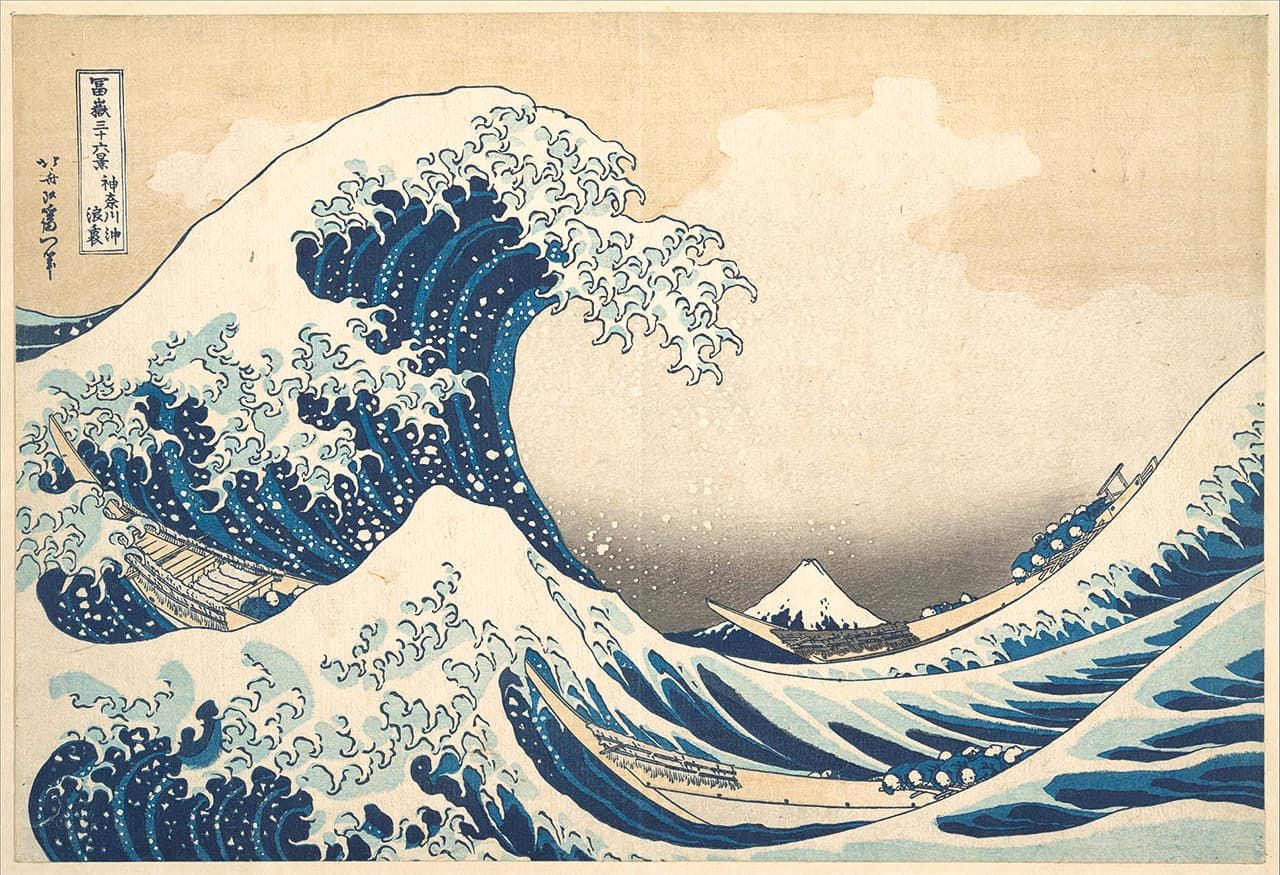

Around 1830, Hokusai produced Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, including The Great Wave off Kanagawa, which still enthralls people around the world today. Mount Fuji had a special place in the hearts of Edoites, and the series’ presentation of the iconic peak in a range of compositions from different locations and in varied weather conditions was a big break for Hokusai, helped in part by abundant use of the imported synthetic pigment Prussian blue, which had gained popularity for its vibrant color. Landscapes were formerly a minor genre within nishiki-e, compared with representations of actors and beauties, and the publication of a series of dozens of pictures must have entailed considerable risk. About a decade earlier, Hokusai had taken on the name Iitsu, and the artist was by now an elderly man of 70. His bold effort to take on a new genre demonstrated how he did not plan to rest on his laurels.

Kanagawa-oki nami ura (The Great Wave off Kanagawa) from the Fugaku sanjūrokkei (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji) series. (Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The success of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji established the landscape genre within woodblock art, and spurred Hokusai on to further series, including A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces and Famous Bridges in Various Provinces. Other artists like Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Utagawa Hiroshige also tackled the genre.

