Drifting Toward Defeat: Balloon Bombs and Youth Labor in Wartime Japan

History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Using the Jet Stream to Fly Bombs Across the Pacific

In early spring 1944 at the Ichinomiya Beach in Chiba Prefecture, 16-year old Ogawa Tatsuo (now 97) was helping launch experimental “balloon bombs” with other youths his age.

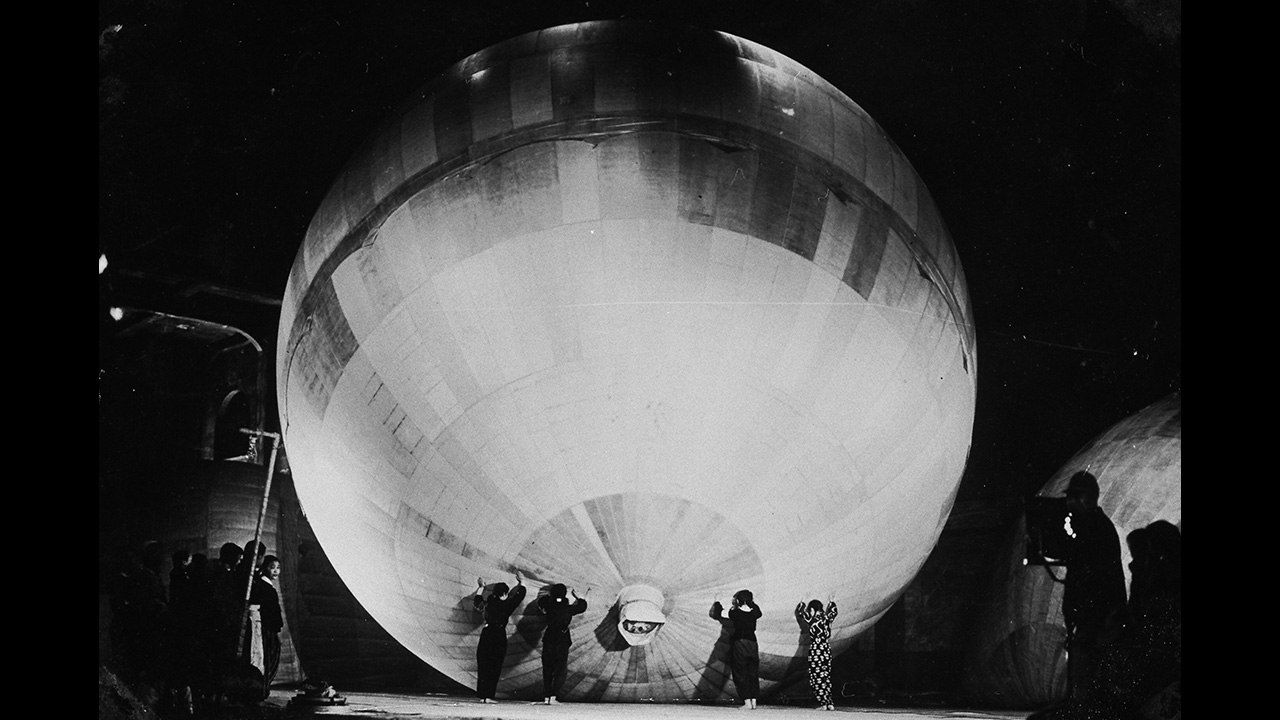

Six boys would inflate each paper balloon, inspect it for leaks, and release it into the sky. The giant balloons soared upward, as if being swallowed by the blue sky, and once they caught the jet stream, they would drift eastward toward the Pacific. The boys would gaze upward until the balloons vanished from sight.

“We knew that they were balloon bombs,” Ogawa recalls. “But we’d whisper to each other, ‘You really think we can beat America with this?’”

These paper balloons, given the codename Fu-Gō, were aerial weapons developed at the Imperial Japanese Army’s Ninth Technical Research Institute, also known as the Noborito Institute.

Improvements were made to the paper balloons used previously by the army by reinforcing handmade washi paper with layers of konjac paste. This made it possible to create large balloons measuring around 10 meters in diameter that were durable enough to survive the trans-Pacific journey. Multiple studies by the army’s Meteorological Department revealed that the balloons could reach North America in about two days if released in November, when jet stream speeds were at their peak.

The army packed them with explosives and began test launches at Ichinomiya Beach between February and March of 1944. Ogawa was among the boys who were mobilized to assist in these launches.

“No Way We Can Win with These Things”

The Noborito Institute also researched and manufactured radio and chemical weapons. More than 600 local residents worked there as support staff. Ogawa joined as a lathe operator after graduating from middle school.

