Legends: Japan’s Most Notable Names

Gomi Tarō: The “Everyone Poops” Author Looks Back on a Life in Picture Books

People Culture Arts Family Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Picture Book Landscape

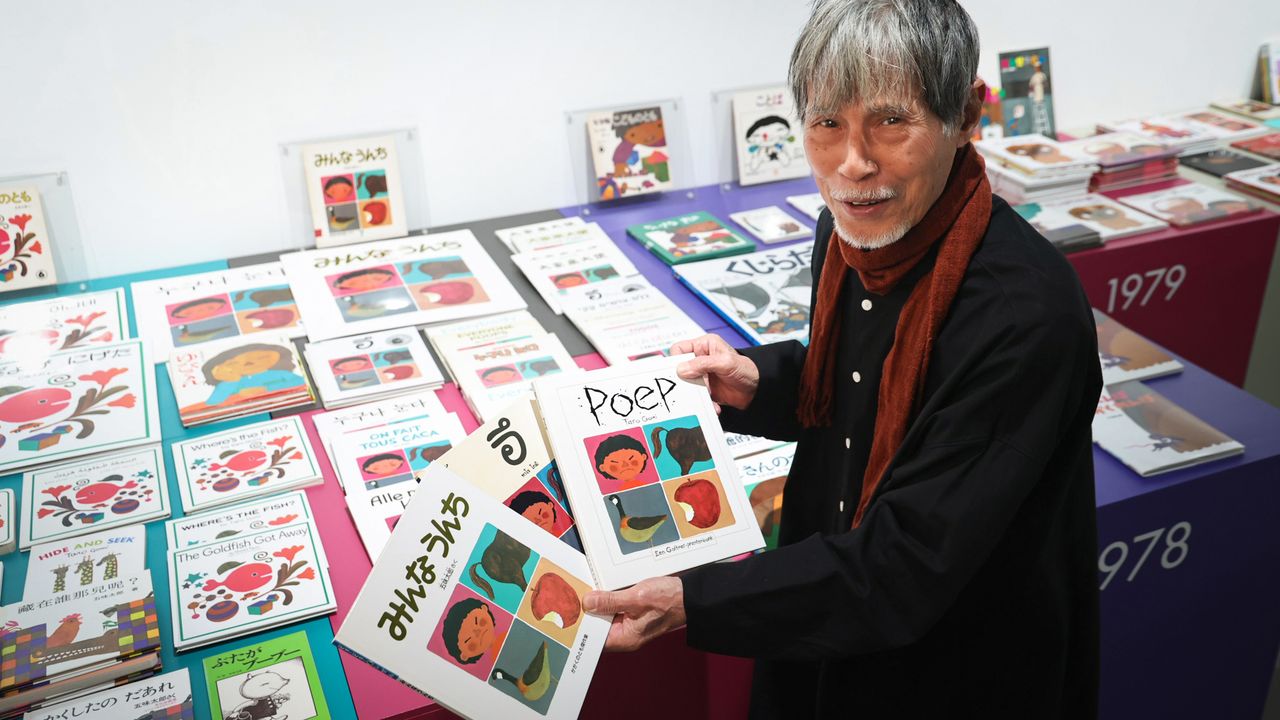

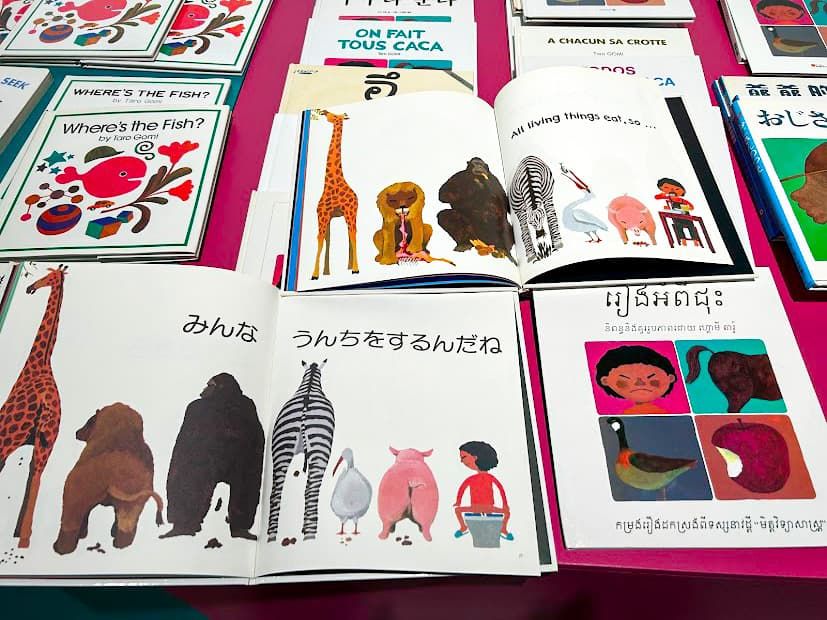

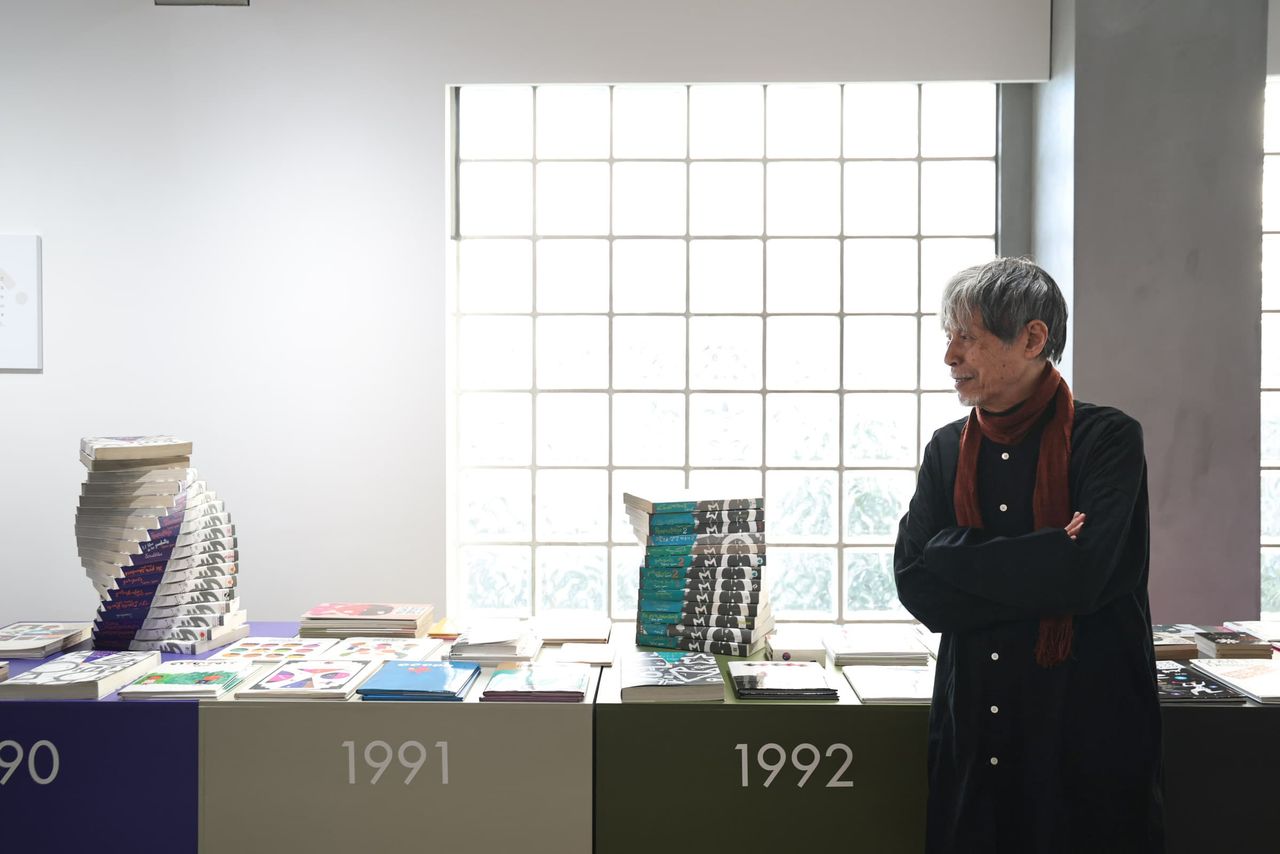

An exhibition at Tokyo’s Lurf Gallery running through February 15, 2026, assembles works by picture book author Gomi Tarō spanning more than half a century from his 1973 debut until 2025. As well as all 372 Japanese originals, there are translated editions published in more than 30 countries. Displays of popular books like Everyone Poops with titles in a variety of languages convey the global appeal of Gomi’s world.

