A Humanitarian and an Officer: Sugihara Chiune’s Story Illuminated in New English Book

Books- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Talented Linguist Goes to Work

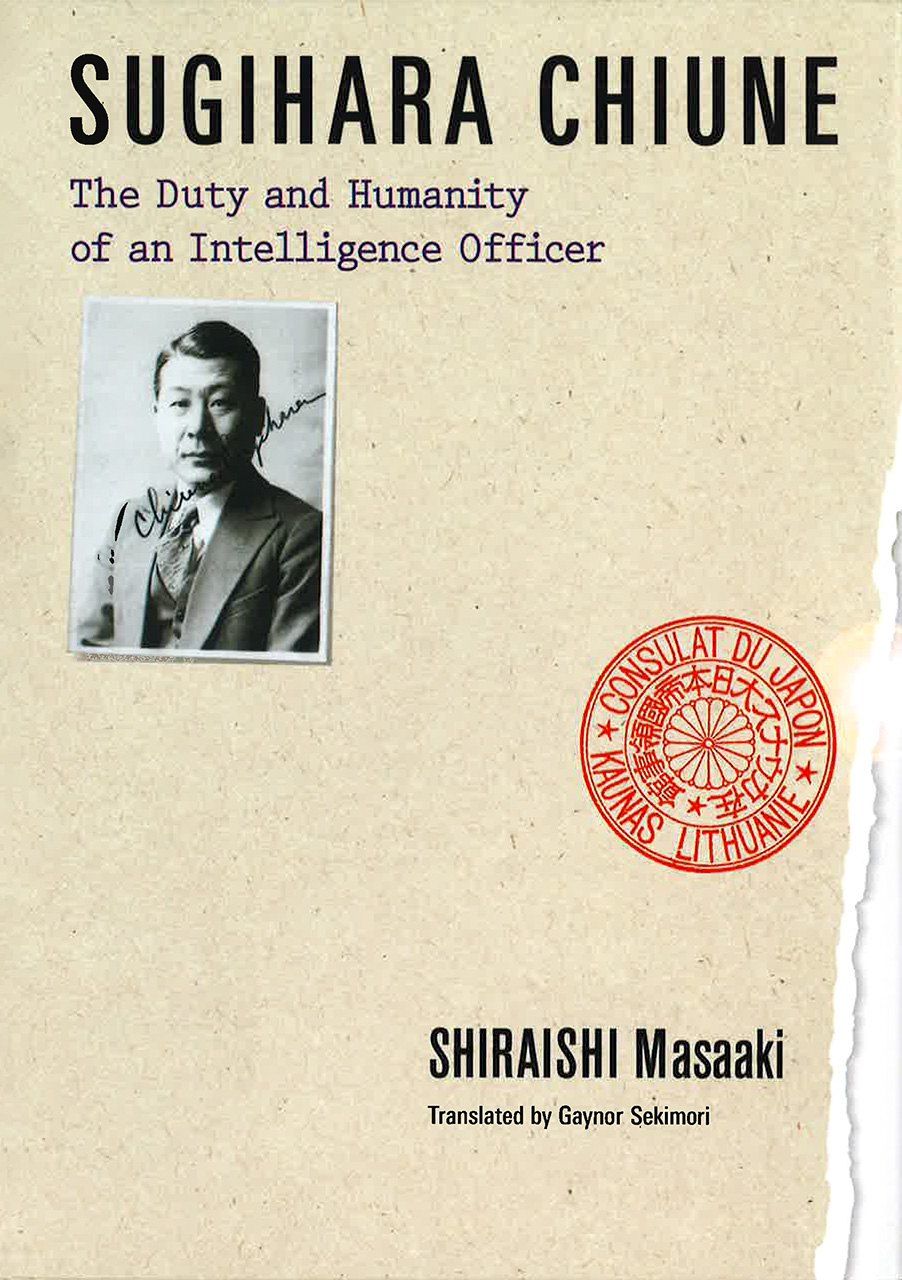

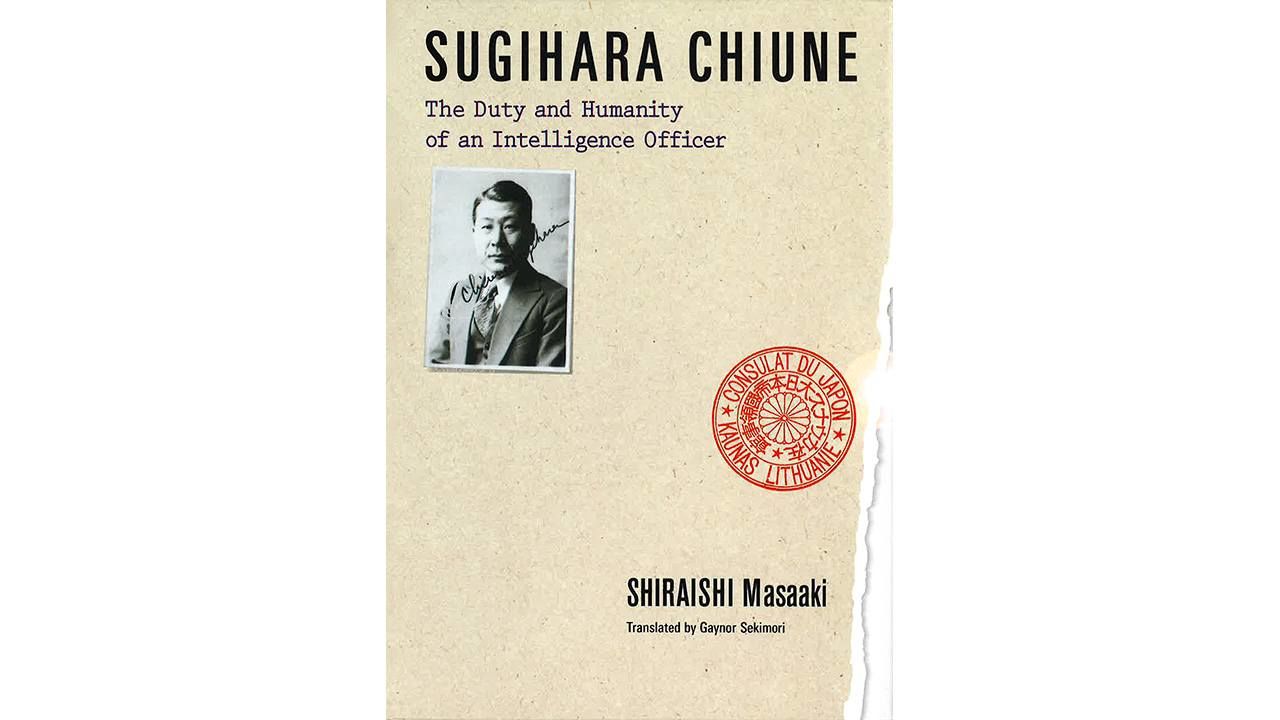

Shiraishi Masaaki, the author of the 2015 Sugihara Chiune: Jōhō ni kaketa gaikōkan, has worked for more than three decades in the Diplomatic Archives of Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His book has now been translated by Gaynor Sekimori, a research associate at the SOAS University of London Centre for the Study of Japanese Religions, and published in English as Sugihara Chiune: The Duty and Humanity of an Intelligence Officer. The work, an objective analysis drawing on the telegrams and reports filed by Sugihara (1900–86) during his time in Kaunas, Lithuania, and Prague, then Czechoslovakia, paints a fuller picture of the diplomat whose “visas for life,” issued in 1940–41, offered a lifeline to thousands of Jewish refugees in Eastern Europe.

The dawn of Sugihara’s diplomatic career saw him sent to Harbin, Manchuria, as a Foreign Ministry language cadet. In this city close to the Soviet border, built originally by Russians, he was to study the Russian language. He made good use of his time there, mastering the language to a high level while he befriended White Russians who had fled there following the Russian Revolution and began to develop his network of information sources on the Soviet Union.

In 1932, when Japan established the puppet state of Manchukuo, Sugihara was transferred to its Foreign Affairs Department, where he handled Soviet relations.

