Japan, China Mark Half-Century of Ties with an Eye on the Future

World Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Milestone Year Marked by the Taiwan Issue

On September 12 this year, an online symposium took place connecting audiences in Tokyo and Beijing, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the 1972 normalization of diplomatic ties between Japan and the People’s Republic of China. Cohosted by the business organization Keidanren and the Chinese embassy in Tokyo, the event was attended by figures from the Japanese side including former Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo, former speaker of the House of Representatives Kōno Yōhei, and Keidanren Chairman Tokura Masakazu.

The mood at the event, though, was considerably less than celebratory. Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, in a video message played at the event, stated baldly: “On major issues of principle essential to the very foundation of China-Japan relations, such as history and Taiwan, there must be no ambiguity, still less any wavering or backpedaling.”

Chinese Ambassador to Japan Kong Xuanyou, who delivered the keynote address at the event, noted that the previous half-century had indeed seen a welcome increase in Sino-Japanese exchange and cooperation. At the same time, though, he demanded that the Japanese government take a very cautious stance on the Taiwan issue, in effect firing shots across Tokyo’s bow with respect to the question of the island.

Taiwan is, indeed, the number-one stumbling block in the way of smooth relations between Japan and China, not to mention between the United States and China. When Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the US House of Representatives, visited Taiwan in early August this year, it triggered a fresh round of People’s Liberation Army military exercises displaying the capability to encircle the island, including China’s first-ever launch of ballistic missiles into Japan’s exclusive economic zone.

From Honeymoon to Harsh Weather

On September 29, 1972, Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai signed the joint communiqué between the two governments that restarted diplomatic ties. In the following month, two pandas, the female Lang Lang and male Kang Kang, arrived at Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo, highlighting the launch of a warmer era in bilateral ties.

Japanese economic cooperation with China got its full-fledged start in December 1979, when Prime Minister Ōhira Masayoshi visited Beijing, and this provided the impetus for the Chinese authorities to press ahead with their policy of reform and opening. A decade later this trend was cut off with the June 1989 Tiananmen protests and massacre, which sparked Western economic sanctions and cut China off from the international community. It was Japan, though, that moved first to bring about a thaw in this freeze, with the administration of Prime Minister Miyazawa Kiichi laying the groundwork for an October 1992 visit by Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko to Beijing, Xian, and Shanghai.

The 1990s saw a change in this warming dynamic, though. Japan’s economic bubble collapsed, and the country headed into an extended period of sluggish growth. China, meanwhile, stepped out with a more muscular stance on the diplomatic and military fronts, including nuclear weapons tests in June and July 2006 that brought harsh condemnation from Tokyo. The economic front was no less stormy in the region, with July 1997 seeing the beginning of the Asian currency crisis. Add to this repeated standoffs between Beijing and Tokyo over history issues, and it was clear that the countries had entered a markedly cooler period in their bilateral relationship.

Once Koizumi Jun’ichirō took office as Japan’s prime minister in April 2001, his regular visits to the problematic Yasukuni Shrine triggered harsh responses from China. The five and a half years he spent in office would be viewed as perhaps the roughest period in Sino-Japanese ties since they were reforged in 1972.