Shimotsuke Kurokami-yama Kirifuri no taki (Kirifuri Waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke) from the Shokoku taki meguri (A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces) series. (Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago, Clarence Buckingham Collection)

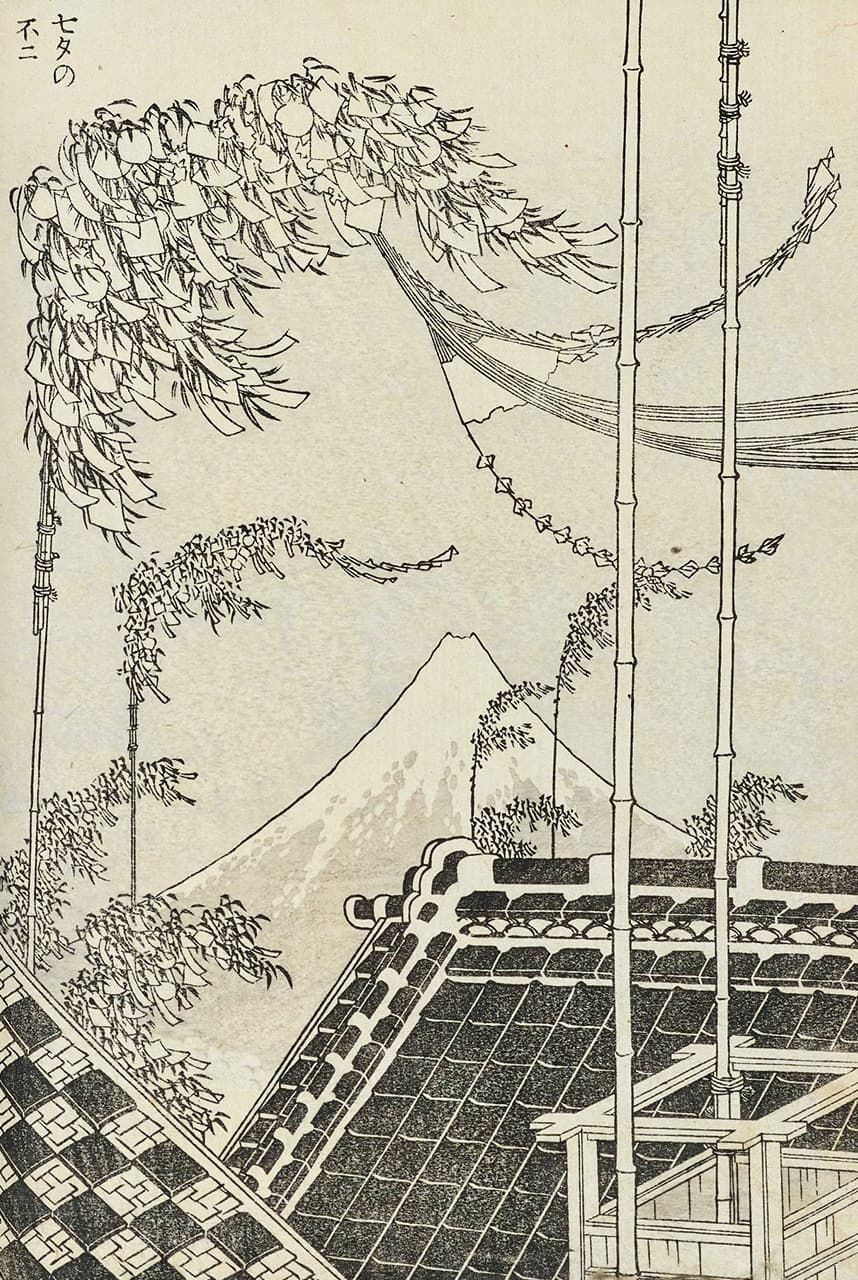

Through the 1830s, Hokusai also produced series centered on flowers and birds, playing a leading role in establishing these further genres. In 1834, he adopted the name Manji, which he used for his famous afterword to One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. As well as scenery, this multifaceted illustrated book also looked at myths and literature associated with the sacred peak. The audacious composition greatly enlarged aspects of the foreground to highlight comparisons with the mountain in the distance.

Tanabata no Fuji (Fuji at Tanabata) from Fugaku hyakkei (One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji). (Courtesy Tokyo National Museum/Colbase)

The influence of Hokusai’s landscapes extended outside Japan to the West. Notably, in France this included woodblock prints by Henri Rivière and glassware by Émile Gallé.

Les Trente-six vues de la Tour Eiffel (Thirty-Six Views of the Eiffel Tower) by Henri Rivière was inspired by Hokusai’s Mount Fuji landscapes. (Courtesy Yamaguchi Prefectural Art Museum/Uragami Memorial Hall)

Hokusai, who had hoped to live until 110, died in 1849 at the age of 88. Three years before his death, he is reported as having still been a hardy walker, and his creative spirit and painting ability seem to have remained undiminished until the end, as he completed several great works in the last year of his life. He often described himself as “mad” about painting, but Hokusai could more accurately be characterized as deeply dedicated to the art, with his firm sense of purpose and ongoing innovation.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 19, 2025. Banner image created based on a portrait of Hokusai by his student Keisai Eisen, taken from a book by Kimura Mokurō. Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection.)