A Japanese Psychiatrist’s Takes on the Trials of Life

Coming to Terms with “Invisible” Issues in a Time of Enforced Self-Reflection

Society Health Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

COVID-19 has the world quaking, and because it is an invisible threat, the terror it has struck in our hearts shows no sign of abating.

Up to now, humanity has achieved prosperity and progress at an accelerating pace through an ongoing process of discarding the invisible in favor of the visible. Drunk with this success, we have taken to slighting that which cannot be seen and endlessly pursuing that which can. But now we find ourselves forced to directly confront the invisible in the form of the threat that has suddenly bared its fangs against our species.

Dismissal of Existential Troubles

In my field, mental health care, there has been a trend, particularly in recent years of emphasizing only the visible adaptive behavioral aspects of encouraging long-term absentees from school and the workforce to return to society. I cannot deny the need for this kind of support. At the same time, I cannot overlook the fact that even when a client brings up an issue like the invisible existential distress of not knowing the meaning of one’s life, it is all too common for mental health care practitioners to adopt the same emphasis, offering no more than encouragement of renewed social participation.

In almost all cases, practitioners make a by-the-book, perfunctory diagnosis—commonly labeling the client’s condition as depression—and merely offer the usual antidepressants and guidance about recuperation. To clients agonizing about their purpose and why they should go to work or school, they just make arbitrary statements like “You’re only thinking like that because you’re depressed” without addressing the questions themselves.

Once, when I appeared on a talk show, I said, “I believe it might be necessary to deal directly with the existential emptiness of people today.” To this, another psychiatrist responded mockingly that he thought there were almost no patients seeking deep consideration of existential matters. Supposing that I may have fallen into anachronistic thinking, at the time I made a self-deprecatory comment to conclude the exchange. But upon reconsideration in the face of our present situation, I now strongly feel that invisible, existential issues are fundamental for people as spiritual beings and should not be belittled.

Increase in Suicides

National Police Agency figures show that, after steady decline from 2009, the number of suicides has been increasing since July 2020. According to statistics from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan has the highest suicide rate among the Group of Seven major advanced economies, and it is the only country in which suicide is the leading cause of death for young people aged 15 to 39.

I think visible economic factors like the downturn in the job market and the business slump are significant factors contributing to the high suicide rate. There are likely also many cases, however, where people whose movements are curtailed have lost sight of their reason for living and become overwhelmed by invisible, existential issues. As the pandemic rages and people are asked to stay home, those who had placed weight on an active life outside the home have been deprived of their usual social and recreational opportunities. As a result, they have been forced to face up to their own selves.

To be sure, people have been making more active use of online channels for communication and entertainment, and these may seem to offer convenient substitutes for what we are lacking. Yet, as a stay-home lifestyle stretches into the longer term, we actually feel a qualitative dissatisfaction arising from the fact that the substitutes are nothing more than substitutes. A great longing is building up within us for face-to-face communication and real-life emotional experiences.

In any case, this unusual shut-in situation requires everyone, like it or not, to enter a stage of introspection and self-reflection.

There have been a number of shocking reports of suicides by popular celebrities who seemed to have everything going for them. They are notable in that there were no financial issues or other problems as visible factors that society might normally see as the reason for these people’s deaths. This seems symbolic of the truth that conspicuous worldly or financial success alone cannot sustain our lives as human beings.

Lives Lacking Depth

We live in an age of convenience. We can easily get hold of any data we may need, along with manuals providing instructions for various tasks. But the easier it becomes to do things, the more we lose a sense of depth. Processes are bypassed and there is a growing tendency for people to desire only quick results. Considering such “useless” invisible matters as why we live is dismissed with disdain and viewed as overthinking or a sign of depression.

The arts and literature used to play important roles in providing hints on existential matters and helping people feel purpose in their lives. But now, in the continual quest for marketing success, they all too often lapse into mere entertainment. People may pursue fields like art and philosophy as a route to joining the business elite or as mere sources of facts for answering questions on quiz programs.

Thus, our lives now have become deficient and lacking in depth, as we are entirely surrounded by diversions promising instant relief. In my day-to-day clinical work, I feel keenly that a situation has emerged where, for young people in particular, life and death appear to have come into closer proximity. If living seems to be a shallow undertaking, people will see its various hard-to-avoid trials and difficulties as meaningless, a waste of time, and irrational. And they will lack the will to overcome them. It is unsurprising that death comes readily to mind as a route of escape.

