Manga Worth Having on Your Shelves

“Chainsaw Man”: A Blood-Drenched Antihero for Today

Culture Entertainment Art Manga Anime- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Un-Jump Manga in the Pages of Jump

Chainsaw Man began serialization at the end of 2018 in Weekly Shōnen Jump. The tankōbon version is a huge hit, with over 30 million copies in print, and it has seen both a television and theatrical anime adaptation.

The protagonist is 16-year-old Denji, a boy living in poverty in a ramshackle hut. When his father dies, Denji is forced to take on his debt to the yakuza and becomes a “devil hunter” to make money. Hunting down and killing bizarre creatures and evil demons is dangerous work, but profitable.

However, the yakuza double-cross and try to kill Denji as part of a secret deal with a devil. On the brink of death, Denji makes a pact with his companion, Pochita, the doglike chainsaw devil. Denji is restored as the half-human, half-devil hybrid Chainsaw Man. He uses the overwhelming might of this new form to make short work of the yakuza.

Then, he attracts the attention of the Japanese government’s devil hunter force, the Public Safety Division, and is recruited to fight even greater threats.

In contrast to the usual Shōnen Jump style that emphasizes “friendship, hard work, and victory,” this is a decidedly “Un-Jumplike” manga from the very start. The biggest reason for that is Denji’s clear characterization as an antihero.

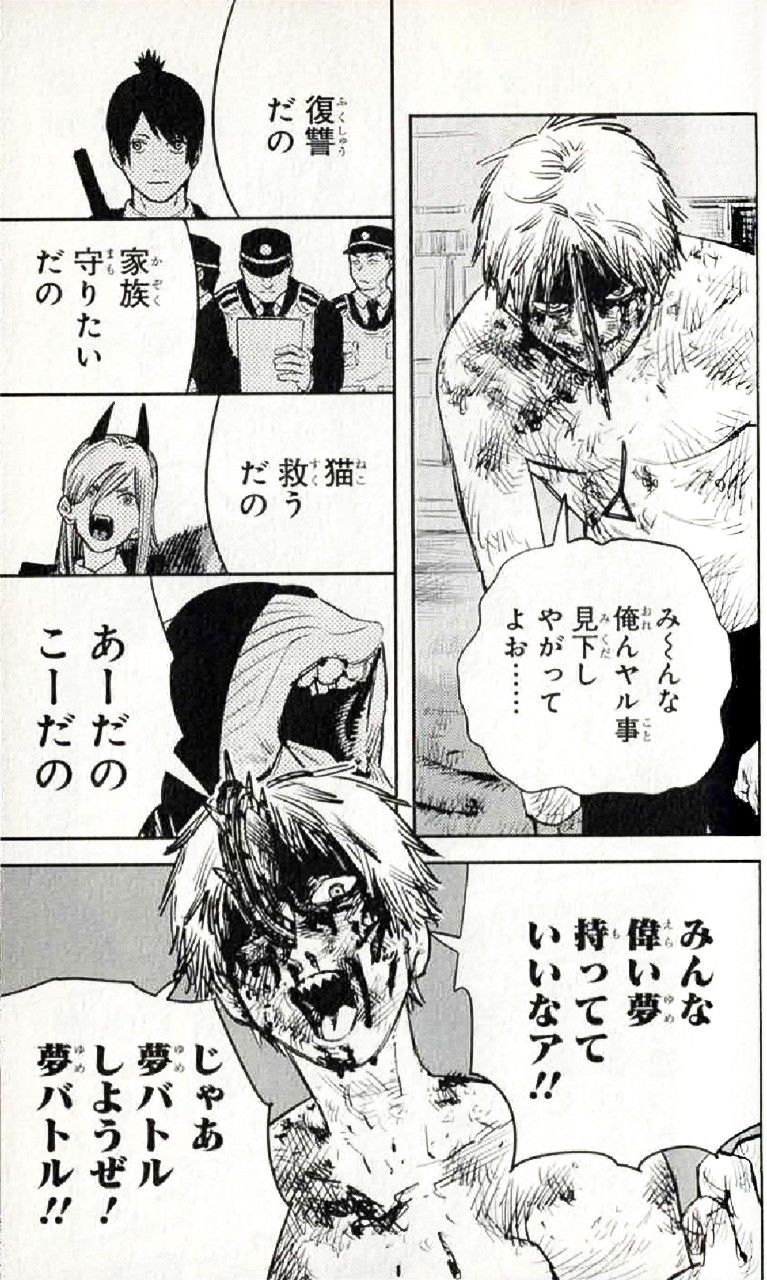

From Volume 2 of Chainsaw Man. (© Fujimoto Tatsuki/Shūeisha)

Desperation Meets Pop Sensibilities

Denji—who could not go to school, who was loved by no one, and who lived in such poverty he sought to sell his organs—wanted nothing more than a “normal life.” His desires are simple: spreading jam on toast and eating it with Pochita, a girl to hug, and playing video games with her in his room. His fights with devils are largely orchestrated by his female superior, Makima, in the Public Safety Division, who plays on those hopes to manipulate him. The contrast with other Jump protagonists, like Kamado Tanjirō of Demon Slayer or Midoriya Izuku of My Hero Academia, is stark.

Author Fujimoto Tatsuki said in an interview with foreign press that he thought making it a “Jumplike manga” could carry a risk of his work getting buried within the pages of the magazine. He goes on, “Because of that, I tried to retain much of my individuality as a creator while making only the structure and characters Jumplike.” So, although there is that strategic element to the decision, it’s impossible to ignore his individuality as a creator.

