Sharing the Real China: A Personal View on Mutual Understanding

Global Exchange World Culture Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Experiencing the China Miracle

To me, Japan feels like my motherland, but China seems like my hometown. My early childhood memories are of walking through the streets of Beijing in winter holding a bingtanghulu (a traditional snack of candied hawberry on a bamboo skewer). Nineteen years living in Beijing turned this Tokyo tot into a bona fide Beijinger.

In summer 2000, aged 5, I moved to Beijing with my parents, whose work took them there. I had imagined China as a flat, expansive country, epitomized by Tiananmen Square, which I knew from television, and people rushing about their daily lives by bicycle. I recall my surprise at finding that it was actually not so different from Tokyo. Looking out of the windows of our home and seeing the high-rise buildings and elevated highways, I saw that Beijing was a metropolis.

In 2001, the year after we moved, Beijing was chosen to host the 2008 Summer Olympic Games, and China gained admission to the World Trade Organization. This marked the start of a miraculous economic growth phase for the country, bringing even greater changes to its capital’s cityscape. The nation was particularly invigorated following the Olympics, with further acceleration in economic growth—as it steadily realized its place as a member of the global community. For someone of my generation, born after the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble, it was a valuable experience.

The longer I stayed in Beijing, the more accustomed I grew to living there, until I considered myself a true Beijinger. I loved luzhu huoshao, a traditional street food made with pork, offal, and tofu, served with bread, and beibingyang, a carbonated drink popular with all age groups. I also acquired a typical Beijing accent, characterized by rhotacization, a heavy r-sound made by rolling the tongue.

In summer, I often meandered through Nanluoguxiang, an old-fashioned hutong (alleyway) in Beijing’s Dongcheng district, while enjoying dahongguo (an ice treat made with hawberry). In winter, I loved to go skating at the natural ice-covered lake in Houhai, part of the city’s Xicheng district. Before I knew it, I adored Beijing, and indeed China as whole.

Realizing I Was a Foreigner

Soon, I had spent more of my life in Beijing than in Japan. But of course, from time to time, I was forced to confront my foreignness—although I spoke the local language, there was no escaping prejudice and discrimination.

One day in high school, I was shopping with a friend, speaking Japanese, when a shopkeeper called us Riben guizi (Japanese devils, a well-known derogatory term) as we walked by. Perhaps the shopkeeper did not harbor ill intentions, but it was still hurtful—both of us had lived in Beijing for many years. In contrast, when I returned to Japan, although I was “just another student,” I was personally subjected to criticism and discrimination aimed at China.

At that time, rather than attempt to find a solution, I chose to avoid such situations. I would give vague responses to questions concerning the subtleties of identity. Both countries hold great significance and sentimental value to me. Even after I started university, I spent each day fretting over the question of where I came from and where I was headed.

Looking back on it now, I realize that my doubts were meaningless. In modern society, identity is a commodity—what is important is how we perceive such things as we go about our daily lives.

A Mission to Communicate the Real China

After I entered graduate school, I became less concerned with identity. At the same time, I made an important decision for myself—to become involved in China-Japan exchange projects. By taking action, rather than agonizing, I realized that could steer matters in the direction of my ideals. I recognized the value of sharing the reality of China in writing, and, more importantly, of encouraging Japanese people to visit China and experience it themselves, to assist mutual understanding.

Japan and China are continuing to strengthen economic ties, and have become indispensable to one another, yet they are unable to completely overcome the historical and psychological issues that divide them. Despite being closely related both geographically and culturally, they remain distant.

In China, you see the latest technology everywhere, and cashless payment is so widespread that the people hardly require wallets. Zhongguancun and the city of Shenzhen, adjacent to Hong Kong, are key hubs for the ongoing development of new ideas and technologies. Beijing’s environment is also improving, with blue skies returning. Anti-Japanese sentiment is not the sole perspective—many Chinese people have developed an affection for Japan and its culture after traveling here.

I wonder how many Japanese people are familiar with the real China. During China’s period of reform and liberalization, the people who worked for the normalization of relations between Japan and China retreated from the front lines. I believe that it is my generation who are tasked with the mission of building the new era of Sino-Japanese relations.

The author’s graduation from Tsinghua University postgraduate studies (third from the right).

The Visit China Summer Program for High School Students

In 2018, while still a post-graduate student, I established Dot Station with my friends Itō Makoto and Arimitsu Hayato. This summer program takes Japanese high school students to China to experience the nation’s modern reality. By inviting students to China, the program aims to encourage them to view the country without prejudice, and provides an opportunity for them to expand their skills. “Dot” signifies the joining of the dots of the individual students, while the program hopes to be the departure “Station” for their experience.

To date, we have run the program twice, in 2018 and 2019, and 23 high school students have taken part. Many of them had previously studied in the United States, Canada, or Britain, and they were curious to see China, on track to become the global economic leader, with their own eyes. Some of the students also decided to attend university in China as a result of the program.

The visit focuses on providing realistic experiences of Chinese technology, entrepreneurship, and policy—aspects generally neglected by the Japanese media. We contacted the research institutes at our alma mater, Tsinghua University, and other organizations, to arrange a tailor-made program, according to the interests of the participants.

Our group toured the headquarters of ByteDance—operator of the video-sharing platform TikTok, and the world’s biggest so-called unicorn, or privately held startup valued at over $1 billion—and met with various entrepreneurs. We also visited the Japanese Embassy in China to listen to active diplomats speaking about Sino-Japanese relations from their vantage point in the country, as opposed to the perspective from back home.