In 1935 the young diplomat cemented his status as a talented intelligence officer when he concluded negotiations over the reversion of the Chinese Eastern Railway—situated in northern Manchuria, an area under Russian influence—from Soviet control to Manchukuo ownership. He proved to be a hard-nosed bargainer, securing the CER for just a fifth of the price originally demanded by the Soviet side after he drew on his growing network to gather information including the number of freight cars the Soviets were pulling out of the railway.

The following year, he was tapped by the Japanese Foreign Ministry to serve as second secretary-interpreter at the embassy in Moscow, but the Soviet authorities took the unprecedented step of refusing a visa to this member of the diplomatic corps. He had evidently been declared persona non grata by the Soviet Union, which perhaps feared his talents and potential influence in its capital.

Sent to the Front of the Intelligence War

Shiraishi presents a detailed treatment of Sugihara’s activities in his European posts. In August 1939, on the eve of World War II in Europe, Sugihara was assigned to Kaunas, the temporary capital of Lithuania. In this Baltic state, close to both Germany and the Soviet Union, diplomats and agents from Britain, the United States, and the European powers were engaged in a fierce struggle to gain vital intelligence that could sway the events about to unfold. Japan, which had fallen behind in this race for data, sent Sugihara into this arena to make up lost ground.

Intelligence officers from the Polish government-in-exile, which had lost its state with the 1939 division of Poland by the Nazis and Soviets, approached Sugihara as he was striving to develop contacts in Lithuania. Many Poles felt an affinity for Japan due to its victory over the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5, and the nation had remained close to Japan, continuing to provide valuable information following Tokyo’s 1933 withdrawal from the League of Nations.