One day, he was told to go to Ichinomiya Beach for a “special assignment”—the balloon bomb test flights.

“Six sturdy boys around my age were called. Our job was to carry the balloons to the beach and inflate them with hydrogen gas.”

Ogawa Tatsuo at his Kawasaki home. (© Hamada Nami)

Each balloon required 50 hydrogen cylinders—about 300 cubic meters of gas—and several hours to fill. Only four or five balloons could be launched per day. The boys also checked for holes on the balloon surface. “We climbed ladders and carefully inspected the whole thing from top to bottom,” Ogawa remembers, adding fondly, “We’d get a sweet potato for each hole we found, so that was a great incentive.”

The balloons carried radiosondes that transmitted signals during the flight. These were monitored by a tracking team to determine the balloons’ location and status. Sometimes the signals showed the balloons had fallen into the sea. Other times, the signals simply disappeared.

One day, a military official came to Ichinomiya with news that a balloon had reached the US mainland. Everyone involved was called to an inn and told, “Good work. The balloon bomb is our only weapon capable of striking America directly.” The adults toasted the achievement, but the boys returned to their room laughing, saying, “There’s no way we can win with these things.” Their team leader, older than the rest, slipped away from the party, saying flatly, “Japan’s gonna lose.” He wandered into town alone and never returned that night.

It was in November 1944, about six months after Ogawa returned to Kawasaki, that the army officially launched Operation Fu-Gō.

A sign describing the balloon bombs stands in a corner of a park slightly inland from the actual launch site. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

The Girls Erased from History

The balloon bombs used for Operation Fu-Gō were handmade by girls. After the Women’s Volunteer Labor Order was enacted in August 1944, unmarried females aged 12 and up were summoned to places like Tokyo’s Takarazuka Theater and Yūrakuza and given orders to assemble giant paper balloons. The military police warned them that this work was a top military secret and that they must never speak of it to anyone.

Unaware of what they were building, the girls labored in silence, and many passed away without ever revealing their role.

But their stories were brought back to life in the 2024 novel The Paper Balloon Bomb Follies by artist and writer Kobayashi Erika.

The book focuses on how these schoolgirls were pulled from a peaceful childhood and swept into war, exploring what each experienced and endured.

One scene describes the activities of the girls summoned to the Takarazuka Theater as follows:

