The Government Program Helping Outsiders Inject New Energy into Regional Communities

Society Economy Lifestyle Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Numbers Increasing Year-on-Year

Television, newspapers, and online media are increasingly focusing on life away from Japan’s big cities. In recent years, increasing numbers of young people have started to think seriously about relocating away from Japan’s crowded urban centers to start a new life in rural communities.

Run with financial support from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Local Vitalization Cooperator program sponsors people who are interested in relocating to these communities. The volunteers live in their chosen region for a period of one to three years, helping with various community regeneration projects including village reenergization, tourism, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and cultural heritage. The idea is that participants will consider settling permanently once their contract comes to an end.

Participants are guaranteed an income for the period of their service. The exact amount varies according to region, but can reach up to ¥4.8 million per participant, funded out of special regional distribution taxes. A condition of the program is that participants relocate their official address and residential record (jūminhyō) to the region where they work, and publicize their activities using social and other internet media.

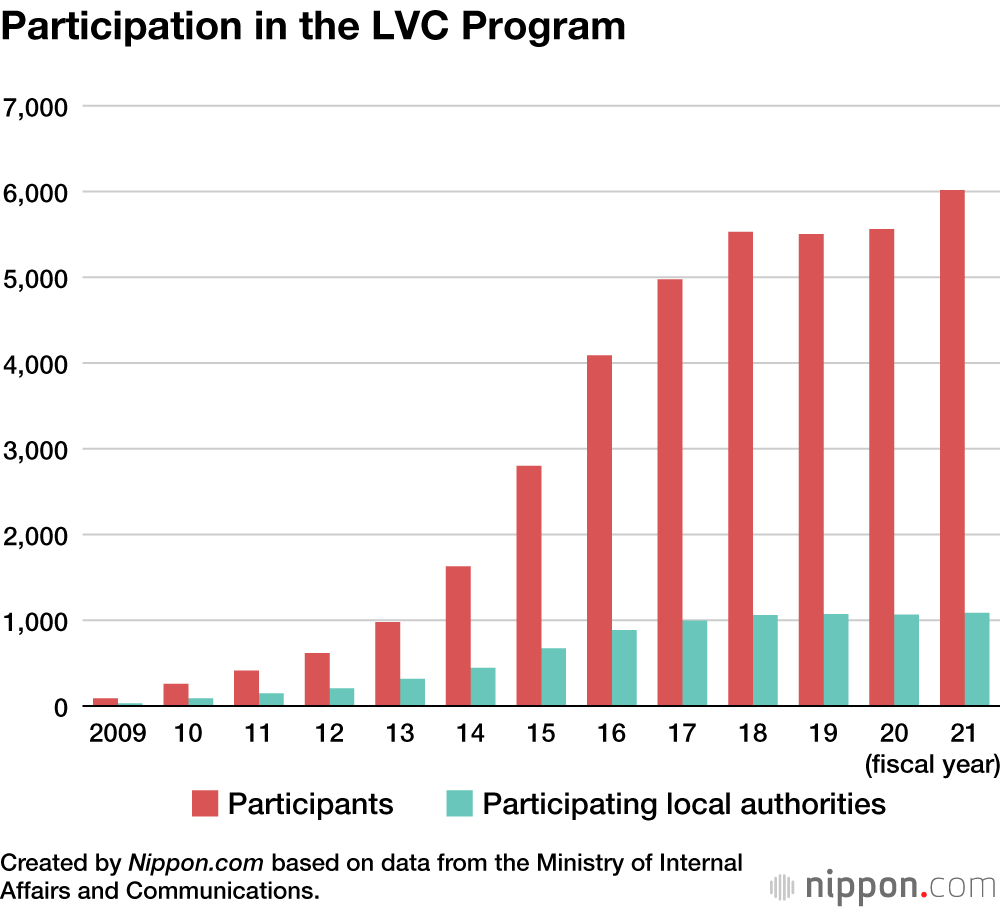

The project started in fiscal 2009 (April 2009 to March 2010), and attracted 89 participants during its first year. This number grew to 257 in fiscal 2010 before increasing rapidly, by 30% and 50%, in its fourth and fifth years. In fiscal 2021 the number increased by 455 from the previous year, to 6,015. Fully 70% of participants were in their twenties and thirties, and around 40% were women.

