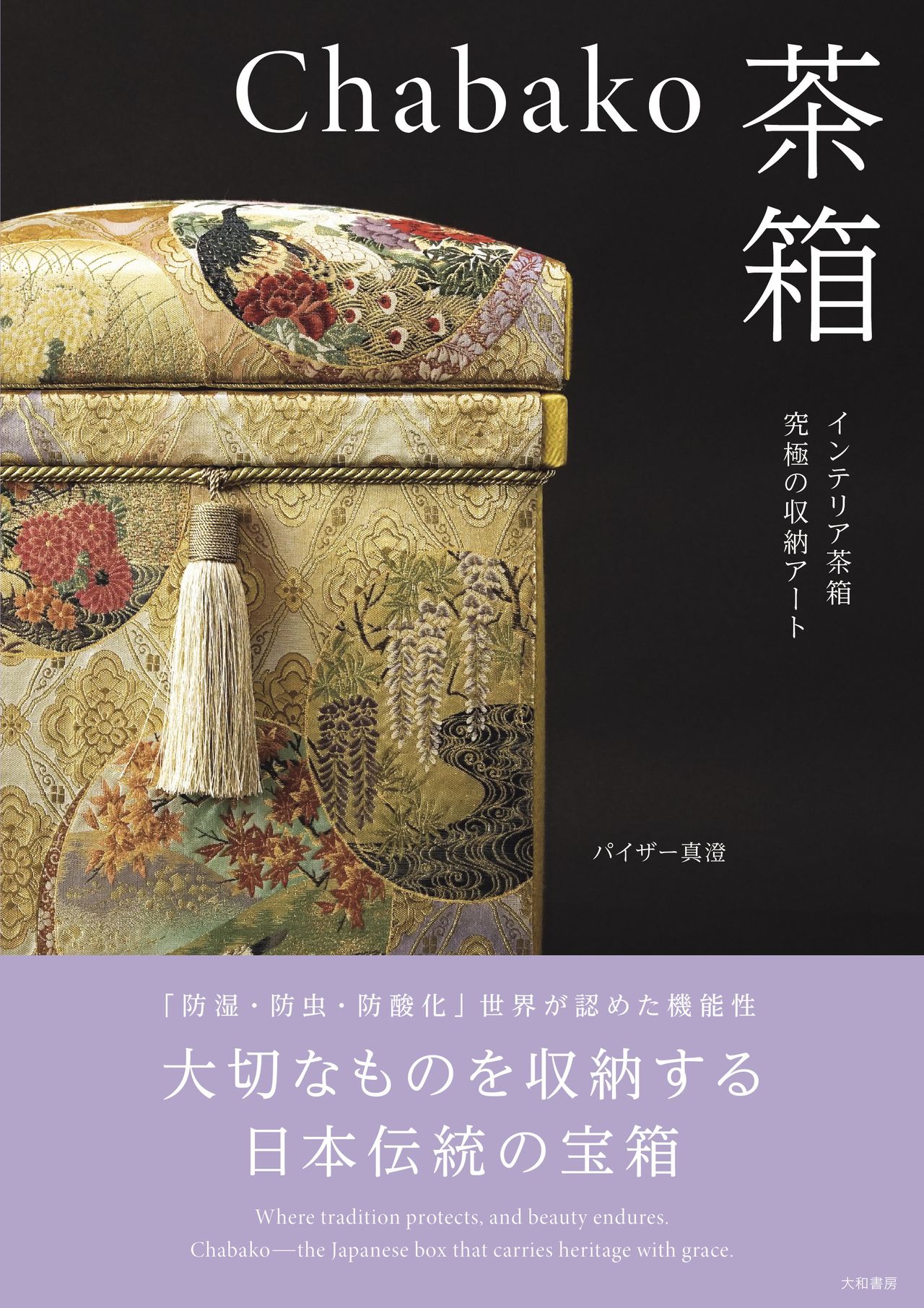

Form Following Function: Japanese Tea Boxes as Interior Decoration

Books Art Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Colorful Twist on Tradition

In mid-October 2025, an event was held to launch a new book—Chabako (The Tea Box), by Masumi Pizer—at a gallery in Kyōbashi in central Tokyo. The Interior Chabako Club, led by Pizer and based in Tokyo’s Shinagawa, used the occasion to show off a variety of its stylish “interior tea boxes,” including a number of new pieces.