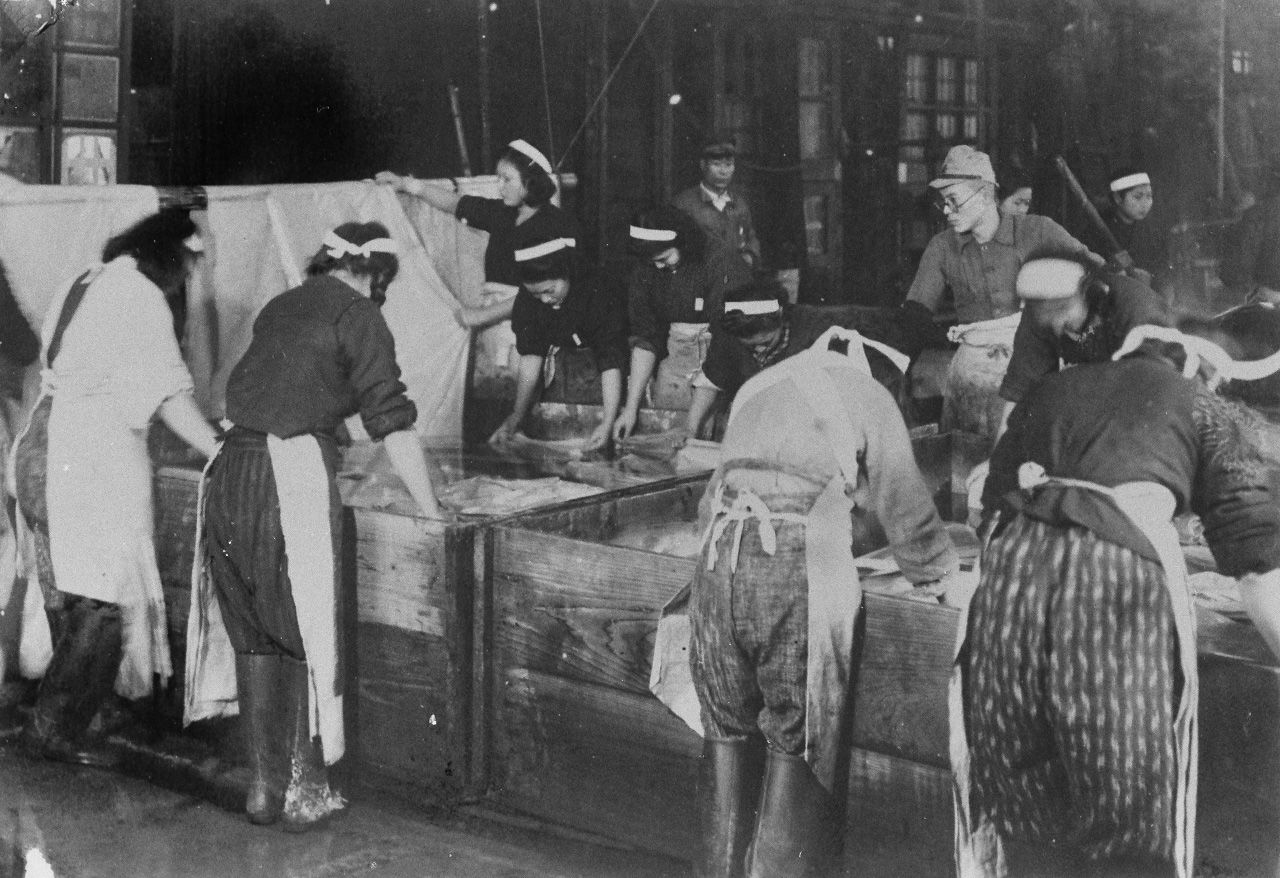

Sitting in a seiza posture on a cushion, I glue the cut pieces of washi paper together. . . . I scoop konjac paste from a wooden measuring box with my fingers. It feels cool even in summer. Mixing it with blue pigment makes it pale and semi-translucent. We apply it to the overlapping edges of the paper. Joining just three fragments of paper together formed trapezoids about the size of a tatami mat.

Kobayashi struggled to find materials on the Noborito Institute because of postwar efforts to destroy evidence. But through persistent outreach to schools like Futaba Junior and Senior High School where the girls studied, she happened upon unexpected documents.

“There were notes from roundtable discussions, a collection of essays compiled by retiring teachers, even scraps of paper with handwritten memos. Many of these included the names of students. The schools had preserved them as important records, and they entrusted the documents—along with the unspoken memory they contained—to me. It was a miracle.”

Female workers rinsing “balloon paper” after immersing it in caustic soda. (Thought to have been photographed by a contracted army cameraman at Kokura Arsenal. Courtesy of Meiji University’s Noborito Laboratory Museum for Education in Peace.)

Kobayashi also interviewed Minamimura Rei, a Futaba graduate who self-published her experiences of making the balloons. After the war, Minamimura married and was busy raising children. But one day she spotted a photograph in a bookstore window—an image just like the balloons she had helped assemble. Only then did she realize what she had been making. The shock was profound.

Minamimura personally visited the Defense Agency (now Ministry of Defense) to request materials and gather testimonies. She compiled these into a book that was published in 2000. When Kobayashi asked what had driven her to action, Minamimura replied:

“It was an act of resistance against being erased for so long.”

This made a strong impression on Kobayashi. “After hearing the word ‘resistance,’ I felt I had to continue the work of ensuring that no one else’s story would be erased from history.”

The novel’s success has transformed Meiji University’s Noborito Laboratory Museum for Education in Peace in Kawasaki. There has been a surge in visitors to the balloon bomb exhibit, especially women, many of whom leave comments like “I felt this was about me.”

Emperor’s Surrender Broadcast Came as No Surprise

Hoping to turn the tide of war with Operation Fu-Gō, the army launched some 9,300 balloons toward the United States. Only about 1,000 made landfall, though, and the only fatalities were seven members of a pastor’s family who encountered an unexploded bomb during a picnic. The operation was terminated in April 1945, after the US forces landed on Okinawa.

On the morning of August 15, the Noborito Institute received orders to destroy evidence. Ogawa was called to help in burning documents and burying the ashes. “We incinerated counterfeit bills—secretly printed in Noborito—that were sent back from Kobe Port days earlier. Some people gleefully picked up fragments of the charred bills.”

He heard the Emperor’s surrender broadcast in a vegetable patch in front of his home. The audio was distorted and hard to understand, but even as the adults around him wept, he was not surprised.

“Ater seeing the kind of bombers America had, it was obvious even to a kid that you can’t win with balloons. War is something we should never do again.”

Ichinomiya Beach, where the balloon bombs were launched, is now a popular destination for surfers. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

(Originally published in Japanese. Research and interviews by Power News. Banner photo: Female workers checking for flaws or leaks in the balloon bomb seams. Thought to have been photographed by a contracted army cameraman at Kokura Arsenal. Courtesy of Meiji University’s Noborito Laboratory Museum for Education in Peace.)