“Even if I try to grasp the range of my picture books in my head, I don’t have a concrete idea of their scope. I wanted to physically line them up one time to see what kind of landscape they formed,” Gomi says. “To see what kind of changes there were over fifty years. But I actually had a strong feeling of how consistent I was, and that I hadn’t changed.”

Visitors can pick up and read the books on display at the exhibition. The first translation of a Gomi picture book was Coco Can’t Wait, which was published in the United States in 1979 (later published under the title I Really Want to See You, Grandma) (center of photo at left); The Goldfish Got Away and Everyone Poops, visible in the collection at right, have appeared in a number of languages. (© Hanai Tomoko)

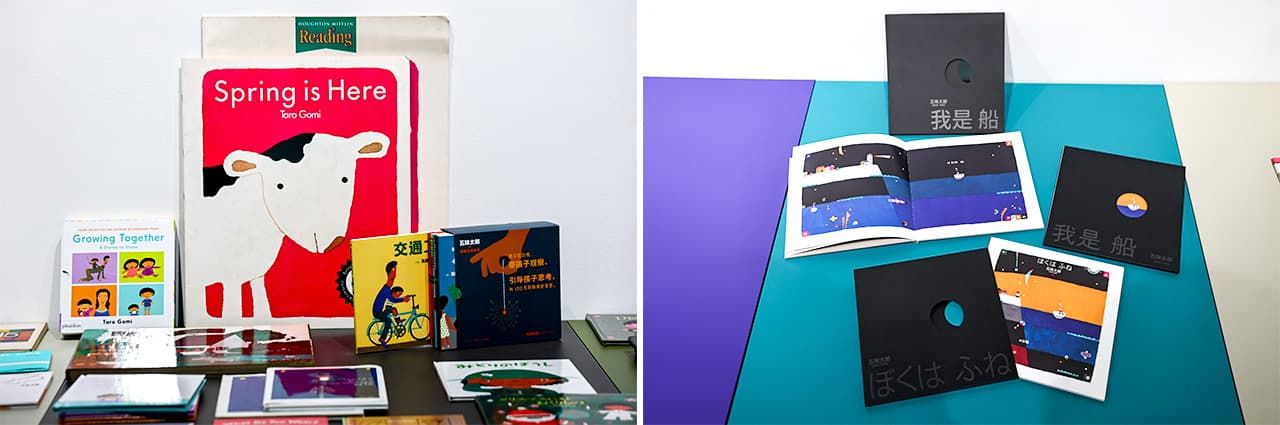

Spring Is Here (left) won the Bologna Children’s Book Fair Award in 1981; I Am a Ship (right), written when Gomi was 79, shares his various emotions in 50 years of creating picture books through the story of a ship that sails onward while being asked “Where have you come from?” and “Where are you going?” There are Chinese translations, but as yet it has not been translated into English. (© Hanai Tomoko)

A Questioning Stance

Gomi once had jobs in industrial design and advertising, but he felt constrained by considerations of “users” and “clients.” Since discovering the enjoyment of creating picture books, he has said, he no longer has the sense that he is working; he never feels that he is writing for children in particular.

“What are books for children anyway?” Gomi asks. “Children’s books tend toward this attitude of trying to get kids to appreciate adult values, like manners, a moral outlook, and order. With me, there’s always a questioning stance: ‘I’ve made this picture book, and I wonder if there’s anyone with the same kinds of tastes as me.’ Many children have responded to this—including some in other countries.”

