Japan’s Innovations in the Sporting World

OX Engineering: Building Wheelchairs for Sports and Life

Sports Economy Health Technology- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Building a Wheelchair Powerhouse

Since debuting its sports wheelchairs at the 1996 Paralympic Games in Atlanta, OX Engineering has come to be a dominant force in parasports. That year, athletes using OX chairs won two gold medals. Since then, OX chairs have racked up 144 total medals to date at the Winter and Summer Games, including a whopping 21 in Tokyo in 2021. Among this group is tennis legend Kunieda Shingo, who won three Paralympic golds with an OX chair.

So what makes OX chairs a cut above the competition? The answer lies in the company’s unusual founding.

OX Engineering started out in 1988 as the development arm of Sports Shop Ishii, a motorbike retailer established in 1976 by journalist and motorcycle racer Ishii Shigeyuki. Ishii invested heavily in equipment, creating a company that attracted motorcycle enthusiasts who were passionate about motorcycles and craftmanship, including current CEO, Yamaguchi Kōji.

CEO Yamaguchi Kōji at OX Engineering’s Chiba headquarters. (© Fuchi Takayuki)

When Yamaguchi joined in 1989, OX was already making wheelchairs, but none that were commercially available. Rather, they were for the personal use of Ishii, a former professional motorcycle racer who had been confined to a wheelchair after suffering a serious spinal injury in a test run in 1984.

Describing Ishii, who passed away in 2012, Yamaguchi says that he was well known in the industry. “I knew about his accident before I joined OX,” Yamaguchi recounts. “At the time, he was using a general-purpose chair issued under the social welfare system, but he found it lacking in terms of design and functionality. He would mutter that he didn’t want to be seen at the race circuit wheeling around in it. This drove him to modify the chair to make it look cooler.”

A major turning point for OX came when Ishii visited the IFMA International Bicycle and Motorcycle Show in Germany in 1990. Ishii’s chair caught the attention of local reporters, who praised its design. Although Ishii’s had initially been focused on creating a better chair for himself, the encounter opened his eyes to the broader commercial potential.

Entering the wheelchair market, OX from the start took a different approach to design than its established competitors. It saw chairs as a means of improving the lives of the physically disabled rather than simply as welfare and nursing equipment.

Ishii Nobuyuki’s modified wheelchair was a hit at the 1990 IFMA show. (© OX Engineering)

In his racing days, Ishii was a member of a high-ranking Yamaha team. (© OX Engineering)

Transferring Engineering Skills to Wheelchairs

OX Engineering launched the 01-M, its first general-purpose wheelchair, in 1992. Three years later, the firm reorganized its operations, shuttering its motorcycle unit to concentrate on wheelchairs. The decision was Ishii’s, but OX’s motorbike-loving staff did not raise opposition as might be expect by such a dramatic shift.

“I joined the company because I love motorbikes” Yamaguchi explains. “At the end of the day, though, me and everyone else here are engineers at heart.” He insists that this outlook allowed him to take the change from motorbikes to wheelchairs in stride. “The company’s main business had been to take bikes produced by big manufacturers and tune them for racing. If you start off with a poorly-performing bike, you’ll never win, no matter how hard you try. Ishii saw the writing was on the wall for the motorbike industry, and was excited about the wheelchair business, where he had a chance of starting out from scratch as a manufacturer.”

Just one year after OX Engineering shifted course, athletes using its wheelchairs won two gold medals at the Atlanta Paralympics. Although a new entrant to sport wheelchairs, OX successfully leveraged its knowhow and experience honed over years of preparing motorcycles for demanding races.

An engineer skillfully welds a wheelchair frame. (© Fuchi Takayuki)

Engineering knowhow acquired through motorbikes is put to use in crafting lightweight aluminum parts. (© Fuchi Takayuki)

Although boasting ample engineering prowess, Yamaguchi admits that OX employees lacked practical experience when it came to understanding the needs of physically disabled individuals. “We didn’t have a clear picture of how people with disabilities moved their bodies, or the kinds of wheelchair designs that would make it easier for them to play their sport,” he says. He asserts, however, that OX engineers managed to overcome this initial shortcoming through their uncompromising commitment to excellence. “Thanks to our small size, we weren’t bound by preconceived notions of wheelchairs and could try new things to see what worked.”

