Sexual Harassment in the Japanese Media: Finding a Way Forward

Society Society Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Published in February 2020, the book Masukomi : Sekuhara hakusho (Sexual Harassment in the Japanese Media: A White Paper) details the stories of women working at newspapers and in broadcast media and publishing. Compiled by Women in Media Network Japan (WiMN), the work consists of a series of interviews in which the women discuss their personal experiences of sexual harassment along with other struggles and injustices they have faced over the course of their careers. The book offers an unprecedented opportunity to hear active professionals in the media address the subject of sexual harassment not as journalists covering a story but as individuals affected by the menace in their own lives.

The women in the book are from different generations and work in a variety of media fields. However, each speaks of the overwhelming prevalence of sexual harassment, not only within their companies but also while out conducting interviews and other professional assignments. Many describe how the situation has given rise to a culture in which female journalists must learn to deal with harassment as a matter of course. Feeling helpless to change their plight, many of the women have until now remained silent about the treatment they were forced to endure.

“Nothing to Get Worked up About”

According to Hayashi Yoshiko, a freelance journalist and representing facilitator of WiMN, newly hired journalists typically learn the ropes by covering the police beat for a local regional office. In the male-dominated professional environment, rookie reporters are expected to scout out potential sources and are under constant pressure from supervisors and senior colleagues, who are almost always men, to do whatever it takes to get the story. Young women with little professional experience often find it difficult to establish rapport with male sources, and this can easily lead to cases of sexual harassment. In the recently published White Paper, many women say that they suffered sexual harassment from co-workers, supervisors, as well as from the police and other information sources.

Hayashi recalls a jarring story from when she was starting out as a reporter with the Asahi Shimbun. As the newspaper’s first female reporter assigned to the police beat in Niigata Prefecture, she found it difficult to get officers to take her seriously and subsequently struggled to obtain the scoops her editors expected. Faced with an especially uncooperative source, she reached our for help. “I can still clearly recall the so-called advice my supervisor gave me,” she recounts. “He looked straight at me and blurted out: ‘You have to grab the guy by the balls.’ Basically, he was telling me to do whatever it took to get on good terms with the person so he’d give me the information I was after.”

Hayashi joined the Asahi in 1985, just before Japan passed the Equal Employment Opportunity Law aimed at guaranteeing equal opportunities between men and women in the workplace. There was little awareness of sexual harassment among the general population at the time. Hayashi was the only woman out of seven reporters assigned to her local bureau and she describes the work environment then as a “boys’ club.”

In 2018, Hayashi became one of the founding members of the WiMN following a prominent case of sexual harassment in April of that year involving a female journalist from TV Asahi and the vice finance minister. The weekly magazine Shūkan Shinchō reported the vice minister using inappropriate language and making unwanted advances to the journalist, including asking to hug her and touch her breasts, unleashing a scandal that eventually resulted in his removal from office.

One aspect of the incident that concerned Hayashi was the attitude of Asō Tarō, the finance minister and deputy prime minister. “At a meeting of House of Councilors Committee on Financial Affairs, Asō said that since the vice minister had expressed regret for his behavior, there was no need for serious disciplinary measures and a warning was sufficient as sexual harassment was not a crime,” she explains. Hayashi felt that she could not stand by while the second most senior figure in the national government described sexual harassment as a peccadillo that was not worth making a fuss about. Eventually, public outcry forced the ministry to launch an investigation into the incident, but Hayashi recognized a familiar pattern. “The investigation itself was riddled with problems, with no consideration for the rights of the journalist, and with the ministry calling on her to disclose her identity as part of the investigation.”

The journalist had originally approached her superiors and suggested that they report the incident. But after it became clear that no one at the network was interested in responding to her grievance (TV Asahi did later submit a written complaint to the Ministry of Finance), she shared her story with Shūkan Shinchō, providing the magazine a recording of her interview with the vice minister that corroborated her allegations of misconduct. However, even this too prompted criticism from some quarters, leading to a widespread feeling among female reporters that something had to be done. Fellow journalists organized rallies to protest against these open attacks on a victim of sexual harassment, and this gave rise to the group as a way to show unity and solidarity.