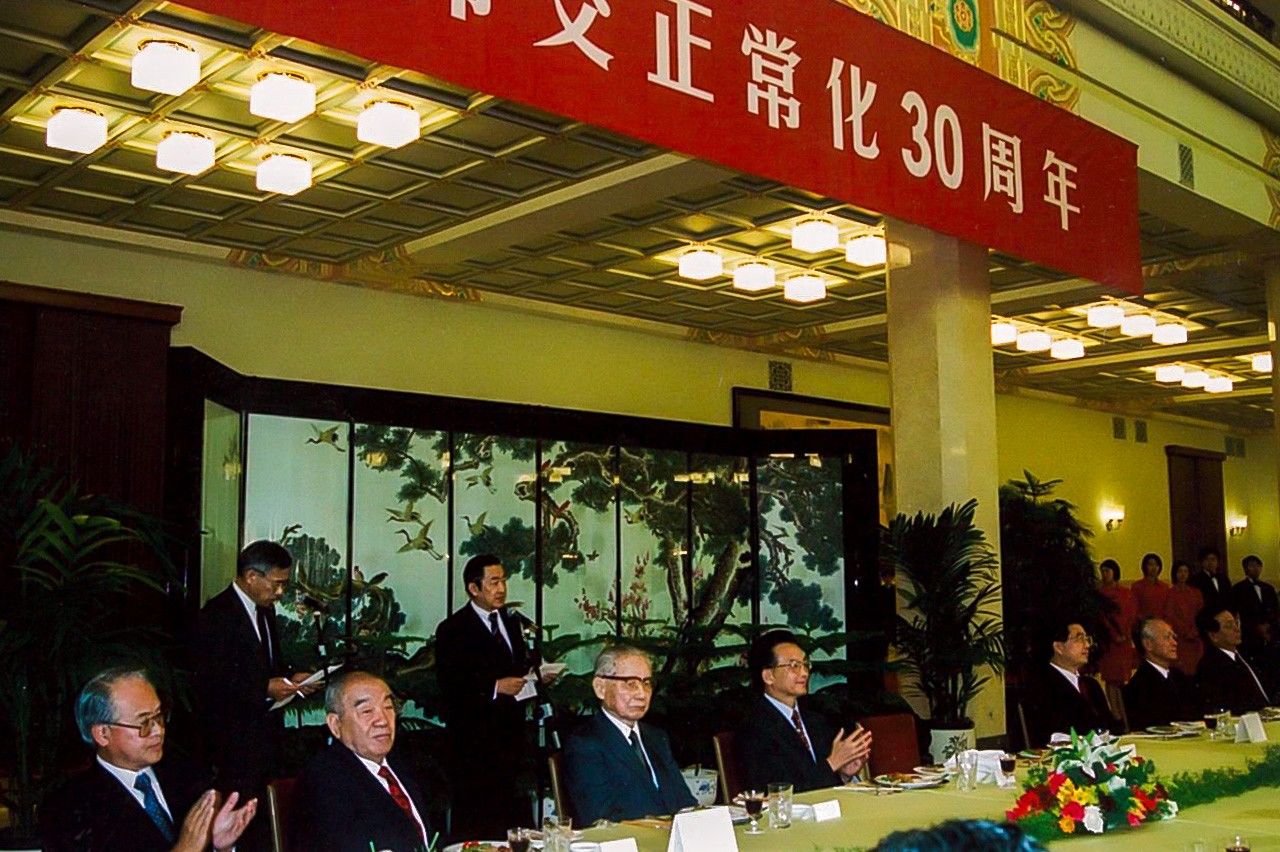

During this period, though, an event took place at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on September 28, 2002, to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the normalization of the relationship. In attendance from Japan were former Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi, former Deputy Prime Minister Gotōda Masaharu, and the celebrated painter Hirayama Ikuo; another former prime minister, Hashimoto Ryūtarō, gave a speech. Seated at the same head table were Vice Premier Hu Jintao and Deputy Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, both of whom would go on to serve in top Chinese leadership posts.

Former Japanese Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryūtarō gives a speech at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People to mark 30 years of Sino-Japanese ties. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

While I was stationed in Beijing, I heard Wang Yi, now foreign minister, describe the ties between Japan and China as follows. “When we normalized diplomatic ties we were like newlyweds. For a period thereafter we enjoyed a honeymoon, but as time passes, any couple will see some friction arise.” By this marriage-based reckoning, in 2002 our countries marked their pearl anniversary, the thirtieth; this year, September 29 was the golden anniversary for Japan and China.

Abe Shinzō’s Work for Warmer Ties

The beginning of the century was described as “politically cold, economically hot,” or frosty in political terms, while the countries forged ever-warmer economic connections. As noted above, the Koizumi administration marked a wintry era for the bilateral relationship. It was Abe Shinzō, lost to an assassin’s gun in July this year, who helped to bring about a thaw.

Soon after Abe took office for the first time as prime minister, on October 8, 2006, he visited China and met with Premier Wen Jiabao and President Hu Jintao. This was the first step toward rebuilding a “mutually beneficial strategic relationship” between China and Japan.

Laying the groundwork for this dramatic visit had been Wang Yi, then China’s ambassador to Japan. Born in 1953, Wang celebrated his birthday on October 8, and it was said he arranged the meeting with this date in mind. The Japanese phrase corresponding to the “mutually beneficial strategic relationship,” meanwhile, was apparently the brainchild of the diplomat Tarumi Hideo, who today serves as Japan’s ambassador in Beijing.

