Building Blocks: The Basic Ingredients Behind Japan’s Flavors

Satsumaimo: From Food Shortage Essential to Sweet Treat

Food and Drink Culture Food and Drink- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Satsumaimo, or sweet potatoes, are native to Central and South America. They were introduced from China around the year 1600 into the Ryūkyū Kingdom (now Okinawa Prefecture), and from 1700 onward, they were cultivated in the province of Satsuma (now Kagoshima Prefecture), before spreading throughout Japan. In Kyūshū, they are often called karaimo, indicating their provenance from China (kara); in some areas, they are also known as kansho, the Japanese reading of the Chinese characters 甘薯, “sweet potato.”

Kagoshima and Ibaraki Prefectures are the top two production areas, each accounting for 30% of the total. However, in Kagoshima, they are mainly processed into other products, with 50% used as an ingredient for shōchū and 20% to produce starch. The satsumaimo widely available as fresh produce are mainly from Ibaraki Prefecture. Storing and maturing them after harvesting increases their sweetness. The various varieties of satsumaimo are usually ready for distribution in autumn and winter.

Digging for satsumaimo in autumn is a popular pastime. (Courtesy Ibaraki prefectural government)

Even when satsumaimo are grown in relatively poor soil, they still remain highly nutritious. This was noticed by Aoki Kon’yō (1698–1769), a scholar of rangaku (Western learning, which entered Japan via Dutch-language materials) in the Edo period. When the Kyōhō famine occurred in 1732, he wrote Banshokō, a treatise on satsumaimo, recommending their cultivation, which he submitted to the shogunate. He was ordered by the eighth shōgun Tokugawa Yoshimune to conduct trial cultivation and achieved results on the second try. The harvest from that successful trial was distributed as seed potatoes throughout Japan, and Kon’yō’s efforts led to him becoming widely revered as the “Sweet Potato Professor.” His work would pay off long into the future: Even during the food shortages in World War II, many people were saved from starvation by this humble tuber.

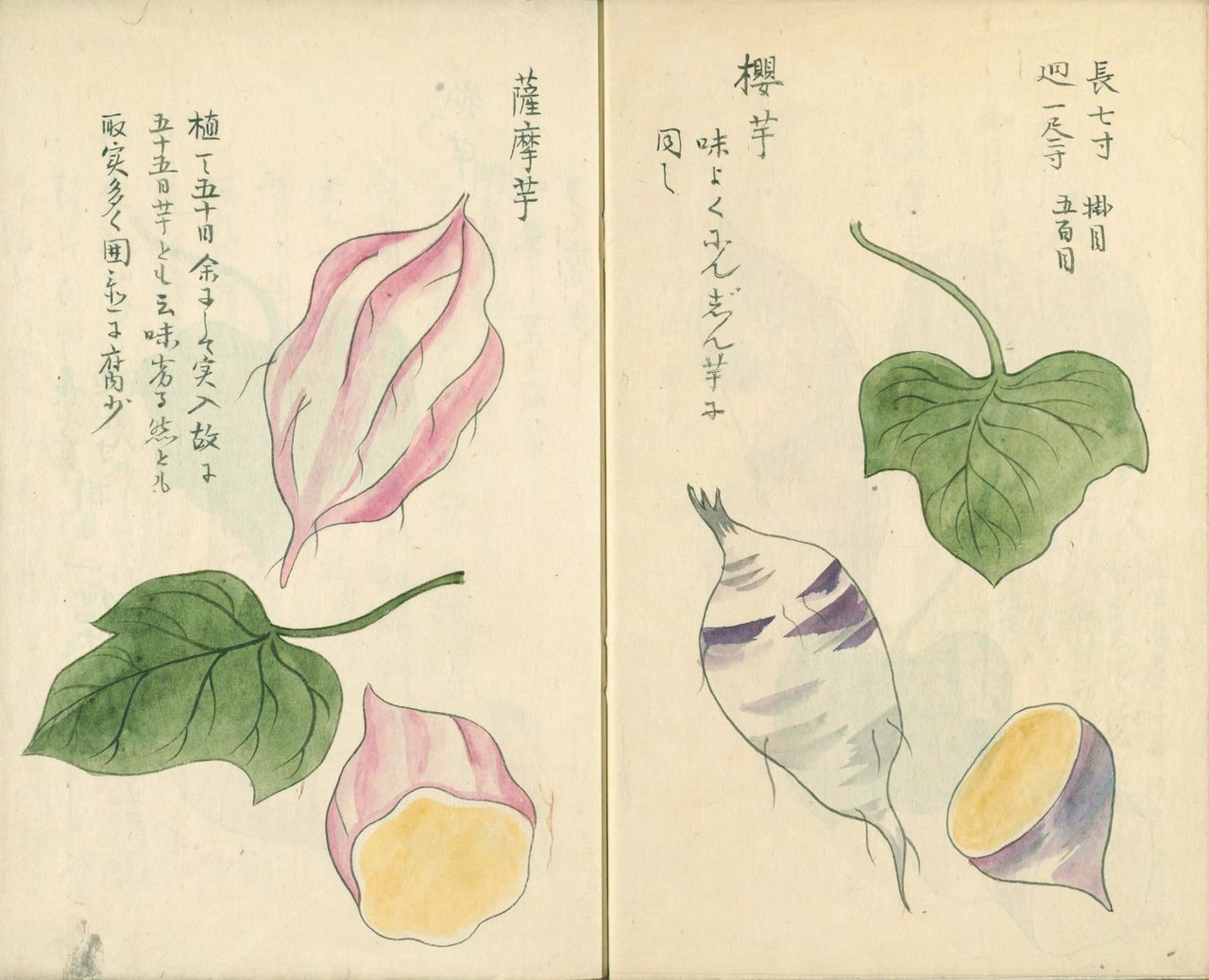

Illustrations of satsumaimo by Aoki Kon’yō. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Sticky, Sweet Annō Imo Revives the Yakiimo Boom

Rich in dietary fiber and vitamins, the most popular way to enjoy satsumaimo is roasting them to eat as a snack. The yakiimo vendors that began trading in the Edo period (1603–1868) changed their business model after World War II and began travelling around towns selling them from carts or trucks. Satsumaimo slowly roasted on hot stones are particularly delicious.

(Courtesy Ibaraki prefectural government)

The hot, fluffy Beniazuma became the established variety for yakiimo, but then in the 2000s the sticky, sweet Annō Imo, originating from the Kagoshima island of Tanegashima, sparked a new boom. Moreover, the development of electric automatic yakiimo roasters meant freshly baked sweet potatoes could be bought at supermarkets, further propelling their popularity as a healthy snack.

In the 2010s, new varieties like the candy-sweet Beniazuma and Silk Sweet, praised for its silky smoothness and moist texture, gained attention, boosting the yakiimo market further. Japan’s unique varieties are also highly regarded overseas and, over the last 10 years, export values have increased 9.4-fold, with the market thriving especially in Asia.

(Originally published in Japanese. Text by Ecraft. Banner photo courtesy Ibaraki prefectural government.)