Masumi Pizer with a selection of chabako at the launch event for her new book on October 17, 2025, in Kyōbashi, Tokyo. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

The term Interior Chabako is a registered trademark belonging to the club. Chabako were originally tea chests used for storing and transporting tea leaves. The interior versions are an adaptation of these chests for modern use. The chests are wrapped in kimono or obi fabrics, woven fabrics from other parts of the world, and cushion materials, transforming them into decorative items for use in the home. As the book describes them, large chabako can be fitted with casters or wooden legs to become stools or benches, or topped with an acrylic sheet for use as tables or display surfaces. With creative ideas adapted to your lifestyle, chabako make the perfect interior pieces for any room.

Roots in Japan’s Expat Community

Chabako come in more than 20 different sizes, from large chests that can be used as furniture to smaller pieces ideal for use as table-top storage boxes. The concept originated in “fabric-covered chabako” created by foreign residents living in Japan, who wrapped the boxes in favorite fabrics and modified them for use as decorative and functional storage chests.

Pizer fell in love with fabric-covered chabako when she encountered them among Tokyo’s expat community in 1998. The following year, she started classes on decorative chabako, and in 2004, she founded the Interior Chabako Club as a limited company. In 2005 she began offering certified instructor courses. Today, the club has 125 classrooms around the country, with instructors in the United States and Germany.

The original fabric-covered chabako, made by foreigners with close connections to Japan, mostly used traditional Japanese fabrics intended for use in kimonos and obis. It is fair to say that interior chabako take the concept a step further, incorporating the standard Nishijin-ori and Yūzen options along with a variety of traditional fabrics from France, Italy, and beyond. Today, they are attracting growing interest overseas as practical and appealing works of art that can bring colorful accents to interiors.

The World’s Most Durable Storage Chests?

The book also touches on the history of the chabako themselves. The first export of Japanese tea is believed to date back to 1610, when the Dutch East India Company took a transport from Hirado, Nagasaki to Europe. But without durable tea chests, capable of keeping tea leaves fresh and transporting them safely across long and difficult voyages, it is likely that green tea would never have become established throughout Japan and the wider world.

The first chabako date to the Edo period (1603–1868). It was in the early Meiji period (1868–1912) that they reached their present form of a cedar box lined with tin. These modern chests offered vastly improved protection against moisture and insects. Skilled craftsmen produced boxes that were strong enough to last a century or more. By the late nineteenth century, chabako were being exported as desirable products in their own right.

Over time, however, cheap and convenient materials like cardboard and aluminum bags became popular as alternatives for transporting and storing tea, and threatened to make chabako obsolete. Demand plummeted and businesses struggled to find successors as the young generation looked for work elsewhere. One after another, specialist chabako makers closed down, until in 2024, just three remained.

Preserving the Craft for the Next Generation

The book rightly describes chabako, with their more than 150 years of history, as the crystallization of a number of different Japanese craft skills.

The cedar used for the outer frame is generally at least 30 years old. After being exposed to the elements for at least three months, the wood is weighted and dried thoroughly to prevent warping and distortion. Galvanized tin sheets are used for the lining, while corners, joins, and other areas vulnerable to damage are reinforced with thick strips of washi paper. All the materials used in the boxes are painstakingly produced by experienced craftsmen.

A look at the process of chabako creation by artisans in Kawane. (Courtesy Interior Chabako Club)

The Interior Chabako Club has worked hard to preserve these endangered skills and pass them on to the next generation. This book tells the story of this battle to save valuable traditions for the future.

Shizuoka Prefecture, one of Japan’s top tea regions alongside Uji (Kyoto and surrounding areas) and Sayama (Saitama), is home to Kawane Honchō, known for its famous tea. The club partnered with Maeda Seikanjo, a long-established maker of high-quality chabako, to preserve the craft. In 2010, they submitted a petition to the town’s mayor to keep the small industry of chabako alive and began training young craftspeople to carry the tradition into the future. Maeda Kōbō was established with local government support in 2016, and the company started operations from a new factory in 2020.

A Deluxe Bilingual, Full-Color Book

Pizer’s book features richly colorful photographs showing a diverse selection of interior chabako in all their glory. Many are collaborations with prominent designers and brands, both Japanese and international. The full-size photographic spreads give the book a striking visual impact and make it a joy to look at.

The book also contains seven engaging and informative columns examining the boxes and the culture that has grown up around them, including “Starting a Legacy,” “A Tradition to Enjoy,” and “The Prayer of Pope Francis.”

The author spent her childhood living with her family in London. She later worked for Mitsubishi Corporation and Citibank NA in Tokyo. This book reflects more than 25 years of her passion for chabako and is presented in both Japanese and English text.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Daiwa Shobō.)