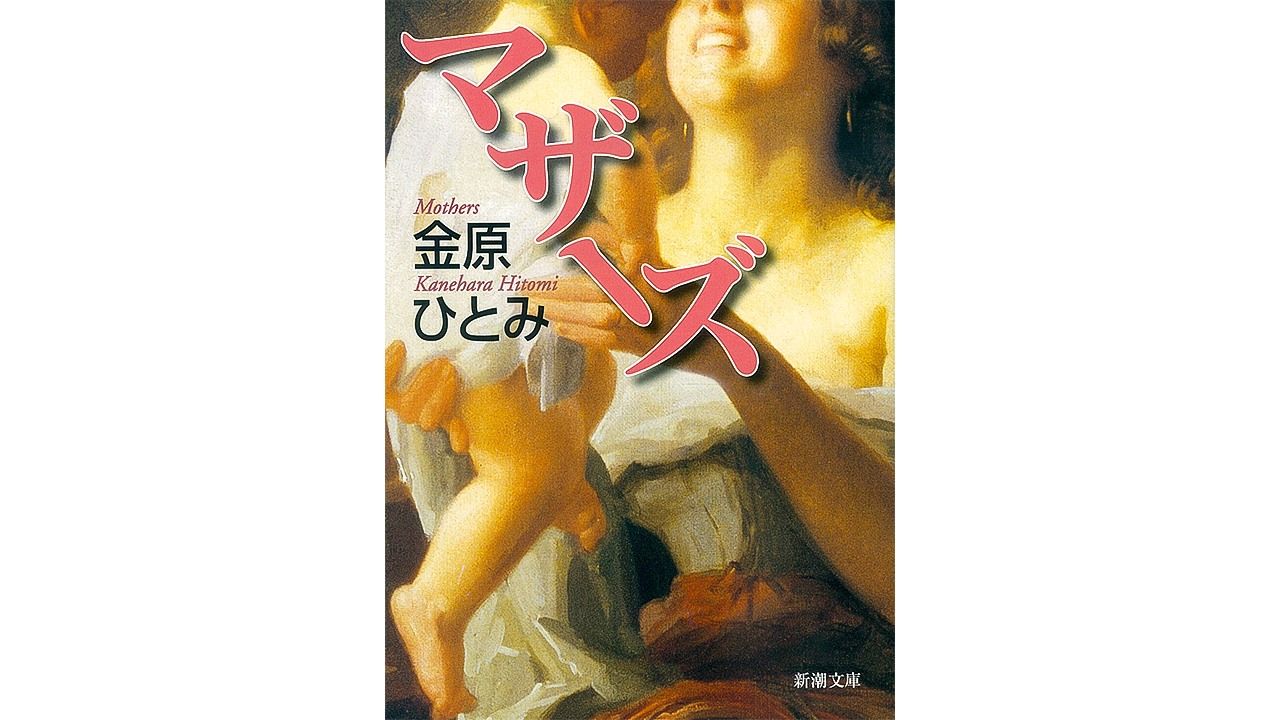

“Face Your True Feelings”: Kanehara Hitomi’s “Mothers”

Books Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s debate on how to arrest its declining birthrate is characterized by an endless procession of analyses, warnings, proposals, and policy measures. Yet, Japan isn’t making any progress. This is nothing new, of course, but it makes me wonder how serious people are about engaging with the problem.

What the problem boils down to, in short, is that the number of people who feel that they want to have a child is on the decline.

Kanehara Hitomi’s 2011 Mazāzu (Mothers) should be a go-to book for people who really want to understand the real reasons why Japanese women do not want children.

Torture Dressed up as Childcare?

Kanehara Hitomi first rose to prominence following the publication of Hebi ni piasu (2003) (trans. by David Karashima as Snakes and Earrings). This won her the 2004 Akutagawa Prize at the age of 20 and recognition as a rising star of Japanese literature.

The stimulus for her 2011 outing Mothers was Kanehara herself becoming a mother three years after her Akutagawa success. Mothers focuses on three women: the model Satsuki, the writer Yuka, and the housewife Ryōko. All three are young mothers with children at the same daycare facility who become friends. At first glance, on the surface, they seem like the “normal, cheerful mothers” that you see everywhere in Japan.

However, each one has her own secret.

Satsuki, for example, is having an affair; Yuka is on drugs; and Ryōko is dealing with uncontrollable anger toward her children. For a time, this all hangs in the balance until one day a single thread breaks, setting into motion a tumultuous set of events that upends all their lives.

Some readers might dismiss the events in Mothers as farfetched or unrepresentative of reality. However, such people probably have never known the true trials of childcare or the painful feeling of being pushed to the edge.

