Hiroshima Welcomes the G7 Summit

Houses for Hiroshima: The Legacy of American Peace Activist Floyd Schmoe

- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Renewed Attention for an Unsung Helper

Hiroshima’s Eba district, part of the city’s bustling Naka Ward, will be familiar to admirers of the 2016 award-winning animated film Kono sekai no katasumi ni (In This Corner of the World) as the home of Suzu, the tale’s heroine. The work, set in wartime Japan, has raised interest in the area’s history.

When the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, Eba, lying some 4 kilometers southwest of the epicenter, was spared much of the destruction that leveled other parts of the city. Subsequently, it was inundated by the flood of wounded and homeless residents fleeing the shattered center of Hiroshima. Today, a nondescript wooden building standing in a quiet corner of the district serves as a reminder of efforts to ease the suffering of victims of the bombing.

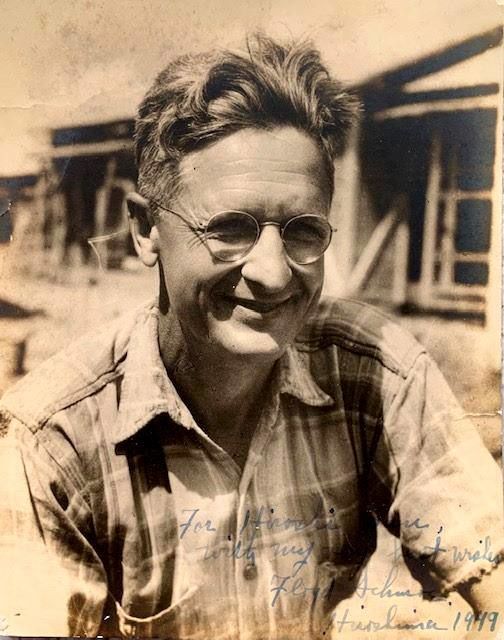

Built in 1951, it is the last of a number of dwellings and other buildings constructed as part of a housing project for residents of the ruined city. Initiated by American peace activist Floyd Schmoe (1895–2001), the undertaking, which came to be known as “Houses for Hiroshima,” brought together young volunteers from the United States and Japan.

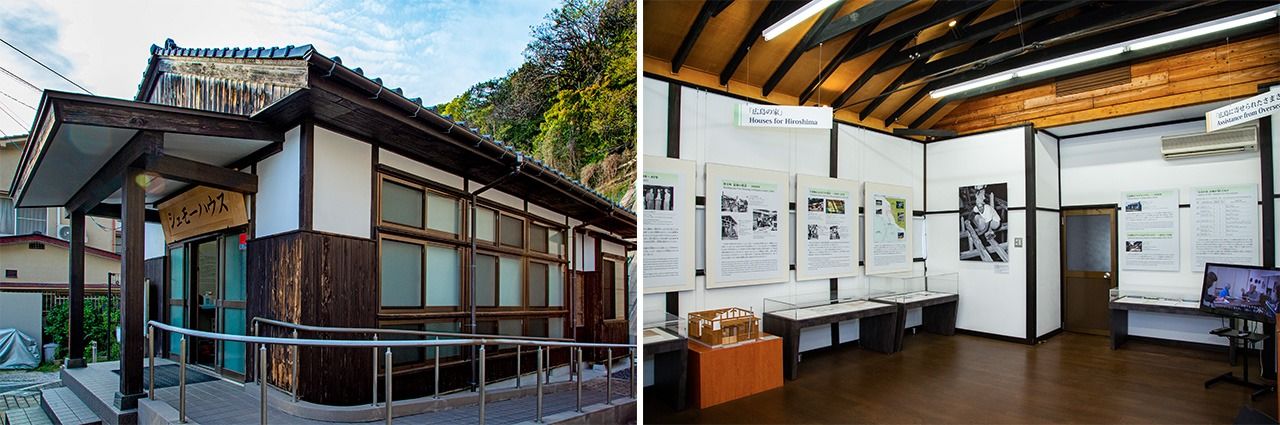

The tiny building originally served as a community center and was called “Schmoe Hall.” Since renamed Schmoe House, it is now an annex to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum that served to preserve the history of international aid work in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing.