Abe would again take office as prime minister in December 2012. Just ahead of this, in September that year, the administration of Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko nationalized the Senkaku Islands, part of Okinawa Prefecture, which China claims as its own territory. This took place just ahead of the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, held every five years, and it brought a severe chill to bilateral ties, with large-scale anti-Japanese protests erupting across China.

In November 2014, Abe again visited China, where he met with President Xi Jinping. The two sides recognized that they held differing views on the Senkaku issue, but reached a four-point agreement including a determination to use dialogue and consultation to prevent the deterioration of the situation. This short summit lasted just 25 minutes, and the leaders bore stern looks throughout the meeting, but they shook hands and took a commemorative photo at the end.

Xi Jinping, right, and Abe Shinzō shake hands after their brief summit meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on November 10, 2014. (© Jiji)

On July 9 this year, the day after Abe Shinzō died in a shooting attack in Nara, Xi sent a telegram of condolences to Prime Minister Kishida Fumio. In it he praised the late politician, stating: “Former Prime Minister Abe worked for the betterment of Sino-Japanese relations while in office, making valuable contributions.”

Turning back once more to the November 2014 Xi-Abe summit, we should note that it was Fukuda Yasuo, Japan’s prime minister in 2007–8, who laid the groundwork for this meeting. In July 2014 he paid a secret visit to China together with Yachi Shōtarō, then director-general of the National Security Secretariat, where the two met with Xi. They also spoke with Foreign Minister Wang Yi and State Councilor Yang Jiechi, with whom they made progress on the four-point agreement that would be reached later that year between Xi and Abe.

Fukuda Yasuo and Wang Yi could be considered “old friends” of a sort, with a relationship going back some 20 years even at that point in 2014. In August 2008, when Fukuda was prime minister, he attended the Opening Ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games; he also served as director-general of the China-driven Boao Forum for Asia, among other moves cementing his solid connections with Beijing.

In 1978, Fukuda Yasuo’s father, Prime Minister Fukuda Takeo (in office from 1976 to 1978), signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Japan and China. From father to son, two generations of this family were involved in developing ties between the leaders of these two countries.

Trust-Building Politicians on Both Sides

If I may be permitted a personal recollection, in April 1988, I took my first trip to China as a newspaper journalist accompanying Itō Masayoshi, then the chairperson of the Liberal Democratic Party’s General Council. This was the beginning of my true professional interest in China, and Asia more broadly.

Takeshita Noboru, then prime minister, had dispatched Itō to Beijing as a personal envoy; on April 19, he met with Deng Xiaoping, chairman of China’s Central Military Commission and effectively the supreme leader of the country, at the Great Hall of the People.

Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, at left, speaks with the Japanese LDP’s Itō Masayoshi on April 19, 1988, at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

“I’ve met with any number of Japanese politicians,” said Deng to Itō, “but I’ve met you more times than any of them. We truly are friends who can open our hearts to one another.” Camera in hand, I was present as a member of the press corps, but I remember feeling a sense of real closeness between these two elder statesmen.

Indeed, Deng (then 84) and Itō (74) were taking part in their sixth meeting. In June the following year, the Tiananmen Square massacre took place, but soon afterward, it was once again Itō who served as one of the first representatives of the world’s advanced democracies to go to China, where he saw Deng for the seventh time, helping to open a way for Beijing to return to the community of nations.

Why was Itō, who served as head of the Japan-China Friendship Parliamentarians’ Union, able to win this level of trust from the Chinese side? Firstly, he had an intimate knowledge of the current state of affairs in China at the time. Also enhancing his reception in China was the fact that he had been critical of Japan’s military actions during the second Sino-Japanese War.

A graduate of the law department at the elite Imperial University of Tokyo, Itō was a bureaucrat at the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry before being seconded to the East Asia Development Board, an agency-level organization launched late in 1938 to coordinate Japan’s continental policy. While there he served in Shanghai. Ōhira Masayoshi, who would go on to be prime minister in 1978–80, was seconded to the EADB from the Finance Ministry at the same time, and the two hit it off, becoming lifelong friends.

In 1943, Itō received his orders calling him up for military service. He was qualified to become an officer, but something in his humble Aizu, Fukushima, roots made him averse to the idea, and he chose not to take the officer candidates’ examination. I remember him reminiscing about the rough treatment this brought him, like the time when a private first class had struck him, sending his eyeglasses flying.