He notes that the wheelchair industry long enjoyed protection under Japan’s welfare scheme and that many of the entrenched ideas were at odds to an outsider like OX. One example was pricing.

OX caused a stir in the industry by offering its general purpose 01-M chair for ¥220,000, far above the standard price. Yamaguchi says that at the time, the government provided people with disabilities around ¥100,000 to purchase a wheelchair for day-to-day use. “As a result, wheelchair manufacturers worked within those parameters and tended not to develop new features in line with what users actually wanted,” he explains.

OX set its price tag based on a stance it had held since its days in motorcycle engineering; namely that some users would happily pay a premium for a good-looking, high-performing product.

The 01-M came with a controversial ¥220,000 price tag. (© OX Engineering)

The chair made waves in the industry. Many of the prefectural authorities charged with determining wheelchair policy saw OX as a rogue manufacturer that pressured disabled people into buying expensive products. Some even went as far as to disqualify OX chairs from the ¥100,000 grant program. In the most extreme cases, OX salespersons were banned from hospitals and forced to market their wheelchairs in parking lots. However, users came to OX’s rescue.

“Wheelchair users lobbied the government, saying that they had the right to use the ¥100,000 grant how they saw fit,” states Yamaguchi. “They let it be known that they wanted OX wheelchairs, even if it meant making up the difference themselves.” Through such efforts, OX chairs were made eligible for the welfare scheme.

For the first time, Japan’s wheelchair industry, which had until then only produced chairs that could be purchased outright with the grant, endorsed OX’s philosophy of delivering excellence even if it cost a little more.

Changing Attitudes to Disability

OX’s wheelchair business has continued to grow. The company has shipped over 75,000 chairs to date, with Competitive wheelchairs accounting for around 10% of the whole. Yamaguchi attributes much of the company’s growth to changing attitudes.

He says that when Tokyo hosted the second Paralympics in 1964 in tandem with the Olympic Games, the event was hardly covered on television or in the newspapers, reflecting the outdated view of disabled people existing on the fringes of mainstream society. “This began to change from the time that we became involved with wheelchairs,” he asserts. “Since then, wheelchair users have become more actively involved in society. I believe that our chairs have kept in step with the changing times.”

A selection from OX Engineering competitive wheelchair range. Clockwise from top left: tennis, basketball, and athletics wheelchairs (© OX Engineering)

Today, wheelchair users are part of broader society, including featuring in television shows and movies. This development was helped along by Beautiful Life, a TV show starring heartthrob Kimura Takuya that achieved an average rating of 32%. In the show, the female lead, played by Tokiwa Takako, rode a bright yellow OX chair.

“Rather than portraying wheelchair users as handicapped, Beautiful Life showed them as wanting to have fun and be fashionable, just like the rest of us,” says Yamaguchi. “Wheelchair users who watched the show liked the yellow chair, and many said they wished they had one like it.

OX’s wheelchair catalogue is much like a catalogue for motorbikes or bicycles. It features products in a wide range of colors along with a host of accessories, allowing customers to customize according to their tastes and needs.

OX’s high-end ZZR chair exemplifies the firm’s engineering prowess. (© OX Engineering)

Yamaguchi says that it is this commitment to give people what they want that has inspired some customers to refer to OX as the “Porsche of the wheelchair world.” He sheepishly welcomes the comparison. “Porsche is known for catering to its buyers’ very specific requests regarding logos and lights. At OX Engineering, we believe that we are just as good. We don’t think of ourselves as simply manufacturing wheelchairs—we are committed to making something that our customers will find pleasure in. This has been a steadfast philosophy from our days in the motorcycle industry.”

OX Engineering changed the way people think about wheelchairs by staying faithful to its founder’s philosophy. By creating well-designed chairs that people want to be seen in, OX has empowered wheelchair users to get out and make the most of their lives, an achievement that might be more important than its medal tally.

