“No Special Attacks” Author Sakai Katsuhiko on Naval Officer Minobe Tadashi

Books History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Rational Man of War

“I was inspired to write this book by my encounter with Tsuboi Harutaka, a former fighter pilot who had served in the Fuyō Butai, a night-flight corps commanded by Lieutenant Commander Minobe Tadashi,” explains Sakai Katsuhiko, president and CEO of Jiji Press. “This was when I was in charge of our Fukuoka bureau, and I got the chance to interview him several times as part of a project to record the memories of those who had experienced the Pacific War first-hand. The Fuyō Butai was a naval air squadron that stuck with standard attack methods right up through the battle for Okinawa, when much of the Japanese military was resorting to tokkō, or suicide ‘special attack,’ tactics in a last-ditch attempt to defend the main islands. I found this fascinating.”

Minobe—the subject of Sakai’s book, Tokkō sezu (No Special Attacks)—seemed to be an ordinary military man. While he did make it into the elite Imperial Japanese Naval Academy, he graduated a middling ninety-seventh out of his class of 160. As the book explains, though, even this mediocre performance provided a window into the rational nature of a man who would go on to argue against the tokkō strategy—he was aiming for a position in the seaborne air forces, which tended to be looked down on in the Imperial Japanese Navy, because he figured this would give him a better shot at becoming a pilot.

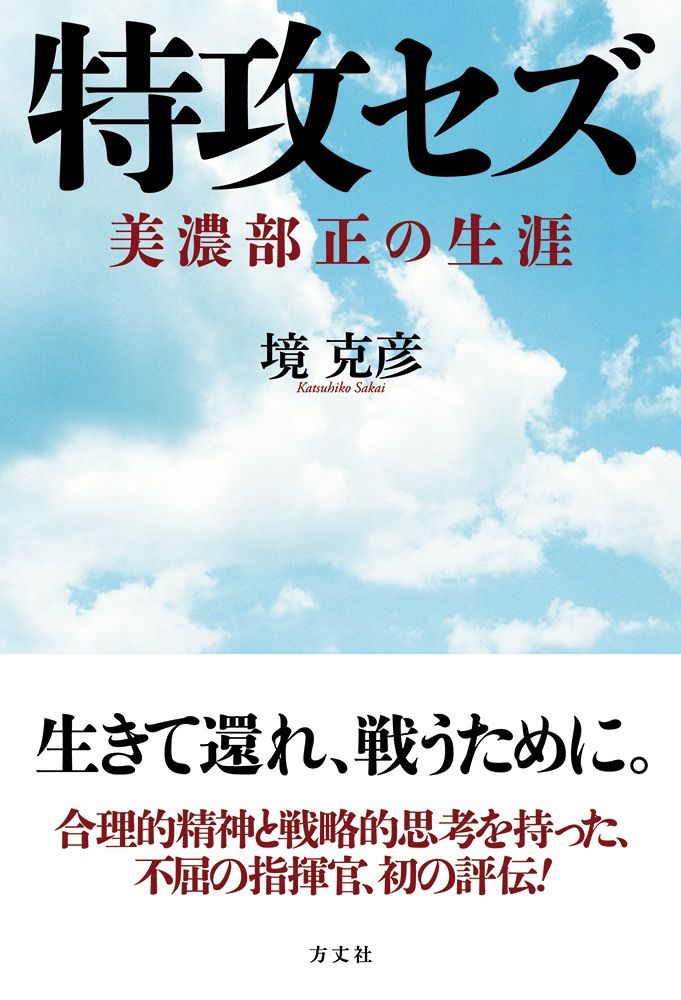

Tokkō sezu: Minobe Tadashi no shōgai (No Special Attacks: The Life and Times of Minobe Tadashi), written by Sakai Katsuhiko, was published by Hōjōsha in August 2017.

When Minobe, at the young age of 29, stood up in the meeting with the IJN leaders to oppose special attacks in the southern Japan theater, it was not from some sense of humanitarianism—and certainly not inspired by a pacifist streak. He understood that tokkō had its place as Japan’s defense method of last resort. But he also believed that the navy’s commanders needed to attempt all other methods before moving on to that solution, and was a forceful proponent of more conventional strategies as a result. At the meeting in question, he came in for a brutal verbal lashing from his superior officers, but he stood his ground, and in the end it was his proposal that won the day.

Taking to the Skies at Night

The pilots assigned to perform these suicide attacks have traditionally been held up as paragons of bravery. In fact, though, they were undertrained soldiers with poor equipment flung haphazardly into their missions. The majority of them never even managed to fly their aircraft into an enemy vessel, being shot down and crashing in the sea instead.