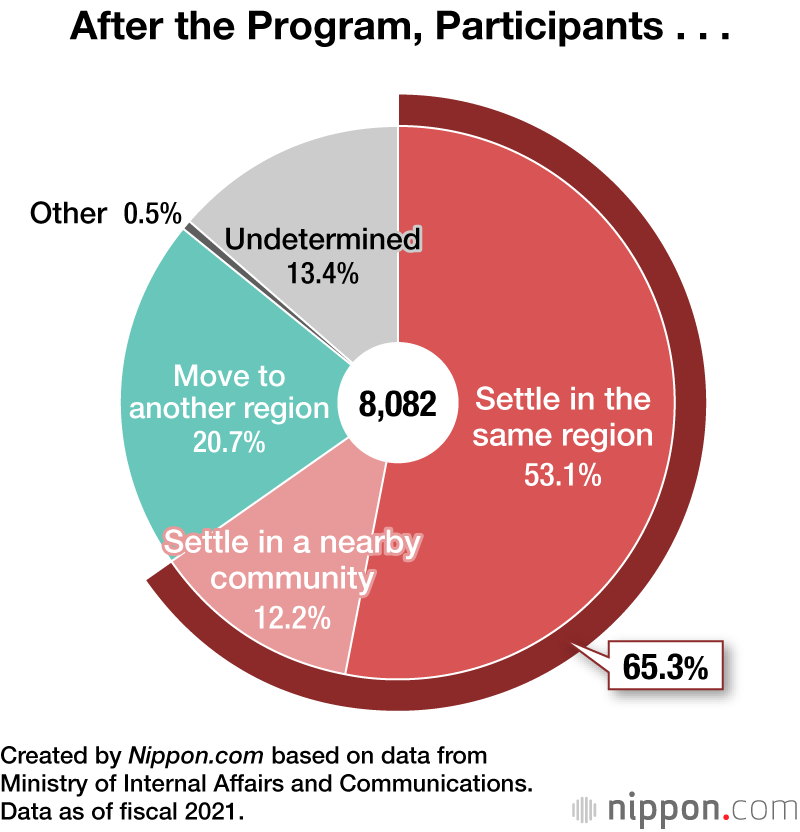

In addition, as of fiscal 2021, of the 8,082 people who have completed the program, some 5,281 (65%) decided to stay on and are still living in the same regional community. Some have taken over traditional businesses in a wide range of fields, including sake brewing, washi paper making, running accommodations, and soy-sauce wholesaling. The total includes 140 foreign nationals, including people from South Africa, China, Hungary, and Costa Rica, who are working in diverse ways to bring out the potential of Japan’s regions and ensure a new and brighter future for these marginalized communities.

“Young people’s values are more diverse these days,” says Shiikawa Shinobu, the government official who came up with the idea for the program. Shiikawa previously served as director of the Local Public Finance Bureau in the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, or MIC, and now heads the Japan Center for Regional Development. During his time at MIC, Shiikawa was asked to propose a policy that would bring new energy to Japan’s senescent rural communities. He came up with the idea for the current program after a series of interviews with experts in relevant government ministries and agencies and people who had worked for the Japan International Cooperation Agency or served as JICA Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers. Using the special local allocation tax allows activities to run across multiple fiscal years, unlike the single-year framework that would be possible with a direct grant from the government.

Shiikawa feels that young people are ready to make the move sooner than was previously the case. “Low economic growth has continued for more than twenty years now—for many young people, that’s all they’ve ever known. Not surprisingly, many of them are open to the idea of making a new start.”

This trend is having a positive impact on regional communities, and bringing new life—sometimes literally-to rural parts of Japan. In the Irokawa district of Nachi Katsuura on the Pacific coast of Wakayama Prefecture, a young couple who relocated to the area recently welcomed the first baby to be born in the district for 38 years. In Tsushima in Nagasaki Prefecture, an ecologist in her twenties who previously worked at Tōhoku University moved to a small village where the other residents are all over 70, where she founded a start-up that collaborates with universities and arranges for young people to move into the community from outside. Now married with children of her own, she continues to work hard on regional energization activities.

Learning New Skills as a Grape Farmer

For this article, I spoke to two participants who relocated to Tochigi Prefecture as part of the program.