Why More Victims Don’t Speak Up

WiMN was founded on May 1, 2018, and currently has more than 100 members. The group organizes various activities, including rallies to encourage stronger legislation to prevent sexual harassment and residential study group meetings. Most members have chosen not to disclose their names out of concern that their involvement in the group might result in problems for them at their companies or with sources and clients. The book also changes the names of most of the interviewees. In her afterword, Tamura Aya, a journalist with Kyodo News who served on the editorial committee for the work, notes that many of the women interviewed struggled with the psychological burden of talking about their experiences, and some broke off correspondence partway through the project or simply found it too traumatic to talk about the past despite wanting to contribute.

Others reacted differently, though. Hayashi says many in the group expressed regrets about not speaking up sooner. “There was a feeling among many friends I talked to that if we’d said something sooner, we might have saved the female journalists who came after us from suffering the same pain.” At the same time, she stresses the importance of not blaming the victim, saying that the most insensitive thing to do to a woman who has gone through sexual harassment is to criticize her for remaining silent or suggesting that not speaking up somehow lessens the culpability of the harasser. She insists the problem is with the way society makes women who dare to speak up suffer the consequences of their brave actions. Several women in the book describe how they were relocated within their companies or bullied by their superiors after complaining about sexual harassment. Even without these concerns, talking about sexual harassment is a difficult act that inevitably involves digging up traumatic memories.

Hayashi says the risks of being sexually harassed are particularly high for female journalists. “Women can be the target of inappropriate remarks and actions not only by their coworkers in the office, but also the people they interview for stories,” she explains. “We want media companies to do more to defend their journalists against this kind of unacceptable treatment. Unless these companies take a firm stand, women will continue to endure harassment in the course of doing their jobs, and in some cases, suffer psychological trauma that can last their whole lives. Women working in journalism often get in touch with us to talk about the awful treatment they endure. Even after the incident at the Finance Ministry, many companies still have no system in place to support victims or to respond to cases of harassment.”

Even when women have female coworkers or older colleagues they can confide in, it can still be difficult for victims to get the help and support they need. Hayashi points out that many women in an attempt to get along in a male-dominated environment have learned to internalize the chauvinistic values of the system. “A lot of women seem to believe that they need to resign themselves to a caustic workplace environment, almost as though it is a necessary to sacrifice their dignity in order to concentrate on the more important work they want to do as journalists.”

Leaving the Asahi

Hayashi worked at the Asahi for more than 30 years, building up a solid track record over the course of a career that saw her move back and forth from the Tokyo head office and regional offices around the country. From around 2000, she began to focus on labor issues, including cases of death due to overwork and the problems facing part-time workers. She even worked as sectional editor-in-chief for a time, although she says she was never particularly driven by career advancement and was happy doing work she believed was worthwhile. In 2014, when she became a senior staff writer at the Tokyo head office, a position that in principle would allow her to work on whatever story she wanted, she suddenly found herself running up against a wall.

At the time, many young women were being scammed by “scouts” who lured them with promises of appearing on television, only to press their victims into performing in pornographic films once they had duped them into signing dishonest, exploitative contracts. Hayashi says she heard of the story through a group that supports victims and was horrified by the brazen disregard for the women’s basic human rights.

These scandals were hardly reported in the mainstream media and Hayashi says it was not easy to get the women to agree to be interviewed. Many were afraid that their identity would be revealed if they spoke to the media. Hayashi begged the male department head at the time to let her at least write an article to tell readers that the support group had received calls from as many as 100 victims. However, he turned down her suggestion on the basis that without interviews, the story would have no legs, something as a woman she felt confident was not the case. It was not until a year and a half later that Hayashi was able to arrange meetings with victims and write her article. This was after a lawsuit had been brought and the case had gone to trial. “If only we’d been able to publish earlier, we might have been able to warn people about what was going on,” she exclaims. “That thought weighs constantly on my mind.”

This was only the first of several incidents that Hayashi found difficult to accept. Describing herself today as a “belated feminist,” she says she was driven by a growing desire to learn more about the factors behind sexual harassment, sexual violence, and other gender issues. She would often work hard on articles about sexual harassment only to have her editors substantially cut the stories. Fed up with the situation, in November 2016, she responded to a call for early retirement.

Her last assignment for the Asahi was a series on natural disasters and gender. In one of her articles, she wrote about how in the wake of natural disaster, single or widowed women were frequent targets of sexual violence in evacuation centers, a chilling fact that Hayashi says she had to fight hard to get the paper to publish. Today, she continues to work as a freelance journalist while pursuing a doctoral degree. Her master’s thesis, written last year, was based on interviews with five women who had suffered sexual harassment.