The exterior of the Schmoe House in Eba and its interior exhibition space. (© Dōune Hiroko)

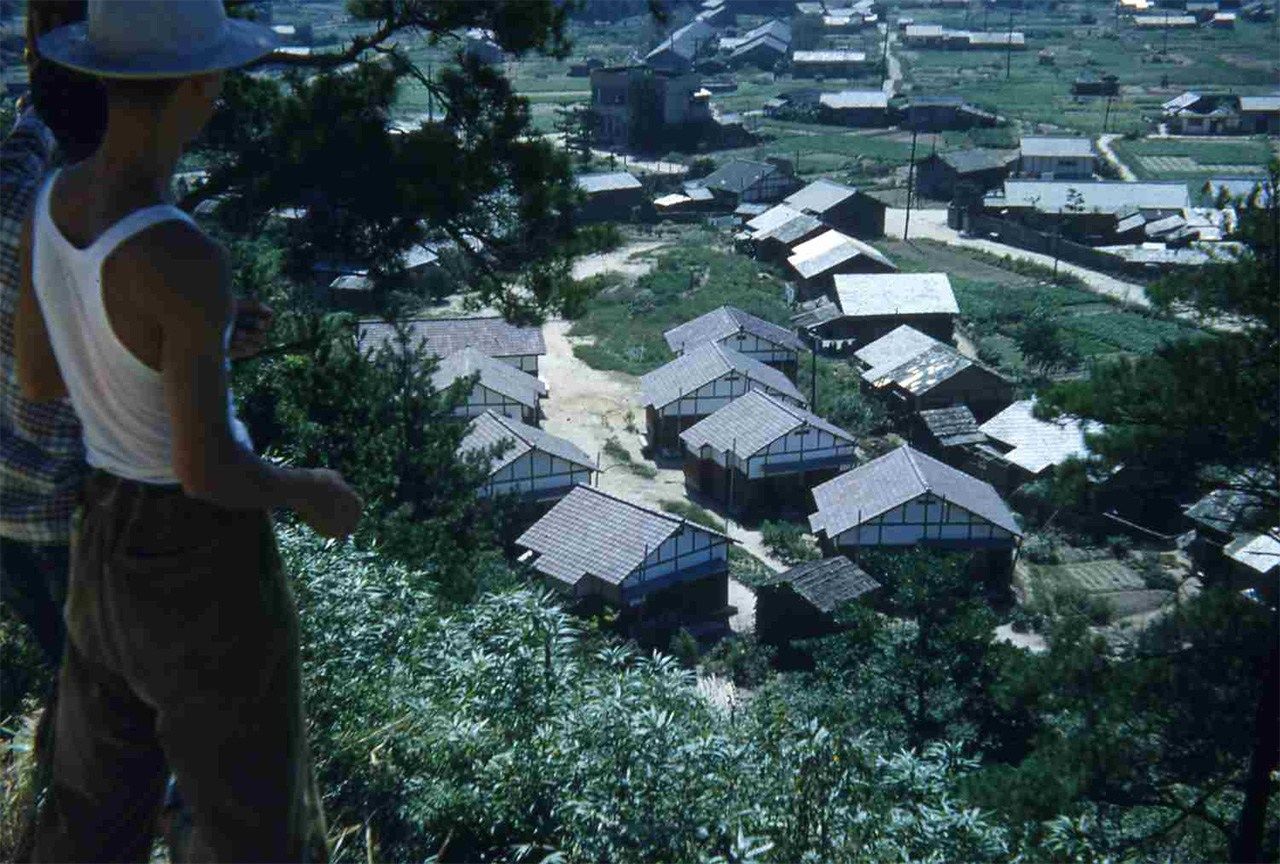

A photo of Eba seen from Sarayama. (Courtesy Tomiko Y. Schmoe/Shumō ni Manabu Kai)

Through the project, Schmoe, who hailed from Seattle, Washington, fostered a deep connection with Hiroshima and its residents, including Hamai Shinzō (1905–1968), who was mayor while the housing project was underway. In 1983, to express gratitude, Hiroshima made Schmoe an honorary citizen. But even with such honors, his contributions to the city inevitably faded from the minds of the general public. A small group of volunteers have been working to reverse this trend by shining a light on Schmoe’s legacy.