Around two hours north of Tokyo lies the small town of Mashiko, famous for its local style of pottery. Working in this rural town is 27-year-old Hashimoto Rei, originally from Hokkaidō, who relocated to Tochigi to cultivate grapes. After studying ergonomics at university, Hashimoto joined an IT company in Tokyo, but found himself increasingly drawn to agriculture. He was looking around for opportunities when he learned that a grape farmer in Tochigi Prefecture was looking for someone to take over the business, and promptly applied. Around 20 farms in Mashiko today grow grapes, pears, apples, blueberries, and other fruits. Roughly 80% of them have no one in place to take over when the current owners retire.

Hashimoto joined the LVC scheme in May 2020, and since then has worked at a greenhouse vineyard owned by Fujisawa Satoko, tending vines that range in age from 25 years to more than 40. The vines produce several sought-after varieties of premium grapes.

“Our children found work outside the area and couldn’t take over the business,” Fujisawa says. She and her husband were part-time farmers, growing grapes alongside factory work. “When my husband became ill, he went to the local municipal office with the intention of giving up the vines and closing the business. But town officials said it would be a waste to let the vines go, and volunteered to help us look for someone to keep the business going.” The next day, her husband succumbed to his illness.

“Hashimoto-san takes care of everything all by himself, including pruning the vines. It’s great having someone young and fit to keep the place going,” says Fujisawa with a grin when I visit her and Hashimoto in a workspace close to the vines.

Hashimoto with vineyard owner Fujisawa Satoko in the farm shop.

The work is not easy. Hashimoto gets up before five and is in the greenhouses tending the vines by six every morning. At seven-thirty he delivers grapes to a michi-no-eki roadside market that sells local produce and souvenirs. He works until around five in the evening. During the harvest, from mid-August until early October, he takes no days off. The work is year-round, though. In spring he thins out the vines by selecting the most promising buds, and in June prunes back the flowering grapes to keep the vines in order. When the flowers bud, he uses the plant hormone gibberellin to ensure that the resulting grapes grow without seeds. When the grapes reach the necessary size, he removes any fruit that is in danger of being crushed. The work involves lots of looking up. Repeating the process more than 10,000 times is enough to put a crick in your neck, Hashimoto says with a rueful grin.

Hashimoto trained for a year at an agricultural college in Utsunomiya, the Tochigi capital. “You have your own vines and are responsible for cultivating the grapes. You have to think about all the little details yourself, including how and where to invest your money. It’s something you could never experience in any other kind of training. And because the project is affiliated with the town, everyone is always ready to help.” Of course, Hashimoto has to take responsibility for any failures or damage to his crops. But he makes all the important decisions himself. “Learning any new business can be intimidating,” he admits, “but I really enjoy having the freedom to make my own decisions. I wouldn’t change that for anything.”

At the moment, Hashimoto gets a monthly paycheck from the Mashiko government, but that guaranteed income comes to an end April next year. Making enough money to live on is likely to be a challenge at first. Hashimoto says he is eager to move on from his current subsidized apartment to a traditional Japanese house where he would have more storage space, but is struggling to find a suitable place to rent at the moment.

Hashimoto’s first objective is to make a secure living here by raising growing grapes. He has plans to expand the business, processing smaller grapes into juice, and growing other fruits including persimmons and figs at different times of the year. His eyes glint as he talks excitedly about the new challenges he wants to take on in the years ahead.

From Tourist Promotor to Guesthouse Owner

Just over an hour north from Tokyo on the Shinkansen lies the city of Nasushiobara, famous for its hot-spring resorts. One stop on the local line from the Shinkansen station is Kuroiso station.

A three-minute walk from the station is the guesthouse Matinee. The owner is Toyoda Ayano, aged 31. “I majored in sociology at Rikkyō University, so I often used to see articles and information about the program. Then in my final year, when there was nothing left except to write my graduation thesis, I decided that I wanted to apply.” Why did she choose to apply to Nasushiobara in particular? “I considered other options too, but this town felt as though it was just in between the city and more rural areas, and the transportation links are good too. I liked the balance.”

Toyoda poses at the guesthouse entrance.

The stretch of Tochigi Prefectural Route 369 that leads from Kuroiso Station to the Itamuro hot springs is the venue for the Art 369 project, which has brought numerous attractive new art spots and shops to the region. Attractions include an exhibition space featuring works by popular contemporary artist Nara Yoshitomo and the landmark 1988 Café Shōzō, built in a renovated traditional house, which draws devotees from around the country, and a record shop owned by leading street music figure B.D., also known as Killa Turner. Toyoda says this was part of what attracted her to the town. “I’d heard that new facilities were going to open, and it just felt like the right place at the right time,” she says.