Prior to traveling, many participants held a negative image of China, having been fed stories of air pollution and food production scandals by the Japanese media. Through our program, they experienced another, unfamiliar side of China, providing a very different impression of the country.

We established and structured the program from the perspective of students, and promoted it and made appointments with businesses on this basis. We even used crowdfunding to help sponsor the program. Fortunately, we gained support from many who empathized with our enthusiasm to deepen mutual understanding between the neighboring countries. More than anything, the greatest returns from this weeklong opportunity came in the form of participants seeing China with their own eyes and growing through their various experiences.

The high school students who joined the first program in 2018 have since entered university, and some are assisting Dot Station’s operations for the third round in 2020. It is satisfying to see the hopes of the program’s three founders being perpetuated by the students.

Working in Tokyo with Fond Memories of China

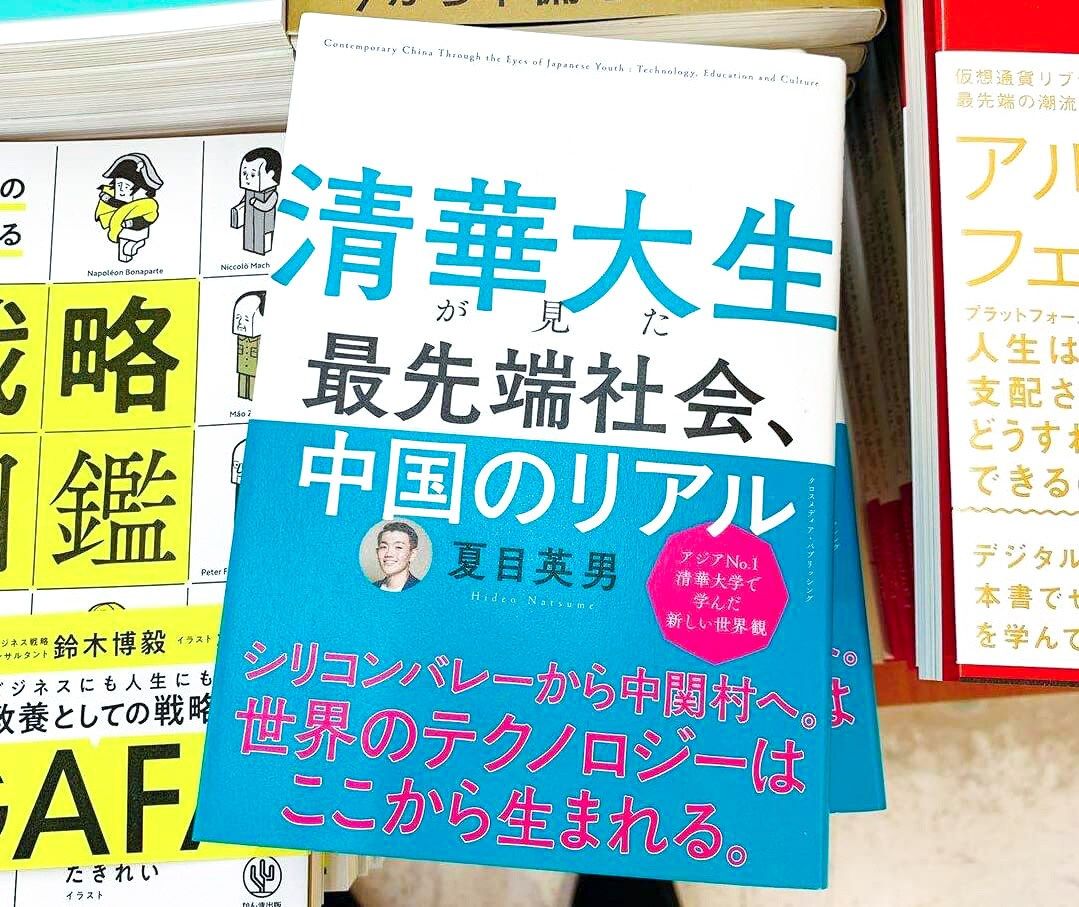

Starting in spring 2019, just before I graduated, I wrote a series of articles for the Japanese magazine Nikkei X Trend about trends among Chinese youth and the latest business information. Consequently, I was also asked to write a book. The result was published in March 2020: Seika daisei ga mita saisentan shakai, Chūgoku no riaru (The Real China: A Tsinghua University Student’s View of This Cutting-edge Society) The book depicts modern Chinese development from the perspective of a Japanese student, with a focus on the Chinese youth who will lead their country in the future. I wrote the book to help Japanese young people to gain a better understanding of the current reality of China, whereby they can reassess their assumptions and discover new options.

Natsume’s book, published in March 2020. It discusses aspects of China today that go largely unreported in the Japanese media.

The message I most wanted to share is that Japan and China can grow together by cooperating and collaborating, rather than competing.

I returned to Japan after graduating in July 2019, and now work for a Japanese governmental agency on projects linking Japan and China. Despite this, I still have strong nostalgia for my “hometown” on the continent. Southern Liang dynasty poet He Xun wrote: “When spring comes to the capital, guests yearn for their hometown.” As I walk the tree-lined streets of Tokyo, I recite the Chinese poem, “Spring comes, and amid the falling cherry petals, the faint smell of peonies, I recall my hometown.”

Natsume has been working since October 2019 at a Japanese governmental agency, where his tasks include interpreting for important guests from China.

(Translated from Japanese. Originally published on the Japan Science and Technology Agency’s website Kyakkan Nippon (Japan Objectively), created for a Chinese readership. Banner photo: High school students visiting Tsinghua University on the 2018 Dot Station summer program. The author is standing behind the group, arms raised. Photos provided by the author.)