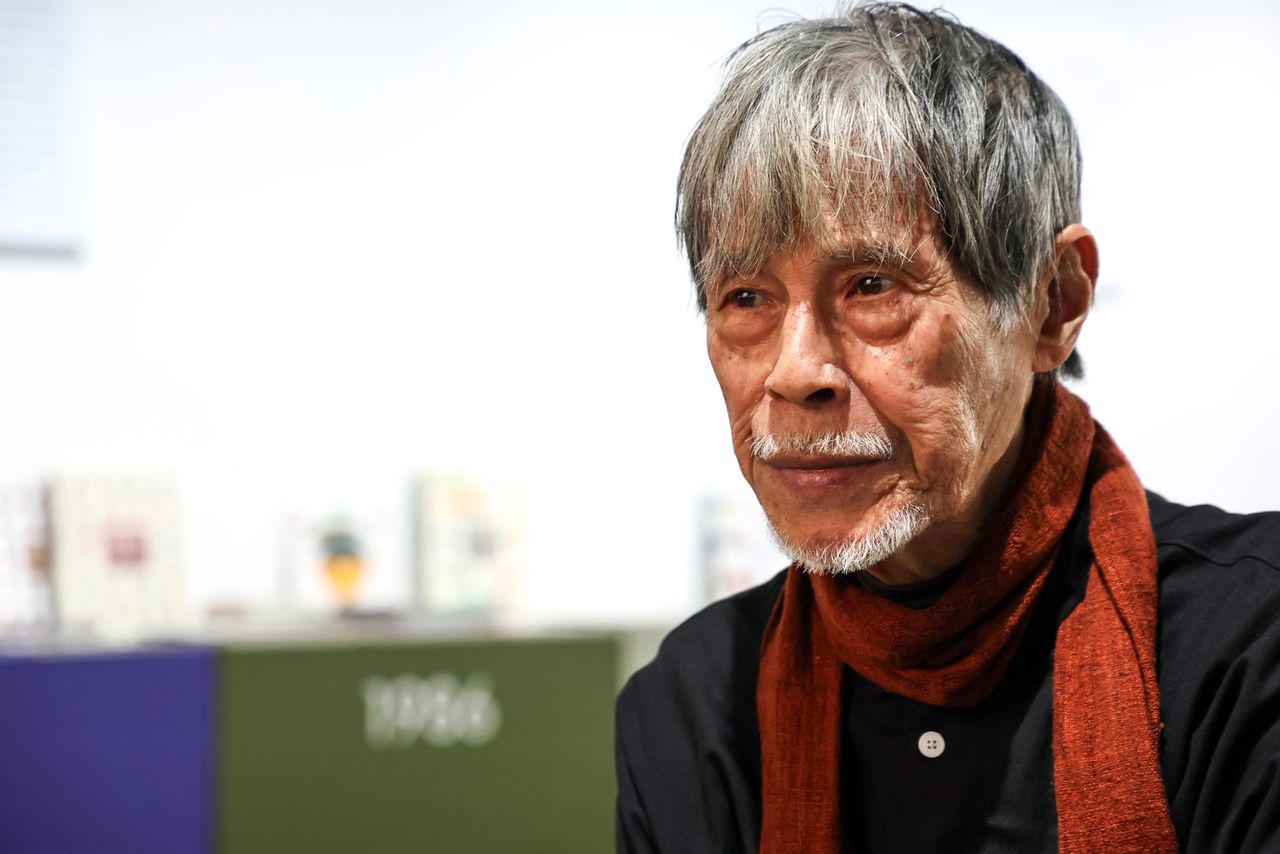

Gomi Tarō says his picture books are not particularly aimed at children. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Gomi reflects, “Kids don’t read because adults tell them to, they read because they want to. Books are something that people discover on their own. If you start out with the idea of targeting kids, it becomes artificial. And there are always adults between the children and the book—reading to them, and so on. Right from the beginning, I didn’t want to do it that way. And I had some huge battles with editors when I was starting out.

“These days, there are no more battles. It’s almost boring, in a way. But seeing my books laid out, I sense the history, and I’m proud of how I changed the way picture books are thought of in Japan.”

Everyone Loves Poop

Since the 1977 publication of his Everyone Poops, Gomi has received letters from his young readers.

“I think children love poop as much as they love certain foods or toys. But there was a culture among adults that it shouldn’t be talked about directly. Seeing some old guy drawing poop must have made the kids’ day. I got loads of letters saying ‘I look at poop too’ or talking about their ‘poop diary.’”

Everyone Poops struck a chord with many. (© Hanai Tomoko)

The book was not based on a strategy to appeal to children, he explains. “I happened to have a meeting with the head of Tokyo’s Tama Zoo. He’d asked me to get there early in the morning before the place was open, as he was busy, so around six I came in the back gate and strolled across the zoo to his office. Just then, the morning sun struck some animal droppings with steam rising from them, and I thought it was a beautiful sight. I took a lot of pictures.

“On the way back, I had the idea to draw a book about poop. There were books about food, but none with vivid pictures of the end product, after it had passed through the body and come out again. People only see the zoo after it’s been cleaned up. I’d been lucky. Then, when I’d started sketching and shown some quite interesting pictures to the publishers, they’d asked me, ‘You want to do a book about poop?!’ and they weren’t at all keen on the idea.”