Minobe recognized this and came up with a new plan: night attacks. The Fuyō Butai he commanded was stationed at the Iwagawa airfield, located in what is now the city of Soo in eastern Kagoshima Prefecture. During daylight hours, the aircraft were concealed in the nearby woods, and cows brought out to graze on the fields, making the area look like a ranch. At night, though, the planes would come out of hiding, taking off to attack American forces to the south and returning to concealment before the sun rose. Given the US military might being brought to bear at this stage of the war, these sorties may have amounted to mere pinpricks, but they were nonetheless a rare spot of proactive Japanese strategy during a stage of the conflict when defeat seemed increasingly inevitable. And surprisingly enough, the Iwagawa base remained undiscovered by the American forces through the end of the war.

Fuyō Butai members pose for a commemorative photo at the Iwagawa base on July 5, 1945. Lieutenant Commander Minobe Tadashi is wearing white at center in the second row. (Courtesy of former Fuyō Butai member Tsuboi Harutaka; © Jiji)

A Technically Exacting Page-Turner

Above I describe Minobe as an “ordinary military man,” but among scholars of Japan’s military past, he is quite well known. When he passed away in 1997, at the age of 81, Jiji Press released a brief obituary describing him as a former general of the Air Self-Defense Force, the highest rank he attained in his postwar service. Sakai’s book, however, focuses more on his wartime career, beginning with his time in the Naval Academy and including copious details on the inner workings of the Imperial Navy, technical aspects of Japan’s aircraft, and more.

This does not put the book beyond the reach of the average, nonspecialist reader, though. Sakai—as I know well from my own time in Jiji Press, when he served in the same section as me—has a flair for illuminating writing that always struck me as highly advanced for one eight years my junior there. He has produced a clearly written, informative book that flows like an entertaining novel more than a nonfiction historical piece, and the pages seem to turn themselves.

I asked Sakai whether he considers himself a military geek, with the command of the specialist lingo he displays in his book. “Not at all,” he laughed. “In fact, I often found myself exhausted from all the research I did for it—the interviews I did with people who lived through those years, the reading of the materials I collected on the subject. I don’t want to write anything like this again!” The road to publication of this work was a long one, he explains, and indeed, the lists of individuals and organizations he spoke to, and his research bibliography, run into the triple digits. Many of the resources he relied on are not available for purchase, making this book a demanding one to have written.

An Unassailable Atmosphere

In the years since World War II, the tokkō special attacks have come under harsh criticism as an inhumane waste of young life on one hand, while becoming the subject of many stories praising the strategy as one of selfless sacrifice. Sakai’s book takes neither of these tacks, though. It focuses steadily on Minobe as a rational-minded soldier, examining how the Japanese military fostered an atmosphere where people who felt its approaches were wrong could say nothing aloud and portraying his struggles in the face of this mood.

I will let Sakai’s book speak for itself on the topic of this stifling atmosphere. “Once an overarching direction is set, no matter how illogical it might be, there is no way for a single individual to turn it aside, as anyone who has been a part of an organization can doubtless grasp. . . . When a particular atmosphere has taken shape, it gains the ability to slough off clear evidence and rational explanations that might go against it. It controls the process by which people make their decisions; it rules them, becoming a powerful stricture that prevents them from speaking freely. After the fact, when we seek to determine how decisions were reached, it becomes clear that the people breathing that atmosphere had no agency; it was the invisible atmosphere itself making the calls, leaving no room for individuals to take responsibility.”

Why Minobe?

Despite the era it describes, Sakai’s book does feature some characters worthy of admiration and even kind-hearted military superiors. At the same time, though, there is no shortage of commanding officers who cannot see the truth of the situation, or who lack all scientific understanding and capability. It was these people who contributed greatly to the creation of that terrible atmosphere of the times, sending countless young men to their deaths. The awful realization is that today’s Japan, not to mention the rest of the world, has yet to root out this very same problem.

Why did Sakai select Minobe as the subject of his work? Because, in his own words: “When you look into the history, there were actually plenty of high-ranking officers in Japan with critical views of the tokkō strategy. But they took great pains to air these views only in limited spaces, such as in quiet conversation with colleagues they knew shared their concerns. Minobe was different in the way he brought his objections out into the open, throwing them at the military’s top leadership at the conference table, and what’s more, getting them to listen to him. There was nobody else who accomplished that.

“I believe, frankly, that he was something of an outrageous figure. But the fact that there was a person like him in those dark times—as well as people at the top of the Imperial Japanese Navy willing to lend him their ears—strikes me as a saving grace.”

Sakai Katsuhiko at the Nippon.com office in Toranomon, Tokyo, on June 5, 2020.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Pilot Tsuboi Harutaka poses with his Suisei night fighter. Sakai’s 2015 interview of Tsuboi before his death inspired the author to write Tokkō sezu. Courtesy of Tsuboi Harutaka; © Jiji.)