The author herself had to endure a difficult time when she first became a mother. In addition to suffering from postpartum depression, Kanehara had to move around following the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, eventually moving to France. There she raised two children by herself for 18 months before her husband joined her. Mothers pulls no punches when it comes to describing the negative aspects of parenting. It does not hesitate to explore the “true feelings” that many mothers often have.

As such, the book contains various confronting lines:

“This is torture in the name of child rearing.”

“Just for a day, or even a few hours, I want to get away from my everyday life. I want to take a break from seeing the world as a mother.”

“Sometimes I just want a minute away, or to even get a meter away from my child.”

“But if I say things like that, people will see me as some kind of heartless, demon mother.”

“I just want people to sympathize with me and understand what I am going through—not just help, but recognition.”

I am sure the words of Satsuki, Yuka, and Ryōko in the book have all passed through the minds of many mothers. Perhaps they are consciously or unconsciously suppressed given the prevailing social attitude that “a mother who loves her children would not think things like this”.

Of course, the events of the novel are dramatic and not common to everyone’s experience of motherhood: adultery, abortion, abuse, drugs, neglect of children.

But how many mothers can assure themselves that, if they were faced with different circumstances, they would not turn out like Satsuki, Yuka, or Ryōko?

At least I can’t. My experience of motherhood could well have turned out like any of the three women, depending on the circumstances.

Similarly, what if a few things were a little different for the women in Mothers? If their extended families were closer, or their children slept a little better, if they could get into kindergarten or daycare more smoothly, if they could share their frustrations more freely with friends or if their husbands were around and more proactive toward childcare? These women may not have gone over the edge and made their way through the tumultuous times depicted in the novel. The lives of mothers are more fragile than people realize.

“Inhuman Lifestyles”

Mothers was published in 2013, but the book still gnaws at the hearts of mothers more than a decade later. After all, very little has fundamentally changed in the plight of the Japanese mother, making the book as relevant as ever.

More than 10 years after the publication of Mothers, Kanehara wrote an essay for the November 15, 2023, Asahi Shimbun. Titled “To Those Struggling with Wearing the Mask of a Mother,” Kanehara writes that “my children are cute, and I have no regrets, but from a certain point of view I feel that mothers live ‘inhuman lifestyles’ and are put through too much.”

If there have been any changes since the publication of Mothers, it is probably the result of the spread of social networking services and the ability for people to access information from anywhere. Social media has become a major source of information for the current generation of new mothers, as well as a place where they can share the joys and pleasures of child raising as well as the sorrows, complaints, and frustrations that come with these “inhuman lifestyles.”

The prevailing sense that women should “just put up with it” and suffer in silence is slowly being fractured. People are realizing that there is nothing good about unnecessary suffering. Mothers are now free to scream out, “being a mother can be so painful!” This act, made possible by the protection of the anonymity of online expression, might help reduce the isolation of being a mother. Not having to suffer alone may in turn help relieve the tensions, building up in the body and the mind, that were previously suppressed.

On the other hand, the accessibility of social media also means that even younger generations of women are being exposed to graphic accounts of the pain of being a parent. We should not be surprised, therefore, that they are anxious and hesitant about giving birth and raising children—purportedly, about half of Generation Z do not want to have children in the future.

Japan’s birthrate may fall even further in the future. If the government really wants to get serious about addressing this problem, it will have to engage with the negative emotions and feelings that come with being a parent and go beyond proposing superficial measures.

A Novel With a Social Message

Snakes and Earrings, which won Kanehara the Akutagawa Prize in 2004, also focused on a topic that would have at the time been uncomfortable for many Japanese to contemplate: body modification. The novel placed the body modification subculture at the center with its focus on full body tattooing, piercings, and tongue splitting (which makes people look like they have the tongue of a snake). Kanehara has always faced challenging, graphic, and edgy topics which force her to be straight with herself about her own feelings.

Rather than analyzing societal defects or making explicit social commentary, Kanehara always reflects upon how she feels and how that influences she sees society and engages with current events of that time. She does not shy away from exploring her own raw feelings.

For example, in her 2004 Asshu beibi (Ash Baby), she faces homosexuality and pedophilia; in the 2015 Motazarumono (The Have Nots) she explores the aftermath of the earthquake and nuclear accident; in Atarakushia (Ataraxia, 2019), Kanehara reflects on married life; and in Ansōsharu disutansu (Unsocial Distance, 2021), she covers the social isolation experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While her works tend to appear in the form of novels, there is nevertheless usually some kind of social message in the background. Rereading Mothers in 2023 brings me a sense of amazement about how contemporary it still feels more than a decade on. Then, as now, society was obsessing over the declining birthrate problem. Kanehara’s confronting contribution to the debate still carries major weight today.

(Originally published in Japanese.)