The sight of Denji with massive chainsaws protruding from his head and arms is an unforgettable one, but it seems more sinister than cool. In a conversation with Fujimoto, musician Yonezu Kenshi—who provided the theme songs for both the TV and theatrical anime—talks about his own reaction to the sight. “When (the chainsaws) rip out of each of his arms . . . it comes across as a form of self-harm. It’s not the kind of thing I’ve seen in any other work.” He also remarks: “It’s dark and serious, while also having a sense of eccentricity. At the same time, it somehow appears to be pop.” That intersection between the misery of self-harm and an eccentric pop sensibility is where Fujimoto’s individuality really expresses itself.

Chainsaw Man fans are going global. Here, a cosplayer dressed as the titular character poses at Fan Expo Canada in Toronto in August 2023. (© Ayush Chopra/SOPA Images/Sipa)

Bouncing Between Arrogance and Self-deprecation

This work is not set in the twenty-first century. There are no smartphones, and the streets are lined with phone booths. There is a vague sense of the late 1990s. That would mean 16-year-old Denji was born in the early 1980s. In other words, this story lands right in the middle of Japan’s great job drought of the late twentieth century.

The job drought, sometimes called the Employment Ice Age, lasted from the bursting of the economic bubble in 1993 through around 2005. Many of the young people who entered adulthood in that period struggled to find regular work, and are referred to as the “Lost Generation.” Those roughly 17 million people are now in their late thirties to mid-fifties and have a significant impact on Japan’s public sentiment and politics.

One of the main sentiments that this generation shares is a pessimistic worldview that avoids holding out for big dreams, and a powerful sense of individual responsibility, where a person’s struggles in life are blamed on a simple lack of effort. Fujimoto Tatsuki, born in the early 1990s, has likely seen up close the gloomy worldview of the Lost Generation.

Denji bounces between reckless arrogance and self-deprecation, and his primary motivations are the three fundamental desires of sex, food, and sleep. There is something about that fact that resonates with the lost generation. And that truth may not be limited to Japan. People all around the world seem to recognize something in him that they can relate to.

The Touch of Genius

I also want to discuss the work’s antagonists, called devils. They first appear as unidentified monsters, but Denji’s boss Makima soon explains their natures. “All devils are born with names, and the more those names are feared, the more powerful the devil becomes.” In other words, the devils are the embodiments of concepts that people fear. Devils like the Zombie Devil or Bat Devil are straightforward, but others are harder to parse, like the Gun Devil, Control Devil, War Devil, or Aging Devil. These many devils are not only superbly designed, but also convey a sharp sense of social satire and give the work a certain philosophical abstraction.

The first section of the story, the “Public Safety Division” arc, concluded at the end of 2020. The second, which moved to the Shōnen Jump+ app and began serialization in 2022, has departed from the role of simple entertainment. Some fans are complaining that they no longer “get it.” But the chaotic direction portrayed seems to reflect the state of the times we find ourselves in today. This is yet another era of war, with the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza filling the news.

I believe that Chainsaw Man’s creator Fujimoto is the greatest manga genius since Akira creator Ōtomo Katsuhiro. That begins with the quality of his art. Ōtomo broke manga ground in the 1980s with a new three-dimensional style, evolved by artists like Shirō Masamune in the 1990s, and further updated by Fujimoto. It conveys a thoroughly cinematic vision, fitting to this modern age when every smartphone has a video camera, turning everyone into a videographer.

But what really demands consideration is the cold vision that Fujimoto brings to his fictional style. His previous work, Fire Punch (2016), was an unconventional creation, with a character who wanted to film the protagonist’s quest for revenge to make a revenge-tragedy story of his own, fictionalizing the story’s plot inside the story. Chainsaw Man takes similar metafictional stabs, with scenes openly poking fun at Blake Snyder’s famous scriptwriting guides, the Save The Cat trilogy.

Fujimoto is famous for creating scenes that pay homage to the author’s favorite movies, but that in itself is a signal to the reader of the story’s fictional nature. In other words, the manga itself works as both fiction and a metafictional critique of creative work. And that is perhaps the true essence of Fujimoto’s “individuality as a creator.” His web manga Look Back, adapted into a film in 2024, is about two young women aspiring to become mangaka. It stands as an easy to read and understand masterpiece, but I think it is Chainsaw Man that shows his true face.

Having said that, the fact that his work defies any easy interpretation is perhaps what truly makes Fujimoto Tatsuki, well, Fujimoto Tatsuki.

Film and TV Resonating with Youth

The theatrical release now playing across Japan is an extension of the television anime. Its magnificent fight scenes alone are worth the price of admission, playing out like a concentrated showcase of Japan’s anime prowess. The majority of the audience are in their twenties, and most leave the theater with a look of satisfaction. Apparently this work is resonating deeply with the younger demographic.

Chainsaw Man has won awards around the world. In Japan, it won the 2021 Shōgakukan Manga Awards Best Shōnen Manga award, and in the United States it won Best Manga at the Harvey Awards, the nation’s oldest comics prizes, three years in a row from 2021.

Anime adaptations of eight of Fujimoto’s early short works, including his debut piece A Couple Clucking Chickens Were Still Kickin’ in the Schoolyard, are in the middle of a limited domestic cinema run and will begin global streaming from November. This is another sign that Fujimoto Tatsuki possesses something that sets fire to the hearts of other creators of his generation.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Comic volumes of Chainsaw Man, originally serialized in Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine. © Fujimoto Tatsuki/Shūeisha.)