From October 2014 to September 2017, Toyoda was worked in tourism publicity for the town on the LVC scheme. During her time on the program, she invited an overseas vlogger for a tour of Nasushiobara, created a series of Line stamps to promote the town on the popular social media network, and helped to set up the tourism department within the local city government. Three years ago, she got married. Her husband works for an IT company in Tokyo. The couple officially moved their residential address to Kuroiso, and currently divide their time between Tokyo and Kuroiso.

As a university student, Toyoda took a year off from her studies and went on a trip around the world. “When I went to Israel, I realized how the presence of guesthouses all around the country meant that travelers could feel safe and be welcomed by local people in the communities they visited. The guesthouses also served as places for local people to publicize themselves their communities to the outside world. That’s when I got the idea that I’d like to create a place like that myself someday.”

Taking in the view from one of the upstairs rooms

The guesthouse was a personal project, which Toyoda worked on outside of office hours. But she often spoke of her guesthouse dream to city-hall colleagues and people she met about town. Many of these people helped her to find an empty house and introduced potential guests. Her activities on the program brought her into contact with a wide range of people, including local dairy and other farmers. “Promoting the town, you meet all kinds of people, and before I realized it I had built up connections with so many in the community.”

The communal kitchen on the guesthouse’s second floor.

The first floor of the guesthouse is a gallery space exhibiting works from the Art 369 festival. On the second floor is a large tatami room and a communal kitchen where guests can gather and socialize. On the third floor are two more tatami rooms. Toyoda has enjoyed taking a DIY approach to the job of renovating the traditional Japanese architecture of the guesthouse, including ranma carved wooden panels, sliding doors, tatami, and futons to suit contemporary tastes. The rooms are popular with groups, and Toyoda has already welcomed film crews working on location nearby and university study trips.

The attractive ranma panels are among the attractive features of the tatami rooms on the third floor.

In addition to running the guesthouse, Toyoda also works as a consulting assistant and as a home tutor. “I want the guesthouse to be my main source of income, but I like combining different jobs,” she says. “My ambition is to build my own life here that matches my interests and personality, and share my experiences with other people.”

A Quiet Revolution in the Countryside

Former Ministry of Internal Affairs official Shiikawa says the aim of the Local Vitalization Cooperator program is not necessarily for participants to settle permanently in a region. “If that happens, great—but that’s not necessary for the program to succeed. The idea is for people to try living somewhere different for a few years, and to develop a connection with that place. If they then go on to support that community, to become a ‘fan’ of that region, if you like, then we’ve achieved our aim.” Discussing expectations on both sides before participants start their jobs can help avoid mismatched expectations.

Most of Japan’s rural regions have shortages of labor in just about every field. “People in the big cities tend not to think about the world beyond the life they know. They tend to believe, quite wrongly, that there’s nothing money can’t buy.” Shiikawa himself experienced life outside the city during his time working for the ministry, in Shimane and Miyazaki Prefectures. “It’s a reality that’s hard to notice when you’re living in the city, but the problems we face as a society—water, food, even human resources—all start in rural places and collect in the big cities.” And he sounds a warning for the future. “Unless we protect our rural communities, there is no future for Japan.”

“If people leave the area where they have grown up and move to the big city, their children and grandchildren grow up in the city. In the space of three generations, the connection to the old hometown is lost, and there are no longer any grandparents or other relatives living in the community. But relocating takes courage. It involves uncertainty and worries. By providing a guaranteed income for three years, this program helps people who might otherwise hesitate to take the step, and encourages them by providing advice and assistance with jobs and housing.”

Growing numbers of people, intrigued by the promise of experiencing a totally different side of life, are drawn to the possibility of relocating to a more rural part of the country to find more creative and meaningful work. Shiikawa believes a kind of chemical reaction occurs when incomers become part of the local community and locals become interested in their activities. These program participants are shedding new light on the resources and assets present in local communities. We may be seeing the first signs of a quiet revolution in Japanese society.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Hashimoto Rei, at left, and Toyoda Ayano. On the desk is a Danish wooden kendama left by a guest. All photos © Sawano Shin’ichirō.)