Sadako and the Thousand Cranes

The inspiration for their efforts started with a bronze statue in a Seattle park commemorating Sasaki Sadako, a young hibakusha bomb victim whose heart-wrenching story was retold in the children’s book Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes. In his later years, Schmoe, a Quaker and devout pacifist, began clearing a plot near the University of Washington, where he had been a professor of forest biology, to build a peace park. In 1988, he was awarded the Tanimoto Kiyoshi Peace Prize, named for a Japanese Methodist minister who devoted himself to the relief of A-bomb survivors and the peace movement, and used the money he received to complete the project. He was 94 when the park opened on August 6, 1990, the forty-fifth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Sadako’s statue, created by the artist Daryl Smith, was a centerpiece of the park. But in 2003, two years after Schmoe’s death at the age of 105, vandals senselessly disfigured the sculpture, sawing off its extended arm and otherwise damaging it. Hearing of the incident, the Seattle-based Japanese-American musician and activist Michiko Pumpian started collecting donations to restore the statue. Hearing of the campaign, Nishimura Hiroko, a volunteer at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, contributed funds and later attended a commemorative concert by Pumpian and others in Hiroshima.

Nishimura Hiroko. (© Dōune Hiroko)

Inspired by the experience, Nishimura began gathering information on Schmoe, but she says that surprisingly, there was little to be found. “Almost nothing remained in Hiroshima about his work,” she recounts. “He was dedicated to peace, toiling nonstop on different projects around the world, but he apparently didn’t give much weight to recording his activities.” Undeterred, Nishimura joined forces with fellow museum volunteer Imada Yōko, and together they formed a citizens group dedicated to preserving the legacy of Schmoe and the Houses for Hiroshima project.

Journey to Hiroshima

Moved by the suffering of A-bomb survivors, Schmoe came to Hiroshima in 1948 as part of a project organized by Licensed Agencies for Relief Asia, a broad collection of Christian aid groups and other organizations formed in 1946. Nurturing his idea for a housing project for displaced residents, he spoke with stakeholders and cobbled together $4,300 in donations. In 1949, he returned to the city with three colleagues—Emery Andrews, Daisy Tibbs, and Ruth Jenkins—to set his plans in motion. The group hired carpenters and gathered volunteers locally and from Tokyo, building four homes in the city’s Minamimachi area.

Floyd Schmoe. (Courtesy Maekawa Hiroshi/Shumō ni Manabu Kai)

Over the next five years, Schmoe helped construct housing and community centers for A-bomb survivors in four Hiroshima neighborhoods. These stood into the 1970s, but deteriorating with age, they were gradually demolished to make room for new structures. Of the 21 buildings constructed as part of Schmoe’s Houses for Hiroshima, the community center in Eba is the only one that remains.

One of the few accounts of Schmoe’s time in Japan is a booklet he penned that was translated into Japanese as Nihon inshō ki (Impression of Japan) and published by the Hiroshima Peace Center in 1952. In the work, Schmoe details his activities along with those of his American colleagues and the Japanese youth volunteers who participated in the project. In the preface, translator Ōhara Mihachi draws attention to Schmoe’s motivation for conducting relief work in Hiroshima, explaining that he was shocked and deeply hurt by the atomic bombing and was compelled to make amends for the suffering it inflicted. Ōhara quotes a letter Schmoe wrote to Jenkins, whom he called “Pinky,” in which he said that he wanted to demonstrate his sincerity by building houses for victims “to show the feelings of many American people who regret that innocent Japanese people suffered due to the bombing.”

Daisy Tibbs, left, and Emery Andrews haul supplies. (Courtesy Kitazawa Sumiko/Shumō ni Manabu Kai)

Using the booklet and other documents as her guide, Nishimura in 2004 began reaching out to former members of the Houses for Hiroshima project. Sitting down to talk with many of the participants, she used their stories to gradually paint a broader picture of the undertaking and to record developments after 1950, when Schmoe penned the booklet.

Other efforts to preserve Schmoe’s legacy began to emerge around the same time. Also in 2004, the mayor of Hiroshima unveiled plans to move the Eba community center, which stood in the path of a road expansion project, to a new location, saving it from demolition. Not long after, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum launched a project to study the treasure-trove of writings and other materials by Schmoe and his colleagues held at the University of Washington Libraries. This latter effort revealed a life dedicated to helping others.

During World War I, Schmoe refused military service as a conscientious objector, choosing instead to assist wounded soldiers and aid war refugees in Europe. Following the outbreak of World War II, he vigorously protested the internment of Japanese-American citizens and supported members of the Nikkei community in California. After the war, he turned his attention to aiding residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, building homes for A-bomb victims in both cities. In 1953, news of the refugee crisis in Korea reached him and he traveled to the peninsula to carry out aid work, including toiling alongside residents to build some 100 homes. Following the Suez Crisis in 1956, he headed to Egypt to assist refugees displaced by the conflict.