Changing the Japanese Media

Of the 50 new graduates who joined the Asahi along with Hayashi, only eight were women, and of those only three remain at the newspaper today. Although women now make up a higher percentage of new hires in journalism, the ratio improved little for more than a decade. On April 1 of this year, the Asahi Shimbun issued a gender equality declaration, prompted by research showing that Japan was 121st place out of 153 countries in the Global Gender Gap rankings, its lowest position ever. In 2020, women finally made up 50% of the year’s new journalism recruits. According to an article carried in the Asahi the following day, women represented 19.8% of all employees in the company as of September 2019, but just 12% of managerial positions. The equality declaration aims to double the proportion of women in management roles by 2030. But a questionnaire in the book (based on data that was up-to-date at the end of September 2019) makes clear that newspapers, press agencies, and TV stations still suffer from many of the same problems when it comes to hiring and promoting female employees.

The book’s revelations about women’s professional experiences in the media casts an unforgiving light on the reality of life on the front lines of journalism. In many ways, the situation facing young reporters today is little changed from the one that women of Hayashi’s generation faced when they were starting out. Reading the interviews in the book underlines the seriousness of the predicament facing women in the media. Unless we strive to change the working environment for female journalists and improve professional standards across the industry, there is little prospect of bringing about the broader social changes that are needed to push Japan forward.

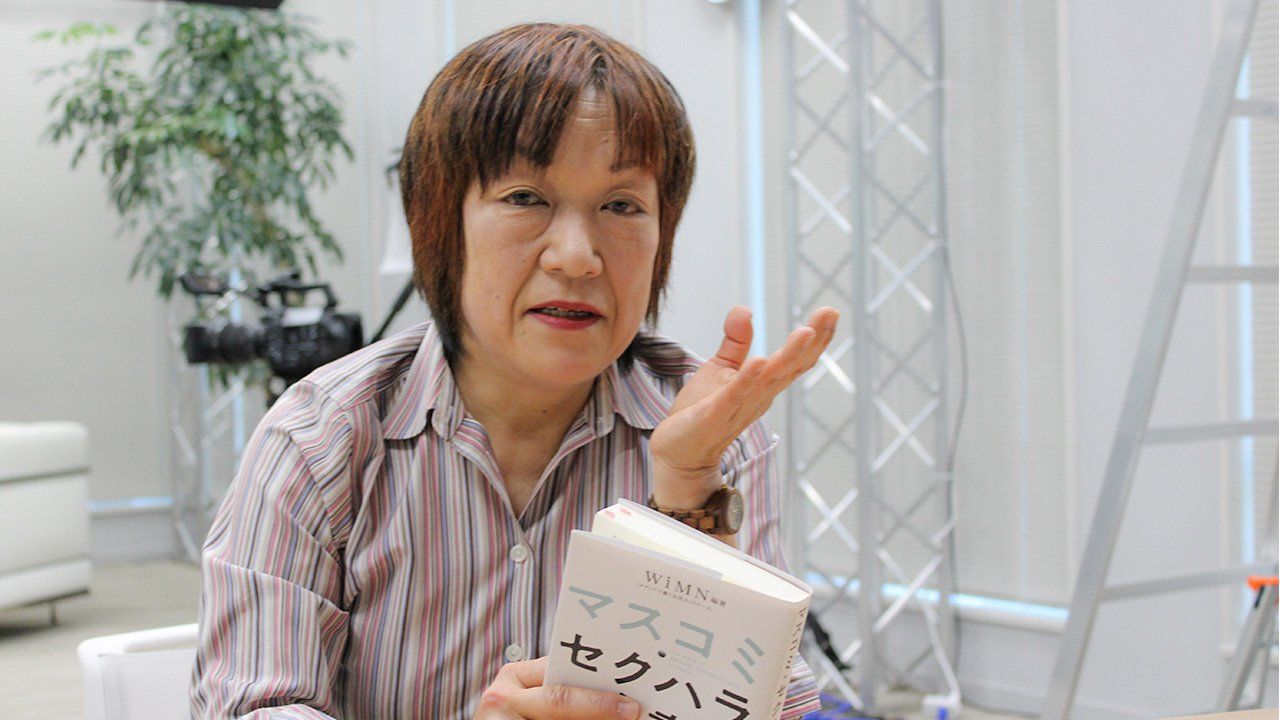

(Originally published in Japanese, based on an interview by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Hayashi Yoshiko, freelance journalist and founder member of WiMN.)