The Consolations of Culture

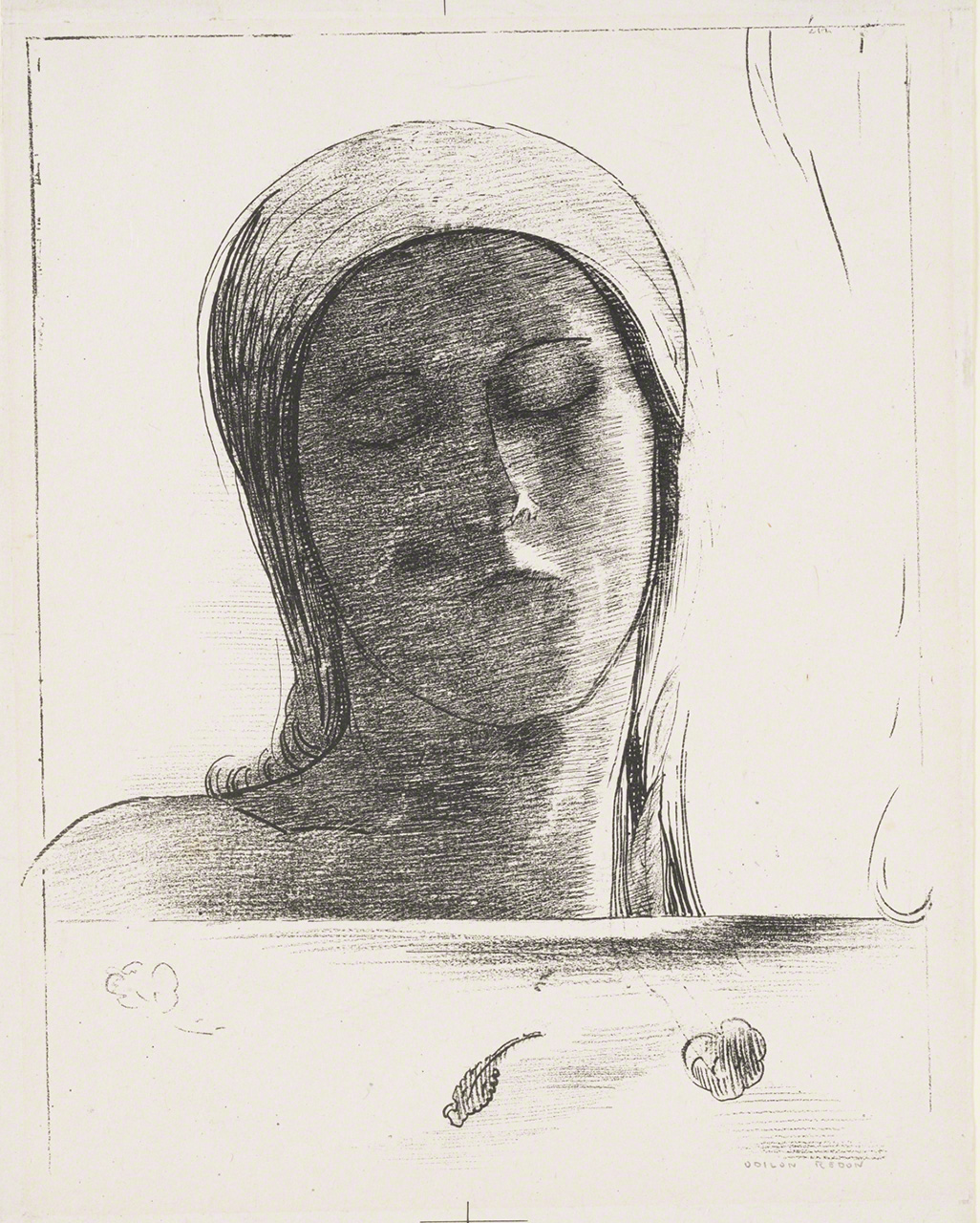

Odilon Redon, Yeux clos (Eyes Closed), 1890, lithograph on paper, The Museum of Fine Arts, Gifu. Displayed in the exhibition 1894 Visions Odilon Redon and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec at Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo. Courtesy Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum.

The poet T. S. Eliot wrote, “Culture may even be described simply as that which makes life worth living.” This indeed is the proper role of culture. It is not a distraction or a way of killing time—and certainly not an accessory worn to display one’s refinement.

Now, when self-reflection is unavoidable, we are much more likely than usual to notice that we are living with an inner void from which entertainment alone cannot divert us. But we need not blindly fear this emptiness. Our forebears have left us a great cultural legacy of works showing how people have faced up to it, discovered something in it, and overcome it. And in these works we are sure to find engagement with the invisible.

Amid the ongoing inclination toward the visible, pursuit of immediate results, and exaltation of handling problems with data and manuals, we are being pressed to once again confront the forgotten “invisible”. At the forefront of the flood of information, we see a plethora of data in the form of manuals, along with great quantities of content for our entertainment. But instead of letting our eyes stop there, I believe we need to look for the true wisdom that lies beyond in the form of culture that provides a purpose for living.

Ludwig van Beethoven, whose 250th birthday was celebrated recently, became deaf to the point that it seemed he could no longer continue as a musician. He considered suicide and even drafted a will. Yet in his struggle to overcome these difficulties, he expressed the deep meaning of life in such symphonies as his Third (Eroica) and Ninth. And Shakespeare brilliantly depicted the various forms of turpitude into which people easily fall in timeless plays that teach us what it means to be human. This sort of cultural heritage should not be kept in museums as a highbrow legacy. When we seem on the verge of losing sight of meaning, such works offer empathy with our feelings of emptiness and hints to where hope can be found.

Now more than ever, when there seems to be no way forward, we would benefit from individual engagement in quiet and thorough introspection. In approaching our inner existence, we must not be overwhelmed by the invisible, but use it instead as nourishment to create new culture and provide strength to conduct our lives. I believe it is here that the true inner strength of humanity will show itself.

(Originally published in Japanese on January 4, 2021. Banner image: Odilon Redon, Yeux clos (Eyes Closed), 1890, lithograph on paper, The Museum of Fine Arts, Gifu. Displayed in the exhibition 1894 Visions Odilon Redon and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec at Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo. Courtesy Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum.)

suicide Beethoven depression Shakespeare coronavirus COVID-19