Ochiba Hironobu of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s Curatorial Division says that Schmoe’s work in Hiroshima reflects a hands-on approach to activism: “After the war, aid for hibakusha poured in from around the world, but Schmoe went one step beyond providing money and supplies. He was compelled to travel to Hiroshima and to live and work alongside the Japanese to assist those in need.”

Legacy of Friendship

Nishimura was moved by the far-reaching impact Houses for Hiroshima had on those involved in the project. She says that through the experience, the American and Japanese volunteers “forged deep and lasting connections.” She cites the account of one volunteer, who wrote that “the utter idiocy of war was brought home to me by our ability to go from being mortal enemies to trusted companions in four short years.”

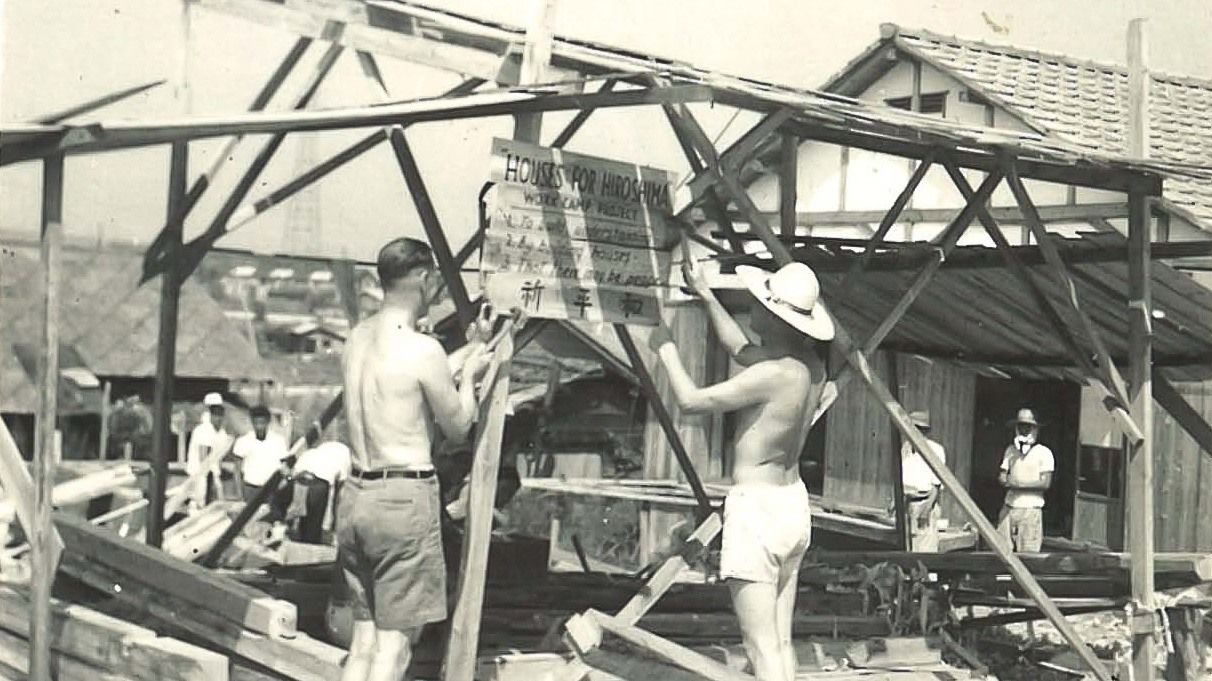

Japanese and American volunteers chisel beams. (Donated by Jean Walkinshaw/Courtesy Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