But when it was published, children were quick to respond. Also, one day, a middle-aged foreign woman Gomi had never seen before suddenly came to visit. She was a French editor who had come to tell him directly that she wanted to publish a translation of Everyone Poops. She could not understand Japanese, but apparently had fallen in love with the book after seeing the pictures. Gomi says it was the first time he realized, “There are people with the same tastes as me in other countries too!” A French translation was published in 1989, and there are currently translated versions in 18 languages.

Gomi’s charming illustration shows everyone lined up doing a poop. (© Nippon.com)

With publication overseas, Gomi now receives letters from children in other countries. “Everyone Poops might be a little special, but when people read my picture books, it seems they all want to talk about them.” There are also children who send their own pictures and wordplay. “My book has a big part in how they’re all playing,” Gomi says with satisfaction.

Making Friends

Gomi now receives email from readers and fans around the world. “They say things like ‘I love your books. I want you.’ When I check, these people might be from a publisher in Azerbaijan or South Africa. I have a copyright agent to deal with translation offers. There are also requests for online interviews. I’m grateful, but at the same time, they’re a bit of a hassle.”

He leaves translation to the individual’s judgement. “I aim to write pithy sentences, which come together as part of the picture book. How translators interpret them and put them in their own words is a constant issue in translation. But I’m confident that my books remain essentially the same, even if the words change.”

Gomi also has books that are not only for reading. His books Scribbles (1990) and Doodles (1992) include partly drawn pictures for readers to complete. These have appeared in 18 languages, and Gomi has led workshops in a lot of different places.

“If you do a workshop overseas, you get friendly with the children straight away. We’ll greet each other, ‘Hey!’ from the first meeting. They’re all excited, doing what they want. It’s easy to make friends, never mind the language gap.”

Versions of Scribbles from different countries are exhibited in a spiral-shaped pile. (© Hanai Tomoko)

When he was young, Gomi made solo trips, traveling to various places, but now he mainly only heads out for events like overseas book fairs and workshops. He has visited almost all of the countries in Europe and Latin America, and has also been to China and Africa.

When he goes to another country and browses at a bookshop, he sometimes finds his own books. “I’ll think to myself, ’I’ve seen that book somewhere before. That’s right, I wrote it!’ Of course, I’m happy to have these kinds of encounters.”

“Perhaps I’m Addicted”

Born in 1945, just after the end of World War II, Gomi played outside a lot when he was young. Back then, there were still rice paddies and open fields in Tokyo, and he would play with spinning tops or come up with games to enjoy with refuse found on the ground, like “kick the can.” He also enjoyed digging holes—not just in vacant lots, but in the garden and schoolyard too.

Gomi has compared making picture books to digging holes. “Let’s curve it here, or dig deeper. It’s fun digging holes . . . I can dig good holes.”

He goes on, “I don’t have a methodology. It’s just been a life of constantly collecting ideas for picture books, here and there. There are so many interesting topics, and the most exciting part for me is the moment I sense I can express a particular feeling or impression as a picture on the page, or in three dimensions.”

“There are so many interesting topics.” (© Hanai Tomoko)

It is more about wanting to make books than to draw pictures for Gomi. “I don’t know if making books is work or play,” he says. As soon as he finishes one book, he wants to start the next one.

“I like the form of books. You can write anything you like, and you can punch holes in them or cut them too. I’m at my most relaxed when I’m making a book. Perhaps I’m addicted. But books are a platform for including all kinds of ideas—the possibilities are endless.”

Picture Books by Gomi Tarō Mentioned in the Article

- Everyone Poops, translated by Amanda Mayer Stinchecum from Mina unchi

- I Really Want to See You, Grandma, translated from Hayaku aitai na

- The Goldfish Got Away, translated by Robert Campbell from Kingyo ga nigeta

- Spring Is Here, translated from Koushi no haru

- Boku wa fune (I Am a Ship) (no English translation)

- Scribbles: A Really Giant Drawing and Coloring Book, translated from Rakugaki ehon

- Doodles: A Really Giant Coloring and Doodling Book, translated from Rakugaki ehon 2

Note that some books have appeared in English with different titles or in different versions, but only one version is given in this list. Translators mentioned only when known.

(Originally written by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com and published in Japanese. Banner photo: Gomi Tarō holds translated versions of his picture book Everyone Poops at Lurf Gallery in Tokyo in December 2025. © Hanai Tomoko.)