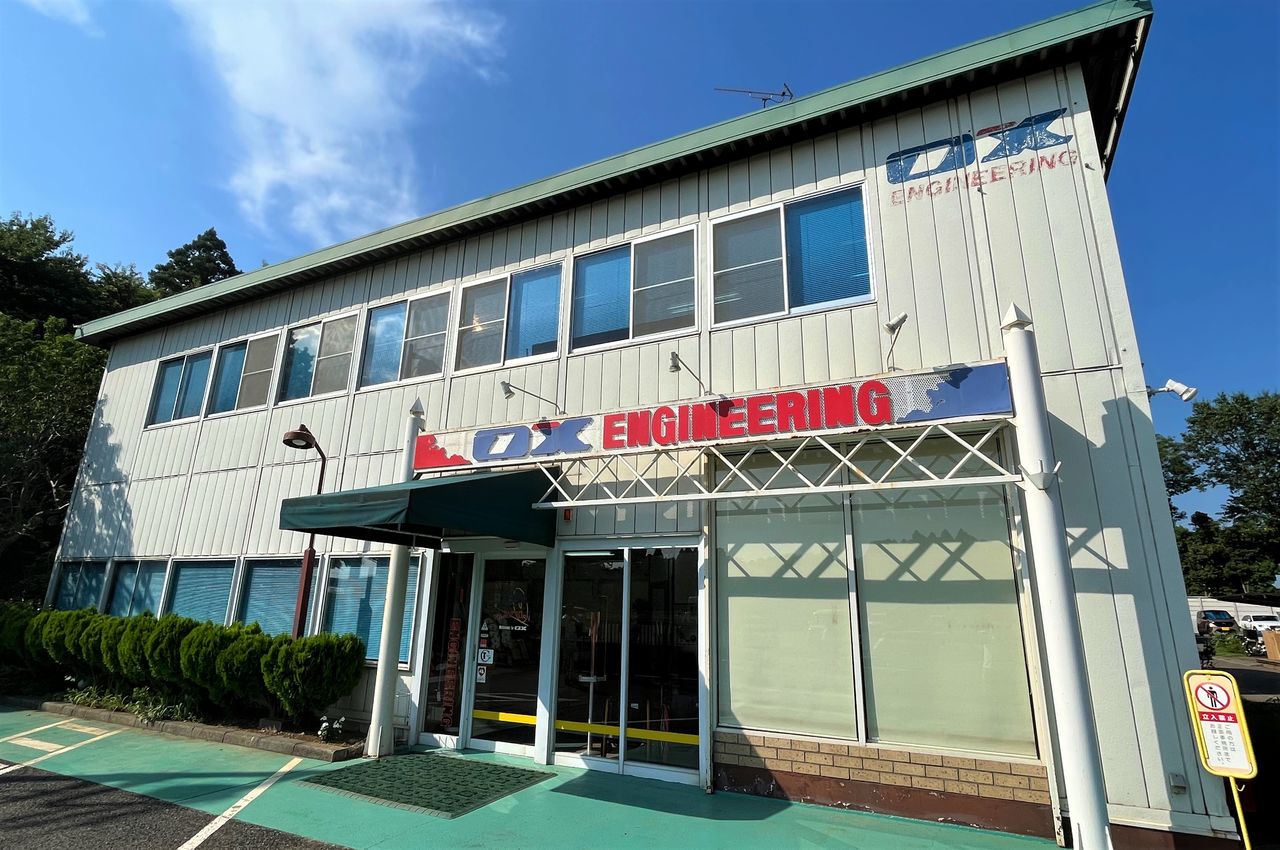

OX Engineering’s headquarters in Chiba Prefecture, where it manufactures competitive wheelchairs. It produces its general-purpose chairs at its factory in Niigata Prefecture. (© Fuchi Takayuki)

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo: Kunieda Shingo returns a shot in a French Open match on June 2, 2022. He won four world tennis championships and Paralympic gold in an OX Engineering chair. © AFP/Jiji.)