Negative Impressions to Overcome on Both Sides

The history of ties between Japan and China actually goes back some 2,000 years. Premier Zhou Enlai, one of the architects on the Chinese side of the 1972 reestablishment of diplomatic ties, described this relationship as “2,000 years of friendship and 50 years of confrontation,” with the latter period being the half-century from the first Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 through the end of World War II in 1945.

How, then, can we characterize the half-century that has passed since Japan and China restarted their diplomatic relationship in 1972? Fifty years ago, fewer than 10,000 people a year traveled between the two countries. This number had climbed as high as 12 million just before the COVID-19 pandemic brought the numbers crashing back down again. Economic ties have also blossomed, with China today being the largest trading partner for Japan.

Despite all this, national sentiment on both sides has been worsening for some time. In January this year Japan’s Cabinet Office published the results of the Public Opinion Survey on Diplomacy implemented in September–November 2021. Compared to the previous survey, carried out in October 2020, the percentage of respondents who thought Japan-China ties were good fell 2.6 points to 14.5%; those who did not think they were going well, meanwhile, climbed 3.4 points to 85.2%.

Similar results were produced by the Japan-China Public Opinion Survey carried out by Genron NPO, a nonprofit Japanese thinktank, and the China International Publishing Group in August–September 2021. In China, the percentage of respondents with a poor opinion of Japan rose 13.2 points from the previous year to 66.1%, while in Japan, those with a poor opinion of China climbed 1.2 points to 90.9%.

In September 1997, a quarter-century after the normalization of ties, Sun Pinghua, chair of the China-Japan Friendship Association—who had also laid the groundwork for Prime Minister Tanaka’s 1972 Beijing visit and was close to Itō—contributed a series of pieces to the Watashi no rirekisho (My Resume) column in the Nihon Keizai Shimbun. In the first installment, he wrote:

“For both Japanese friendship with China and Chinese friendship with Japan, the most important thing is the same: relations between human beings. I believe it is key for people to get along with one another, heart to heart. In this sense, I fear that China-Japan ties in recent years have lacked these emotional underpinnings.”

Indeed, as the two nations marked the “silver anniversary” of their modern bilateral relationship, ties were not particularly good. Nevertheless, in the Japanese government’s Public Opinion Survey on Diplomacy carried out in September–October 1997, respondents with a positive view of Japan’s ties with China outnumbered those with a negative view, at 45.6% to 44.2%.

“A Duty to Our Descendants”

The Sino-Japanese relationship in the twenty-first century is no longer one to be analyzed simply in terms of bilateral ties. These are the second- and third-largest national economies in the world, and confrontation between these countries would have a severe impact on the global economy as a whole. World affairs remain unstable, with the Russian war against Ukraine added to the continuing pandemic. Today more than ever, Japan and China must work in partnership to maintain stable ties and contribute to the international community.

On September 12 this year, Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs Hayashi Yoshimasa presented a video message at a symposium held to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the restoration of diplomatic ties. In it he laid bare his determination to improve ties with Beijing: “It is a responsibility handed down from our ancestors, and a duty to our descendants, to build a constructive, stable Japan-China relationship through conscious efforts by both countries.”

Before being tapped as foreign minister, Hayashi was chief of the Japan-China Friendship Parliamentarians’ Union. His father, Hayashi Yoshirō, also held this post while he was in the Diet, in addition to serving as head of the Japan-China Friendship Center. Father and son alike are deeply involved in their nation’s ties with China.

Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, of course, is another politician whose career runs in the family—his father, Kishida Fumitake, and grandfather, Kishida Masaki, both held seats in the House of Representatives. The prime minister served a lengthy term as foreign minister (2012–17), meeting numerous times with key members of the Chinese leadership. His counterpart in Beijing, President Xi Jinping, is yet another dynastic political figure: His father, Xi Zhongxun, was among the first generations of leaders in the People’s Republic of China, serving in posts including vice-premier under Zhou Enlai.

Looking ahead to the next 50 years, how will the Japan-China relationship continue to develop? The current leaders of the countries, both hailing from long-standing political lineages, bear great responsibility for the construction of this relationship.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Former Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo delivers the keynote address at a Tokyo symposium celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the normalization of Sino-Japanese diplomatic ties on September 12, 2022. © Xinhua/Kyōdō Images.)