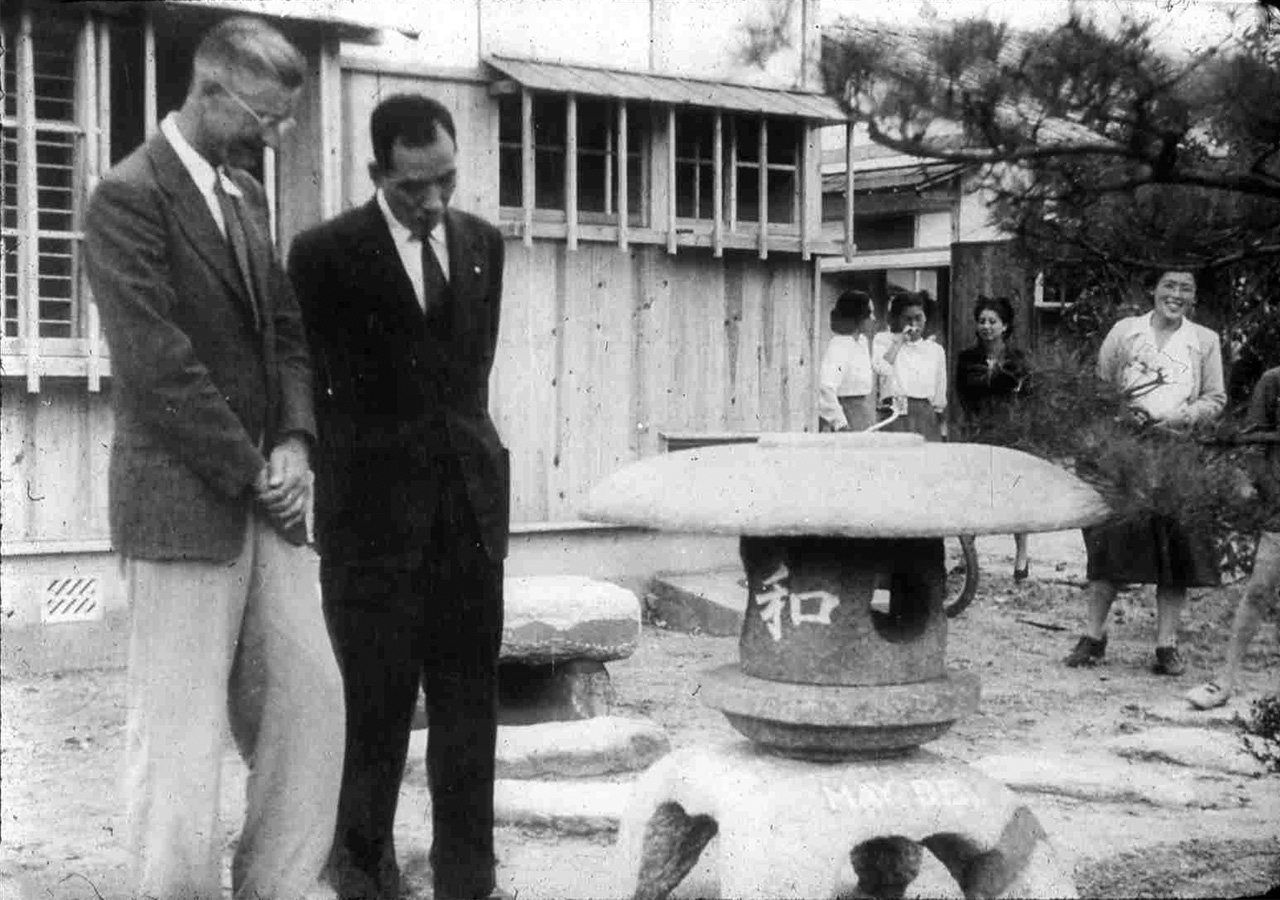

Schmoe, left, and Hiroshima Mayor Hamai Shinzō at a dedication of a commemorative stone lantern in Minamimachi on October 1, 1949. Honoring the Houses for Hiroshima project, the lantern bears the English message “That There May Be Peace.” (Courtesy Tomiko Y. Schmoe/Shumō ni Manabu Kai)

The lantern stands near the Heiwa Jūtaku municipal housing project, built at the same time as the Houses for Hiroshima. (© Dōune Hiroko)

Among the artifacts that Nishimura and others discovered in their research was a picture of a sign declaring the “Houses for Hiroshima” Work Camp Project. The photo shows Schmoe and a colleague hanging the board at a construction site, on which is written in Japanese and English the slogan of the project:

- To build understanding—

- By building houses—

- That there may be peace

According to accounts, the building sites drew locals, particularly children, who were intrigued by the sight of young foreigners and Japanese working side by side.

Nishimura notes that today, the war in Ukraine has resurrected in people’s minds the specter of nuclear war. “There is growing concern,” she says. “I’ve seen this volunteering at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Visitors are gradually realizing what Hiroshima and Nagasaki truly represent.” However, she does not want the focus to be on the scars inflicted by the bombing. “I want people to see Hiroshima as a symbol of renewal and peace building, and to pass this message on to the younger generation.” She regards the Schmoe House as an embodiment of this message. “It’s so small that one could easily walk by without even noticing it. But it is a poignant monument to the power of hope.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Volunteers post a sign showing the slogan of the Houses for Hiroshima project outside a site. Donated by Jean Walkinshaw; courtesy Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.)