Poland was at the time home to Europe’s largest Jewish population, numbering 3 million to 4 million. Many Polish Jews fled to Lithuania following the September 1939 German and Soviet invasions. Moscow, however, had designs on the three Baltic states as well. In June 1940 some 160,000 Soviet troops were stationed in Lithuania, and foreign countries were ordered to close their embassies there. The Japanese consulate where Sugihara worked was slated to shut down at the end of August.

Amid this turmoil, in July, Jewish refugees began gathering around the consulate seeking transit visas through Japanese territory to escape the war in Europe. Japan’s policy at the time, based on its Immigration Law, was to deny such visas unless certain conditions were met: the applicants needed an entry permit issued by a destination country and sufficient funds to support their travel. Sugihara, though, seeing the plight of these refugees in the face of Soviet brutality, decided to issue the visas just the same, even when these conditions went unmet.

As Shiraishi describes, Sugihara’s visas were all written by hand at first. As he became caught up in the drive to grant as many permits as possible, though, he prepared stamps including one for his signature, enabling mass issuance. This stamp, notes Shiraishi, “was made by Poles who traced Sugihara’s signature. So here again we have evidence of Japanese-Polish collaboration.”

Another stamp bore evidence of Sugihara’s clever end-runs around limitations imposed by his Foreign Ministry superiors in Tokyo, stating: “This visa is issued based on the undertaking that an entry permit for the destination country will be obtained before the ship to Japan is boarded at Vladivostok and that bookings for the ship leaving Japan have been completed.” On August 16, 1940, he received the directive known as Telegram No. 22 from the ministry, ordering him “from then on” to strictly follow Japan’s visa-issuance rules—a phrase he took to mean the validity of the permits he had distributed so far. The clever diplomat continued issuing his visas until the closure of the Kaunas consulate, after which point he finally replied to this telegram.

Japanese border control officers, and the Japanese public, were increasingly surprised by the steady stream of desperate Jews disembarking at the port of Tsuruga, Fukui Prefecture. But Sugihara remained dedicated to saving as many as possible. As the author writes: “Sugihara firmly believed that giving these people a helping hand would prove beneficial to Japan in the future, and his actions indeed demonstrated outstanding foresight grounded in the keen grasp of international affairs that he had honed during his years as an intelligence officer.”

A Mission Continued in Prague

In Chapter 7, Shiraishi writes about a less-known portion of the diplomat’s life-saving work, which many think of as something that took place in Lithuania alone. In September 1940 Sugihara was transferred to what was then Czechoslovakia, where he served for less than half a year; as the author notes, “Perhaps because of the brevity of his posting there, very little research has been conducted on his time in Prague, but he continued to issue visas to Jewish refugees there as well.” Here, though, he was on territory controlled by Nazi Germany, meaning he was carrying out his activities in direct defiance of Japan’s ally.

A common image of Sugihara Chiune is of a hero who worked to rescue Jews from the Nazis. As Shiraishi makes clear, though, the bulk of those he saved were aiming to flee the Soviet menace in the Baltic states. It would not be until he arrived in Prague that Sugihara squared off against Adolf Hitler in addition to Joseph Stalin.

In 1941 Sugihara was assigned to a diplomatic outpost in the East Prussian city of Königsberg (today Kaliningrad, Russia). There he worked together with intelligence officers from the Polish government-in-exile to survey the area along the Soviet border—dangerous work that saw them frequently tailed by German agents.

In the course of these surveys Sugihara discovered armored German forces amassing in the forests. Going straight to work on analyzing this intelligence, he determined that Germany and the Soviet Union, despite the nonaggression pact they had signed in August 1939, would soon be at war with one another. He immediately fired off a telegram to Tokyo.

The Japanese authorities, though, ignored his warning, and were soon plunged into panic when the Germans invaded Russia, just as Sugihara’s report had insisted would happen. Germany grew wary of his presence, and at its ally’s behest, Japan soon transferred him to Bucharest, Romania, a remote location from where he could gather little further intelligence on German doings. He would spend the rest of the war there; after hostilities ceased, and he returned to Japan, he left the foreign service.

With this exploration of Sugihara Chiune’s career, Shiraishi Masaaki has produced a finely detailed overview of the reasons he was able to issue his “visas for life” and save so many thousands of refugees. The book is a worthy addition to the Japan Library collection put out by the Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, a project funded by the Japanese government to get more quality Japanese nonfiction works before the eyes of overseas readers. One hopes that Sugihara Chiune: The Duty and Humanity of an Intelligence Officer will cement a fuller, deeper picture of this humanitarian and dedicated intelligence officer in the global mind.

(Originally published in Japanese.)

Sugihara Chiune: The Duty and Humanity of an Intelligence Officer

By Shiraishi Masaaki

Translated by Gaynor Sekimori

Published by Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, March 2021

ISBN: 978-4-86658-174-3